User:Wassupwestcoast/sandbox

Genetic changes between generations either increase or decrease the chance of an organism's survival. |

| Overview |

| Life forms reproduce to make offspring. |

| The offspring differs from the parent in minor random ways. |

| If the differences are helpful, the offspring is more likely to survive and reproduce. |

| This means that more offspring in the next generation will have the helpful difference. |

| These differences accumulate resulting in changes within the population. |

| Over time, this process gradually leads to entirely new types of life. |

| This process is responsible for the many diverse life forms in the world today. |

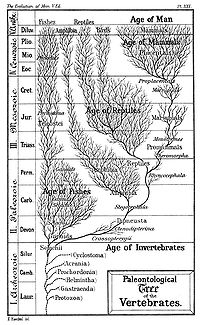

The evolutionary history of species has been described as a "tree", with many branches arising from a single trunk. While Haeckel's tree is somewhat outdated, it illustrates clearly the principles that more complex modern reconstructions can obscure. |

Evolution is the natural process by which all life changes over generations. Individual organisms inherit their particular characteristics (their traits) from their parents through genes. Changes (called mutations) in these genes can become a new trait in the offspring of an organism. If a new trait makes these offspring better suited to their environment, they will be more successful at surviving and reproducing. This process is called natural selection and causes favorable traits to become more common. Over many generations, a group of individuals in a population can accumulate so many new traits that it becomes a new species.[1][2]

Evolutionary biology is the study of evolution, especially the natural processes that account for the variety of organisms, both alive today and long extinct. The understanding of evolutionary biology began with the 1859 publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species. In addition, Gregor Mendel's work with plants helped to explain the hereditary patterns of genetics. This led to an understanding of the mechanisms of inheritance.[3] Further discoveries on how genes mutate, as well as advances in population genetics explained more details of how evolution occurs. Scientists now have a good understanding of the origin of new species (speciation). They have observed the speciation process happening both in the laboratory and in the wild. This modern view of evolution is the principal theory that scientists use to understand life.

Darwin's idea: evolution by natural selection

Patterns in the geographical distribution of species and their fossil predecessors convinced Charles Darwin that each had developed from similar ancestors, and in 1838, he formulated an explanation known as natural selection.[4] Darwin's explanation of the mechanism of evolution relied on his theory of natural selection, a theory developed from the following observations:[5]

- 1. If all the individuals of a species reproduced successfully, the population of that species would increase exponentially.

- 2. Except for seasonal changes, populations tend to remain stable in size.

- 3. Environmental resources are limited.

- 4. The traits found in a population vary greatly. No two individuals in a given species are exactly alike.

- 5. Many of the variations found in a population can be passed on to offspring.

Darwin deduced that the production of more offspring than the environment could support led inevitably to a struggle for existence. Only a small proportion of individuals could survive in each generation. Darwin realized that it was not chance that determined survival of any individual. Survival depended on the traits of each individual and whether a particular trait was a benefit or a hindrance to the survival and the reproductive success in a particular environment. Well-adapted, or "fit", individuals were likely to leave a greater number of offspring than their less well-adapted competitors. Darwin concluded that the unequal ability of individuals to survive and reproduce led to gradual changes in the population. Traits which helped the organism survive and reproduce would accumulate over the generations. Traits that inhibit survival and reproduction would be lost. Darwin used the term natural selection to describe this process.[6]

Observations of variations in animals and plants formed the basis of the theory of natural selection. For example, Darwin observed that orchids and insects have a close relationship which ensures successful pollination of the plants. He noted that orchids had developed a variety of elaborate structures to attract insects so that pollen from the flowers gets stuck to the insects’ bodies. In this way, insects transport the pollen to a female orchid. In spite of the elaborate appearance of the orchid its specialized parts evolved from the same basic structures as other flowers. Darwin proposed that the orchid flowers did not represent the work of an ideal engineer, but were adapted from pre-existing parts through natural selection.[7]

Darwin was still researching and experimenting with his ideas on natural selection when he received a letter from Alfred Wallace enclosing the manuscript of a theory that was essentially the same as his own which led to an immediate joint publication of both theories. Both Wallace and Darwin saw the history of life as resembling a tree structure, each fork in the tree’s limbs representing a shared ancestry. The tips of the limbs represented modern species and the branches represented the common ancestors shared amongst species. To explain these relationships, Darwin said that all living things were related, and this meant that all life must be descended from a few forms, or even from a single common ancestor. He called this process "descent with modification".[5]

Darwin published his theory of evolution by natural selection in On the Origin of Species in 1859. His theory means that all life, including humanity, is a product of continuing natural processes. The implication that all life on earth has a common ancestor has met with religious objections, and people who believe that the different types of life are due to special creation regard it as a controversy.[8] Their objections are in contrast to the level of support for the theory by more than 99 percent of those within the scientific community today.[9]

Source of variation

Darwin’s theory of natural selection laid the groundwork for modern evolutionary theory, and his experiments and observations showed that heritable variations occurred within populations and were controlled by natural selection. However, he lacked an explanation for the source of these variations. Like many of his predecessors, Darwin mistakenly thought that heritable traits were a product of use and disuse, and that characteristics acquired during an organism's lifetime could be passed on to its offspring. He looked for examples, such as large ground feeding birds getting stronger legs and weaker wings until, like the ostrich, they could no longer fly.[10] This misconception, called the inheritance of acquired characters, had been part of the theory of transmutation of species put forward in 1809 by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. In the late 19th century the theory became known as Lamarckism. Darwin produced an unsuccessful theory he called pangenesis to try to explain how acquired characteristics could be inherited. In the 1880s August Weismann's experiments indicated that changes from use and disuse were not heritable, and Lamarckism gradually fell from favour.[11]

The missing information necessary to help explain the emergence of new traits in offspring was provided by the pioneering genetics work of Gregor Mendel. Mendel’s experiments with several generations of pea plants demonstrated that heredity works by reshuffling the hereditary information during the formation of sex cells and recombining that information during fertilization. Mendel referred to the information as factors; however, they later became known as genes. Genes are the basic units of heredity in living organisms. They contain the biological information that directs the physical development and behavior of organisms.

Genes are composed of DNA, a long molecule that has the form of a "double helix". It resembles a ladder that has been twisted. The rungs of the ladder are formed by chemicals called nucleotides. There are four types of nucleotides, and the sequence of nucleotides carries the information in the DNA. There are short segments of the DNA called genes. The genes are like sentences built up of the "letters" of the nucleotide alphabet. Chromosomes are packages for carrying the DNA in the cells. Later research by Thomas Hunt Morgan showed that genes are linked in a series on chromosomes and it is the reshuffling of these chromosomes that results in unique combinations in offspring.

In 1953, biologist James Watson and chemist Francis Crick contributed to one of the most important breakthroughs in biological science: they discovered the chemical nature of variations within populations. Their work demonstrated how the chemical deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) could serve as the hereditary code. They explained the chemistry of genes and the role that chemistry plays in evolution: genetic variations in a population arise by chance mutations in DNA. Although such mutations are random, natural selection is not a process of chance: the environment determines the probability of reproductive success. The end products of natural selection are organisms that are adapted to their present environments.

Natural selection does not involve progress towards an ultimate goal. Evolution does not necessarily strive for more advanced, more intelligent, or more sophisticated life forms.[12] For example, fleas (wingless parasites) are descended from a winged, ancestral scorpionfly,[13] and snakes are lizards that no longer require limbs. Organisms are merely the outcome of variations that succeed or fail, dependent upon the environmental conditions at the time. Environmental changes that occur over short periods typically lead to extinction.[12] Of all species that have existed on Earth, 99.9 percent are now extinct.[14] Since life began on Earth, five major mass extinctions have lead to significant reduction in species diversity. The most recent, the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event, occurred 65 million years ago, and has attracted more attention than all others because it killed the dinosaurs.[15]

Modern synthesis

The modern evolutionary synthesis was the outcome of a merger of several different scientific fields into a cohesive understanding of evolutionary theory. In the 1930s and 1940s, efforts were made to merge Darwin's theory of natural selection, research in heredity, and understandings of the fossil records into a unified explanatory model.[16] The application of the principles of genetics to naturally occurring populations by scientists such as Theodosius Dobzhansky and Ernst Mayr advanced understanding of the processes of evolution. Dobzhansky's 1937 work Genetics and the Origin of Species was an important step in bridging the gap between genetics and field biology. Mayr, on the basis of an understanding of genes and direct observations of evolutionary processes from field research, introduced the biological species concept, which defined a species as a group of interbreeding or potentially interbreeding populations that are reproductively isolated from all other populations. The paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson helped to incorporate fossil research which showed a pattern consistent with the branching and non-directional pathway of evolution of organisms predicted by the modern synthesis. The modern synthesis emphasizes the importance of populations as the unit of evolution, the central role of natural selection as the most important mechanism of evolution, and the idea of gradualism to explain how large changes evolve as an accumulation of small changes over long periods of time.

Evidence for evolution

Scientific evidence for evolution comes from many aspects of biology, and includes fossils, homologous structures, and molecular similarities between species' DNA.

Fossil record

Research in the field of paleontology, the study of fossils, supports the idea that all living organisms are related. Fossils provide evidence that accumulated changes in organisms over long periods of time have led to the diverse forms of life we see today. A fossil itself reveals the organism's structure and the relationships between present and extinct species, allowing paleontologists to construct a family tree for all of the life forms on earth.[17]

Modern paleontology began with the work of Georges Cuvier (1769–1832). Cuvier noted that, in sedimentary rock, each layer contained a specific group of fossils. The deeper layers, which he proposed to be older, contained simpler life forms. He noted that many forms of life from the past are no longer present today. One of Cuvier’s successful contributions to the understanding of the fossil record was establishing extinction as a fact. In an attempt to explain extinction, Cuvier proposed the idea of “revolutions” or catastrophism in which he speculated that geological catastrophes had occurred throughout the earth’s history, wiping out large numbers of species.[18] Cuvier's theory of revolutions was later replaced by uniformitarian theories, notably those of James Hutton and Charles Lyell who proposed that the earth’s geological changes were gradual and consistent.[19] However, current evidence in the fossil record supports the concept of mass extinctions. As a result, the general idea of catastrophism has re-emerged as a valid hypothesis for at least some of the rapid changes in life forms that appear in the fossil records.

A very large number of fossils have now been discovered and identified. These fossils serve as a chronological record of evolution. The fossil record provides examples of transitional species that demonstrate ancestral links between past and present life forms.[20]

One such transitional fossil is Archaeopteryx, an ancient organism that had the distinct characteristics of a reptile, yet had the feathers of a bird. The implication from such a find is that modern reptiles and birds arose from a common ancestor.[21][22]

Comparative anatomy

The comparison of similarities between organisms of their form or appearance of parts, called their morphology, has long been a way to classify life into closely related groups. This can be done by comparing the structure of adult organisms in different species or by comparing the patterns of how cells grow, divide and even migrate during an organism's development.

- Taxonomy

Taxonomy is the branch of biology that names and classifies all living things. Scientists use morphological and genetic similarities to assist them in categorizing life forms based on ancestral relationships. For example, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans all belong to the same taxonomic grouping referred to as a family – in this case the family called Hominidae. These animals are grouped together because of similarities in morphology that come from common ancestry (called homology).[23]

Strong evidence for evolution comes from the analysis of homologous structures in different species that no longer perform the same task.[24] Such is the case of the forelimbs of mammals. The forelimbs of a human, cat, whale, and bat all have strikingly similar bone structures. However, each of these four species' forelimbs performs a different task. The same bones that construct a bird's wings, which are used for flight, also construct a whale's flippers, which are used for swimming. Such a "design" makes little sense if they are unrelated and uniquely constructed for their particular tasks. The theory of evolution explains these homologous structures: all four animals shared a common ancestor, and each has undergone change over many generations. These changes in structure have produced forelimbs adapted for different tasks. Darwin described such changes in morphology as descent with modification.[25]

- Embryology

In some cases, anatomical comparison of structures in the embryos of two or more species provides evidence for a shared ancestor that may not be obvious in the adult forms. As the embryo develops, these homologies can be lost to view, and the structures can take on different functions. Part of the basis of classifying the vertebrate group (which includes humans), is the presence of a tail (extending beyond the anus) and pharyngeal gill slits. Both structures appear during some stage of embryonic development but are not always obvious in the adult form.[26]

Because of the morphological similarities present in embryos of different species during development, it was once assumed that organisms re-enact their evolutionary history as an embryo. It was thought that human embryos passed through an amphibian then a reptilian stage before completing their development as mammals. Such a re-enactment, called ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, is not supported by scientific evidence. What does occur, however, is that the first stages of development are similar in broad groups of organisms.[27] At the pharyngula stage, for instance, all vertebrates are extremely similar, but do not exactly resemble any ancestral species. As development continues, the features specific to the species emerge from the basic pattern.

- Vestigial structures

Homology includes a unique group of shared structures referred to as vestigial structures. Vestigial refers to anatomical parts that are of minimal, if any, value to the organism that possesses them. These apparently illogical structures are remnants of organs that played an important role in ancestral forms. Such is the case in whales, which have small vestigial bones that appear to be remnants of the leg bones of their ancestors which walked on land.[28] Humans also have vestigial structures, including the ear muscles, the wisdom teeth, the appendix, the tail bone, body hair (including goose bumps), and the semilunar fold in the corner of the eye.[29]

- Convergent evolution

Anatomical comparisons can be misleading, as not all anatomical similarities indicate a close relationship. Organisms that share similar environments will often develop similar physical features in a process known as convergent evolution. Both sharks and dolphins have similar body forms, yet are only distantly related – sharks are fish and dolphins are mammals. Such similarities are a result of both populations being exposed to the same selective pressures. Within both groups, changes that aid swimming have been favored. Thus, over time, they developed similar morphology, even though they are not closely related.[30]

Artificial selection

Artificial selection is the controlled breeding of domestic plants and animals. In controlled breeding, humans determine which animals will reproduce and thus, to some degree, which genes will be passed on to future generations. The process of artificial selection has had a significant impact on the evolution of domestic animals. For example, people have produced different types of dogs by controlled breeding. The differences in size between the Chihuahua and the Great Dane are the result of artificial selection. Despite their dramatically different physical appearance, they and all other dogs evolved from a few wolves domesticated by humans in what is now China less than 15,000 years ago.[31]

Artificial selection has produced a wide variety of plants. In the case of maize (corn), recent genetic evidence suggests that domestication occurred 10,000 years ago in central Mexico.[32] Prior to domestication, the edible portion of the wild form was small and difficult to collect. Today The Maize Genetics Cooperation • Stock Center maintains a collection of more than 10,000 genetic variations of maize that have arisen by random mutations and chromosomal variations from the original wild type.[33]

Darwin drew much of his support for natural selection from observing the outcomes of artificial selection.[34] Much of his book On the Origin of Species was based on his observations of the diversity in domestic pigeons arising from artificial selection. Darwin proposed that if dramatic changes in domestic plants and animals could be achieved by humans in short periods, then natural selection, given millions of years, could produce the differences between living things today. There is no real difference in the genetic processes underlying artificial and natural selection. As in natural selection, the variations are a result of random mutations; the only difference is that in artificial selection, humans select which organisms will be allowed to breed.[24]

Molecular biology

Every living organism contains molecules of DNA, which carries genetic information. Genes are the pieces of DNA that carry this information and they influence the properties of an organism. Genes determine a person's general appearance and to some extent their behavior. Since close relatives have similar genes they tend to look alike. The exact form of the genes in an organism is called the organism's genotype and this set of genes influences the properties (or phenotype) of an organism.[35]

If two organisms are closely related, their DNA will be very similar.[36] On the other hand, the more distantly-related two organisms are, the more differences they will have. For example, two brothers will be very closely related and will have very similar DNA, while distant cousins will have far more differences between their DNA. As well as showing how closely-related two individuals are, DNA can show how closely-related two species are. For example, comparing chimpanzees with gorillas and humans shows that there is as much as a 96 percent similarity between the DNA of humans and chimps, and that humans and chimpanzees are more closely related to each other than either species are to gorillas.[37][38]

The field of molecular systematics focuses on measuring the similarities in these molecules and using this information to work out how different types of organisms are related through evolution. These comparisons have allowed biologists to build a relationship tree of the evolution of life on earth.[39] They have even allowed scientists to unravel the relationships of organisms whose common ancestors lived such a long time ago that no real similarities remain in the appearance of the organisms.

Co-evolution

Co-evolution is a process in which two or more species influence the evolution of each other. All organisms are influenced by life around them; however, in co-evolution there is evidence that genetically determined traits in each species directly resulted from the interaction between the two organisms.[36]

An extensively documented case of co-evolution is the relationship between Pseudomyrmex, a type of ant, and the acacia, a plant that the ant uses for food and shelter. The relationship between the two is so intimate that it has led to the evolution of special structures and behaviors in both organisms. The ant defends the acacia against herbivores and clears the forest floor of the seeds from competing plants. In response, the plant has evolved swollen thorns that the ants use as shelter and special flower parts that the ants eat.[40] Such co-evolution does not imply that the ants and the tree choose to behave in an altruistic manner. Rather, across a population small genetic changes in both ant and tree benefited each and the benefit gave a slightly higher chance of the characteristic being passed on to the next generation. Over time, successive mutations created the relationship we observe today.

Species

Given the right circumstances, and enough time, evolution leads to the emergence of new species. Scientists have struggled to find a precise and all-inclusive definition of species. Ernst Mayr (1904–2005) defined a species as a population or group of populations whose members have the potential to interbreed naturally with one another to produce viable, fertile offspring. (The members of a species cannot produce viable, fertile offspring with members of other species.)[25] Mayr's definition has gained wide acceptance among biologists, but does not apply to organisms such as bacteria, which reproduce asexually.

Speciation is the lineage-splitting event that results in two separate species forming from a single common ancestral population.[6] A widely accepted method of speciation is called allopatric speciation. Allopatric speciation begins when a population becomes geographically separated.[24] Geological processes, such as the emergence of mountain ranges, the formation of canyons, or the flooding of land bridges by changes in sea level may result in separate populations. For speciation to occur, separation must be substantial, so that genetic exchange between the two populations is completely disrupted. In their separate environments, the genetically isolated groups follow their own unique evolutionary pathways. Each group will accumulate different mutations as well as be subjected to different selective pressures. The accumulated genetic changes may result in separated populations that can no longer interbreed if they are reunited.[6] Barriers that prevent interbreeding are either prezygotic (prevent mating or fertilization) or postzygotic (barriers that occur after fertilization). If interbreeding is no longer possible, then they will be considered different species.[41]

Usually the process of speciation is slow, occurring over very long time spans; thus direct observations within human life-spans are rare. However speciation has been observed in present day organisms, and past speciation events are recorded in fossils.[42][43][44] Scientists have documented the formation of five new species of cichlid fishes from a single common ancestor that was isolated fewer than 4000 years ago from the parent stock in Lake Nagubago. The evidence for speciation in this case was morphology (physical appearance) and lack of natural interbreeding. These fish have complex mating rituals and a variety of colorations; the slight modifications introduced in the new species have changed the mate selection process and the five forms that arose could not be convinced to interbreed.[45]

Barriers to breeding between species

Reproductive barriers that prevent interbreeding can be classified as either prezygotic barriers or postzygotic barriers.[46] The distinction between the two lies in whether the barrier prevents the generation of offspring before fertilization of the egg or following such fertilization.

Barriers that prevent fertilization

Prezygotic barriers are those barriers which prevent mating between species or prevent the fertilization of the egg if the species attempt to mate.[24]

Some examples are:

- Temporal isolation – Occurs when species mate at different times. Populations of the western spotted skunk (Spilogale gracilis) overlap with the eastern spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius) yet remain separate species because the former mates in summer and the latter in late winter.[46]

- Behavioral isolation – Signals that elicit a mating response may be sufficiently different to prevent a desire to interbreed. The rhythmic flashing in male fireflies is species-specific and thus serves as a prezygotic barrier.[47]

- Mechanical isolation – Anatomical differences in reproductive structures may prevent interbreeding. This is especially true in flowering plants that have evolved specific structures adapted to certain pollinators. Nectar-feeding bats searching for flowers are guided by their echolocation system. Therefore, plants which depend on these bats as pollinators have evolved acoustically conspicuous flowers that assist in detection.[48]

- Gametic isolation – The gametes of the two species are chemically incompatible, thus preventing fertilization. Gamete recognition may be based on specific molecules on the surface of the egg that attach only to complementary molecules on the sperm.[46]

- Geographic/habitat isolation – Geographic: The two species are separated by large-scale physical barriers, such as a mountain, large body of water, or physical barriers constructed by humans. Such barriers disrupt gene flow between the isolated groups. This is illustrated in the divergence of plant species on opposite sides of the Great Wall of China.[49] Habitat: The two species prefer different habitats, even if they live in the same general area, and therefore do not encounter each other. For example, in the Rhagoletis flies their original, host plants are hawthorn trees. Apple trees were introduced into their habitat more than 300 years ago. Now, some flies use apple trees instead of hawthorns as their host plants. Studies show that flies have a strong genetic preference for the tree (apple or hawthorn) on which they were found, and that mating takes place on the host plant. Even though these two populations are found in the same areas, their ecological isolation has been sufficient and genetic divergence has occurred.[46]

Barriers acting after fertilization

Postzygotic barriers are those barriers that occur after fertilization, usually resulting in the formation of a hybrid zygote that is either not viable or not fertile. This is typically a result of incompatible chromosomes in the zygote. A zygote is a fertilized egg before it divides, or the organism that results from this fertilized egg. Viable means something is capable of life or normal growth and development[24]

Examples include:

- Reduced hybrid viability – A barrier between species occurs after the formation of the zygote, resulting in incomplete development and death of the offspring.[50]

- Reduced hybrid fertility – Even if two different species successfully mate, the offspring produced may be infertile. Crosses of horse species within the genus Equus tend to produce viable but sterile offspring. For example, crosses of zebra x horse and zebra x donkey produce sterile zorses and zedonks. Horse x donkey crosses produce sterile mules. Very rarely, a female mule may be fertile.[51]

- Hybrid breakdown – Some hybrids are fertile for a single generation but then become weak or inviable.[52]

Different views on the mechanism of evolution

The theory of evolution is widely accepted among the scientific community, serving to link the diverse specialty areas of biology.[9] Evolution provides the field of biology with a solid scientific base. The significance of evolutionary theory is best described by the title of a paper by Theodosius Dobzhansky (1900–1975), published in American Biology Teacher; "Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution".[53] Nevertheless, the theory of evolution is not static. There is much discussion within the scientific community concerning the mechanisms behind the evolutionary process. For example, the rate at which evolution occurs is still under discussion. In addition, the primary unit of evolutionary change, the organism or the genes, is not agreed on.

Rate of change

Two views exist concerning the rate of evolutionary change. Darwin and his contemporaries viewed evolution as a slow and gradual process. Evolutionary trees are based on the idea that profound differences in species are the result of many small changes that accumulate over long periods.

The view that evolution is gradual had its basis in the works of the geologist James Hutton (1726–1797) and his theory called "gradualism". Hutton's theory suggests that profound geological change was the cumulative product of a relatively slow continuing operation of processes which can still be seen in operation today, as opposed to catastrophism which promoted the idea that sudden changes had causes which can no longer be seen at work. A uniformitarian perspective was adopted for biological changes. Such a view can seem to contradict the fossil record, which shows evidence of new species appearing suddenly, then persisting in that form for long periods. The paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould (1940–2002) developed a model that suggests that evolution, although a slow process in human terms, undergoes periods of relatively rapid change over only a few thousand or million years, alternating with long periods of relative stability, a model called "punctuated equilibrium" which explains the fossil record without contradicting Darwin's ideas.[54]

Unit of change

It is generally accepted amongst biologists that the unit of selection in evolution is the organism, and that natural selection serves to either enhance or reduce the reproductive potential of an individual. Reproductive success, therefore, can be measured by the volume of an organism's surviving offspring. The organism view has been challenged by a variety of biologists as well as philosophers. Richard Dawkins (born 1941) proposes that much insight can be gained if we look at evolution from the gene's point of view; that is, that natural selection operates as an evolutionary mechanism on genes as well as organisms.[55] In his book The Selfish Gene, he explains:

Individuals are not stable things, they are fleeting. Chromosomes too are shuffled to oblivion, like hands of cards soon after they are dealt. But the cards themselves survive the shuffling. The cards are the genes. The genes are not destroyed by crossing-over; they merely change partners and march on. Of course they march on. That is their business. They are the replicators and we are their survival machines. When we have served our purpose we are cast aside. But genes are denizens of geological time: genes are forever.[56]

Others view selection working on many levels, not just at a single level of organism or gene; for example, Stephen Jay Gould called for a hierarchical perspective on selection.[57]

Summary

| Evolution in popular culture |

| The language of evolution became pervasive in Victorian Britain as Darwin's work spread and became better known: |

| "Survival of the fittest" – used by Herbert Spencer in Principles of Biology (1864) |

| "Nature, red in tooth and claw" – from Alfred Lord Tennyson's In Memoriam A.H.H. (1849) While this poem preceded the publication of Darwin's work in 1859, it came to represent evolution for both evolution detractors and supporters. |

| It even merited a song in Gilbert and Sullivan's 1884 opera, Princess Ida, which concludes: "Darwinian man, though well behaved, |

Several basic observations establish the theory of evolution, which explains the variety and relationship of all living things. There are genetic variations within a population of individuals. Some individuals, by chance, have features that allow them to survive and thrive better than their kind. The individuals that survive will be more likely to have offspring of their own. The offspring might inherit the useful feature.

Evolution is not a random process for creating new life forms. While mutations are random, natural selection is not. Evolution is an inevitable result of imperfectly copying, self-replicating organisms reproducing over billions of years under the selective pressure of the environment. The result is not perfectly designed organisms. Rather, the result is individuals that can survive better than their nearest neighbor can in a particular environment. Fossils, the genetic code, and the peculiar distribution of life on earth, which demonstrates the common ancestry of all organisms, both living and long dead, provide a record of evolution. Selective breeding for certain traits by human beings is evolution and resulted in domestic animals and plants like cats and dogs, wheat and peas.

Although some groups raise objections to the theory of evolution, the evidence of observation and experiments over a hundred years by thousands of scientists supports evolution.[8] The result of four billion years of evolution is the diversity of life around us, with an estimated 1.75 million different species in existence today.[2][58]

See also

- Misconceptions about evolution

- Evidence of common descent

- Creation-evolution controversy

- Level of support for evolution

References

- ^ "An introduction to evolution", Understanding Evolution: your one-stop source for information on evolution (web resource), The University of California Museum of Paleontology, Berkeley, 2008, retrieved 2008-01-23

- ^ a b Cavalier-Smith T (2006). "Cell evolution and Earth history: stasis and revolution" (pdf). Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 361 (1470): 969–1006. PMID 16754610. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ^ Rhee, Sue Yon (1999). "Gregor Mendel". Access Excellence. National Health Museum. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ^ a b Eldredge, Niles (Spring 2006). "Confessions of a Darwinist". The Virginia Quarterly Review: 32–53. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ a b Wyhe, John van (2002). "Charles Darwin: gentleman naturalist". The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online. University of Cambridge. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Quammen, David (2004). "Was Darwin Wrong?". National Geographic Magazine. National Geographic. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ^ Wyhe, John van (2002). "Fertilisation of Orchids". The Complete Works of Charles Darwin. University of Cambridge. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ a b DeVries A (2004). "The enigma of Darwin". Clio Med. 19 (2): 136–155. PMID 6085987.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Delgado, Cynthia (2006). "Finding the Evolution in Medicine". NIH Record (National Institutes of Health). Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1872). "Effects of the increased Use and Disuse of Parts, as controlled by Natural Selection". The Origin of Species. 6th edition, p. 108. John Murray. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ^ Ghiselin, Michael T. (September/October 1994), "Nonsense in schoolbooks: 'The Imaginary Lamarck'", The Textbook Letter, The Textbook League, retrieved 2008-01-23

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|publication-date=(help) - ^ a b "Frequently Asked Questions About Evolution", Evolution Library, WGBH Educational Foundation, 2001, retrieved 2008-01-23

- ^ Hutchinson, Robert (1999). "Fleas". Veterinary Entomology. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ^ "Roundtable: Mass Extinction", Evolution: a jouney into where we're from and where we're going, WGBH Educational Foundation, 2001, retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ Bambach, R.K.; Knoll, A.H.; Wang, S.C. (December 2004), "Origination, extinction, and mass depletions of marine diversity", Paleobiology, 30 (4): 522–542, retrieved 2008-01-24

- ^ Committee on Defining and Advancing the Conceptual Basis of Biological Sciences (1989). "The tangled web of biological science". The role of theory in advancing 21st Century Biology:Catalyzing Transformation Research. National Research Council. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ "The Fossil Record - Life's Epic". The Virtual Fossil Museum. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- ^ Tattersall, Ian (1995). The Fossil Trail: How We Know What We Think We Know About Human Evolution. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195061012.

- ^ Secord, James A.; Lyell, Charles (1997). Principles of geology. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 014043528X. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Committee on Revising Science and Creationism: A View from the National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Sciences and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (2008). "Science, Evolution, and Creationism". National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (1995). Dinosaur in a Haystack. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 0517703939.

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (1981). The Panda's Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History. New York: W.W, Norton & Company. ISBN 0393308197.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (1992). The Third Chimpanzee: the evolution and future of the human animal. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0060183071.

- ^ a b c d e "Glossary", Evolution Library (web resource), WGBH Educational Foundation, 2001, retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ a b Mayr, Ernst (2001). What evolution is. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-04425-5.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Weichert &, Charles (1975). Elements of Chordate Anatomy. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0070690081.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Miller, Kenneth (1997). "Haeckel and his Embryos". Evolution Resources. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

- ^ Pagel, Mark (2002). Vestigial Organs and Structures. In Encyclopedia of Evolution. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195122003.

- ^ Johnson, George (2002), "Vestigial Structures", The Evidence for Evolution (web resource), 'On Science' column in St. Louis Post Dispatch, retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ Johnson, George (2002), "Convergent and Divergent Evolution", The Evidence for Evolution (web resource), 'On Science' column in St. Louis Post Dispatch, retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ McGourty, Christine (2002-11-22). "Origin of dogs traced". BBC News. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- ^ Hall, Hardy. "Transgene Escape: Are Traditioanl Corn Varieties In Mexico Threatened by Transgenic Corn Crops". Scientific Creative Quarterly. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- ^ "The Maize Genetics Cooperation • Stock Center". National Plant Germplasm. U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2006-06-21. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ^ Wilner A. (2006). "Darwin's artificial selection as an experiment". Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci. 37 (1): 26–40. PMID 16473266.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Graur, Dan (2000). Fundamentals of Molecular Evolution. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0878932666.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Kennedy, Donald (1998). "Teaching about evolution and the nature of science". Evolution and the nature of science. The National Academy of Science. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lovgren, Stefan (2005-08-31). "Chimps, Humans 96 Percent the Same, Gene Study Finds". National Geographic News. National Geographic. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Carroll SB, Grenier J, Weatherbee SD (2000). From DNA to Diversity: Molecular Genetics and the Evolution of Animal Design (2nd Edition ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-1950-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ciccarelli FD, Doerks T, von Mering C, Creevey CJ, Snel B, Bork P (2006). "Toward automatic reconstruction of a highly resolved tree of life". Science. 311 (5765): 1283–7. PMID 16513982.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Janzen, Daniel (1974). "Swollen-Thorn Acacias of Central America" (pdf). Smithsonian Contributions to Biology. Smithsonian Institute. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sulloway, Frank J (December 2005). "The Evolution of Charles Darwin". Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institute. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- ^ Jiggins CD, Bridle JR (2004). "Speciation in the apple maggot fly: a blend of vintages?". Trends Ecol. Evol. (Amst.). 19 (3): 111–4. PMID 16701238.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Boxhorn, John (1995). "Observed Instances of Speciation". The TalkOrigins Archive. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ Weinberg JR, Starczak VR, Jorg, D (1992). "Evidence for Rapid Speciation Following a Founder Event in the Laboratory". Evolution. 46 (4): 1214–20. doi:10.2307/2409766.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mayr, Ernst (1970). Populations, Species, and Evolution. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674690109.

- ^ a b c d Bright, Kerry (2006). "Causes of evolution". Teach Evolution and Make It Relevant. National Science Foundation. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ Cratsley, Christopher K (2004). "Flash Signals, Nuptial Gifts and Female Preference in Photinus Fireflies". Integrative and Comparative Biology. bNet Research Center. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ^ Helversen D, Holderied M, & Helversen O (2003). "Echoes of bat-pollinated bell-shaped flowers: conspicuous for nectar-feeding bats?". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 206 (1): 1025–1034. doi:10.1242/jeb.00203.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pilcher, Helen (2003). "Great Wall blocks gene flow". Nature News. Nature Publishing Group. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ Lu, Guoqing & Bernatchez, Louis (1998). "Experimental evidence for reduced hybrid viability between dwarf and normal ecotypes of lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis Mitchill)". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 265 (1400): 1025–1030. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wood (2001). "HybriDatabase: a computer repository of organismal hybridization data". Study Group Discontinuity: Understanding Biology in the Light of Creation. Baraminology. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ Breeuweri, Johanne & Werreni, John (1995). "Hybrid breakdown between two haploid species: the role of nuclear and cytoplasmic genes" (pdf). Evolution. 49 (4): 705–717. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "NCSE Resource". Cans and Can`ts of Teaching Evolution. National Center for Science Education. 2001-02-13. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (1991). "Opus 200". Stephen Jay Gould Archive. Natural History. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- ^ Wright, Sewall (September 1980). "Genic and Organismic Selection". Evolution. 34 (5): 825. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1976). The Selfish Gene (1st Edition ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 33. ISBN 0192860925. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Gould SJ, Lloyd EA (1999). "Individuality and adaptation across levels of selection: how shall we name and generalize the unit of Darwinism?". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (21): 11904–9. PMID 10518549. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Sedjo, Roger (2007). "How many species are there?". Environmental Literacy Council. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

Further reading

Chronological order of publication (oldest first)

- Darwin, Charles (1996), Beer, Gillian (ed.), The origin of species, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 019283438X

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Gamlin, Linda (1998). Evolution (DK Eyewitness Guides). New York: DK Pub. ISBN 0751361402.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Howard, Jonathan (2001). Darwin: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192854542.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Liam Neeson (narrator). Evolution: a journey into where we're from and where we're going (web resource) (DVD). South Burlington, VT: WGBH Boston / PBS television series Nova. ASIN B00005RG6J. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

{{cite AV media}}: Unknown parameter|date2=ignored (help) - Age level: Grade 7+ - Burnie, David (2002). Evolution. New York: DK Pub. ISBN 078948921X.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Horvitz, Leslie Alan (2002). The complete idiot's guide to evolution. Indianapolis: Alpha Books. ISBN 0028642260.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Charlesworth, Deborah; Charlesworth, Brian (2003). Evolution: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192802518.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sis, Peter (2003). The tree of life: a book depicting the life of Charles Darwin, naturalist, geologist & thinker. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux. ISBN 0-374-45628-3.

- Thomson, Keith Stewart (2005). Fossils: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192805045.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Greg Krukonis (2008). Evolution For Dummies (For Dummies (Math & Science)). For Dummies. ISBN 0-470-11773-7.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)

External links

- Brain, Marshall, "How Evolution Works", How Stuff Works: Evolution Library (web resource), Howstuffworks.com, retrieved 2008-01-24

- Carl Sagan. Carl Sagan on evolution (Google video) (streaming video). Google. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

{{cite AV media}}: Unknown parameter|date2=ignored (help) - Carl Sagan. Theory of Evolution Explained (Youtube video) (streaming video). Youtube. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

{{cite AV media}}: Unknown parameter|date2=ignored (help) - Evolution Education Wiki: EvoWiki (web resource), retrieved 2008-01-24

- "The Big Picture on Evolution (PDF)" (PDF), The Big Picture Series, Wellcome Trust, January 2007, retrieved 2008-01-23

- The Talk Origins Archive: Exploring the Creation/Evolution Controversy (web resource), retrieved 2008-01-24

- Understanding Evolution: your one-stop source for information on evolution (web resource), The University of California Museum of Paleontology, Berkeley, retrieved 2008-01-24

- University of Utah Genetics Learning Center animated tour of the basics of genetics (web resource), Howstuffworks.com, retrieved 2008-01-24