Alfred Russel Wallace

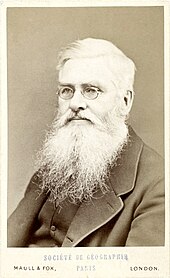

Alfred Russel Wallace OM (born January 8, 1823 in Usk , Monmouthshire in Wales , † November 7, 1913 in Broadstone, Dorset in England ) was a British naturalist . Its official botanical author abbreviation is " Wallace ".

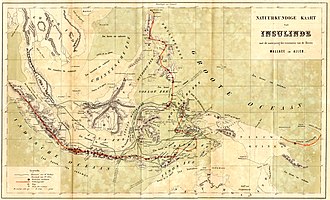

During his stay in the Malay Archipelago , he recognized that there was a biogeographical boundary between the Indonesian islands of Borneo and Celebes , which was later named the Wallace Line after him . Independently of Charles Darwin , he developed ideas for the theory of evolution . In his later years he was also involved in social issues.

Live and act

childhood and education

Alfred Russel Wallace was born in the village of Llanbadoc near Usk in Monmouthshire as the eighth child of Thomas Vere Wallace (1771-1843) and Mary Anne Greenell (1788-1868). His father, originally from Scotland, who studied law but never worked as a lawyer, traced his origins back to William Wallace . His mother came from a Huguenot family from Hertford .

From 1828 Wallace attended Richard Hale High School in Hertford until financial difficulties forced his family to take him out of school in 1836. Wallace moved to London to live and work with his older brother, John, a 19 year old apprentice construction worker. However, this was only a temporary measure until his eldest brother William took him on as an apprentice surveyor. During this time he attended lectures and read books at the London Mechanics' Institute , where he met the radical political ideas of social educators like Robert Owen and Thomas Paine . He left London in 1837 to live with William for six years and work as an apprentice watchmaker and surveyor. In late 1839 they moved to Kington, near the Wales border, before settling in Neath in Glamorgan . Between 1840 and 1843 Wallace worked as a surveyor in eastern England and Wales. By late 1843, William's business had declined due to difficult economic conditions. Wallace then left at the age of 20.

After a short period of unemployment, he was employed as a draftsman, cartographer and surveyor at the Collegiate College in Leicester . Wallace spent a lot of time at the public library, where he An Essay on the Principle of Population by Thomas Malthus one evening reading and Henry Bates first met. Bates befriended Wallace and got him to collect insects . His brother William died in March 1845 and Wallace left his job to run his brother's company in Neath, but he and his brother John were unable to keep the business going. After a few months, Wallace found work as a civil engineer at a nearby company involved in a project to build a railway in the River Neath valley . The work as a surveyor allowed him to spend a lot of time in the country and to devote himself to his new passion - collecting insects. Wallace was able to convince his brother John to start a new architectural and civil engineering company that carried out various projects, including a. the construction of the Mechanical Institute at Neath. William Jevons, founder of the institute, was impressed by Wallace and persuaded him to give lectures on science and engineering there. In the fall of 1846, at the age of 23, Wallace and his brother John were able to buy a cabin near Neath where they lived with their mother and sister, Fanny. During this period, Wallace was an avid reader and exchanged letters with Bates on the anonymous work Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation , as well as The Voyage of the Beagle by Charles Darwin and Principles of Geology by Charles Lyell .

Exploring and studying nature

Inspired by the travel reports of past and contemporary traveling naturalists, including Alexander von Humboldt , Ida Pfeiffer , Charles Darwin and above all William Henry Edwards , Wallace decided that he too wanted to travel abroad as a naturalist. In 1848 Wallace and Bates began the voyage to Brazil on board the ship Mischief . They intended to collect insects and other animal species living in the Amazon basin and sell them to collectors in the UK. They hoped to find evidence of the species' transmutation . Wallace and Bates spent most of the first year collecting near Belém do Pará and then exploring inland separately, meeting sporadically to discuss their finds. In 1849 they were joined by the young botanist Richard Spruce and Wallace's younger brother Herbert. Herbert left her after a short time. He died of yellow fever two years later. Spruce and Bates spent ten years collecting in South America.

Wallace continued mapping the Rio Negro for four years and collected more specimens. He made notes of the people and languages he encountered, as well as geography, flora, and fauna. On July 12, 1852, Wallace began the return trip to England on board the brig Helen . After 25 days at sea (around 9:00 a.m. on August 6), Balsam caught fire in the ship's cargo and the crew were forced to leave the ship. Wallace's entire collection was lost and he was only able to save part of his diary and a few drawings. Wallace and crew spent ten days on an open boat before being rescued by the brig Jordeson (at 5:00 p.m. on August 15), which was sailing from Cuba to London. The Jordeson's supplies were drained by the unexpected passengers, but after a difficult passage with very small rations, the ship finally reached its destination on October 1, 1852.

After his return to England, Wallace spent 18 months in London and lived off the insurance of his lost collection and the sale of some specimens that had been sold to the Indian settlement of Jativa in the Orinoco basin and to Micúru ( Mitú ) on before beginning his exploration of the Rio Negro Río Vaupés had been shipped back to the UK. During this time, although almost all the notes had been lost on his expedition to South America, he published six articles (including On the Monkeys of the Amazon ) and the two books Palm Trees of the Amazon and Their Uses ( palm trees from the Amazon and their use ) and Travels on the Amazon ( traveling in the Amazon ). He made contact with other British naturalists.

From 1854 to 1862 Wallace toured the Malay Archipelago collecting specimens for sale and for his nature studies. His observations of the marked zoological differences across a small strait between Bali and Lombok led to the hypothesis of a zoogeographical boundary, now known as the Wallace Line . Wallace collected 125,660 specimens (including 310 mammals, 100 reptiles, 8,050 birds, 7,500 mussels, 13,100 butterflies, 83,200 beetles and 13,400 other insects) in the Malay Archipelago. More than a thousand of them were previously undescribed species. A set of 80 bird skeletons that he collected in Indonesia and the accompanying documentation can be found in the Cambridge University Museum of Zoology . Wallace had up to a hundred assistants who collected on his behalf. Among these, his most trusted assistant was a Malay named Ali, who later called himself Ali Wallace . While Wallace was collecting insects, many of the bird specimens were collected by his assistants, including about 5,000 specimens collected and prepared by Ali.

One of his better-known descriptions made during this trip is that of the Wallace's flying frog ( Rhacophorus nigropalmatus ). During his voyage of exploration, he refined his reflections on evolution and had his well-known inspiration for natural selection .

He published a description of his studies and adventures in 1869 under the title The Malay Archipelago , which was one of the most popular scientific works of the 19th century and which was frequently reissued into the 1920s. It has been praised by scholars such as Darwin (to whom it was dedicated) and Charles Lyell, and by laypeople such as novelist Joseph Conrad , who called it his "bedtime reading of choice" and used it as a source of information for some of his novels (especially Lord Jim ).

Return to England, marriage and children

In 1862 Wallace returned to England and moved in with his sister Fanny Sims and her husband Thomas. While recovering from his travels, he sorted his collections and gave numerous lectures on his adventures and discoveries at scientific societies such as the Zoological Society of London . He visited Darwin at the Down House and met Charles Lyell and Herbert Spencer . During the 1860s he wrote publications and gave lectures defending the theory of natural selection. He used letters to Darwin, in which he discussed various topics, such as B. the sexual selection , the warning color and the possible effect of the natural selection on the hybridization and the divergence of the species responded. After a year of courtship, Wallace became engaged to a young woman in 1864 whom he referred to in his autobiography as Miss L. To his great disappointment, however, she broke off the engagement.

In 1866 he and Annie Mitten married, whom he had met through Richard Spruce, who was a good friend of Annie's father, William Mitten (1819-1906), a moss expert. In 1872 Wallace built a concrete house on leased land in Grays , Essex, where he lived until 1876. The couple had three children: Herbert (1867–1874), who died in childhood, Violet (1869–1945) and William (1871–1951).

Since 1865 he was concerned with spiritualism .

Financial difficulties

In the late 1860s and 1870s, Wallace was very concerned about the financial security of his family. During his time in the Malay Archipelago, selling his copies had made him a substantial sum of money, carefully invested by the agent who sold them. When Wallace returned to the UK, he made various bad investments in railways and mines, which lost most of his fortune, leaving him dependent on the proceeds of his publication The Malay Archipelago . Despite the help of his friends, he was unable to find permanent employment with a fixed wage, such as B. that of a museum director. To stay solvent, he worked as a grader of government exams, wrote 25 publications between 1872 and 1876 for a modest sum of money, and was rewarded by Lyell and Darwin for helping edit some of their own works. To avoid having to sell parts of his personal property, Wallace needed an advance of £ 500 in 1876, which his publisher, editor of The Geographical Distribution of Animals , granted him.

Darwin was well aware of Wallace's financial plight and struggled long and hard to get him a government pension for his scientific services. When Wallace received this from 1881, his financial situation stabilized as the pension supplemented the income from his writings.

Social activism

Wallace had written only a handful of articles on political and social issues between 1873 and 1879. Before that, John Stuart Mill had become aware of Wallace because Wallace had incorporated critical remarks about English society in The Malay Archipelago . Mill asked Wallace to join his Land Tenure Association , but the society was dissolved after Mill's death in 1873.

In 1879 Wallace participated actively in the discussion of trade principles and land reform. He believed that rural areas should be owned by the state, which would then lease them to individuals. They would process these in a way that would benefit the greater part of the population. The often abused power of rich landowners in English society would thus be broken. 1881 Wallace was elected president of the newly formed company for land nationalization ( country Nationalization Society selected). In 1882 he published his book land nationalization; Need for and objectives ( country Nationalization; Its Necessity and Its Aims ) on this subject. He criticized the negative impact British free trade regulations had on the working class.

Wallace continued his scientific work in parallel with his social activities. In 1880 he published Iceland Life ( life on islands ) as a result of the work of The Geographical Distribution of Animals ( The geographical distribution of animals ).

Trip to the United States

In November 1886 Wallace went on a ten-month trip to the United States to give a series of popular lectures. Most of the lectures were on Darwinism (evolution and natural selection), but he also had discussions on biogeography , spiritualism and socio-economic reforms. During the trip he met his brother John, who had emigrated to California years earlier. He also spent a week with American botanist Alice Eastwood as a tour guide in Colorado. There he examined the flora of the Rocky Mountains . He also met other well-known American naturalists and looked at their collections.

The last few decades

In his 1889 book Darwinism , Wallace used information from his trip to America and information that he had compiled for his lectures.

That same year he was reading the book Looking Backward ( rear viewing ) by Edward Bellamy and described himself as a socialist. These ideas led him to speak out against both social Darwinism and eugenics . This attitude was shared by other prominent evolutionary thinkers of the 19th century, who believed that society was too corrupt and too unjust to be able to select people according to their fitness.

In 1891 he published in English and American Flower ( English and American Flowers ), a theory that could explain the ice ages, various similarities between the flora of Europe, Asia and North America.

In 1898 Wallace wrote a paper ( Paper Money as a Standard of Value ) in which he advocated the introduction of a pure money paper system in which the currency is not supported by silver or gold reserves. This impressed the economist Irving Fisher so much that he dedicated his book Stabilizing the Dollar to Wallace in 1920 . Wallace wrote extensively on other social issues, including his support for women's suffrage and the dangers and wastes of militarism . He continued his social activism until the end of his life and published his book The Revolt of Democracy only weeks before his death.

death

Alfred Russel Wallace died on November 7, 1913 at the age of 90 in his country house, Old Orchard ( old orchard ). His death was widely reported in the press. The New York Times called him “the last of the giants to be part of the wonderful group of intellectuals that u. a. Darwin, Huxley, Spencer, Lyell and Owen, and whose daring research revolutionized and developed the thought of the century ”. Another reporter in the same issue wrote: "There is no need to justify the few literary or scientific weirdnesses of the author of this grandiose book Malay Archipelago ".

Some of Wallace's friends suggested that he be buried at Westminster Abbey , but his wife followed suit and buried him in the small cemetery at Broadstone, Dorset . A number of prominent British scholars formed a committee to place a plaque in honor of Wallace near Darwin's grave in Westminster. The memorial plaque was unveiled on November 1, 1915.

Evolution theory

Early thinking about evolution

Wallace began his career as a naturalist and believed early on in a transmutation of species . It was developed by Robert Chambers work Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation affected. In 1845 Wallace wrote to Henry Bates :

“I have a far more agreeable opinion on 'Vestiges' than you seem. I don't think it is a hasty generalization, but rather a resourceful hypothesis, backed by some striking facts and analogies, but which has yet to be confirmed by other facts and by additional light that more research may shed on the problem. It is a topic that every nature student can devote himself to. Every fact that he observes will speak either for or against and therefore it serves as a stimulus for the compilation of facts and as an object at the same time, to which these can be applied when raised. "

Wallace planned some of his fieldwork in advance so that the hypothesis that closely related species would inhabit adjacent areas under an evolutionary scenario could be tested. While working in the Amazon Basin, he realized that geographic barriers such as B. the Amazon river and its larger tributaries, often separated the ranges of closely related species. He took these observations in his publication On the Monkeys of the Amazon ( About the monkeys on Amazon ) on. Near the end of the article, he asks the question, "Are closely related species ever separated by a large rural distance?"

In February 1855, when he in Sarawak on the island of Borneo worked, wrote Wallace On the Law Which has Regulated the Introduction of Species ( About the law which regulated the introduction of species ), a document which in the Annals and Magazine of Natural History published in September 1855. Here he recorded and listed general observations that concerned the geographical and geological distribution of species ( biogeography ). His conclusion that each species coincided in time and place with closely related species is known today as the “ Sarawak Law ”. This is how Wallace answered the question he asked in his earlier publication about the monkeys in the Amazon basin. Although it made no mention of possible evolutionary mechanisms, the paper was a harbinger of the momentous article he wrote three years later.

This publication shattered Charles Lyell's belief that species were immutable. Although his friend Charles Darwin wrote to him in 1842 and expressed his support for the idea of transmutation, Lyell persisted in his rejection of the idea. In early 1856 Darwin was referred to the Wallace document by Lyell and Edward Blyth . Lyell was more impressed and started with a species notebook that looked at the implications of this, particularly on human ancestry. Darwin had already presented his theory to their mutual friend Joseph Hooker and was now explaining to Lyell all the details of natural selection for the first time. Although Lyell couldn't agree with it, he urged Darwin to publish in order to get priority. Darwin initially raised concerns, but on May 14, 1856, began compiling an outline of his ongoing work.

Natural selection and Darwin

In February 1858, Wallace was already convinced of the validity of evolution through his biogeographical research on the Malay Archipelago. As he wrote in his later autobiography:

“The problem was not just how and why the species change, but how and why they change into new and well-defined species that differ from one another in so many ways, why and how they adapt so precisely to the different living conditions and why the intermediate stages become extinct (since geology shows that they are extinct) and only leave clearly defined and strongly defined species, genera and higher animal groups. "

According to his autobiography, Wallace pondered Thomas Malthu's idea of positively limiting human population growth when he was in bed with a fever and the idea of natural selection occurred to him. Wallace wrote in his autobiography that he was on the island of Ternate at the time , but historians have questioned that, claiming that it was more likely based on his collection entries that he was on the island of Gilolo . Wallace describes this as follows:

“It occurred to me at the time that these causes or their equivalents are also constantly at work in the case of animals, and since animals reproduce much faster than humans, the annual annihilation due to these causes must be enormous, by the number of members each Kind to keep it low, since it obviously does not increase from year to year, otherwise the world would be overpopulated by those that multiply the fastest. Pondering indefinitely about the enormous and constant destruction that ensues, I wondered why some die and some survive. And the answer was clear, the more suitable survive. And if you take into account the considerable variation that my experience as a forager had shown me to exist, then it followed that whatever changes the species needed to adapt to the changing conditions would come from it. In this way every part of the animal's structure could be changed exactly as required and in the process of these changes the unchanged would become extinct and so the defined and clearly isolated characteristics of each new species would be explained.

Before he left for the East in 1854, Wallace had briefly met Darwin once. From 1857 onwards they were in regular contact by letters and exchanged views on their publications, theories and findings. Wallace kept Darwin's letters carefully, even if the first few were lost. In the first documented letter of May 1, 1857 commented Darwin that both Wallace's letter of 10 October and its publication on the Law did has regulated the Introduction of New Species ( About the law that the introduction of new species regulated showed) that both thought similar, and that to some extent they had drawn similar conclusions. He added that he was preparing his own release for publication in about two years. Wallace trusted the opinion of Darwin and sent him his essay On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely From the Original Type ( About the tendency of species to indefinitely from the original type to remove ) on March 9, 1858 with the request, review it and forward it to Charles Lyell if he thought it would be worth it. On June 1, 1858, Darwin received the manuscript from Wallace. Although the paper did not use the term "natural selection" explicitly, it explained the mechanisms of evolutionary divergence of species due to the pressures placed on them by the environment. In that sense, it was very similar to the theory Darwin had worked on for 20 years without making it public. Darwin sent the manuscript to Lyell with a letter in which he wrote: “He could not have made a better summary! I even use his terms as chapter headings. He does not say that I should publish, but of course I will write immediately and offer it to some specialist journal ”. Darwin, dismayed by his young son's illness, passed the problem on to Lyell and Joseph Hooker . They decided to publish the treatise in a joint presentation along with other unpublished writings that highlighted Darwin's priority. Wallace's treatise was presented to the Linnean Society of London on July 1, 1858, along with extracts from a pamphlet Darwin had privately presented to Hooker in 1847 and an 1857 letter to Asa Gray .

The response to the lecture was silent, while the chairman of the Linnean Society remarked in May 1859 that there had been no notable discoveries that year. But with Darwin's publication of On the Origin of Species ( The Origin of Species ) later in 1859, their meaning was obvious. When Wallace returned to Britain, he met with Darwin; afterwards the two were on friendly terms with each other. Over the years some people have doubted the validity of this version. In the early 1980s, two books were published, one by Arnold Brackman and one by John Langdon, in which it is even suggested that there was not only a conspiracy against Wallace to rob him of his due reputation, but that Darwin even had a key idea from Wallace to complete his own theory. These claims have been examined by other scholars who found them inconclusive.

After the publication of Darwin's On the Origin of Species , Wallace became one of their most staunch defenders. Darwin was particularly pleased with an incident in 1863: Wallace published a short text, Remarks on the Rev. S. Haughton's Paper on the Bee's Cell, And on the Origin of Species , to completely destroy the arguments of a geology professor at the University of Dublin, who criticized Darwin's comments in The Origin regarding the way the hexagonal cells in honeycombs had developed through natural selection. Another remarkable defense of The Origin was Creation by Law ( creation by law ), a treatise that Wallace in 1867 for The Quarterly Journal of Science wrote to the book The Reign of Law ( The rule of law ), that the Duke of Argyle as a challenge to natural selection had written to contradict. After a meeting of the British Association in 1870, Wallace wrote to Darwin complaining that "there are no opponents left who know anything about natural history, so there are no more of the earlier good discussions."

Differences between the theories of Darwin and Wallace

Historians of science have noted that there were some differences between Darwin's and Wallace's concepts of evolution, although Darwin viewed Wallace's ideas as essentially the same as his. Darwin emphasized the competition among individuals of the same species to survive and reproduce, while Wallace emphasized the biogeographical and environmental pressures that compel the species to adapt to local conditions.

Others have noted that another difference is that Wallace evidently viewed natural selection as a kind of feedback mechanism that kept the species adapted to their environment. They refer to a mostly overlooked paragraph of his famous publication from 1858:

“The effect of this principle is just like that of the governor of the steam engine, which corrects deviations before they become obvious and in the same way no unbalanced deficiency in the animal kingdom can reach a noticeable extent because it would have an immediate effect by having the Would make existence more difficult and make extinction an almost certain consequence. "

Warning coloring and sexual selection

In 1867, Darwin wrote to Wallace that it was difficult for him to understand why some caterpillars had developed noticeable colors. Darwin had come to believe that sexual selection , a phenomenon to which Wallace did not attach the same importance as Darwin, explained many striking colors in the animal world. However, Darwin realized that this might not be the case with the caterpillars. Wallace replied that he and Henry Bates had observed that many of the most spectacular butterflies had a peculiar smell and taste and that John Jenner Weir (1822-1894) had told him that birds would not eat a certain species of common white moth because of its bad taste. "Since the white moth is as conspicuous as a brightly colored caterpillar in the twilight," as Wallace wrote back to Darwin, "it is likely that the conspicuous color served as a warning against possible predators and could therefore have developed through natural selection". Darwin was impressed with the idea. At a subsequent meeting of the Entomological Society, Wallace asked for any evidence on the subject. In 1869, Weir published data from experiments and observations on brightly colored caterpillars that support Wallace's conjecture. Warning coloring was one of Wallace's contributions to the evolution of animal coloring in general and to the concept of protective coloring in particular. This was also part of a lifelong disagreement between Wallace and Darwin over the importance of sexual selection. In his book Tropical Nature and Other Essays ( Tropical Nature and other essays he wrote) 1878 in detail about the coloring of animals and plants and proposed alternative explanations of various cases before the Darwin of sexual selection was attributed. He wrote an extensive treatise on this in his 1889 book Darwinism .

Wallace effect

In Darwinism , Wallace defended natural selection. In it he postulated the hypothesis that natural selection could drive the reproductive separation of two species by strengthening the formation of barriers against hybridization . In this way it would help develop new species. He pointed out the following scenario: After two populations of a species have diverged beyond a certain point, each of them adapts to the particular environmental influences, with hybrid offspring being less well adapted than the respective parent species. At this point natural selection will tend to eliminate the hybrid. In addition, natural selection under such conditions would encourage the development of hybridization inhibitors, as individuals who avoid hybrid mating would produce better offspring and thus contribute to the reproductive isolation of both incipient species. This hypothesis came to be known as the Wallace Effect. As early as 1868, Wallace had suggested in letters to Darwin that natural selection could play a role in preventing hybridization, but had not worked this idea out in detail. It is still the subject of evolutionary biology research today, with both computer simulations and empirical results supporting its validity.

Application of Theory to Man

Published in 1864 Wallace the treatise The Origin of Human Races and the Antiquity of Man deduced from the Theory of Natural Selection ( origin of human races and ages of man, deduced from the theory of natural selection ), in which he theorized the people moved . Darwin had not yet dealt with the issue publicly, although Thomas Huxley in to Man's Place in Nature Evidence as ( evidence of the position of man in nature had done). Shortly thereafter, Wallace became a spiritualist , claiming that natural selection could not lead to mathematical, artistic or musical genius, as well as metaphysical thought, spirit and humor. He then claimed that something in the "invisible universe of the mind" intervened at least three times during evolution. The first time is the creation of life from inorganic matter. The second time the introduction of consciousness in higher animals. And the third time the formation of higher mental abilities in humans. He also believed that the reason for the existence of the universe was the development of the human mind.

The response to Wallace's ideas on the subject among the leading naturalists of the time varied. Charles Lyell was more likely than Darwin's to agree with Wallace's ideas. Many, however, including Huxley, Hooker, and even Darwin, were critical of Wallace. Darwin in particular was dismayed. He argued that there was no need for spiritual stimuli and that sexual selection could easily explain apparently non-adaptive mental phenomena.

As one historian of science has pointed out, Wallace's views on the subject contradicted two main tenets of the emerging Darwinian philosophy of the time, which held that evolution was neither teleological nor anthropocentric . While some historians have concluded that Wallace's belief that natural selection cannot explain the evolution of consciousness and the human mind is due to his spiritualism, other Wallace experts deny it. Some claim that Wallace never applied the principle of natural selection to them.

Evaluation of the role of Wallace in the theory of evolution

In many descriptions of the history of evolution, Wallace is mentioned only incidentally, simply as a “stimulus” for the publication of Darwin's own theory. In fact, Wallace developed stand-alone views that differed from Darwin's, and he was considered by many (especially Darwin) to be one of the leading thinkers on evolution of his time, whose ideas could not be ignored. A historian of science noted that both Darwin and Wallace exchanged knowledge through correspondence and publications, inspiring one another over time. Wallace is the most quoted author in Darwin's Descent of Man , often at strong contradiction to his own theories. Wallace remained a staunch defender of natural selection for the rest of his life. By 1880 evolution was widely accepted in scientific circles, but Wallace and August Weismann were virtually the only known biologists who believed that it was driven by natural selection.

spiritism

In 1861 Wallace wrote to his brother-in-law:

“I remain an utterly unbeliever in almost everything you hold to be sacred truths. I find the oft-repeated blame that skeptics hide evidence because it is not guided by Christian morality is extremely contemptible. I am grateful that I can see much that is admirable in all religions. For the bulk of humanity, religion is a kind of necessity. But whether there is a God and whatever His nature, whether or not we have an immortal soul, or whatever our condition after death, I don't have to be afraid to study nature and seek the truth , or believe that those who have lived according to a doctrine instilled in them in childhood will be better off in a future state that is a matter of blind faith rather than intelligent belief. "

Wallace was an avid phrenologist . Early on he experimented with hypnosis , then known as mesmerism . At Leicester he had used some of his students as test subjects with considerable success. When he began his experiments, the subject became very controversial, and early experimenters such as John Elliotson (1791–1868) received harsh criticism from the medical and scientific communities. Wallace combined his experience with mesmerism and his later studies on spiritism . In 1893 he wrote:

“Thus, I quickly learned my first lesson in examining these obscure areas of knowledge, never to attach importance to the doubts of great men or their allegations or allegations of narrowness when they stand in opposition to the repeated observation of other apparently sensible and honest men. The whole history of science shows us that whenever the educated and scientific men of any time have a priori rejected the facts of other researchers as absurd or impossible, those who rejected were always wrong. "

In the summer of 1865, Wallace began to study spiritualism, possibly at the suggestion of his older sister, Fanny Sims. After reviewing the literature on the subject and trying to test the phenomena he had observed at seances , he accepted that belief was linked to natural reality. For the rest of his life he remained convinced that at least some of the phenomena at the séances were authentic, regardless of allegations of deception by skeptics or evidence of tricks. Historians and biographers disagree on the factors most likely to have led to its acceptance of spiritism. One biographer suggested that the emotional shock he had experienced a few months earlier from breaking up with his fiancée had made him more receptive to spiritism. Other experts, on the other hand, have emphasized Wallace's will to find rational and scientific explanations for all phenomena, both material and non-material, the natural world and human society.

Spiritism was particularly popular with many of the Victorian-era educated who embraced traditional religious doctrine such as: B. those of the Church of England , found no longer acceptable, but who felt dissatisfied by a completely materialistic and mechanical view of the world, which increasingly arose from the scientific knowledge of the 19th century. However, some experts who have examined Wallace's views in detail point out that, for him, spiritualism was a matter of science and philosophy, and not a religious belief. Other prominent nineteenth-century intellectuals concerned with spiritualism were the social reformer Robert Owen , one of Wallace's early role models, as well as the physicists William Crookes and John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh , the mathematician Augustus De Morgan, and the Scottish Publisher Robert Chambers .

Wallace's strong public advocacy of spiritism, as well as his repeated defenses of spiritist media, accused of deception in the 1870s, damaged his scientific reputation. Tensions arose in formerly friendly relationships with scientists such as Henry Bates, Thomas Huxley, and Charles Darwin, who thought he was too gullible. Others, such as physiologist William Benjamin Carpenter and zoologist Ray Lankester , publicly attacked Wallace on the subject. Wallace and other scholars who defended spiritualism, such as William Crookes, have been the subject of harsh criticism from the press, particularly from The Lancet , a leading medical journal. The controversy hurt the public eye of Wallace's work for the rest of his career. When Darwin sought help from the naturalists to get Wallace a pension, Joseph Hooker replied:

“Wallace has lost a lot of class, not only because of his attachment to spiritualism, but also because he brought a discussion of spiritualism against the opinion of the entire committee in one of the British Association's section meetings. He is reported to have done this in an underhanded manner, and I well remember the outrage it generated in the Council of the British Association. "

Hooker finally gave in and agreed to support the pension application.

Biogeography and ecology

Wallace began work on an extensive study of the geographical distribution of species in 1872 at the urging of many of his colleagues including Darwin, Philip Sclater, and Alfred Newton . However, this project soon stalled, also because there was no developed taxonomy at that time and the classification systems of many animal species were in constant development. He did not resume work until 1874, after a series of papers on the problem of classification had appeared.

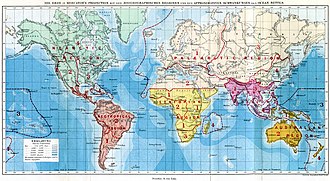

By expanding the system developed by Sclater for bird species, which divided the earth into six geographical zones, so that it also described mammals, reptiles, and insects, Wallace created the basis for the system of fauna regions that is used to this day. He discussed all known influencing factors that control the geographic distribution of animal species in the individual regions, such as the formation and decay of land bridges and the effects of temporary ice ages. He used maps to visualize the effect of factors such as the elevation of mountains, the depth of the oceans, and the character of regional vegetation, which influence the distribution of species. To do this, he put together all known species families and genera and listed their geographical distribution. The resulting two-volume work, The Geographical Distribution of Animals , was published in 1876 and was to remain one of the standard works in biogeography for the next 80 years ; An update was not published until the end of 2012.

In 1880 Wallace published the book Island Life , the sequel to the previously published The Geographical Distribution of Animals , in which he examined the distribution of plant and animal species on islands. Wallace divided islands into different types: ocean islands and continental islands. Ocean islands, such as the islands of Galapagos and Hawaii (then known as the Sandwich Islands ), which arose in the middle of the ocean and were never part of a large continent. Such islands were characterized by the absolute absence of all mammal and amphibian species living on the mainland (with the exception of migratory birds and species that were introduced as a result of human activities). They were the result of accidental colonization and subsequent evolution. He divided the continental islands into two groups, depending on whether they had been separated from the mainland for a long time (such as Madagascar ), or were more recently part of a large continent (such as the British Isles ). He investigated how this difference affected the native flora and fauna. The isolation of the islands could influence evolution and thus lead to the conservation of species such as the lemurs in Madagascar, which were once widespread on the continent. He discussed in detail how changes in the climate, especially ice ages, promote or prevent the spread of animal and plant species. The first part of the book deals with the possible causes of the great ice ages. At the time of its publication, Island Life was received as an important work and discussed extensively in numerous reviews and correspondence between scholars.

environmental issues

As part of his extensive studies of biogeography, Wallace was one of the first to describe the influence of humans on nature. In Tropical Nature and Other Essays (1878) he warned of the dangers of deforestation and soil erosion , especially in tropical areas with large amounts of precipitation . After becoming aware of the complex interactions between vegetation and climate, he warned that the excessive deforestation of tropical rainforests for coffee cultivation in Ceylon and India could adversely affect the climates of these countries and would later lead to their impoverishment because of the Soil erosion would make further cultivation impossible. In his book Island Life , Wallace took up the topic of deforestation again and described the effect of neobiota , i.e. invasive species that are introduced into fragile ecosystems by humans. He writes the following about the influence of European colonization on the island of St. Helena :

“When St. Helena was first discovered in 1501, it was densely covered with lush forest vegetation, with the trees towering over the seaward steep slopes and covering every part of the surface with an evergreen coat. This native vegetation has been almost completely destroyed; and although a myriad of alien plants have been introduced and more or less fully established, the island is now generally so barren and inaccessible that some people find it difficult to believe that it was once entirely green and fertile. However, the cause of the change is very easy to explain. The rich soil of decomposed volcanic rock and vegetable deposits could only hold up on the steep slopes as long as it was protected by the vegetation to which it owes its origins to a large extent. When it was destroyed, the heavy tropical rains soon washed away the soil, leaving behind a huge area of bare rock or sterile clay. This irreparable destruction was primarily caused by goats introduced by the Portuguese in 1513, which grew so rapidly that they existed by the thousands in 1588. These animals are the biggest of all enemies of the trees because they eat the young saplings and thus prevent the natural restoration of the forest. However, they were favored by the reckless waste of man. The East India Company took possession of the island in 1651, and by 1700 it became apparent that the forests were rapidly declining and in need of some protection. Two of the native trees, mammoth [redwood] and ebony [ebony], did well for tanning, and to avoid trouble, the bark was lavishly stripped from the trunks while the rest rotten. In 1709, a large amount of the rapidly disappearing ebony was used to burn lime to build fortifications! "

Wallace's comments on environmental degradation grew sharper later in his career. In The World of Life (1911) he wrote:

“These considerations should lead us to regard all works of nature, animate or inanimate, as endowed with a certain sacredness, so that they may be used by us but not misused and never ruthlessly destroyed or defaced. Polluting a source or river, destroying a bird or animal should be treated as a moral offense and a social crime; ... But during the last century, which has seen the great advances in the knowledge of nature of which we are so proud, there has been no corresponding development of love or reverence for her works; so that never before has there been such widespread devastation of the earth's surface through the destruction of the native vegetation and thus many animals and such extensive disfigurement of the earth through mineral mining and the fact that the waste from factories and cities was poured into our streams and rivers Has; and this has been done by all of the greatest nations that claim first place for civilization and religion! "

Engaging in other scientific and public controversies

Flat Earth Bet

In 1870, a flat earth proponent named John Hampden in a magazine ad offered anyone who could detect a convex curvature in a body of water such as a river, canal or lake a bet of £ 500 (roughly £ 48,000 adjusted for inflation as of 2020) on. Wallace, fascinated by the challenge and at the time short of money, designed an experiment (called the Bedford Level Experiment ) in which he set up two objects along a 10 km stretch of canal. Both objects were at the same height above the water, and he also mounted a telescope on a bridge at the same height above the water. When looking through the telescope, one object appeared higher than the other, showing the curvature of the earth.

The judge for the bet, the editor of Field magazine, declared Wallace the winner, but Hampden refused to accept the result. He sued Wallace and launched a multi-year campaign in which he wrote letters to various publications and organizations of which Wallace was a member, denouncing him as a cheater and thief. Wallace won several defamation suits against Hampden, but the resulting legal battle cost Wallace more than the wager, and the controversy frustrated him for years.

Anti-smallpox vaccination campaigns

In the early 1880s, Wallace took part in the political debate surrounding the introduction of compulsory smallpox vaccination in the UK. At first he viewed the vaccination primarily as incompatible with personal rights, but after studying the statistics, which were mainly disseminated by activists of the anti-smallpox vaccination campaigns, he had doubts about the effectiveness of the vaccination at all. At that time, the germ theory to explain the spread of diseases was not yet widespread and hardly recognized. Too little was known about the human immune system to understand how vaccinations work. During his research, Wallace came across a few cases where vaccination program supporters had used questionable statistics to reason. Wallace, always suspicious of any authority, came to the conclusion that the reduced incidence of smallpox after vaccination was due to the improved hygienic conditions. He also assumed that the practicing physicians had an interest in the introduction of the vaccination.

Wallace and other opponents of mandatory vaccination pointed out that vaccination was often carried out under unsanitary conditions and was therefore potentially dangerous in itself. In 1890 Wallace presented his results to a Royal Commission of inquiry , which dealt with the controversy. This criticized the error, in particular it described some of the statistics used as questionable. The Lancet medical journal alleges that he and other anti-vaccination activists used statistics selectively and ignored data that contradicted their position. The Royal Commission found the vaccination to be effective and recommended that vaccination be retained, but also some changes in vaccination methods to make the procedure safer. She also recommended the use of less severe penalties for refusing patients. Years later, in 1898, Wallace attacked the results of the commission again in a pamphlet; again followed in The Lancet the accusation that his arguments contained the same errors as the statistics originally submitted.

Astrobiology

Wallace's book Man's Place in the Universe , published in 1904, was the first serious attempt by a biologist to assess the probability of life on other planets . He came to the conclusion that the earth is the only planet in the solar system on which life is possible, largely because it is the only one on which water can exist in the liquid phase . More controversial was his claim that it was unlikely that other stars in the galaxy could have planets with the required properties (the existence of other galaxies was not proven at the time). His treatment of Mars in this book was brief, and in 1907 Wallace published the 110-page book Is Mars Habitable? (German: Is Mars habitable?) , a critique of Percival Lowell's theories that the Martian canals were created by intelligent beings. After several months of research and discussions with various experts, he finished his analysis of the Martian climate and atmospheric conditions. Among other arguments, he shows that the spectroscopic analysis could not detect any signs of water vapor in the Martian atmosphere, that Lowell's analysis of the Martian climate was subject to methodological errors, and significantly overestimated the surface temperature of the planet. In addition, the low atmospheric pressure would prevent water from becoming liquid, making an irrigation system spanning a planet completely impossible. Wallace was probably motivated to undertake this investigation because of his anthropocentric philosophical views.

Honors

- 1868 the Royal Medal of the Royal Society

- 1882 Honorary Doctorate from Dublin University

- 1889 Honorary Doctorate from Oxford University

- In 1892 the Founder's Medal of the Royal Geographical Society

- 1892 the Linné Medal of the Linnean Society of London

- 1893 member of the Royal Society

- 1908 Order of Merit of the Crown

- 1908 the Copley Medal of the Royal Society

- 1908 the Darwin-Wallace-Medal in gold of the Linnean Society

- 1910 Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh .

The lunar crater Wallace and the Martian Wallace crater are named after him. The dividing line between the biogeographical areas of Australia and Southeast Asia bears the name Wallace Line in his honor . In addition, numerous organisms are named after him, such as the Wallace bird of paradise ( Semioptera wallacii ) and the genus Wallacea Spruce of the plant family of the Ochnaceae , the genus Wallaceodendron Koord. From the family of the legumes (Fabaceae). or the pike cichlid species Crenicichla wallacii . The novel Wallace by the German writer Anselm Oelze was published in 2019 , which is based heavily on the actual biography and describes his relationship with Darwin.

Fonts (selection)

Books

English first editions

- Palm Trees of the Amazon and Their Uses . John Van Voorst, London 1853; (digitized version)

- A Narrative of Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro, With an Account of the Native Tribes, and Observations on the Climate, Geology, and Natural History of the Amazon Valley . Reeve & Co, London 1853.

- The Malay Archipelago; The Land of the Orangutan and the Bird of Paradise; A Narrative of Travel With Studies of Man and Nature . Macmillan & Co, London 1869, 2 volumes; digitized version: Volume 1 , Volume 2

- Contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection. A Series of Essays . Macmillan & Co, London / New York 1870. (digitized version)

- On Miracles and Modern Spiritualism. Three essays . James Burns, London 1875.

- The Geographical Distribution of Animals; With A Study of the Relations of Living and Extinct Faunas as Elucidating the Past Changes of the Earth's Surface . Macmillan & Co, London 1876 - 2 volumes

- Tropical Nature, and Other Essays . Macmillan & Co, London / New York 1878.

- Island Life: Or, The Phenomena and Causes of Insular Faunas and Floras, Including a Revision and Attempted Solution of the Problem of Geological Climates . Macmillan & Co, London 1880.

- Country nationalization; Its Necessity and Its Aims; Being a Comparison of the System of Landlord and Tenant With That of Occupying Ownership in Their Influence on the Well-being of the People . Trübner & Co, London 1882.

- Bad Times: An Essay on the Present Depression of Trade, Tracing It to Its Sources in Enormous Foreign Loans, Excessive War Expenditure, the Increase of Speculation and of Millionaires, and the Depopulation of the Rural Districts; With Suggested Remedies . Macmillan & Co, London / New York 1885.

- Darwinism; An Exposition of the Theory of Natural Selection With Some of Its Applications . Macmillan & Co, London & New York 1889; (digitized version)

- Natural Selection and Tropical Nature; Essays on Descriptive and Theoretical Biology . Macmillan & Co, London / New York 1891.

- The Wonderful Century; Its successes and its failures . Swan Sunshine & Co, London 1898.

- Studies Scientific and Social . Macmillan & Co, London 1900 - 2 volumes

- Man's Place in the Universe; A Study of the Results of Scientific Research in Relation to the Unity or Plurality of Worlds . Chapman & Hall, London 1903.

- My Life; A Record of Events and Opinions . Chapman & Hall, London 1905 - 2 volumes

- Is Mars Habitable? A Critical Examination of Professor Percival Lowell's Book "Mars and Its Canals", With an Alternative Explanation . Macmillan & Co, London 1907. (digitized version)

- The World of Life; A Manifestation of Creative Power, Directive Mind and Ultimate Purpose . Chapman & Hall, London 1910.

- Social Environment and Moral Progress . Cassell & Co, London / New York / Toronto / Melbourne 1913.

- The Revolt of Democracy . Cassell & Co, London / New York / Toronto / Melbourne 1913.

Facsimile edition:

- On the Organic Law of Change. A Facsimile Edition and Annotated Transcription of Alfred Russel Wallace's Species Notebook of 1855 to 1859 . Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA 2013.

German first editions

- The Malay Archipelago. The home of the orangutan and the bird of paradise. Travel experiences and studies about the country and its people. Authorized German edition by Adolf Bernhard Meyer , Westermann, Braunschweig 1869 ( Volume 1 , Volume 2 ).

- Darwinism. An exposition of the doctrine of natural selection and some of its uses . Friedrich Vieweg and Son, Braunschweig 1891 ( online ).

- Adventure on the Amazon and the Rio Negro . Edited by Matthias Glaubrecht . Galiani, Berlin 2014. ISBN 978-3-86971-085-3 .

Magazine articles

- On the Umbrella Bird (Cephalopterus ornatus), “Ueramimbé,” LG In: Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London . Volume 18, London 1850, pp. 206-207 ( online ).

- On the Monkeys of the Amazon . In: Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London . Volume 20, London 1852, pp. 107-110. (on-line)

- On the Law Which Has Regulated the Introduction of New Species . In: Annals and Magazine of Natural History . 2nd Series, Volume 16, London 1855, pp. 184-196. (on-line)

- On the Natural History of the Aru Islands . In: The Annals and Magazine of Natural History . 2nd series, supplement to volume 20, London 1857, pp. 473-485. (online) - a key work in island biogeography

- On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely From the Original Type . In: Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society: Zoology . Volume 3, No. 9, London 1858, pp. 53-62 ( online , BHL )

- On the Zoological Geography of the Malay Archipelago In: Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society: Zoology . Volume 4, London 1860, pp. 172-184. (online) - first description of the Wallace line

- On the Physical Geography of the Malay Archipelago In: Journal of the Royal Geographical Society . Volume 33, London 1863, pp. 217-234. (on-line)

- Remarks on the Rev. S. Haughton's Paper on the Bee's Cell, And on the Origin of Species . In: Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 3rd Series, Volume 12, London 1863, pp. 303-309. (on-line)

- The Origin of Human Races and the Antiquity of Man Deduced from the Theory of Natural Selection . In: Journal of the Anthropological Society of London . Volume 2, 1864, pp. CLVIII-CLXXXVII ( doi: 10.2307 / 3025211 ).

- The Scientific Aspect of the Supernatural . In: The English Leader . Volume 2, 1866.

- English and American Flowers . In: Fortnightly Review . Volume 50, London 1891, pp. 525-534 and pp. 796-810. (on-line)

- Paper Money as a Standard of Value . In: Academy . Volume 55, 1898, pp. 549-550. (on-line)

A list of all published articles and essays can be found in James Marchant: Alfred Russel Wallace. Letters and Reminiscences. Volume II, from p. 258. (online)

proof

literature

- Janet Browne: Charles Darwin: Voyaging: Volume I of a Biography . Princeton University Press, 1995, ISBN 1-84413-314-1 .

- Adrian Desmond, James Moore: Darwin . List Verlag, Munich / Leipzig 1991, ISBN 3-471-77338-X .

- Edward J. Larson : Evolution: The Remarkable History of Scientific Theory. Modern Library, 2004, ISBN 0-679-64288-9 .

- Christopher McGowan: The Dragon Seekers . Perseus Publ, Cambridge 2001, ISBN 0-7382-0282-7 .

- James Marchant: Alfred Russel Wallace. Letters and Reminiscences. Harper and Brothers Publishers, New York / London 1916, Volume 1 , Volume 2

- EB Poulton: Alfred Russel Wallace. In: Nature. Volume 92, No. 2299, pp. 347-349, 1913, doi: 10.1038 / 092347c0 .

- Peter Raby: Alfred Russel Wallace: A Life . Princeton University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-691-10240-6 .

- Michael Shermer: In Darwin's Shadow: The Life and Science of Alfred Russel Wallace: A Biographical Study on the Psychology of History . Oxford University Press, New York 2002, ISBN 0-19-514830-4 .

- Ross A. Slotten: The Heretic in Darwin's Court: The Life of Alfred Russel Wallace . Columbia University Press, New York 2004, ISBN 0-231-13010-4 .

- John van Wyhe: Dispelling the Darkness. Voyage in the Malay Archipelago and the Discovery of Evolution by Wallace and Darwin . World Scientific Publishing Company, Singapore 2013.

- John Wilson: The Forgotten Naturalist: In Search of Alfred Russel Wallace . Australian Scholarly Publishing, Arcadia 2000, ISBN 1-875606-72-6 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Raby Bright Paradise pp. 77-78.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq Slotten The Heretic in Darwin's Court

- ↑ Shermer In Darwin's Shadow p. 53.

- ↑ Wilson pp. 19-20.

- ^ Raby Bright Paradise p. 78.

- ↑ Wilson p. 36; Raby Bright Paradise pp. 89, 98-99, 120-121.

- ^ Raby Bright Paradise pp. 89-95.

- ↑ Shermer In Darwin's Shadow p. 72.

- ↑ Slotten p. 86.

- ↑ Wilson pp. 42-43.

- ^ Wilson p. 45.

- ^ Raby Bright Paradise , p. 148.

- ↑ Shermer In Darwin's Shadow p. 14.

- ^ University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge | Historical significance . Museum.zoo.cam.ac.uk. April 18, 2009. Archived from the original on November 19, 2010. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ↑ John Van Wyhe, Gerrell M. Drawhorn: 'I am Ali Wallace': The Malay Assistant of Alfred Russel Wallace . In: Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society . 88, 2015, pp. 3-31. doi : 10.1353 / ras.2015.0012 .

- ↑ Shermer pp. 151-152.

- ↑ Shermer In Darwin's Shadow, p. 156.

- ^ Alfred Wallace: Bibliography of the Published Writings of Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913) . The Alfred Russel Wallace Page hosted by Western Kentucky University . Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- ↑ Shermer pp. 274-78.

- ↑ Shermer pp. 23, 279.

- ↑ Shermer p. 54.

- ↑ Larson Evolution p. 73.

-

↑ Desmond / Moore 1991 (German edition), p. 498

Browne Charles Darwin: Voyaging pp. 537-546. - ^ Wallace My Life p. 361.

- ^ Wallace My Life pp. 361-362.

- ↑ James Marchant: Alfred Russel Wallace Letters and Reminiscences Volume I, Cassell And Company, 1916. p. 105.

- ^ Wallace: Letters and reminiscences 1916. p. 105.

- ^ Francis Darwin: The life and letters of Charles Darwin . 1887 p. 95.

- ^ A b Alfred Wallace: On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely From the Original Type . The Alfred Russel Wallace Page hosted by Western Kentucky University . Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- ↑ Slotten, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Francis Darwin: The life and letters of Charles Darwin . 1887 p. 116.

- ↑ a b Browne: Charles Darwin: The Power of Place . Pp. 33-42.

- ↑ Michael Shermer: In Darwin's Shadow: Excerpt . michaelshermer.com. Retrieved April 29, 2008.

- ^ Charles Smith: Responses to Questions Frequently Asked About Wallace: Did Darwin really steal material from Wallace to complete his theory of natural selection? . The Alfred Russel Wallace Page hosted by Western Kentucky University . Retrieved April 29, 2008.

- ^ Alfred Wallace: Creation by Law (S140: 1867) . The Alfred Russel Wallace Page hosted by Western Kentucky University . Retrieved May 23, 2007.

- ^ Kutschera: A comparative analysis of the Darwin-Wallace papers and the development of the concept of natural selection . In: Theory in Biosciences . 122, No. 4, December 19, 2003, pp. 343-359. doi : 10.1007 / s12064-003-0063-6 .

- ^ Larson p. 75.

- ^ Bowler, More p. 149.

- ^ Charles H. Smith: Wallace's Unfinished Business . Complexity (publisher Wiley Periodicals, Inc.) Volume 10, No 2, 2004. Retrieved May 11, 2007.

- ^ J. Ollerton: Flowering time and the Wallace Effect . In: Heredity . Volume 95, pp. 181-182, 2005 ( doi: 10.1038 / sj.hdy.6800718 )

- ^ Wallace: Darwinism p. 477.

- ↑ Larson p. 100.

- ↑ Shermer p. 160.

- ↑ Shermer pp. 208-209.

- ↑ Shermer pp. 157-160.

- ^ Charles H. Smith: Alfred Russel Wallace: Evolution of an Evolutionist Chapter Six. A change of mind? . The Alfred Russel Wallace Page hosted by Western Kentucky University . Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ↑ Shermer p. 149.

- ^ Larson p. 123.

- ^ Bowler, More p. 154.

- ^ Alfred Wallace: 1861 Letter from Wallace to Thomas Sims . The Alfred Russel Wallace Page hosted by Western Kentucky University . Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ^ Charles H. Smith: Alfred Russel Wallace: Evolution of an Evolutionist Chapter One. Belief and Spiritualism . The Alfred Russel Wallace Page hosted by Western Kentucky University . Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ^ Alfred Wallace: Notes on the Growth of Opinion as to Obscure Psychical Phenomena During the Last Fifty Years . The Alfred Russel Wallace Page hosted by Western Kentucky University . Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ↑ a b c Shermer S.?

- ↑ Ben G. Holt et al. a .: An Update of Wallace's Zoogeographic Regions of the World. In: Science . Volume 339, No. 6115, 2012, pp. 74-78, doi: 10.1126 / science.1228282

- ↑ Julia Krohmer: The new world order of animals: Wallace map updated after almost 150 years. Senckenberg Research Institute and Nature Museums, press release from December 20, 2012 from the Science Information Service (idw-online.de), accessed on July 7, 2019.

- ^ Wallace Island Life , 2nd Ed., 1892, pp. 294-295.

- ^ Wallace World of Life p. 279.

- ↑ Shermer pp. 258-61.

- ↑ Shermer p. 216.

- ↑ Shermer p. 294.

- ^ Fellows Directory. Biographical Index: Former RSE Fellows 1783–2002. (PDF file) Royal Society of Edinburgh, accessed April 20, 2020 .

- ↑ Lotte Burkhardt: Directory of eponymous plant names - Extended Edition. Part I and II. Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin , Freie Universität Berlin , Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-946292-26-5 doi: 10.3372 / epolist2018 .

- ↑ Anselm Oelze: Wallace . Schöffling & Co., Frankfurt am Main 2019, ISBN 978-3-89561-132-2 (262 pages).

further reading

- Barbara G. Beddall: Wallace, Darwin and the Theory of Natural Selection. A Study in the Development of Ideas and Attitudes. In: Journal of the History of Biology. Volume 1, 1968, pp. 261-323.

- Andrew Berry : Infinite Tropics. To Alfred Russel Wallace Anthology. Verso, London / New York 2002, ISBN 1-85984-652-1 .

- Peter J. Bowler: Alfred Russel Wallace's Concepts of Variation. In: Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. Volume 31, 1976, pp. 17-29.

- Arnold C. Brackman : A delicate arrangement. The strange Case of Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. Times Books, New York 1980, ISBN 0-8129-0883-X .

- John Langdon Brooks: Just Before the Origin: Alfred Russel Wallace's Theory of Evolution. iUniverse, 1999, ISBN 1-58348-111-7 .

- James T. Costa: Wallace, Darwin, and the Origin of Species. Harvard University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0-674-72969-8 .

- Martin Fichman: An Elusive Victorian. The Evolution of Alfred Russel Wallace . University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London 2004, ISBN 0-226-24613-2 .

- Ulrich Kutschera : Design Flaws in Nature: Alfred Russel Wallace and Godless Evolution. Lit-Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-643-12133-2 .

- H. Lewis McKinney: Wallace and Natural Selection. Yale University Press, New Haven / London 1972, ISBN 0-300-01556-9 .

- Efram Sera-Shriar: Credible Witnessing: AR Wallace, spiritualism and a "new branch of anthropology" . In: Modern Intellectual History , Volume 17, Number 2, 2020, pp. 357-384 ( doi: 10.1017 / S1479244318000331 ).

- Tim Severin: The Spice Islands Voyage: The Quest for Alfred Wallace, the Man Who Shared Darwin's Discovery of Evolution . Ulverscroft Large Print, 1998, ISBN 0-7867-0721-6 .

- Amabel Williams-Ellis: Darwin's moon. A Biography of Alfred Russel Wallace. Blackie, London / Glasgow 1966, ISBN 0-216-88398-9 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Alfred Russel Wallace in the catalog of the German National Library

- Literature by and about Alfred Russel Wallace in the catalog of the Virtual Library of Biology (vifabio)

- Author entry and list of the described plant names for Alfred Russel Wallace at the IPNI

- Correspondence with Charles Darwin

- Entry to Wallace; Alfred Russel (1823–1913) in the Archives of the Royal Society , London

- Alfred Russel Wallace Page - biography, bibliography and original texts

- The Alfred Russel Wallace Website - Comprehensive information in English

- Wallace (online) - " the first complete edition of the writings of naturalist and co-founder of the theory of evolution Alfred Russel Wallace "

- Wallace Letters (online)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wallace, Alfred Russel |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British zoologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 8, 1823 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Usk , Monmouthshire |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 7, 1913 |

| Place of death | Broadstone , Dorset |