Étienne François Geoffroy

Étienne François Geoffroy , also Geoffroy the Elder, (born February 13, 1672 in Paris , † January 6, 1731 in Paris) was a French chemist who was a trained pharmacist and then a practicing doctor . His brother Claude-Joseph Geoffroy (Geoffroy the Younger) was also a chemist. He is known for creating tables of chemical affinities.

Live and act

Born in Paris as the son of a pharmacist, Matthieu-François Geoffroy (1644–1708), Geoffroy became interested in chemistry through conversations in his father's house with scientists such as Wilhelm Homberg . After apprenticeship as a pharmacist, he studied botany, chemistry and anatomy with his father in Paris and from 1692 in Montpellier , where he graduated as a pharmacist in 1693 . He joined Marshal Tallards' diplomatic mission in London in 1698. There he made friends with Hans Sloane , on whose proposal he was elected on July 6, 1698 to a member ( Fellow ) of the Royal Society . He then traveled through the Netherlands and Italy . Originally, as the eldest son, he was supposed to take over the father's pharmacy, but he was more interested in medicine and natural sciences and left that to his brother. In 1704 he received a doctorate in medicine in Paris. The title of the dissertation was Theses ergo hominis primordia vermis (1704). In it he assumed that there are openings in the seminal vesicle and ovary that receive the fertilizing substance . He already recognized the sexes of plants and fertilization by pollen and published about it in 1711 (although he had a forerunner in Samuel Morland ). He tried to explain the colors of plants from the fact that they consist of an essential oil and volatile salts.

In 1707 he became professor of chemistry at the Jardin des Plantes . In 1709 he was appointed professor of medicine and chemistry at the Collège Royal . From 1726 to 1729 he was Dean of the Medical Faculty of Paris.

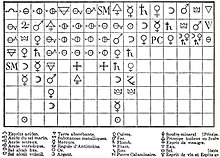

His first publication on the heat of mixing of salts appeared in 1700. In 1718 he discovered the principle of affinity in chemistry and developed an affinity table (kinship table), on which he worked in the following years. His kinship tables were lists that were created by collecting observations while mixing different chemical substances with one another. The lists show the affinity of the same chemicals for different reagents and used early chemical symbols for elements. These kinship relationships lasted until the end of the century, when they were replaced with a more sound concept by Claude Louis Berthollet .

In 1718 he recognized that burning alcohol produces water and in 1731 he clarified the nature of the salt of the Seignette . He made Berlin blue from animal materials, used a rose blossom infusion as an indicator of acids and bases, and used burning mirrors to achieve high temperatures.

In 1722 Geoffroy submitted a report to the Academy of Sciences that clarified alchemical frauds. After his death in 1731, his three-volume chemical work was published. Although he refuted the Philosopher's Stone , he still believed that iron could be made artificially from vegetable ashes.

Through the contact of Caspar Neumanns , a student of Georg Ernst Stahl , to the brothers Étienne François and Claude-Joseph Geoffroy, the ideas of the phlogiston entered French science.

literature

- Winfried Pötsch u. a .: Lexicon of important chemists . Harri Deutsch, 1989

- Geoffroy, Étienne François . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . 11th edition. tape 11 : Franciscans - Gibson . London 1910, p. 618 (English, full text [ Wikisource ]).

Web links

- Geoffroy, Étienne François. In: The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. Infoplease(English).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Olivier Lafont, Maryvonne Lafont: Personnalisation des rapports individu-puissance publique, ou Geoffroy et la famille Le Tellier . In: Revue d'Histoire de la Pharmacie . tape 79 , no. 288 , p. 15-23 , doi : 10.3406 / pharm . 1991.3109 (French).

- ↑ Overview of the Académie des sciences in French (PDF; 440 kB)

- ^ Entry on Geoffroy, Etienne Francois (1672–1731) in the archive of the Royal Society , London

- ↑ Gottfried Wilhelm Bischoff: Textbook of Botany. Volume 2, part 2. Schweitzerbart, Stuttgart 1839, p. 499 f., Urn : nbn: de: bvb: 12-bsb11272136-1 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ Jaime Wisniak: Phlogiston: The rise and fall of a theory . In: Indian Journal of Chemical Technology . tape 11 , 2004, p. 732-743 ( niscair.res.in ).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Geoffroy, Étienne François |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French chemist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 13, 1672 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 6, 1731 |

| Place of death | Paris |