83rd Symphony (Haydn)

The Symphony no. 83 in G minor, composed Joseph Haydn in 1785 for a Paris concert series. The work bears the nickname "La Poule" ("The Chicken"), which was not by Haydn.

General

The symphony No. 83 belongs together with the symphonies No. 82 to 87 to the " Paris symphonies ". These are commissioned compositions for the Parisian “Le Concert de la Loge Olympique.” For the history of its genesis, see Symphony No. 82 .

The title “La Poule” (French for “the chicken”) refers to the “cackling” second subject in the first sentence. It does not come from Haydn and was not made in Paris. It appears for the first time in the Haydn directory of the Zürcher Neujahrsblätter from 1831. It was only naturalized in the 1870s.

The symphony shows several striking contrasts, especially in the first two movements, for example the relationship between the first and second theme in the Allegro spiritoso or the sudden changes in timbre in the Andante. These contrasts are sometimes interpreted in terms of irony or parody, with Haydn's parody possibly also referring to his own earlier symphonies (self-parody). Some of these were known to the Parisian public.

Although only about three quarters of the Allegro spiritoso are in G minor, the key of the symphony is usually given as "minor" and not as "major" (similar to some other minor symphonies by Haydn, e.g. No. 34 ) .

“Symphony No. 83, undoubtedly the most eccentric of the 'Paris' Symphonies, is in Voltaire's sense also the most extreme in its wit. While the 'Poule' theme of the first movement is humorous in Michaelis's sens of 'scherzando' (ie pleasing, jovial and entertaining), it assumes the higher status of serious wit or the comic sublime by virtue of its context, its inappropriateness in a G minor movement which is dominanted by the seriousness of the Haydn's Sturm and Drang-like rhetoric. Similary, the dramatic interruptions of the second movement are comic in the context of the following harmonic clichés; the limping unconventional Menuet is humorously clumsy in relation to the graceful dance-like trio; The development section of the finale is witty in its inapproriateness, as the finale as a whole is bizarrely inapt in relation to the first movement. In short, the symphony's spectacular displays of bizarre contrasts are emblematic of the comic sublime, stretching the credulity of the listener to an extens that none fo the other 'Paris' Symphonies do, even in their most audacious moments. "

“Symphony No. 83, undoubtedly the most eccentric of the Paris symphonies, is in Voltaire's sense also the most extreme in its wit. While the 'hen theme' from the first sentence is humorous in Michaeli's sense of 'scherzando' (i.e. pleasant, cheerful and entertaining), it takes on the higher status of serious wit or comic sublimity due to its context or its inappropriateness in a g- Minor movement that is dominated by seriousness in Haydn's Sturm und Drang style. Similarly, the dramatic breaks in the second movement are comical in the context of the harmonic clichés that follow; the limping, unconventional minuet is humorous and awkward compared to the graceful, dancing trio; the implementation in the fourth movement is funny in its inappropriateness [in relation to the rest of the movement], just as the fourth movement is bizarrely inappropriate in relation to the first movement. In short, the spectacular unfolding of bizarre contrasts is symbolic of the comical and sublime, which extends the gullibility of the listener to an extent that no other of the Paris symphonies can match, even in their boldest moments. "

To the music

Instrumentation: flute , two oboes , two bassoons , two horns in G, two violins , viola , cello , double bass and possibly harpsichord . There are different opinions about the involvement of a harpsichord continuo in Haydn's symphonies. A special feature is that there are three different cello parts in the first movement: In addition to the cello part, which doubles the double bass part, a “violoncello obligato” is noted as a separate line in the score; where the voice is divided from bars 97 to 105 (“divisi”).

Performance time: approx. 20-25 minutes (depending on compliance with the prescribed repetitions).

With the terms used here for the sonata form, it should be noted that this scheme was drafted in the first half of the 19th century (see there) and can therefore only be transferred to Symphony No. 83 with restrictions. - The description and structure of the sentences given here is to be understood as a suggestion. Depending on the point of view, other delimitations and interpretations are also possible.

First movement: Allegro spiritoso

G minor / G major, 4/4 time, 193 bars

The movement opens with an energetic and dramatic theme in fortissimo, based on an ascending four-tone motif with accents (motif 1) and a falling movement in dotted rhythm (motif 2). Both motifs, which together form a four-stroke cycle, are repeated somewhat changed, with the second repetition with continuation of the dotted rhythm (tone repetition). The topic then starts again, but now goes seamlessly into the transition section. At first, the two motifs of the theme dominate here (partly superimposed), before the new motif 3 (broken triad upwards from eighths and sixteenths and eighth note movement downwards) appears in the tonic parallel in B major from bar 33 . The voice-leading violins spiral upwards with the motif, only to announce the second theme in a descent of over two octaves.

This (from bar 45, B flat major) consists of a suggested figure of the 1st violin (motif 4), accompanied only by the staccato eighth movement of the 2nd violin. With its simple, cheerful character and the sparse cast, it contrasts strongly with the serious first topic. From bar 52 there is a repetition, now accompanied by the oboe, which plays the note F in dotted rhythm for five bars. This “cackling” figure, which gave the symphony its name, can be thought of as derived from motif 2.

The final group then begins quite abruptly from bar 59 forte, in which, in addition to triplet runs in unison, the dotted rhythm of motif 2 over a striding, descending bass movement in quarters (motif 5, can be interpreted as a reversal of motif 1) is found again. The exposition ends in measure 68.

The implementation (clock 69-129) processed elements from the first and second subject, which modulated and sequenced will occur, as well as in different voices. From bar 83, motif 6 is added to the fact that it can be derived from motif 3, is used as a continuous "counterpart" to motif 1 and changes to motif 3 from bar 109. From motive 3, the flute and first violin only play the unscrewing head from bar 113, accompanied by a counter-vocal line that ascends chromatically in half notes (reminiscent of motive 1) and underlined by an organ point-like A in the bass. Then at the moment of dramatic tension the music unexpectedly breaks off with almost two bars of general pause. Piano start the strings anew with a hesitant chromatic passage and build up the tension anew with motif 1 underlaid by tones. The tension discharges with the beginning of the recapitulation in bar 130.

The recapitulation is structured in a similar way to the exposition, but shortens the transition section: The processing passage of motifs 1 and 2 analogous to bars 21 ff. Is missing, but the key changes with the use of motif 3 (bar 146) to G major. On the second theme, the flute takes over the “cackling” movement, making it sound a little softer. The final group (bars 171 ff.) Is expanded like a coda : In addition to the elements from the exposition, the now no longer threatening first theme and the “cackling movement” have other appearances. Also noteworthy is the fallacy with a fermata on a dominant seventh chord in measure 181. The exposition as well as development and recapitulation are repeated.

The dotted rhythm appearing in the movement is possibly intended as an allusion to the French opera overture, the "cackling" accompaniment of the second theme is reminiscent of a harpsichord piece in G minor by the French composer Jean-Philippe Rameau , which is entitled "La Poule" .

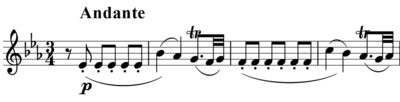

Second movement: Andante

E flat major, 3/4 time, 105 bars

The first theme (main theme), with which the strings open the movement, consists of three motifs: (1) a knocking motif consisting of five-tone repetition, initially with a base bass note, (2) after a fifth upwards a falling line with trills, (3) a slightly chromatic, song-like line with a final trill. Motifs 1 and 2 initially appear alternately (bars 1 to 5), while motifs 3 complete the eight-bar thematic unit (bars 6 to 8). After a brief interjection by the woodwinds, the theme is repeated and continued in a variant decorated with small opposing voices (derived from motif 3) (measure 1 to measure 16).

Then singing, chromatic lines (derived from motif 3) lead in the dialogue of the two violins from C minor to the double dominant F major, which acts as an announcement to the following, “operatic” section in B major. This is characterized by strong contrasts in the timbre: The surprising, gesticulating unison throw-in by the whole orchestra in the form of a unison scale down over two octaves is caught by the tapping tone repetition motif of the main theme, played by the 2nd violin and viola. The anticipated use of the theme then fails to materialize, while the knocking motif continues piano (a total of 22 tone repetitions). The resulting carpet of sound from tone repetition changes its character abruptly in bar 28 through fortissimo tremolo and cadently leads to a suggested motif that continues the previous, downward-moving line. Depending on your point of view, the section from bar 34 with its further suggestion and tone repetition motif as well as the chromatically ascending line can be viewed as a second theme (B flat major, strings only). The final group (bars 41 ff.) Is characterized by a vocal motif of the oboes.

The development (bars 44–72) begins as a continuation of the main theme including minor clouding, which changes from bar 53 to the “operatic” section: starting from the gesticulating throw-in, here as a C major scale up and down, develops by stepping up and down bar by bar a tone a somewhat eerie tone repetition carpet, which leads to a tremolo sound surface in the forte (bars 53 to 60). The strings then continue their vocal dialogue according to measure 17 ff. The section from bars 61 to 72 is imitated with the staggered use of the knocking motif and counter-vocal runs upwards.

The recapitulation (from bar 73) is varied compared to the exposition: the main theme is accompanied with counter-vocal runs upwards in the flute (similar to those at the end of the development), the vocal dialogue of the violins is missing, as is the final section, instead of one there are three of the gesticulating unison scale runs (B flat major, B flat major with seventh, E flat major). The movement ends pianissimo with a staggered entry of motifs 1 and 2 above an organ point on Eb. The exposition, development and recapitulation are repeated.

The abrupt changes in the effects, the harmonic surprises and the dramatic gestures are reminiscent of the shape of the Capriccio or a fantasy (similar to the second movement of Symphony No. 86 ).

Third movement: minuet. Allegretto

G major, 3/4 time, with trio 66 bars

The minuet begins with an upbeat and forte with a song-like pastoral theme, first with a falling line, then with a line rising in unison. The first part of the topic disguises the usual rhythm, as the two eighth notes (third beat) also occur on the first beat. At 34 bars, the second part of the minuet is significantly longer than the first (eight bars). At first he processes the elements of the first part like an implementation, then follows “a kind of mock reprise”: the melody of the theme is unchanged, but due to the organ point on D in the bass and horn (and not on the root G) the listener does not initially have that Impression of being harmoniously back in the G major tonic. The minuet closes with a short coda (bars 35–42), which isolates the upbeat head motif from the beginning of the movement. The emphasis on the second bar with chord strokes reinforces the rhythmic instability of the beginning of the topic.

The trio is more simply structured than the minuet. It is also in G major and is divided into three eight-bar sections. The flute and violin play a peasant melody in continuous staccato eighth notes, some of which is decorated with suggestions.

Fourth movement: Finale. Vivace

G major, 12/8 time, 99 bars

In Vivace, a sentence with a sweeping character and “ oscillating between gigue and chasse”, the thematic work takes a back seat. Instead, a "perpetuum mobile-like movement dominates, in which almost only its rhythm remains of the subject, which is not very profiled anyway, and a grandiose sound massing that replaces the thematic work, especially in the implementation, which is completely focused on harmonic means."

The four-bar main theme is first introduced piano by the strings, then repeated as a variant with the flute leading the voice. From the beginning of the tutti in bar 8, continuous eighth notes, hammering note repetitions, chord melodies and short solos for flute and oboe (e.g. tutti echo after a “bird's voice” of the flute (bar 11 ff.)) Dominate. A final group can be separated from bars 31–34.

The “development” (bars 35–55) begins with the unscrewing initial motif of the main theme and then goes on to a forte block, which is characterized by eighth notes, hammering tone repetitions, accents and numerous key changes.

The recapitulation (bars 55 ff) is structured in a similar way to the exposition, but the flute is used right at the beginning of the main theme. The movement ends with a coda (bar 83 ff.): The rapid movement of the music becomes hesitant through several fermatas and faltering through general pauses. After a final appearance on the main theme, the movement closes with stormy eighth note chains in the forte. The exposition, development and recapitulation are repeated.

See also

Web links, notes

- Recordings and information on Haydn's 83rd Symphony from the “Haydn 100 & 7” project of the Eisenstadt Haydn Festival

- Thread on Symphony No. 83 by Joseph Haydn with a discussion of various recordings

- Wolfgang Marggraf : The Symphonies of Joseph Haydn. - Symphony No. 83, G minor ("La Poule"), accessed on June 6, 2011 (text status: 2009)

- Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 83 g minor (La Poule). Ernst Eulenburg Ltd No. 530, London / Zurich (pocket score, no year)

- Joseph Haydn: Sinfonia No. 83 “La Poule” in G minor. Series: Critical edition of the complete symphonies, edited by HC Robbins-Landon. Philharmonia Universal Edition, No. 783 (pocket score from 1963).

- Symphony No. 83 by Joseph Haydn : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Hiroshi Nakano: Paris Symphony Series 1. In: Joseph Haydn Institute Cologne (Ed.): Joseph Haydn Works. Series 1, Volume 12. G. Henle-Verlag, Munich 1971, 131 pages.

Individual references, comments

- ^ Horst Walter: La poule / The hen / The chicken. In: Armin Raab, Christine Siegert, Wolfram Steinbeck (Hrsg.): The Haydn Lexicon. Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2010, ISBN 978-3-89007-557-0 , p. 602.

- ^ Michael Walter: Haydn's symphonies. A musical factory guide. CH Beck-Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-44813-3

- ^ A b c d e Bernard Harrison: Haydn: The "Paris" Symphonies. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1998, ISBN 0-521-47164-8 , pp. 81-88.

- ↑ Text discussion of the Symphony no. 83 in the project "Haydn 107" of the Haydn Festival Eisenstadt http://www.haydn107.com/index.php?id=2&sym=83 , called 23 May 2009

- ↑ One candidate for this is in particular Symphony No. 39 , which is also in G minor

- ↑ Bernard Harrison refers to the article "The beautiful and sublime in music" by Michaelis from 1805.

- ^ Bernard Harrisson (1998: 87)

- ↑ Examples: a) James Webster: On the Absence of Keyboard Continuo in Haydn's Symphonies. In: Early Music Volume 18 No. 4, 1990, pp. 599-608); b) Hartmut Haenchen : Haydn, Joseph: Haydn's orchestra and the harpsichord question in the early symphonies. Booklet text for the recordings of the early Haydn symphonies. , online (accessed June 26, 2019), to: H. Haenchen: Early Haydn Symphonies , Berlin Classics, 1988–1990, cassette with 18 symphonies; c) Jamie James: He'd Rather Fight Than Use Keyboard In His Haydn Series . In: New York Times , October 2, 1994 (accessed June 25, 2019; showing various positions by Roy Goodman , Christopher Hogwood , HC Robbins Landon and James Webster). Most orchestras with modern instruments currently (as of 2019) do not use a harpsichord continuo. Recordings with harpsichord continuo exist. a. by: Trevor Pinnock ( Sturm und Drang symphonies , archive, 1989/90); Nikolaus Harnoncourt (No. 6-8, Das Alte Werk, 1990); Sigiswald Kuijken (including Paris and London symphonies ; Virgin, 1988-1995); Roy Goodman (e.g. Nos. 1-25, 70-78; Hyperion, 2002).

- ↑ a b c This repetition is not kept in many recordings.

- ↑ Thomas Kahlcke: Complex Inner Life. Joseph Haydn's “Paris” symphonies. Text contribution to the recording of the Paris Symphonies 82–87 with the Academy of St Martin in the Fields with Neville Marriner. Philips Classics Productions, 1993

- ↑ Kahlcke speaks of an "operatic (n) expressive gesture" in the Andante

- ↑ a b c Ludwig Finscher: Joseph Haydn and his time. Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2000, ISBN 3-921518-94-6

- ↑ Jagdstück

- ↑ According to Harrison (1998: 85) the passage is reminiscent of a keyboard instrument fantasy.

- ↑ Some conductors take the entire section at a slower pace.