Polish Home Army

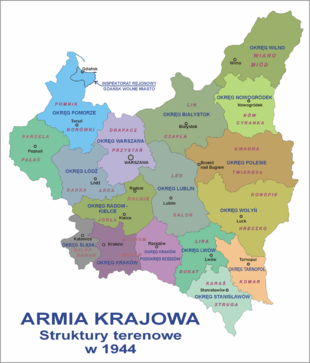

The Armia Krajowa ( Polish for Landesarmee , abbreviated AK ; in German usually referred to as the Polish Home Army ) was a Polish resistance and military organization in Germany-occupied Poland during the Second World War . It was the largest military resistance organization in Europe during World War II. It was an army of volunteers who had set themselves the goal of liberating Poland from the German occupation forces . As the military arm of the Polish underground state, it was subordinate to the “Government Representation in the Country” ( Delegatura Rządu na Kraj ), a department of the Polish government- in- exile in London . In 1944 it had over 350,000 partisans. After the invasion of the Red Army , it continued its unofficial resistance - now against the communist regime. Over 20,000 Home Army partisans were murdered by the communist rulers.

history

It was originally founded in September 1939 as Służba Zwycięstwu Polski (Service for the Victory of Poland). Already in December of the same year it was renamed Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Association for the Armed Struggle), from which the Armia Krajowa emerged in February 1942.

The Armia Krajowa claimed exclusive leadership of the military resistance and endeavored to subordinate all resistance groups that had arisen in occupied Poland to their command. It joined:

- the military organization of the National Democrats : Narodowa Organizacja Wojskowa - from 1942 (partially)

- the peasant battalions of the peasant party : Bataliony Chłopskie - from 1943 (partially)

- the Socialist Party militias : Gwardia Ludowa WRN - from 1942

- the units of the National Radical Camp : Konfederacja Narodu - from August 1943

- the armed forces of the nationalists : Narodowe Siły Zbrojne - from 1944 (partially)

and many smaller groups. The officer corps of the Home Army consisted mainly of former officers of the Polish prewar army .

Outside the structures of the Polish underground state, only the extreme organizations remained, i. H. the National Armed Forces (NSZ) as well as the communists of the Polish Workers' Party ( Polska Partia Robotnicza ) and their People's Guard ( Gwardia Ludowa ) formed from summer 1942 , which did not recognize the constitutional government in exile, was dependent on the USSR and represented its interests. When, after the death of the exile prime minister Sikorski and the arrest of AK commander General Rowecki in the summer of 1943, the balance of power in London shifted and the right-wing NSZ began an underground civil war against the People's Guard, parts of the AK also took part. The AK leadership pushed the political polarization of the resistance, especially the activities of the AK's Anti-Communist Committee (Antyk) formed in 1943 .

Main points of resistance

The AK's main focus was on sabotage warfare and intelligence for the UK Special Operations Executive , SOE. Since the defeat of France and the smashing of the first partisan unit under Major Henryk Dobrzański (“Hubal”) in April 1940 , she refused armed struggle , stood “with rifle at her feet” and instead sought a national uprising. When, however, from November 1942 the peasant battalions began the armed struggle against the mass evacuation of Aktion Zamość and against the ethnic German settlers organized in the SS Landwacht Zamosc , in view of this strong resistance from 1943 the leadership of the AK was ready to set up partisan detachments in the Zamość area .

The units subordinate to the Home Army have in the period from January 1, 1941 to June 30, 1944 in the context of combat operations u. a. 732 trains derailed, almost 40 railway bridges blown up, 19,000 wagons and around 6,900 locomotives damaged, around 4,300 vehicles destroyed, around 25,000 acts of sabotage carried out in armaments factories, 130 arms and equipment stores and 1,200 tankers set on fire, 5 oil towers destroyed, 3 blast furnaces shut down , carried out around 5700 attacks on functionaries of various police formations, soldiers and ethnic Germans, fought over 170 battles and killed over a thousand Germans and freed prisoners from 16 prisons.

The most spectacular actions of the Home Army included a. the closure of the Warsaw railway junction (October 7–8, 1942), the liberation of the prisoners in Pińsk (January 18, 1943), the bomb attack on the Friedrichstrasse S-Bahn station in Berlin (February 15, 1943), the liberation of prisoners in the Center of Warsaw in action at the Arsenal (March 26, 1943) and the attack on Franz Kutschera , the SS and police leader in the Warsaw district (February 1, 1944). By July 1944, around 34,000 soldiers from the Home Army and subordinate units were killed in combat operations, but most were shot as prisoners or tortured to death in prisons.

The armed struggle of the Polish Home Army in 1944

Wehrmacht Operation Sturmwind

The partisan activity of the Home Army increased sharply from the spring of 1944, especially in the Lublin district . With Operation Sturmwind , the Wehrmacht undertook the first large-scale operation from June 8 to 25, 1944 to smash the partisan units. The largest and bloodiest partisan battle on Polish soil took place in the forests of Janów Lubelski . General Siegfried Haenicke put the 154th and 174th Reserve Divisions , parts of the 213rd Security Division , the 1st motorized gendarmerie battalion , the SS against two brigades of the People's Guard, a division of the Home Army and five Soviet partisan divisions with a total of around 5000 partisans -Police regiment 4, the Kalmyk cavalry corps , other units as well as a relay attack aircraft , a total of about 30,000 men. Despite the majority, they did not succeed in smashing the partisan units. They suffered heavy losses.

Operation thunderstorm

The aim of Aktion Burza was the independent liberation of Polish territory by the Home Army.

On July 7, 1944, the Home Army began Operation Ostra Brama , which aimed to liberate Vilnius . The Polish fighters managed to occupy a large part of the city center of Vilnius until Soviet units intervened in the fighting.

From July 22nd to July 27th, the Home Army fighters captured the eastern Polish city of Lviv .

Warsaw Uprising

In early 1944, the Polish Home Army in Warsaw consisted of around 16,000 men. During the Warsaw Uprising from August 1, 1944, the Polish Home Army grew to around 45,000 fighters. The uprising was insufficiently prepared, initially only a tenth of the AK soldiers were armed, and heavy weapons were initially completely lacking. In addition, the uprising largely lacked the support of the Red Army, which had advanced as far as the Vistula .

At the same time as the Warsaw Uprising, the Polish partisans engaged in intense fighting against the retreating Germans in the sections of the front, in which the Red Army and the 1st Polish Army fought for bridgeheads west of the Vistula . The 2nd, 7th and 106th Divisions of the Polish Home Army, which included peasant battalions, and other independently operating larger units took part in these battles.

The uprising was put down by the Wehrmacht , after which Warsaw was extensively destroyed and the Home Army almost completely wiped out. The commander of the uprising, General Bór-Komorowski , capitulated on October 2, 1944 and went with the rest of his troops into German captivity.

From October onwards, the Home Army no longer took part in the fighting of the Polish partisans in autumn 1944.

After the Red Army marched in

The Home Army troops were disarmed by the NKVD , and many of their officers were shot or sent to the Gulag . Those who did not allow themselves to be disarmed continued their struggle in the various new resistance movements. They were referred to as exiled soldiers .

Commander in Chief

- 1942–1943 General Stefan Rowecki (pseudonyms "Grot", "Guemp Schimper")

- 1943–1944 General Tadeusz Komorowski ("Bór")

- 1944–1945 General Leopold Okulicki ("Niedźwiadek").

Prominent members

- Stefan Rowecki (1895–1944), leader of the Home Army

- Adam Borys (1909–1986), founder of the "Parasol" battalion

- Witold Pilecki (1901-1948)

- Elżbieta Zawacka (1909–2009), the only woman who was active as a parachutist for the AK during the war, co-founder of the Archiwum i Muzeum Pomorskie Armii Krajowej Museum in Toruń

See also

literature

-

Bernhard Chiari (ed.): The Polish Home Army. History and myth of Armia Krajowa since World War II. Contributions to military history 57. Oldenbourg, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-486-56715-2 .

- Review by Andreas Mix on H-Soz-u-Kult , August 25, 2003

- Wolfgang Jacobmeyer: Home and Exile. The beginnings of the Polish underground movement in World War II. Leibniz-Verlag, Hamburg 1973, ISBN 3-87473-006-9 .

- Julian Eugeniusz Kulski: Dying we live. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York 1979, ISBN 0-03-040901-2 .

- Timothy Snyder : The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. Yale University Press, New Haven [among others] 2003, ISBN 0-300-09569-4 .

- ders .: Sketches from a Secret War - A Polish Artists Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine. Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2005, ISBN 0-300-10670-X .

- Bernhard Chiari (ed.), Jerzy Kochanowsky: The Polish Home Army: History and Myth of the Armia Krajowa since the Second World War. Oldenbourg 2003, ISBN 978-3-486-56715-1 . MGFA series of publications (Volume 57)

Web links

- The underground army in occupied Poland. on the website The Poles in Battles of the Second World War of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland, 2005

- The Polish Home Army 1939–1945. Site of the Former Home Army Soldiers Section London

- Warsaw Uprising Museum website (with English version; only organizational information in German)

- Home Army and Warsaw Uprising by Tadeusz Pełczynski on the website of the Muzeum Armii Krajowej in Krakow

- Website of the Archiwum Pomorskie Armii Krajowej / Pomeranian Archive of Armia Krajowa (Polish; with English and German links)

Footnotes

- ^ Poles under German Occupation . Institute for National Remembrance . Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- ^ A b c Marek Ney-Krwawicz: The Polish Underground State and the Home Army . Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ↑ Wielkie polowanie: Prześladowania akowców w Polsce Ludowej. The great hunt: persecution of AK soldiers in the People's Republic of Poland. In: Rzeczpospolita. October 2, 2004, accessed March 21, 2018 (Polish).

- ^ The activity of the political parties in the occupied country . Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ↑ a b The Stalinist plan to destroy the pro-western, democratic forces in Poland . Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ Federal Archives (Ed.): Europe under the swastika. Volume 8. Hüthig, Heidelberg 1996, ISBN 3-7785-2338-4 , pp. 179f.

- ^ Federal Archives (Ed.): Europe under the swastika. The occupation policy of German fascism (1938–1945). Volume 8. Hüthig, Heidelberg 1996, ISBN 3-7785-2338-4 , p. 180f., P. 191f.

- ↑ a b c The underground army in occupied Poland . Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ↑ Dramas under the earth . THE WORLD. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ^ Federal Archives (Ed.): Europe under the swastika. Volume 8. Hüthig, Heidelberg 1996, ISBN 3-7785-2338-4 , p. 195.

- ^ Federal Archives (Ed.): Europe under the swastika. Volume 8. Hüthig, Heidelberg 1996, ISBN 3-7785-2338-4 , p. 214.

- ↑ The United States' Policy Toward the Soviet Union 1941–1945 and its Consequences for Poland . Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ↑ Table of Contents / Authors