Eclogae

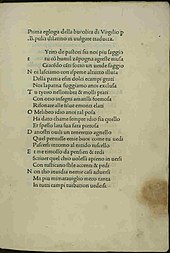

The Eclogues (Latin Eclogae or Bucolica ) are a collection of ten pastoral poems by Virgil , which were probably written between 42 and 39 BC. Was created. Although ancient commentators also assumed this publication period, according to more recent research a date up to 35 BC is also possible. BC conceivable.

The pastoral poems were called Bucolica until the third century , this was probably the original title. The name “ Eclogae ” for Virgil's bucolic poetry, first attested in the 4th century, is certainly not authentic, but has established itself over time.

The formal model of the Eclogae are the idylls (Greek: Eidyllia) of the Hellenistic poet Theocrit from Syracuse (beginning of the 3rd century BC ). Virgil adopts the basic theme of the singing shepherds, but gives the bucolic genre a great deal of depth by incorporating themes from contemporary history and real human emotions, and by significantly reducing the grotesque and humorous. He also pays homage to his patrons Octavian , Alfenus Varus , Cornelius Gallus and Gaius Asinius Pollio .

The historical background, especially of the first and ninth eclogues, is the distribution of land in Cremona and Mantua to 200,000 veterans of the triumvirs as a result of the turmoil of civil war after the events of Philippi and Perusia (42 and 41 BC): many farmers were driven from their lands or left necessarily their country. Virgil was probably also affected at first, but got his property back through the work of Gaius Asinius Pollio and Alfenus Varus with Octavian.

The most famous eclogue is the 4th eclogue , dedicated to Pollio , which dates from approx. 40 BC. BC . In this poem the birth of a world savior and the beginning of a new, golden age is prophesied, which the Christian interpretation interpreted as the announcement of the birth of Christ. This gave Virgil his reputation as an anima naturaliter christiana , as a “naturally Christian soul”, which made him one of the most influential authors on the Middle Ages and the early modern period, despite his pre-Christian beliefs.

Content and interpretation

Eclogue 1: Meliboeus. Tityrus (dialogical)

The first poem of the ten eclogues consists of a dialogue between two shepherds, Tityrus and Meliboeus, against the background of a rural scene. While Meliboeus complains that he is no longer allowed to graze his flocks on the usual land, Tityrus reports that he met a young man ( iuvenem ) in Rome , whom he also calls a deity ( deus ) and who left him his usual pastureland have.

Since late antiquity, the person of Tityrus has been interpreted time and again as Virgil's alter ego and the young man whom Tityrus met in Rome as Octavian. It is controversial whether and to what extent such an allegorical interpretation, already practiced in antiquity (not only the 1st eclogue), which sees masking of biographical and historical events in the typologies of the bucolic world, is permissible. In contrast to the idylls of Theocrit, especially compared to the 1st idyll, the idyllic is pushed out more and more, instead the historical-political world protrudes more and more (allusion to the land distribution). This leads to a historicization of bucolic poetry, which is immediately indicated in the first eclogue, which gives an outlook on the book.

Eclogue 2: Alexis (monological)

Corydon, a shepherd with his own flock, falls in love with the young shepherd Alexis, his master's darling, who, however, rejects him despite all efforts and promises. Corydon tries to gloss over Alexis' life in the country by extolling its advantages, e.g. B. that he has 1000 lambs and therefore fresh milk all year round. He also promises Alexis that he will be able to learn to play the reed flute with him (v. 31: mecum una in silvis imitabere Pana canendo ). In v. 56 ( Rusticus es, Corydon; nec munera curat Alexis ), however, Corydon himself sees that Alexis has absolutely no interest in these things. So in the end (v. 69ff) he only has the lament and the hope for a "different Alexis" if he disdains him (v. 73: invenies alium, si te hic fastidit, Alexin ).

The 2nd Eclogue borrows heavily from Theokrit, v. a. at its 11th Idyll, where the Cyclops Polyphemus woos the nymph Galateia in a similar way . However, here the focus is different, the love agony is serious, there is no self-mocking smile at the scene. In addition, there are explicit elements of Roman love elegance , such as: B. the topos of the Paraclausithyron , but also the lover's distance from reality, which can be recognized by the fact that he wants to offer Alexis a bouquet of flowers, all of which bloom at different times of the year. Thus, this eclogue could have served as a direct model for the later love eligists.

Eclogue 3: Menalcas. Daemoetas. Palaemon (dialogical)

The 3rd eclogue is a contest between the shepherds of Menalcas and Damoetas. Damoetas initially accuses Menalcas of having broken Daphnis' arrows out of jealousy, whereupon Menalcas replies that Damoetas stole a goat from Damon. As a result of these mutual accusations, the shepherds decide to fight their quarrel with a contest, for which Damoetas sets a young cow, Menalca's elaborately carved beechwood cups. Damoetas does not want to accept this, but there is still a competition. The randomly appearing Palaemon is designated as the referee. From vv. 60-107 the two shepherds duel in a distichomythical manner in two verses each, in which the central theme is love. The contrast between homosexual and heterosexual love is also discussed. In the end, Palaemon declared both winners due to the high quality of the singing.

The 3rd eclogue, with 111 verses, is the longest of the first half of the eclogue book. Here, too, there are massive borrowings from Theocritus , especially in the 5th (and partly also in the 4th) idyll. The decisive difference with Virgil is that the rustic and the insults are pushed back. In Theocritus, for example, there is a victor who openly expresses his joy at the victory. The love theme, which had already begun in Eclogue 2, is continued in the competition song, albeit in a somewhat more concise form.

Eclogue 4: The Divine Boy (monological)

The 4th Eclogue is about a prophecy from the Sibylline Books . It is the birth of a divine boy under the consulate of Asinius Pollio in the year 40 BC. Announced that the reign of Saturn would return and the iron age would give way to the golden (vv. 8–9: quo ferrea primum | desinet ac toto surget gens aurea mundo ). There is also talk of peace among humans and animals. In addition, everything grows by itself in this golden age, so that agriculture becomes superfluous (this was a great hardship in ancient times). Trade and economy would also disappear and people could live in a paradise-like state. This golden age is not only associated with the birth of the child, but also matures with it in the course of the text.

The Eclogue (like the sixth) differs massively from the others. The bucolic world does provide suggestions for images here (e.g. the myricae (tamarisks) appear as typical bucolic plants in v. 2 ), but the content and moods are different. The theme of love and also the lament play no role in this eclogue, the bucolic only forms the framework. The whole eclogue is pervaded by a mood of hope for a better time, which begins with the birth of the boy. In research this boy is often equated with Augustus . Manfred Erren, on the other hand, considers the whole poem to be a rather cheeky joke by Virgil. Already in late antiquity, however, a Christian reinterpretation of the text began, since the boy was equated with Jesus Christ . This equation goes back to Emperor Constantine I. It was influenced by a Greek translation of the fourth eclogue that was available to the Council of Nicaea . The translation is very different from Virgil's Eclogue. There are missing z. B. all names of gods, except for those that have purely artistic connotations ( muses ) or are depicted as inferior in the fourth eclogue ( pan ). Historical references such as the Consulate of Pollio are also missing. Much of Virgil's fame in the Middle Ages is based on this interpretation.

Eclogue 5: Daphnis (dialogical)

Like the 3rd eclogue, the 5th is also a song of competition. In this case two shepherds, the young Mopsus and the older Menalcas, sing about the death and the subsequent apotheosis of Daphnis . Both singers present their song about Daphnis in a longer passage (25 verses on both sides). Mopsus begins and describes how much not only the nymphs and the animals would have mourned the death of Daphnis, but also the whole of nature by only sprouting plants that are unusable or dangerous for humans, such as vertigo oats and thorn bushes. Menalcas praises the song of Mopsus and announces his own with the words that he would raise Daphnis to the stars ( Daphninque tuum tollemus ad astra , v. 51). His song is about peace among humans and animals, because Daphnis loves them ( amat bonus otia Daphnis , v. 61). The whole of nature announces his deification ( deus, deus unbekannt, Menalca ! , v. 64) and both humans and animals would worship him forever with sacrifices and prayers. Then the two shepherds Mopsus and Menalcas give each other presents. Mopsus receives a flute made of hemlock stalks, Menalcas an ore-studded shepherd's staff.

The 5th eclogue, as a death poem, is the exact opposite of the 4th eclogue, the birth poem. However, it is permeated by a consistently friendly atmosphere. The competition between the shepherds is not aimed at a winner, but at singing and praising the deceased Daphnis. The focus is not on dying, but on the situation after death. It is shown that the living succeed the dead, which is why death is not represented here as the end, but as the source of life and culture. A political interpretation of the poem was often made, especially in older research, by equating Daphnis with Caesar, who was murdered shortly before . However, this cannot be proven due to the textual basis. More obvious is a poetological interpretation that would fit well at the end of Part 1, where the two shepherds reflect on the value of their poetry. The items exchanged could also represent a form of ritual between poets. However, with regard to this possibility of interpretation, it can also be stated that the symbolism is present, but it is also not without difficulties, so that a clear interpretation cannot be found.

Eclogue 6: The Silenus (monological)

The 6th Eclogue begins before the action begins with a dedication to Varus. It is said that the two boys Chromis and Mnasyllos and the Naiad Aegle found Silenus completely drunk in his cave. Because the Silenus had often promised them a song before, but never kept it, they tie him up with the wreaths that slipped off his head in his sleep. Aegle also paints his face with mulberries. He wakes up, but is not angry, but sings the promised song. This is initially about the creation of the world, the golden age under the god Saturn, Prometheus and the voyage of the Argonauts , so it initially has the features of an educational poem . Then it is about the omnipotence of love with the examples of Pasiphaë and the daughters of Proetus, who mistakenly thought they were cows. The fast runner Atalante and Phaëthon's sisters are also mentioned. The next section of the song then moves away from mythology to the consecration of the Muses of Gallus in Boeotia . The song ends with mythical examples of Scylla as well as Tereus and Procne . The Eclogue ends with evening falling and the valleys echoing with the sound of the Silenian song.

The 6th Eclogue is the only one that has no reference to Theocritus , but to the prologue of Aitien by Callimachus . As is so often the case with Virgil, the bucolic world is given a historical framework by making specific reference to the historical figures Varus and Gallus. The eclogue is diverse in terms of the motifs used. There are death and mourning as well as bondage, but also love in its various forms, each divided into episodes. The theme of the captus amore could even be largely maintained. The motif of the game is always present, both on the content and on the narrative level. Not only do several motifs play into one another , but also several genres such as didactic poems and love strategies. The subject of poetology , which stands out particularly in the Gallus episode, does the rest with the many interwoven motifs to emphasize the real achievement of the poet. This consists in temporarily leading nature out of its paralysis with the help of his poem or song, which can be recognized by the fact that all nature, both plants and animals, begin to dance wildly at the beginning of the song (vv. 27-28) .

Eclogue 7: Meliboeus. Corydon. Thyrsis (dialogical)

Like the 3rd and 5th Eclogues, this one is also about a poetry contest. Meliboeus holds the first and last part of the speech, otherwise Corydon and Thyrsis always speak alternately. At the beginning Meliboeus describes how he came to Daphnis and the Arcadians Corydon and Thyrsis, who had settled under a holm oak because Meliboeus billy goat got lost there. He is invited by Daphnis to attend the poetry contest between Corydon and Thyrsis. These speak alternately with four verses each. The two shepherds attack each other personally ( invidia rumpantur ut ilia Codro , v. 26). The content is about invoking various deities, e.g. B. the nymphs , Priaps and Galateas . In addition, the beautiful Alexis from the 2nd Eclogue is taken up again, after whose departure from nature even the rivers dried up ( at si formosus Alexis | montibus his abeat, videas et flumina sicca , v. 55 f.). The predominant theme, however, is love. At the end of their contest, Corydon and Thyrsis wish that Phyllis and Lycidas would join them. The last two verses are again from Meliboeus, in which he says that Corydon won the competition and since then Corydon has been for him ( Haec memini, et victum frustra contendere Thyrsin | ex illo Corydon Corydon est tempore nobis , v. 69 ff.) .

The 7th Eclogue is (like the 3rd and 5th) a further variation on the theme of competition song, which the narrator Meliboeus reports to the reader from a retrospective. But while in the 3rd eclogue the competition ended in a draw and in the 5th eclogue there was a friendly, even loving atmosphere, the tone here becomes rougher and insults take place on a personal level. Thyrsis embodies the gripping, possessive poet, while Corydon represents the witty and loving poet from self-knowledge. What's also new is that there is a clear winner in the end. In addition, the Arcadian theme is heard, which will play an important role especially in the 10th Eclogue.

Eclogue 8: Damon. Alphesiboeus (dialogical)

The 8th Eclogue is also dialogical, but it is not directly a competition song, as one was used to from the Eclogues up to now. Instead, both Damon and Alphesiboeus speak only once, but each in a coherent piece. The theme of their song is love. After the eclogue has been dedicated to Pollio by a narrator , Damon starts singing. In his poem there are several interludes that are structured by a versus intercalaris (a recurring verse, which in Damon's song reads Incipe Maenalios mecum, mea tibia, versus = "Voice, my flute, with me the songs from Maenalus "). So a lover curses Cupid because he has taken his lover out of him. Medea is cited as a mythological example of its supposed cruelty . In the end, the beloved falls to his death from heartache. The song of Alphesiboeus has a parallel structure, the versus intercalaris here is Ducite ab urbe domum, mea carmina, ducite Daphnin = " Take Daphnis, my songs, take him home from the city." There the narrator slips into the role of the one in Daphnis amaryllis in love. But since he is in town, she uses a love spell to bring him back, which the versus intercalaris already suggests. However, while she is still performing the ritual, Daphnis returns.

The two chants are a typical case of role poetry , as the respective singer slips into the role of another person. The topic of love is illuminated from both a male and a female perspective, with the fulfilled and the unfulfilled in opposition to each other. However, the mythological examples used are negative. It turns out that the characters assume the power of spells. While Damon despairs, Amaryllis is ultimately successful when Daphnis returns home before the rite is performed. The sudden flare up of the ashes, however, stands for the spontaneous and arbitrary of such sayings, which can therefore be described as largely independent of the intention of the speaker. The 8th Eclogue, with 108 verses, is the longest in the second part of the Eclogue.

Eclogue 9: Lycidas. Moeris (dialogical)

The main topic of the 9th Eclogue is the distribution of land. It starts “medias in res” when the two shepherds Lycidas and Moeris talk about this topic. Moeris complains that he was driven from his land by a new owner ( diceret: 'haec mea sunt; veteres migrate coloni', v. 4). Not even Menalcas was able to save the land for the shepherds with his songs, and if a crow had not warned him against resistance, he would no longer be alive (v. 15 f). Lycidas wonders who should then take care of the singing of the nymphs and other typical bucolic shepherd activities. Moeris adds that even the song of praise to Varus can no longer be completed. At the same time he expresses the wish that at least Mantua be preserved for them . After a few verses about their seals Lycidas mentioned in connection with Daphnis the star Caesars ( Caesaris astrum , V. 47). The eclogue ends with Moeris saying that he has forgotten many songs because of his age, while Lycidas suggests singing songs on the way into town, which Moeris rejects.

In the 9th Eclogue it becomes clear like in no other that the bucolic world is under pressure from outside influences. Through this the shepherds are forced to give up their idyllic life. Personal ties are lost and even music becomes a victim of the circumstances, as it is no longer able to stop the breakup of the bucolic world through its effects. In this eclogue, Virgil also deals with real events, since the land distributions also took place around this time. References to the (later) 1st eclogue can be systematically established, where these are also discussed. Virgil thus becomes the spokesman for many people of his time. Strong references can be found to Theokrits Idyll 7 (The Harvest Festival, a "biographical idyll"), but this is turned into negative. The only element of hope that can be interpreted is the Caesaris astrum : It is not enough that poetry can carry someone to the stars, Caesar created a new star that Daphnis can look to with hope. Nevertheless, the 9th Eclogue represents the low point of the Eclogue Book, as it expresses the deep hopelessness that the bucolic world can withstand the pressure from outside.

Eclogue 10: Gallus (monological)

The 10th and final eclogue begins with the presentation of the theme: Gallus' unhappy love ( sollicitos Galli dicamus amores , v. 6). These are weeping from all of nature. Menalcas and Apollon appear and the god announces to Gallus that his beloved Lycoris has followed another soldier ( tua cura Lycoris | perque nives alium perque horrida castra secuta est , vv. 22-23). Pan also reminds him of the cruelty of the love god Cupid . Gallus then complains of his love affliction, although he nevertheless wishes Lycoris not to harm her while she goes away with another soldier. He speaks of wanting to endure his suffering in nature. Nevertheless, neither these nor songs want to please him anymore and he is desperate not to be able to change Cupid's mind. His lament culminates in the saying omnia vincit Amor: et nos cedamus Amori (Cupid conquers everything, so we too want to submit to Cupid, v. 69). The eclogue, and with it the work, ends when the narrator asks the muses to make these verses precious to Gallus and then sends the goats home because it is evening.

The 10th Eclogue is located in the Arcadia landscape , which is very remote and whose inhabitants were considered to be rough pastoralists. But already in antiquity the landscape was transfigured into the place of the Golden Age , a place of human and animal peace, where people, animals, plants and the gods come together - an event that happened the last time at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis had given. The unhappily in love soldier and poet Gallus now enters this world and cannot find his way around the bucolic world at all. This is because love is a vital power for him that he cannot escape. Love is also important for the shepherds, but for them it is only one point among many and life goes on even after an unsuccessful love (cf. Eclogue 2, v. 73: invenies alium, si te hic fastidit, Alexin ) . With the famous verse omnia vincit Amor: et nos cedamus Amori , Virgil also brings the genus bucolic to an end, since the subject of the elegy is now explicitly addressed. From this there are already many motifs and topoi in this eclogue, e.g. B. the Paraklausithyron , the servitium amoris (love as slave service) and the dura puella (the hard-hearted girl). But typical bucolic elements such as self-deception and an unreliable narrator also occur. Thus, this last poem stands, typical of the genre, on the border between bucolic and love elegance.

Editions and translations

- Roger AB Mynors (Ed.): P. Vergili Maronis Opera. Clarendon, Oxford 1969 (critical edition).

- P. Vergilius Maro: Bucolica. Pastoral poems. Latin / German. Translation, notes, interpretive commentary and afterword by Michael von Albrecht . Reclam, Stuttgart 2001.

literature

- Robert Coleman (Ed.): Eclogues. University Press, Cambridge 1977 (comment).

- Bruno Snell : Arcadia. Discovery of a spiritual landscape. In: Bruno Snell: The discovery of the mind. Claassen & Goverts, Hamburg 1949 a. ö.

- Friedrich Klingner : Virgil. Bucolica, Georgica, Aeneid. Artemis, Zurich [u. a.] 1967.

- Ernst A. Schmidt : Poetic reflection. Virgil's bucolic. Fink, Munich 1972.

- Michael von Albrecht : Virgil. An introduction. Bucolica, Georgica, Aeneid. Winter, Heidelberg 2006.

- Manfred Erren : Virgil's prophecy. P. Vergilii Maronis Eclogam IV silvas consule Pollio dignas notis explicui Manfred Erren professor Friburgensis emeritus anno Domini MMXIII ( blog, March 2014) .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ EA Schmidt: On the chronology of Virgil's eclogues. Heidelberg 1974.

- ^ M. von Albrecht: Virgil. Bucolica. Pastoral poems. Reclam, Stuttgart 2001, p. 268.

- ↑ See Nicholas Horsfall: Some problems of titulature in Roman literary history. In: University of London, Institute of Classical Studies: Bulletin. (BICS) 28, 1981, pp. 103-114, here: 108 f .; Heathcote William Garrod: Varus and Varius. In: The Classical Quarterly . 10, 1916, pp. 206-221, here: 218-221.

- ↑ P. VERGILI MARONIS ECLOGA QVARTA ( Latin ) THE LATIN LIBRARY. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ↑ See Erren: Virgil's prophecy.

- ↑ Cf. M. von Albrecht: Virgil. Bucolica. P. 136 ff.

- ↑ See Michael von Albrecht, 2001, p. 149 f.

- ↑ See Michael von Albrecht, 2001, p. 187.

- ↑ See Michael von Albrecht, 2001, p. 198.

- ↑ See Michael von Albrecht, 2006, p. 57.

- ↑ See Michael von Albrecht, 2001, p. 206.