Color TV game

| Color TV game series | ||

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Nintendo , Mitsubishi | |

| Type | Series of stationary game consoles | |

| publication |

|

|

| Storage media | no | |

| Online service | none | |

| Units sold | unclear: approx. 1.5 million or approx. 3 million | |

| predecessor | none | |

| successor | Famicom and Game & Watch consoles | |

The Color TV-Game series ( Japanese カ ラ ー テ レ ビ ゲ ー ム , Karā Terebi Gēmu ) comprises the first five stationary game consoles from Nintendo, which later became the world market leader in the video game industry . The devices published in Japan between June 1, 1977 and the end of 1980 belong to the first generation of game consoles , ie the games contained are inseparably connected to the device by hard-wired logic and cannot be replaced by additional game modules . The designation color refers to the ability - in contrast to many other game consoles of the time - to be able to output colored graphics on the connected television.

The first two consoles in the series, Color TV-Game 6 and Color TV-Game 15, are adaptations of the pong game that was widespread at the time . They were developed in cooperation with Mitsubishi Electric and came onto the market on June 1, 1977. The two devices set themselves apart from the competition due to their low price of 48,000 yen, among other things, and their numerous sales enabled Nintendo to rise to become the market leader in the Japanese home console market. In 1978 the racing game console Color TV-Game Racing 112 followed and in 1979 the breakout adaptation Color TV-Game Block Kuzushi. The last device in the series appeared in 1980, the Othello - Simulation Computer TV Game.

There are various statements about the sales figures for the series: David Sheff states that around three million units have been sold, while Florent Gorges' later research shows that only around 1.5 million units were sold.

background

As a result of the 1973 oil crisis , Nintendo's business with laser shooting simulations ( Laser Clay Shooting System ) collapsed. Since this was the most successful business of the manufacturer of Hanafuda playing cards and toys, which had been in existence since 1889 , the group was facing a major crisis. From 1975 onwards, Group President Hiroshi Yamauchi (1927–2013) developed an interest in the video games market. As a result, Nintendo launched its first arcade machines in the following years . Yamauchi also observed the home video game console business built mainly by Atari and Magnavox in the West. In Japan, the first home console hit the market on September 13, 1975, the TV Tennis Electrotennis from Epoch-sha .

Color TV game

History of origin

In order to be able to publish its own home console and thus become part of the new market, Yamauchi licensed the concept of the Magnavox Odyssey in 1977 , which appeared in 1972 as the first commercial home console. Since Nintendo could not produce the required technology itself, cooperation with an electronics company was necessary. Therefore Nintendo entered into a cooperation with Mitsubishi Electric for the project .

Mitsubishi had approached Nintendo about their own home console project. Due to tough competition in the pocket calculator industry, Mitsubishi turned to other sectors of the electronics market in the second half of the 1970s and started a console project, among other things. For this, the group had worked with a company called Systek. Due to its imminent bankruptcy, the project could not be completed.

Yamauchi transferred the management of the joint console project between Nintendo and Mitsubishi to the engineer Masayuki Uemura (* 1943) who had previously worked at Sharp . Hiromitsu Yagi was involved as the supervisor of Mitsubishi. Nintendo took over the design and sales of the console, while Mitsubishi was responsible for the production of the integrated circuit that represented the technology behind the console to be developed.

In order to differentiate itself from the competition in the Japanese home console market at the time, which mostly sold its consoles for over 20,000 yen , Yamauchi was aiming for a retail price of less than 10,000 yen for Nintendo's product. The console had to cost at least 12,000 yen in order for production costs to be brought in again. Therefore, Nintendo decided to offer the console in two versions, which should differ in scope and comfort and thus also in price. The cheaper version should be sold below the targeted price limit and thus below the production costs, the more expensive above the production price and therefore well above the cost limit and thus be profitable for Nintendo.

The technology of the two console variants is identical despite the different number of games. This reduced the manufacturing cost. The integrated circuit that Mitsubishi makes for the two consoles is called M58815P . Later revisions of the two consoles are equipped with the M58816P circuit .

Color TV game 6

The color TV game 6 (カ ラ ー テ レ ビ ゲ ー ム 6 Karā Terebi-Gēmu Roku ) measures 29 cm × 14 cm × 8 cm and contains six games based on the concept of the classic game Pong (Atari, 1972). They are effectively three different games that only offer a two-player mode. Each game is available as a variant with one or two clubs per player, which is how the number of games in the title comes about. The players move their clubs with the help of a control knob on the housing . The console's screen output is in color.

With six LR20 batteries, Color TV-Game 6 offers a running time of around nine hours. The console does not have a power connection.

The Color TV Game 6 was released in June 1977 for 9,800 yen. The original variant (model name CTG-6S) is white; a few weeks later it was revised with an orange housing (CTG-6V) for 5,000 yen. That revision contains a power adapter that is compatible with all color TV game consoles and is the most widespread variant of the color TV game 6.

Special publications by other companies followed. Sharp, for example, sold its own version of the Color TV Game 6 licensed by Nintendo along with its own televisions. In addition, companies such as instant noodle producer House Shanmen offered their own versions of the console in very small numbers for advertising reasons.

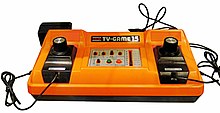

Color TV-Game 15

In addition to the Color TV-Game 6, Nintendo released the extended version of the console, the Color TV-Game 15 (カ ラ ー テ レ ビ ゲ ー ム 15 Karā Terebi-Gēmu Jū-Go ) with 15 games. All six games of Color TV-Game 6 are included; the new games are also variations of Pong . The exception is the shooting game , in which the player has to hit targets with a stick on the other side of the screen. The remaining seven games are only available as a two-player variant with one or two clubs per player.

The Color TV-Game 15 has the dimensions 21 cm × 15 cm × 10 cm and can be operated with LR20 batteries as well as with a separately sold power adapter. In contrast to Color TV-Game 6, the two controllers of the console are wired so that the players can take them in their hands for more comfortable control.

Color TV-Game 15 was published parallel to Color TV-Game 6 in June 1977. It cost 15,000 yen, making it less than twice as expensive as the Color TV Game 6, while containing over twice as many games. Later Nintendo released a revision with an orange and a red housing under the model name CTG-15V. Sharp released a variant with a white housing color. Around Christmas 1978, Nintendo reduced the price of the Color TV Game 15 to 7,500 yen. A little later, the company stopped selling the console.

Sales figures and market success

The sales of the two consoles are controversial. According to the Nintendo historian Florent Gorges from 2010, the Color TV Game 6 sold a total of 360,000 times, making it a great success in the context of the industry at the time. The more expensive variant, on the other hand, is said to have gone over the counter 700,000 times in Japan. In 1993, the journalist David Sheff named sales figures of around one million units each for both consoles. Another piece of information comes from the game journalist Chris Kohler, who wrote in 2004 that both color TV game consoles together were sold over a million times.

Color TV-Game 6 and 15 turned out to be the most successful video game consoles on the Japanese market at the time. With them, Nintendo was able to successfully assert itself against the competition. Nintendo thus dominated about 70% of the Japanese home video game market at the time, while the remaining market shares were held by 20 other companies.

Racing 112 and Block Kuzushi

Development and housing design

Since Nintendo was unable to keep its two consoles up to date by releasing new games due to the lack of module support, their market cycle was short-lived. The success of the two variants of the color TV game was therefore only short-term. To keep it going, Nintendo had to bring new consoles to market. The development of two new color TV game consoles with the titles Racing 112 and Block Kuzushi began. Takehiro Izushi (* 1952) was responsible for the hardware design of the two consoles . Shigeru Miyamoto (* 1952), the later creator of game series such as Super Mario and The Legend of Zelda, was responsible for the housing design . It was the first order for industrial designer Miyamoto, who was hired by Nintendo in 1977. He was dissatisfied with the design of the two previous consoles and aimed for a design for the next consoles that should look more fun. So he insisted on integrating a gear stick for the racing game Racing 112. Miyamoto did not label the switches on the casing of Racing 112, with which the player can set options, but provided them with easy-to-understand symbols. He designed the case of Block Kuzushi in such a way that left and right-handers can enjoy the game equally.

Block Kuzushi was the first color TV game part to be developed independently by Nintendo and without Mitsubishi. Therefore, the Nintendo logo is visible on the top of the console for the first time.

Color TV-Game Racing 112

The third Nintendo console, Color TV-Game Racing 112 ( カ ラ ー テ レ ビ ゲ ー ム レ ー シ ン グ 112 Karā Terebi-Gēmu Rēshingu Hyaku-Jū-Ni ), offers a racing game . The road is shown from a bird's view and without a spatial perspective. The console includes ten game variations with goals such as overtaking as many cars as possible in a certain period of time or driving as far as possible without a collision. The console can display a maximum of four vehicles at the same time. Options such as the number of cars, their speed, the type of road, crash barriers or slipperiness can be set, so that a total of 112 different game modes are included.

In single player mode, a steering wheel integrated into the housing, including a circuit, serves as a control. In addition, the console offers a two-player mode in which only the two included cable controllers, each with a rotary control, can be used for control.

With a size of 47 cm × 17 cm × 26 cm, the color TV game Racing 112 is the largest console ever published by Nintendo. The integrated steering wheel has a diameter of 18 cm.

Originally announced for 18,000 yen, Color TV-Game Racing 112 was finally released in June 1978 for 12,500 yen. In 1979, Nintendo lowered the price of the console to 5,000 yen.

Color TV-Game Block Kuzushi

Color TV-Game Block Kuzushi ( カ ラ ー テ レ ビ ゲ ー ム ブ ロ ッ ク 崩 し Karā Terebi-Gēmu Burokku Kuzushi ) measures 32 cm × 17 cm × 8 cm. The console offers six variants of the game concept behind Breakout (Atari, 1976). Accordingly, the player controls a racket on the lower side of the screen with which he can control a ball. If the ball touches one of the blocks shown in the upper section of the screen, the player receives points and the block that was hit disappears. In the Block Lighter game mode , four blocks are flashing highlighted that the player must hit, while the remaining blocks earn bonus points. In another game mode, Block Trough , all touched blocks disappear and the goal is to make all blocks disappear as quickly as possible. The console enables the player to determine the game variant and the number of balls via switches. In the game, the player can control the racket using a rotary control and thus influence the speed and the rebound angle of the ball.

Block Kuzushi went on sale for 13,500 yen. The period of publication in the secondary literature is given as April 1979. According to a Japanese prospectus, the official release date was March 8, 1979. In 1980 the price of the console was reduced to 8,300 yen and in 1981 it was withdrawn from the market.

Sales figures

According to Gorges, Nintendo sold about 160,000 units of Racing 112, while Block Kuzushi in Japan was sold over 400,000 times, according to the Japanese Toy Journal in 1979, despite strong competition from Atari and Epoch-sha . According to David Sheff, Racing 112 and Block Kuzushi each sold half a million times.

Computer TV game

Computer TV-Game (コ ン ピ ュ ー タ ー TV ゲ ー ムKonpyūtā Terebi-Gēmu ) is the last of the early Nintendo consoles and was released in early 1980. It is a home replica of Computer Othello (Nintendo, 1978), an arcade game from Nintendo, which itself is an adaptation of the strategic two-person board game Othello . The console does not provide color output.

Computer TV-Game contains the same technology as the arcade machine on which the console is based. This is why it is very large, technically out of date at the time of its publication and relies on a power connection that weighs around two kilograms.

You can either play against a second player or against the computer. One advantage of the console over the arcade version is that the player has unlimited time for a move.

The computer TV game was released in 1980 for 48,000 yen. This contradicted Yamauchi's strategy of bringing consoles out as cheaply as possible, and can be explained by the fact that the console was mainly aimed at companies. These should make computer TV games available to their customers for entertainment or to bridge waiting times. Accordingly, Nintendo released the console in small numbers. It is considered to be the rarest electronic Nintendo product.

reception

criticism

The video game journalist Chris Kohler wrote in 2004 that the consoles of the Color TV-Game series showed only a few differences to the competition in terms of content, but that their housing and controller design stood out. According to Kohler, the color of their housing made the consoles clearly look like toys.

Color TV-Game 6 and Color TV-Game 15 convinced the Japanese video game market of that time with their good quality, their relatively low price and their color representation. Most competing consoles offered black and white graphics compared to Nintendo's products, were very similar to each other and were relatively more expensive.

The 112 game variants of the Color TV Game Racing 112 were very similar to one another. However, since the console offered an impressive game speed for the time and the controls worked well, it is still considered to be of good quality for play.

Color TV-Game Block Kuzushi distinguishes itself from other breakout clones of the time by its diverse game options . The pace of the ball and the controls are considered successful, some of the included games are original and varied.

Computer TV-Game has been criticized for its unusually high price and low quality in comparison. The artificial intelligence is simple and does not offer the player a great challenge.

Meaning for Nintendo

Thanks to its first home consoles, Nintendo rose to become the leader of the Japanese home video game market and was able to avert the previously threatened bankruptcy. Without expansion options in the form of game modules, however, the color TV game consoles were only short-term successes. Therefore, Nintendo then looked for products that would enable more lasting success.

After the release of the color TV game consoles, Nintendo turned to the arcade and handheld market ( Game & Watch ) within the games sector . The experience gained since then resulted in the 1983 release of the Famicom , a home console with interchangeable game modules that Nintendo manufactured with the support of Ricoh . The Famicom achieved global success under the name Nintendo Entertainment System . The head Mitsubishi technician of the color TV game project, Hiromitsu Yagi, was later responsible for the technology of the Famicom at Ricoh.

Reception through later video games

The Nintendo game Alleyway ( GB , 1989) is based on the gameplay of the color TV game Block Kuzushi. In WarioWare, Inc .: Mega Microgame $! ( GBA , 2003) contains an implementation of Racing 112 in the form of a mini-game and WarioWare : Smooth Moves ( Wii , 2006) has a mini-game based on Color TV-Game 6. Color TV-Game 15 also appears as a so-called helper trophy in Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 3DS / for Wii U ( 3DS / Wii U , 2014).

literature

- Florent Gorges: The History of Nintendo, Volume 1 . 1889–1980: From playing cards to Game & Watch. Pix'N Love, 2010, ISBN 978-2-918272-15-1 , 8: The First Video Game Consoles, pp. 212-225 .

- Chris Kohler: Power Up . How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life. BradyGames, Indianapolis, Indiana 2004, ISBN 0-7440-0424-1 , pp. 30-33 .

- David Sheff: Game Over . How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children. Random House, New York 1993, ISBN 0-679-40469-4 , pp. 26th f .

- Erik Voskuil: Before Mario . The fantastic toys from the video game giant's early days. Omaké Books, 2014, ISBN 978-2-919603-10-7 , 5: Home Consoles, pp. 188-209 .

Web links

- Overview page for the color TV game series , at: Before Mario, from March 15, 2011, English

- Inside Nintendo 56: Color TV-Game - the history of the first Nintendo consoles , at: Nintendo-Online, from December 28, 2014

- Nintendo's First Console Is One You've Never Played , at: Kotaku , from March 25, 2011, English

- Video for Color TV-Game 6 , on YouTube , July 11, 2010, English

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2010, p. 216.

- ↑ a b c d e Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2014, p. 218.

- ↑ a b c Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2010, p. 220.

- ↑ a b brochure for the Color TV Game Block Kuzushi; Access via Erik Voskuil: Nintendo Color TV Game Block Kuzushi - Leaflet. In: Before Mario. January 7, 2012, accessed February 27, 2015 .

- ↑ a b c d e Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2010, p. 224.

- ↑ Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2010, pp. 216, 218, 220, 222.

- ↑ a b c d Sheff, Game Over, 1993, p. 27.

- ↑ 10 Oldest Video Game Consoles in The World. In: Oldest.org. December 4, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2019 (American English).

- ↑ Sheff, Game Over, 1993, p. 26 f.

- ↑ Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2010, p. 212.

- ^ Kohler, Power Up, 2004, p. 30.

- ↑ a b c d e Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2010, p. 214.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Tobias Schmitz: Inside Nintendo 56: Color TV-Game - the history of the first Nintendo consoles. In: Nintendo-Online. December 28, 2014, accessed January 7, 2015 .

- ↑ a b c d Voskuil, Before Mario, 2014, p. 194.

- ↑ Maintenance manual Color TV-Game 15; Access via Erik Voskuil: Nintendo Color TV Game 15 - Service Manual (カ ラ ー テ レ ビ ゲ ー ム 15 サ ー ビ ス マ ニ ュ ア ル). In: Before Mario. December 28, 2011, accessed February 27, 2015 .

- ^ Voskuil, Before Mario, 2014, p. 190.

- ^ Voskuil, Before Mario, 2014, pp. 190, 194.

- ↑ a b Kohler, Power Up, 2004, p. 31.

- ↑ Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2010, p. 216 f.

- ↑ Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2014, p. 217.

- ↑ a b Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2010, p. 218 f.

- ↑ a b Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2010, p. 219.

- ↑ Iwata asks: Game & Watch, 1. When the developers were doing it all. In: Nintendo. April 2010, accessed February 14, 2015 .

- ↑ a b Kohler, Power Up, 2004, p. 32 f.

- ↑ a b c Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2010, p. 223.

- ^ Voskuil, Before Mario, 2014, p. 198.

- ↑ a b c d e Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2010, p. 220 f.

- ^ Kohler, Power Up, 2004, p. 33.

- ↑ a b c Voskuil, Before Mario, 2014, p. 202.

- ↑ a b c d Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2014, p. 222.

- ↑ a b c Voskuil, Before Mario, 2014, p. 206.

- ^ Voskuil, Before Mario, 2014, p. 188.

- ↑ Gorges, The History of Nintendo, 2010, p. 234.