Cunninghamhead Mansion House

Cunninghamhead Mansion House was a country house in Irvine in Scotland administrative unit North Ayrshire . It was built in 1747 and completely destroyed in the early 1960s by a fire that broke out during renovation work. The stables of the house have been preserved and are now used as a private residence. The former gardener's house still exists as a ruin. From 1964 the property was redesigned so that it could be used as a chicken yard. It later became a campsite . Around 2003, this campsite was significantly redesigned so that it now serves as a motorhome parking space for retirees and early retirees.

History of the Cunninghamhead Estate

The former name of the site was "Woodhead"; the name change to "Cunninghamhead" took place before 1418. A charter from 1346, drawn up by King David II , for Godfrey de Ross calls this "of Coyninghamheid". In the early 15th century, Cunninghamhead fell to the Cunninghame family when Robert Cunninghame married the Douglas heiress to the estate . Since then the head of the family has been called the Laird of Cunninghamhead . Gordon's map from 1654 shows "Cunningham Head" and Moll's map from 1745 shows the area as "Rungham". Cunninghamhead Castle was a square-plan residential tower that Pont called the "strong old keep " and that John Snodgrass had demolished in 1747 when the mansion was being built. The original meaning of "donjon" is mound . The property was bought by John Snodgrass Buchanan on January 23, 1728, at a cost of £ 23,309 2d.

At the time of its construction, the Cunninghamhead Mansion House was one of the most elegant houses in the country. By Robertson's time (1823) it had already lost much of its original elegance. William Aiton's 1811 map of Ayrshire shows the new country house and the ruins of the castle behind it.

The Cunninghame family held the property for several centuries before the Snodgrass family bought it. 1823 were Buchanans of Craigievairn the owners; It belonged to Mr Snodgrass Buchanan in 1838. The Kerrs then followed suit and for 1951 the statistical records show a Mrs Kerr as the owner. Middleton was part of the estate. Around 1564 the name is given as "Cunnygahamehead" and Powkellie , now Polkelly Castle near Stewarton , also belonged to the owner .

The Cunninghamhead Moss was called "Kinnicumheid Moss" in the 18th century; a legend in Ayrshire reports that the Lord of Auchenskeith at Dalry , an evil sorcerer, caused the devil to build a road through Kinnicumhead Moss in just one night. As a result, the original pronunciation of “Cunninghame” was closer to “Kinikam”.

Sir William and Sir John Cunninghame

Of the generations of Cunninghames who lived at Cunninghamhead, Sir William and his brother, Sir John, are considered the most important. Sir William was in the Great Parliament from 1560 and was a great supporter of the reforms of John Knox , who saw "the end of poverty" in Scotland as the actual state religion. Sir John was a member of the General Assembly in 1565, which "at that time seemed so offensive to members of the old religion".

The highland swarms

In the 1640s, Alasdair MacColla had been sent by the Marquess of Montrose to suppress support for the Convenant cause. He ransacked the Ayrshire countryside for a few days and then asked for fines. Sir William Cunningham's fine for Cunninghamhead was 1,200 marks , with £ 10,000 damage already caused.

The second "highland swarm" episode, consisting primarily of Catholic Highlanders, came to Ayrshire in 1678 by the Crown Administration to prevent the conventicles or public meetings of the Presbyterians . In Cunninghamhead, which then belonged to William Cunninghame, the Highlanders lived hand to mouth for a month: what they couldn't eat they destroyed, they used fire to open locked rooms and the sergeant of the troops threatened a farmer with to whom he had made quarters so that if he did not hand over his money he would hang him in his own barn.

Robertson states that “they took vacant quarters; they robbed people in the street; they struck down those who complained and wounded them; they stole the cattle and murdered them willfully; they burned people with fire to force them to reveal where they had hidden their money; they threatened to burn houses if their demands were not immediately satisfied; in addition to free boarding and lodging, they asked for money every day; they even forced poor families to buy them brandy and tobacco every day; they cut and wounded people out of sheer devilry. ”In the parishes of Dreghorn and Pearceton alone the cost of all of this was £ 1,505 17s.

The Cuninghames from Towerland

On December 19, 1600, William Cuninghame from Towerlands (near Bourtreehill ) was tried for high treason; his brother, Alexander , along with a group of hired soldiers "seized the house of Cunninghamhead by force in March 1600". The king had issued a written order to them to leave the property, but they turned their guns on the king's commissioners and fired arquebuses at them. Cunninghame was found guilty of assisting his brother and sentenced to be beheaded at the Edinburgh Market Cross. All of his lands and possessions were revoked at the same time.

Residence of the Snodgrass family

John Snodgrass acquired the property in 1728, had the old residential tower demolished in 1747 and the country house built. Neil Snodgrass had the stables built and the country house expanded or remodeled. Neil Snodgrass was scheduled to study law in 1755, but his eyesight was badly damaged by smallpox and he had to return to the country and pursue rural pursuits. He became a good friend of Alexander, Earl of Eglinton , and joined him in his efforts to improve methods of farming such as: B. the crop rotation and the fallow year. In 1773 he married Marian , the daughter of James McNeil Esq. from Kilmirie . They had six children together.

Aiton congratulated Mr. Snowgrass (actually Snodgrass ) in 1811 on his zeal in pursuing agricultural improvements, following the example of the Earls of Eglinton and Loudoun and others. The coat of arms of the Snodgrass family was a judiciary with a scale, their motto: "Discite Justinian". The lands of Cunninghamhead were valued at £ 330 in 1640. William Kerr Esq. von Cunninghamhead was buried in the parish churchyard of Dreghorn .

Mr. and Miss Buchanan of Cunninghamhead competed in the famous Eglinton Tournament (re-enactment of a medieval joust ) in what is now Eglinton Country Park in 1839 . They have been allocated a seat in the Grand Stand .

The Kerr family

Hugh Kerr of Gatend Farm near Barrmill died on August 9, 1818, and his wife died on August 19 of that year. Three of Hugh's sons immigrated to America and became very rich. William Kerr bought Cunninghamhead and resided there in his retirement until his death in 1853. His only descendant, Richard , succeeded him.

The Cunninghamhead Estate today

Cunninghamhead Mansion House

The dilapidated country house was bought by a property developer after the death of the Kerr sisters. The renovation of the house was almost complete when vandals broke in and set it on fire. The fire occurred in the early 1960s and the house was damaged too badly to be restored. It was torn down.

Parking space for mobile homes and camping site

In the 1960s, the property was clearly run down; the access road could no longer even be used on foot. From 1964 work was carried out, initially to use the property as a chicken farm and later as a parking space for mobile homes and a campsite. From 2003, major redesigns of the parking space for mobile homes and the campsite were carried out so that there is now a mobile home space exclusively for retirees and early retirees.

Wigwam bar

In the 1980s, a large building for the Wigwam Bar was built on the Cunninghamhead Estate . The bar served as the RV park and had various facilities for the young farmers on site. At the turn of the millennium, the bar building was converted into two holiday apartments.

Cottage Orné

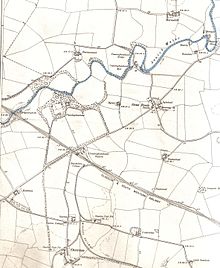

An unusual building of a certain age stands as a large ruin in the floodplain on the south bank of the River Annick Water . A road through the forest connects the ruins with the stables and the location of the former country house. The remains of this building are made of fairly large river stones and heavily edited and hewn sandstone - stone blocks . The ruin has a large door with a window facing the floodplain, while the wall facing the river has largely collapsed; there could have been two large windows in it. The door was carefully walled up and the window facing the floodplain could have been converted into an entrance.

The relatively small size of the plant could indicate a social use, e.g. B. as a summer house or cottage Orné , from the early days of the property, around 1747. The last occupant of the building was a Mackay who was a poet or writer. Charles Mackay was editor of the Glasgow Argus for four years from 1844 ; he then returned to London and joined the Illustrated London News . Another, lesser known Charles Mackay , an actor and writer, belonged to the early 18th century.

Aiton provides the following description of a building on the Eglinton estate that may have inspired the construction of this possible summer home: “Near the garden, in a remote corner, more than half-enclosed by the river, according to the ideas of Lady Montgomery, who has devised a combination of grace and simplicity with fine taste, built and equipped a more than pretty farmhouse. This amiable lady occasionally spends part of her free time with this wonderful farmhouse: looking at the beauty, admiring the natural processes in the foliage, the blossoming of the flowers, the ripening of the fruit; with other sensible conversations that her exalted mind may enjoy. ”Lady Jane Hamilton , the earl's aunt, had Lady Jane's Cottage built or extended on the banks of Lugton Water . She used this building to teach housekeeping to peasant girls. This may have been the later use of Lady Jane's Cottage .

Gardener's house

The gardener's house is at the end of the road to the river. The building was of considerable size and expanded at least once in its history. After continuing vandalism, it was demolished in the 1980s.

stables

The main stables, which once housed the administration offices of the estate, have an impressive main facade dating from 1820; the rest of the stables were probably built in the 1740s. A row of small workers' houses were down in the courtyard, which can still be seen today from the walled-up doors. There are three small pillars in front of the stables that riders could use to mount their horses. These climbing aids were installed by a previous owner of the Cunninghamhead Mansion House and are not original.

A small pigeon house was located above the entrance arch until it was removed by the current owner. This was a detail of many properties as the right to build such a dovecote was originally restricted to the large landowners. Only later were smaller, free farmers allowed to build them as well. Even later, tenants could sometimes obtain permission from their leaseholders to build pigeon houses for meat or other decorations on their property.

The stables were offered for sale from 2008 and sold in mid-2015. Comprehensive renovation plans have been submitted by the new owner.

More ruins on the property

Ruins of other outbuildings, e.g. B. the gardener's house (see above) can be found in the woods on the left side of the path to Annick Water. Quarry Holm, next to the old railway line between the property and Annick Lodge, houses the foundations of some old structures, presumably industrial buildings that were used for other purposes before they were abandoned. The 1843 railroad separates this site from that of Annick Lodge .

Natural history of the property

Parts of the deciduous forest north of Annick Water on the site of the former country house are rich in biodiversity , indicating that they have existed for a long time and are not just plantings on recently developed wasteland. These sparse forests contain plants such as B. the real worm fern , the lady fern , the knot comfrey , the tussock , the hare bell , the forest bingelkraut , the opposite milkweed , the hornbeam , the sanicle , witch's herbs and the wood sorrel . Mints are another uncommon species that grow in the floodplains on the banks of Annick Water, along with wild mint just upstream from the old railway bridge.

Individual evidence

- ^ Ian MacDonald. 2006.

- ↑ The Cunnynghame Family of Cunninghamhead . Webring. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ↑ a b c James D. Dobie, JS Dobie (editor): Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604-1608, with continuations and illustrative notices . John Tweed, Glasgow 1876.

- ^ W. Mackay Mackenzie: The Mediaeval Castle in Scotland . Methuen & Co., London 1927. p. 5.

- ^ Robert Reid of East Balgray & Caldwell: Family Records . Self-published in 1912. p. 167.

- ^ A b c George Robertson: A Genealogical Account of the Principal Families in Ayrshire . A. Constable, Irvine 1823.

- ↑ James Rollie: The invasion of Ayrshire. A Background to the County Families . Famedram, 1980. p. 83.

- ↑ John Service: Thir Notandums, being the literary recreations of the Laird of Canticarl Mongrynen . YJ Pentland, Edinburgh 1890. p. 105.

- ↑ David Stevenson, 'Highland Warrior. Alasdair MacColla and the Civil Wars. The Saltire Society, Edinburgh 1994. ISBN 0-85411-059-3 . P. 205.

- ^ Rev. R. Lawson: Maybole Past and Present. J. & R. Parlane, 1885. p. 49.

- ^ William Robertson: Ayrshire. Its History and Historic Families . Tape. 1 & 2. Ayr 1908.

- ^ William Robertson: Old Ayrshire Days . Stephen & Pollock, Ayr 1905. pp. 299-300.

- ↑ Discover Ayrshire ( Memento of the original from December 15, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Michael C. Davis: The Castles and Mansions of Ayrshire . Spindrift Press, Ardrishaig 1991. p. 228.

- ^ William Aiton: General View of the Agriculture of the County of Ayr . Glasgow 1811. p. 61.

- ^ J. Aikman, W. Gordon: An Account of the Tournament at Eglinton . Edinburgh: Hugh Paton, Carver & Gilder, Edinburgh 1839. p. 8.

- ↑ Gatend, Byre . British Listed Buildings. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ↑ John Ward. 2006. Oral information.

- ^ AH Millar: The Castles & Mansions of Ayrshire . The Grimsay Press, 1885 (reprint). ISBN 1-84530-019-X . P. 74.

- ↑ JFC Peters: Discovering Traditional Farm Buildings . Shire Books, 2003. ISBN 0-85263-556-7 .

Web links

Coordinates: 55 ° 38 ′ 10.6 " N , 4 ° 30 ′ 36.2" W.