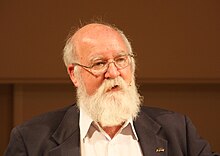

Daniel Dennett

Daniel Clement Dennett (born March 28, 1942 in Boston ) is an American philosopher and is considered to be one of the leading exponents in the philosophy of mind . He is Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Center for Cognitive Science at Tufts University .

Life

In 1963 Daniel Dennett graduated from Harvard with a bachelor's degree in philosophy. He then moved to Oxford to work with the philosopher Gilbert Ryle , where he received his PhD in philosophy in 1965. From 1965 to 1971 he taught at the University of California, Irvine . This was followed by visiting professorships at Harvard, Pittsburgh , Oxford, the École normal supérieure de Paris , the London School of Economics and Political Science and the American University of Beirut . He then went to Tufts University, where he has been teaching ever since.

He has received two Guggenheim Fellowships , a Fulbright Fellowship, and a Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences fellowship.

Dennett is a member of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (elected in 1987). He has been a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science since 2009 .

Dennett lives in North Andover, Massachusetts with his wife, Susan Bell Dennett , and they have two children.

Teaching

The naturalistic view of people

“ Man is a natural being that emerged from the animal world in the process of evolution .” According to Dennett, this is “ Darwin's dangerous idea” (1995), which forces us to take a naturalistic view of man. This means, according to Dennett, that there is nothing fundamentally puzzling about the essence of human beings, nothing that the natural sciences cannot - in principle - explain. According to Dennett, this general position has the consequence that the theory of evolution also plays a central role in explaining human behavior and thinking. However, since cultural evolution cannot be explained by gene selection , Dennett has become a well-known proponent of the meme concept . For Dennett, memes are the analogues of genes in cultural evolution.

Dennett describes himself as an atheist , but he is just as certain about his rejection of God as he is about other unverifiable statements (such as Russell's teapot ). Dennett belongs to the Brights , who see themselves as a group of people with a naturalistic worldview. When the concept of the Brights emerged in 2003, Dennett also penned an article, The Bright Stuff, in the New York Times . He started the article with the following words:

- “The time has come for us Brights to confess. What is a bright? A bright is a person with a naturalistic worldview, devoid of the supernatural. We Brights don't believe in ghosts, elves or the Easter Bunny - or in God. "

An empirical explanation of consciousness

Dennett was deeply impressed by Descartes ' philosophy during his studies . But now he tries to show why Descartes' assumptions about consciousness are wrong. Dennett rejects Cartesian dualism and advocates functionalism . His approach to an explanation of consciousness is:

"The conscious human mind is something like a sequential virtual machine that is - inefficiently - implemented on the parallel hardware that evolution has given us."

With the term Cartesian theater coined by him, he also encounters the idea that there is a central point in the brain where neural processes are converted into consciousness. According to Dennett, consciousness is less like television and more like fame, although a less ambiguous term is the English slang expression clout , which has no exact equivalent in German.

Qualia eliminativism

Dennett argues that in the future, consciousness could be fully explained by the neurosciences and cognitive sciences . A classic problem is the experience content (the qualia ) of mental states. If you prick your hand with a needle, it not only leads to certain activities in the brain and ultimately to certain behavior - it also hurts (it has a “quale”, the singular to qualia). The fact that it hurts and that the activities in the brain do not proceed without a sensation of pain lead Dennett to the conclusion that every experience of consciousness is linked to a neurological process. Dennett is referring here to formulations of the qualia problem such as those put forward by Thomas Nagel , Joseph Levine, and David Chalmers .

Most naturalistically minded philosophers try to show why experience arises from certain brain processes, functional states or the like. Dennett, on the other hand, is of the opinion that the quality problem is a bogus problem . By analyzing an empirical experiment in relation to change blindness , Dennett shows that claims about qualia are either accessible from “heterophenomenology” or inaccessible from a first-person perspective .

Intentionality

But the experience content is not the only phenomenon that makes consciousness appear puzzling: people are not only experiencing, but also thinking beings. Philosophers discuss this fact under the term “ intentionality ”, which is characterized by its directionality: The thought p is directed to the state of affairs P. This also makes it true or false: the thought that Herodotus was a historian is obviously true, and that's because the thought is directed to a real issue.

But this begs the question of how humans can have intentional states, for brain activity cannot be true or false, any more than electrical impulses in the brain can be directed towards Herodotus and the fact that he was a historian. Most naturalistically minded philosophers now try to show that this is possible in some way.

Dennett, however, points out that we can describe systems in different ways. First of all, there is a physical attitude: you can describe a system in terms of its physical properties and thus predict its behavior. However , it is often not possible to predict the behavior of a system in a physical setting due to reasons of complexity. At this point one can resort to a functional setting : To understand a clock and predict its behavior, one only needs to know the construction plan; the concrete physical realization can be neglected. But sometimes systems are even too complex to be dealt with in a functional setting. This applies, for example, to us humans or to animals. This is where the intentional attitude comes into play : the behavior of a system is explained by giving it thoughts. This is how one predicts the behavior of chess computers: "He thinks that I want to sacrifice the rook."

Dennett's answer to the problem of intentionality is: A being has intentional states when its behavior can be predicted with an intentional attitude. In this sense, humans are intentional systems - but chess computers also have this status. Dennett's position is also called instrumentalism , in which the concept of "intentionality" is a useful fiction . Dennett has partially revised this position in his more recent work. He calls himself a “weak realist” and thinks that intentional states are as real as patterns, for example. Think of a carpet: the pattern on it is not real in the same sense as the carpet itself. Still, the pattern is not just useful fiction.

Freedom and self

The naturalistic program is often viewed with discomfort because it seems to attack the classical conceptions of freedom and self- image. Even if Dennett is generally not afraid to draw far-reaching conclusions from the naturalistic program, he does defend the concepts of freedom and self to a certain extent.

In order to answer the question of whether people are free, it must first be clarified what is meant by the term “freedom”. If freedom is understood to mean (partial) independence from the laws of nature , according to Dennett we are not free. If, however, freedom is understood to mean wanting and acting to the best of one's knowledge and belief, one can actually claim freedom. Dennett favors the second reading.

Dennett sees a similar situation with regard to the self. If “self” is understood to mean an immaterial substance (such as the soul ) or a general functional center in the brain, according to Dennett there is no self. Nevertheless, according to Dennett, people all have a self in a different sense: leitmotifs, repetitions, prominent features formed in people's life stories. In this way a self is constituted, which Dennett also calls the “center of narrative gravity” (or narrative focus; center of narrative gravity ). It can only be because the person speaks a language of words or gestures .

Awards

- 2001 Jean Nicod Prize

- 2004 Humanist of the Year Award

- 2007 Richard Dawkins Award

- 2012 Erasmus Prize

documentary

Dennett also appears in the documentaries The Atheism Tapes (2004) directed by Jonathan Miller . The Atheism Tapes contains interviews with six important personalities from the fields of philosophy and science. Dennett speaks about religion and atheism in a half-hour interview.

Fonts

- Content and Consciousness. Routledge & Kegan Paul, Humanities Press, London / New York 1969.

- Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology. Bradford Books and Hassocks, Montgomery, VT 1978.

- with Douglas R. Hofstadter : The Mind's I: Fantasies and Reflections on Self and Soul. Basic Books, New York 1981.

- German: Insight into the self. Fantasies and reflections on self and soul. Klett-Cotta, 5th edition Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-608-93038-8 .

-

Elbow Room: The Varieties of Free Will Worth Wanting. Bradford Books / MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. 1984.

- German: elbow room. The desirable forms of free will. Beltz Athenaeum, 2nd edition 1994.

- The intentional stance. Bradford Books / MIT Press Cambridge, MA. 1987.

-

Consciousness Explained. Little, Brown, Boston 1991.

- German: philosophy of human consciousness. Translated by Franz M. Wuketits , Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-455-08446-X .

-

Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life. Simon & Schuster, New York 1995.

- German: Darwin's dangerous legacy. The evolution and the meaning of life. Hoffmann & Campe, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-455-08545-8 .

-

Kinds of Minds. Basic Books, New York 1996.

- German: Varieties of mind: how do we know the world? A new understanding of consciousness. Goldmann, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-442-15111-2 .

- Brainchildren - Essays on Designing Minds. MIT Press, Bradford Book, 1998.

- Freedom Evolves. Allen Lane Publishers, 2003.

-

Sweet Dreams. Philosophical Obstacles To A Science Of Consciousness. MIT Press, Bradford Book, 2005.

- German: Sweet dreams: The exploration of consciousness and the sleep of philosophy. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 2007, ISBN 978-3-518-58476-7 ; Review by Michael Pauen .

-

Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. Viking Books, 2006.

- German: Breaking the spell: Religion as a natural phenomenon. Insel, Frankfurt 2008, ISBN 978-3-458-71011-0 .

- Science and Religion. Are they Compatible? (with Alvin Plantinga ). Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-973842-7 .

- From bacteria to Bach - and back: the evolution of the spirit . From the American by Jan-Erik Strasser. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2018. ISBN 978-3-518-58716-4 .

literature

- Bo Dahlbom (Ed.): Dennett and His Critics: Demystifying Mind. Philosophers and Their Critics. Blackwell, Oxford 1993.

- Don Ross, Andrew Brook, and David Thompson (Eds.): Dennett's Philosophy: A Comprehensive Assessment. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. 2000.

- John Symons: On Dennett. Wadsworth Philosophers Series. Wadsworth, Belmont, California 2002, ISBN 0-534-57632-X .

- Andrew Brook, Don Ross (Eds.): Daniel Dennett. Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Matthew Elton: Daniel Dennett. Polity Press, 2003.

- Christian Tewes: Fundamentals of consciousness research: studies on Daniel Dennett and Edmund Husserl. Alber, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-495-48235-3 .

- Tadeusz Zawidzki: Dennett. Oneworld, Oxford, 2007, ISBN 978-1-85168-484-7 .

- David L. Thompson: Daniel Dennett. Contemporary Amerciavn Thinkers. Continuum, New York, 2009, ISBN 978-1-8470-6007-5 .

- Bryce Huebner (Ed.): The Philosophy of Daniel Dennett. Oxford University Press, 2018, ISBN 978-0-19-936751-1 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Daniel Dennett in the catalog of the German National Library

- Dennett's homepage

- Daniel Dennett in an interview with “Sternstunde Philosophie” on February 18, 2018

References

- ↑ biography

- ^ Daniel C. Dennett: The Bright Stuff. In: The New York Times . July 12, 2003, accessed on November 18, 2015 (English): “The time has come for us brights to come out of the closet. What is a bright? A bright is a person with a naturalist as opposed to a supernaturalist world view. We brights don't believe in ghosts or elves or the Easter Bunny - or God. "

- ↑ (translated from: Daniel Dennett: Consciousness Explained. Back Bay Books, New York, Boston, London 1991, p. 218.)

- ↑ Daniel C. Dennett: Sweet Dreams - The Exploration of Consciousness and the Sleep of Philosophy. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 2007, p. 155.

- ↑ Daniel C. Dennett: Sweet Dreams - The Exploration of Consciousness and the Sleep of Philosophy. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 2007, p. 156.

- ↑ Daniel C. Dennett: Sweet Dreams - The Exploration of Consciousness and the Sleep of Philosophy. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt / Main 2007.

- ^ Daniel C. Dennett: Brain Development: No Consciousness Without Language. In: Spiegel Online . September 18, 2008, accessed November 18, 2015 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Dennett, Daniel |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Dennett, Daniel Clement |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 28, 1942 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Boston |