Deocar

Deocar († before 826; Latin Deo carus "Gottlieb") was abbot of Herrieden Abbey and is venerated today as a saint and in Herrieden as the founder and patron of the city.

Origin and advancement as a clergyman

Saint Deocar stands at the beginning of church life in Herrieden; Herrieder's local history is documented in it for the first time. It can no longer be proven with certainty where it came from.

In the middle of the 8th century Deocar and Rabanus Maurus were a student of the learned Alcuin von Tours in the Fulda monastery . He later became a monk and priest there. Studies at the Carolingian court academy followed in Fulda years of teaching. Probably after 771 he worked as court chaplain in the chancellery of Charlemagne .

Abbot of the Herrieden monastery and royal messenger

In a dispute with the Bavarian Duke Tassilo III. The Franconian ruler raised claims to the Hasareoda monastery founded by Cadolt on the Altmühl (later Herrieden) and appointed Deocar abbot there in 782/83. In addition to managing his monastery family, the young abbot soon developed an extensive preaching of faith among the population. After the subjugation of the Avars in 791/95, the Herrieden Abbey is the only Franconian monastery to participate in the missionary work in the new East Mark, the king transferred the villages of Melk, Pielach and Grünz to Deocar.

Crowned emperor at Christmas 800, Charlemagne commissioned Deocar with the important office of a royal messenger . In Regensburg in 802 and in the Diocese of Passau around 804 he is documented in this capacity. A letter to Deocar has come down to us from the correspondence of the most influential court theologian, Alcuin von Tours .

Together with the Archbishop of Mainz Haistulph and the most outstanding monks of the convent, Deocar transferred the relics of St. Boniface to the new honorary grave of the west crypt on November 1, 819 at the consecration of the mighty basilica in Fulda .

Death and veneration as a saint

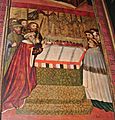

Archbishop Arn of Salzburg - Deocar connected in many ways - inscribed the friend in the fraternization book of Stift Sankt Peter (Salzburg) , among the living bishops and abbots, before 821 . In 826, the Reichenau monastery no longer mentions Deocar, but only his monastery; therefore he could have died in the meantime. Recent research also names 829 as the year of death. He was buried in the old monastery church in Herrieden . There Deocar's memory survives the conversion of the abbey into a canon monastery, in whose new collegiate church Deocar also found a second burial place. First evidence of cultic veneration date from the time of Bishop Gundekar II of Eichstätt (1057-1075). In the Pontifical Gundekarianum he is shown in one of the miniature paintings.

In the fight for the imperial title, the later Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian was able to conquer Herrieden in 1316 with the help of the city of Nuremberg and therefore gave the Nuremberg residents some of the Deocar relics, including the head, that were resting there. These came to be worshiped in the Nuremberg Lorenz Church , where the saint was donated a silver reliquary and an altar, which was made in 1437. St. Deocar advanced to become one of Nuremberg's patrons and an important pilgrimage developed, the proceeds of which largely financed the construction of the large late Gothic hall choir of St. Lorenz. On the day after Pentecost, the city always held a large Deocarus procession, during which the youngest councilors carried the silver shrine. With the Reformation, interest in the veneration of the saint died out, but the altar and reliquary were preserved. In 1811 the silver shrine had to be delivered to the Kingdom of Bavaria for its material value and was melted down. The Nuremberg relics originally stored there were transferred in 1845 at the request of Eichstatt Bishop Karl August von Reisach to his cathedral , where they are still located today.

Ludwig the Bavarian kept a smaller part of the relics for himself in 1316 and brought them to the Munich Residence , where they were destroyed by bombs in the Second World War .

Another part of the relics remained in Herrieden in 1316. In 1472, Bishop Wilhelm von Reichenau had a gothic high grave built for this purpose and it was stored in it. For the 1000th anniversary of the abbey in 1783, the bones were placed in a glass shrine on the high altar of the collegiate church. In the wake of the secularization of the monastery (1804), Deocar's historical figure faded almost into legend; the anniversary year 1982/83, for the 1200th anniversary of the foundation of the Herrieden monastery, aroused new interest in the veneration and history of St. Deocar; The pilgrimage day of the local saint is June 7th.

Representations

literature

- Veit Gottlieb Baumgärtner: Brief biography of St. Gottlieb (Deocar), first abbot and patron saint of Herrieden , Herrieden monastery, 1783.

- City of Herrieden: Herrieden - City an der Altmühl , Herrieden city administration, 1982

- Corine Schleif: Image and written sources on the veneration of Saint Deocarus in Nuremberg , special print in the 119th report of the Bamberg Historical Society, 1983

- Association for the preservation of St. Lorenz Church Nuremberg: Stephanus, Laurentius, Deocar - church patrons and altar saints , Nuremberg, 2001, issue 46 of the association's documents

- Martin Baier: The adoration of the Holy Abbot Deocar in Herrieden and at the Lorenz Church in Nuremberg , Herrieden, 2005, (printed study paper)

- Ekkart Sauser : Deochar (Dietger). In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 21, Bautz, Nordhausen 2003, ISBN 3-88309-110-3 , Sp. 330–331.

Web links

- Website of the parish of Herrieden about the history and veneration of St. Deocar

- St. Deocar in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints portal

- Figure Deocars in the Pontifical Gundekarianum

Individual evidence

- ^ Association for the Preservation of St. Lorenz Church Nuremberg: Stephanus, Laurentius, Deocar - Church Patrons and Altar Saints , Nuremberg, 2001, Issue 46 of the Association's publications, page 34

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Deocar |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Abbot of Herrieden |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 8th century |

| DATE OF DEATH | before 826 |