German economic history in the First World War

The First World War also differed from earlier European wars in that it was the first war that took place between largely industrialized countries. The economic potential of the participating states therefore also became decisive factors for the outcome of the war ( material battle ).

German war economic policy had four basic goals:

- the production of sufficient war material (ammunition, weapons, other equipment) for the new form of war of material battles, for this purpose above all securing the supply of raw materials,

- the division of labor or soldiers between the army and the economy, especially armaments factories, in order to keep both functional,

- maintaining social peace by balancing the interests of employers, workers and the belligerent state,

- the security of food supplies despite the economic blockade imposed by the Allies .

The various government interventions did not solve any of these problems. At the end of the war, the individual problems combined to form a comprehensive crisis in which social issues were of paramount importance.

Then there were the challenges of financial policy: in 1918 the Reich's war expenditures amounted to 50 billion marks. That was more than eleven times the imperial spending in the last year of peace. Since, for various reasons, including the maintenance of social peace, the financing of the war was not to be carried out through taxes but through borrowing , massive interventions in the financial sector took place from the start. In addition, this approach had all of the negative consequences known from a debt- based economy .

War economic plans before the start of the war

The economic measures had initially been taken on the assumption that the war would be over in a few months - according to the experiences from the wars of 1866 and 1870/71 . Internationally, too, politics and business assumed that a modern state would not be able to wage war over a long period of time. It was suggested that the associated economic constraints would quickly force one side to give up. In addition, as a result of this economic downturn, unemployment was expected to rise , which should ensure the supply of soldiers for the army. Another wrong assumption was the expectation of extensive raw material loot from the conquered areas.

Accordingly, when the war broke out there were no authorities dealing with the war economy . In the German Reich, the civil economic administration was also divided between the Reich authorities and the authorities of the individual states. Due to the state of siege , which was declared in August 1914, the military began to interfere increasingly in the economic administration. This task lay primarily with the deputy commanding generals of the army corps. They were the commanders of those parts of a corps that remained in their home region. These deputy commanding generals were given almost dictatorial powers with the state of siege . Their jurisdiction was broad and was expanded more and more by declaring new areas of economic and social administration as "important to the war effort" and attracting them. Parallel to this, and in some cases overlapping, there were various other authorities with similar tasks, the most important of which was the military-led Prussian War Ministry , which was responsible throughout the Reich for the procurement of equipment and personnel for the field army. But there were exceptions to this, too: responsibility for pioneering material initially fell under the sovereignty of the Bavarian military administration. These unclear delimitations, together with the lack of economic expertise in the military and the inconsistent civil and corps boundaries, quickly led to increasing administrative chaos.

War economy 1914 to 1916

Military goods

However, shortly after the start of the war, efforts to reform the economic administration began. The reason was the looming munitions crisis . At the beginning of the war, the army had given the German arms industry sufficient supplies. As early as August 1914, AEG board members Walther Rathenau and Wichard von Moellendorff made the new chief of staff Erich von Falkenhayn aware that the British naval blockade was unexpectedly effective and that the nitrogen supply for the production of explosives was in danger of collapsing. At this point in time, according to the estimates of the industrialists, stocks were only sufficient for half a year. In view of this situation, the War Ministry founded the War Resource Department (KRA) on August 13th . Experts from the business world worked there, which was the first time the War Ministry hired civilians on a large scale. Since it was founded, the KRA has met with strong rejection from parts of the private sector because it intervened massively in economic activity. She saw her main task in supplying the private sector with the raw materials it needed. In addition, these were managed centrally, which also included confiscation and redistribution.

The ammunition crisis initially worsened: at the beginning of November, ammunition was only available for six days. After that, economic management began to take effect and the supply situation in the German military slowly relaxed. In order to end the total dependence on the now interrupted imports of saltpetre from Chile , Falkenhayn started direct negotiations with the industry. This resulted in massive research efforts to make the Haber-Bosch process for extracting saltpetre from atmospheric nitrogen ready for industrial mass production. In addition, the German chemical companies were merged to form a syndicate , the War Chemicals Society. Nevertheless, according to the military, the supply of ammunition remained inadequate. The industry hardly succeeded in adapting to the constantly changing demand for different types of ammunition at the front. The companies increased their production capacities only slowly because they expected little profit in view of the expected short duration of the war. Only later did the armaments industry use the war to impose high prices on the Reich for its products.

The KRA quickly founds a number of individual companies for various raw materials. They were private joint-stock companies under strict government supervision. This connection of private economic elements with state organization was called " state socialism " by contemporaries . The raw material companies met with massive resistance in the economy because the company representatives represented on their supervisory board prefer their own companies in the distribution. At the beginning of the war, the coercive means of allocating raw materials was used only in a few cases, but later on to a larger extent. In the autumn of 1914, the KRA also began to intervene in the pricing of the industry. Overall, it was possible to avert the impending collapse of raw materials.

Chaotic structures continued to rule in the procurement departments of the War Ministry. Corruption was also widespread in the more than 40 procurement offices. From the beginning of 1915, the War Ministry countered this with strict controls: Companies that applied for army contracts had to allow insight into their calculations . The ministry was able to just calculate the new contracts concluded as a result, as it was now informed about the processes and cost structures of production. This step was intended to limit expenditure and also prevent inflation (the latter did not succeed, see German inflation 1914 to 1923 ).

The disclosure requirement led to renewed protests from the business community.

Manpower

Before the war, there had been no plans for the distribution of labor between civil and military production or for recruiting for the army. Initially, the most skilled workers were called up, which in turn led to a flood of requests from industry for deferral. However, this request was not provided for in the military administration and there was no orderly bureaucratic procedure for it. The industry then threatened to refuse military orders.

In January 1915, the "Department for Restitution" AZ (S) was created, which was dominated by social reform scientists and bureaucrats. In May 1915, the War Ministry was increasingly involved in the until then largely autonomous drafting process in the army corps districts. The AZ (S) and other departments of the ministry could only make recommendations. The decision on convocation rests with the deputy commanding generals. In addition, the agencies tried to expand the employment of prisoners of war and injured persons as well as foreign workers. In the spring of 1915, workers were classified according to their physical condition, and industry had to hand over the fittest to the army. In June 1915, the first binding directives for deferrals were issued to the deputy general commands. On the other hand, the ministry enforced the release of the most fit workers for military service by awarding army contracts to companies that did not oppose it. From the beginning of 1916 the AZ (S) carried out more initiatives to employ women, young people and prisoners of war.

A hallmark of the war economy was that women took the place of drafted men in agriculture, trade and commerce. However, research today assumes that the increase in women's labor was not significantly higher than before the war. In many cases, it was a question of shifting existing female employment, for example from domestic work to industry. Women who had previously not been employed were less likely to take up industrial employment, but were more likely to work in service occupations. Working from home also played a major role . Despite all the relativization of the quantitative importance, the public - often with a critical undertone - noticed above all the growing number of women in industry even in heavy industry. Even contemporaries saw the assumption of male professions as an emancipatory progress. But research has long been skeptical that this was a permanent process. After the war, the returning men took up the jobs that women had occupied during the war. The traditional gender ratio has also been restored.

Since 1915 the use of prisoners of war in the economy increased. In 1916 90% of the approximately 1.6 million prisoners of war in Germany were employed in industry (330,000) but above all in agriculture (750,000). These numbers grew as the war continued. Only a small proportion of the prisoners lived in the prisoner of war camps. The vast majority of around 80% were assigned to different work units. The use of prisoners of war was prohibited by the Hague Land Warfare Regulations in armaments factories, but this prohibition was evaded the longer the war lasted.

Foreign civil workers also played a role. Immediately after the start of the war, the numerous seasonal workers from the Russian part of Poland were prevented from returning to their homeland. In the winter of 1916/17 in particular, forced labor measures were carried out in the occupied territories of the General Government of Warsaw , in Upper East and in the General Government of Belgium , but were soon abandoned with the exception of Upper East. Instead, one again relied on the recruitment of workers.

food

The food supply was also initially completely ignored by the government.

The self-sufficiency rate was significantly higher in Germany than in Great Britain. Nevertheless, Germany was heavily dependent on imports. In addition to the actual food, feed grain and raw materials for artificial fertilizers such as chile saltpeter or raw phosphate had to be imported. In the 1912/13 marketing year, for example, almost 4.2 million tons of feed grain were imported. There are different figures for the amount of food imports. The estimates range between 10% and 20%. Only when general bottlenecks in the German war economy occurred in 1916 did the British naval blockade become a "hunger blockade". Nevertheless, the shortage of imported goods at the beginning of the war was considerable. The central purchasing company was founded to procure food in particular from neutral countries . The blockade also ensured that necessary raw materials such as nitrate for the production of artificial fertilizers no longer came into the country. The first price increases towards the end of 1914 led to unrest. Social democrats, bureaucrats and business were calling for food policies, and local authorities began setting maximum prices, which was not very effective.

On November 17, 1914, the War Grain Society was founded against the opposition of the representatives of agricultural interests in the Reich Office of the Interior . Following the example of the KRA, it should buy up supplies, set high prices and thereby achieve lower consumption and a longer range of supplies. This concept only partially worked. In February 1915 a series of regulations on grain production followed, in which the government was given control of all farmers' stocks. In January 1915 there was the first bread rationing in Berlin, in June in the whole Reich. Control of other foods was tried, but hardly succeeded. The farmers reacted by trading in the black market and switching to other products. In October 1915, the Reichskartoffel -stelle was founded. The instruction in 1915 to reduce the number of pigs by 5 million by slaughter due to lack of feed (popularly known as pig murder), led to an undersupply of meat.

Overall, the food administration failed because of the cumbersome bureaucracy, the different approaches in different authorities and the conflict between the agricultural-related administrations of the federal states and the consumer-oriented attitude of the deputy commanding generals. These problems led to increasing demands for military control of food distribution, especially from the ranks of the SPD. In 1916, a poor potato harvest led to hunger riots and increasing tensions between urban and rural populations. Industrial production also began to suffer from the poor diet of the workers.

The War Food Office (KEA) was founded in May 1916 . It was limited by the fact that it had no influence on the army supply and had no executive options of its own, but was dependent on the imperial offices. Nevertheless, it was the first central feeding station. At the same time, the powers of the Deputy General Command for the civilian food supply were severely curtailed. This did not solve the problems, but the supply of industrial workers improved slightly. The basic problem of insufficient food production remained.

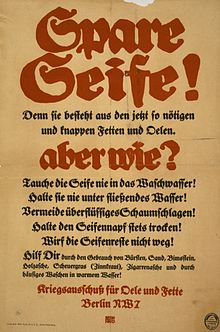

Since 1915, the production of substitute food increased sharply. Their quality and nutritional value were often poor. A uniform authorization requirement was only introduced towards the end of the war.

Social policy

Social policy was also subject to the requirement to maintain economic production. The state tried to avert the danger of strikes or even a revolution. From 1915 the War Ministry pursued a resolute social policy. The AZ (S) quickly became the bearer of a progressive, union-friendly social policy, but the repressive approach of compulsory labor was also discussed internally. The AZ (S) and other government agencies intended to motivate workers to go to war by granting them rights in their functions. This attitude came the burgfriedenspolitik the SPD opposed the war and friendly course of trade unionists.

The involvement of workers was intended to solve various economic problems. After the drafts at the beginning of the war, there were massive attempts to poach the remaining workers. Companies with war contracts recruited skilled workers from other companies. In February 1915 a first corporatist solution was attempted with the establishment of the " Metal Committee for Greater Berlin ". In it, employers and employees negotiated jointly about the justification of requests for a change of job. Mostly compromise solutions were found along the lines of “more wages and staying at the old job”. In the rest of the empire, similar institutions were slow to come about. It was not until January 1916 that the next war committee was founded in Dresden . In April 1916, the Reich Office of the Interior finally prescribed the establishment of committees or arbitration boards made up of employers, employees and officers. However, industry was able to prevent this in individual regions, especially in the Ruhr area and Silesia , where deputy commanding generals were close to it. In addition, army contracts often prescribed reasonable wages for workers. The AZ (S) eventually even began to discuss vacation-granting plans. Its close union stance earned the authority repeated sharp criticism from the business community and the Prussian Ministry of Commerce.

War economy 1916 to 1917

In the early summer of 1916, the massive rise in war costs led to a military, political and economic crisis: more than a tenth of the annual national income of 1913 was consumed in one month at that time. From the fifth war bond (September / October 1916) onwards, the subscription results could no longer keep pace with the need for money ( for the coverage ratio through the war bonds, see the table in the article German inflation 1914 to 1923 ).

Hindenburg program

In August 1916 Paul von Hindenburg became Chief of Staff and Erich Ludendorff became Chief of Staff and Quartermaster General . Together they led the third Supreme Army Command (OHL), which largely disempowered the War Ministry. The extensive use of all economic resources required by them for the war and the strong expansion of arms production was soon referred to as the Hindenburg program . It was based on the British Munitions of War Act 1915 , on the basis of which the British war economy had proven its efficiency in the Battle of the Somme in July 1916. The offensive on the Somme had led to another serious munitions crisis on the German side. There was also a catastrophic food shortage. Immediately after taking office, the new OHL demanded a massive increase in ammunition and weapons production, also at the instigation of the lobbyists of big industry, in order to compensate for the shortage of soldiers. Economic, financial and manpower considerations were initially radically subordinated to the demand for more ammunition. The OHL presented the program as a departure from the inadequate policy of the War Ministry. The Hindenburg program was only fulfilled in a few partial aspects. His high standards and focus on arms production even made the crisis worse. It also made larger provisions from the front necessary.

War Office

In November 1916, the War Office was founded under Lieutenant General Wilhelm Groener , which took over numerous economic tasks for the War Ministry, was more closely linked to the OHL and was organized militarily. At the same time, the autonomy of the deputy commanding generals was restricted. With the office new bureaucratic problems arose, since it was subordinate to both the deputy general commands and the ministry and the war ministries of the states kept their duties. Both the SPD and industrialists welcomed the new agency as they expected it to be more effective in administration. Overall, these expectations were not fulfilled, despite the occasional sensible administrative measures, particularly with regard to food supply. The confused internal organization of staffs and departments, overlaps with civil and other military authorities led to bureaucratic inefficiency.

Auxiliary Service Act

The discussion about compulsory work, which had already been held repeatedly, was given a boost with the 3rd OHL. Above all, the industry made itself strong. In October 1916 there were first compulsory obligations for Belgian workers. In November 1916, the War Office's first draft for the Auxiliary Service Act (HDG), actually the law on patriotic auxiliary service , was presented. It was intended to oblige the entire male population, especially for agriculture and the war industry, to restrict the free movement of workers and to allow companies to shut down or merge in order to achieve more efficient production. There had already been massive political discussions and lobbying work by employers' associations and unions on compulsory labor. The implementing provisions of the HDG provided, among other things, for a committee system that was to decide on the importance of companies in the war and thus on the allocation of workers and ultimately the existence and regulate the change of job for workers. In the Reichstag debate on the HDG in November 1916, representatives of trade unions and companies clashed. As a result, a Reichstag committee was established to control the HDG, and permanent workers' committees with the right to represent in collective bargaining issues were formed in larger companies. This can be seen as the cornerstone for employee participation in Germany. Together with the participation in the HDG committees, this meant a huge gain in power for the unions. In addition, the limitation of war profits for companies was discussed without result. When the law was passed, the government made an oral undertaking not to use the full force of the law, but rather on a voluntary basis if possible, to enforce both compulsory work and the closure of factories. In December 1916 the law was passed.

The hoped-for effect of the HDG, the reduction of provisions, did not materialize to a large extent; rather, they increased because the industry refused to employ unskilled workers. Very few civilian volunteers were found, mostly women. In the spring of 1917, the situation at the front worsened, whereupon Ludendorff restricted the provisions. In March 1917, the tightening of the mandatory registration for those required to do so was not implemented across the board. The HDG completely failed to capture the middle and upper classes. On the other hand, the War Office began to seek more female workers, taking social aspects ( child care ) and appropriate working conditions into account. The increasing number of women working in industry had negative effects in agriculture. Even the mergers of companies under the HDG did not achieve the desired savings in labor and transport capacity. In December 1916, the Standing Committee for the Merger of Enterprises (SAZ) in the War Office was formed from representatives of the authorities and businesses. First mergers in the textile industry led mainly to the consolidation of large companies, which resulted in public and parliamentary protests. Further mergers mostly failed due to the resistance of the companies, which, with the help of the procurement offices, presented themselves as important to the war effort. In the course of 1917, the power of decommissioning was increasingly taken over by the coal commissioner because the coal supply was becoming increasingly critical. From the summer of 1917, the closures also extended to operations that were important to the war effort, because the shortage of soldiers was increasing. At the same time, over the entire course of the war, with a view to the coming peace economy, "non-war" industries were kept alive and so capacities were wasted. The main problem of the HDG, however, was Paragraph 9. It was supposed to regulate the change of job and allowed the change to "reasonable improvement" of wages and working conditions. Arbitration committees mediated in conflicts between workers and employers. In the spring of 1917, this created total chaos on the labor market: workers, including those who were postponed, used the regulations to get better-paid jobs. Employers recruited workers to a greater extent than before with higher wages. Among other things, this led to a general rise in wages, a large wage gap between workers in the war industry and the rest of the workforce, and accelerated inflation.

Transport and coal crisis

The transport and coal crisis began in the autumn of 1916 and lasted into the spring of 1917. The railway infrastructure had previously received little attention, although the railroad had become the most important means of transport after inland waterway transport had also declined due to the blockade of the seaports. Additional requirements for the transport of troops, weapons and ammunition tightened the requirements for the railroad after Romania's entry into the war in August 1916. The collapse came with the Hindenburg program. The infrastructural nonsensical new construction of industrial plants (steel production in the Ruhr area, processing around Berlin, transport to the front) also required high track construction capacities. There was an increasing shortage of workers to unload the wagons. In September 1916 there were the first serious disruptions in coal transport in the Ruhr area, which in October resulted in production losses in armaments factories, which quickly spread to the entire Reich. The coal transport largely collapsed. Loaded trains got stuck or could not be unloaded. From October 1916 an attempt was made to organize the transport system centrally, but this had hardly any effect and instead led to more bureaucratic confusion. The military control of the railroad system called for in the press did not take place, but the deputy commanders used their troops to unload the trains. In addition, the OHL tried to force the construction of rails and trains. When inland shipping came to a standstill due to the severe frost in January and February 1917, the crisis worsened and transport bans for several days were imposed to unravel the chaos. This further damaged production, but relieved the railway.

As the transport crisis subsided, it became increasingly clear that there are also considerable problems in coal production because many miners had been called up. Since a high level of production was to be maintained in spite of this, and above all because of the Hindenburg program, the pits were in a poor condition, which in the meantime also had an impact on production. Even the coal commissioner, who was put into service in February 1917, could not improve the supply, but rather increased the bureaucratic chaos. Ultimately, the rail and coal crisis led to the failure of the Hindenburg program. Arms and ammunition production collapsed in January and February 1917, which was one of the reasons for the withdrawal on the Western Front to the "Siegfried Line".

"Turnip winter" / "Turnip winter"

The winter of 1916/17 is known as the turnip winter because of the food crisis . In view of the catastrophic situation, the food rations were cut again significantly. The war food office failed completely. Only tough measures by the War Office improved the situation: the farmers were given more workers, horses and fertilizers. In January 1917, war economic offices were established in the provinces. On the one hand, they established the farmers' requirements for maintaining production and regulated their supply, in some cases with work by garrison troops. For this purpose, the population was also supplied with soup kitchens in which dishes made from turnips , a food that was still available, were offered. On the other hand, the authorities confiscated hoarded and hidden food. However, they were also unable to achieve the intended standardization of food rations.

inflation

In 1917 the difficulties of financing the war began to have an increased effect. Attempts to cover war costs with new taxes did not begin until 1916 and had little success. The state borrowed through war bonds domestically. But they only brought part of the necessary capital. Therefore, the Reichsbank began to print money, causing inflation that was exacerbated by rising wages in the war industry. From the summer of 1917 one can speak of galloping inflation.

Strikes

In addition, economic policy was less and less able to meet its social demands. The USPD intensified its agitation from the beginning of 1917. After the bread rations were cut, local hunger protests in Berlin and Dresden turned into massive strikes in April. In Berlin, the unions quickly brought some of the factories to rest. In Leipzig the strikes took a political direction; Suffrage reforms, peace negotiations and an end to domestic repression were called for. The military finally cracked down on them, occupying some factories and sending conscripts on strike to the front. A new wave of strikes began in June 1917 in the Ruhr area with food riots. Soon there were political demands there too in view of the Russian February Revolution . Next, the strikes spread to the Silesian coal fields. In view of these crises and after intrigues by the OHL, Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg resigned on July 13th . The strikes ended at the beginning of August following military repression.

In cooperation with the War Office, KEA and Coal Commissioner, a new coal and transport crisis was largely averted in the winter of 1917/18.

Economy in the last months of the war

In the worsening crisis that began in the summer of 1917 and encompassed all areas of the military, politics, society and economy, hardly any economic policy measures were taken. Various programs and new regulations were considered, but hardly anything was implemented in the increasing chaos. Solving immediate emergencies took the place of far-reaching concepts. There were inconsistent, sometimes contradicting actions by the OHL. Avoiding a revolution became the central goal of domestic politics.

After the dismissal of War Office chief Groener in August 1917, the deputy general commandos were given more powers again, and the state of siege was applied more strictly. On the other hand, the OHL began to recognize the importance of the unions in keeping workers calm. In the second half of 1917 the food supply collapsed completely. The surreptitious trafficking assumed enormous proportions and bypassed state controls. After the entrepreneurs, the municipalities increasingly participated in these forms of trade in order to feed their own population. The lack of food noticeably reduced work performance, which again led to increased demand for provisions. In addition, there were increased calls for political reforms, which culminated in huge strikes at the end of January 1918. The military cracked down and broke the strikes by the end of February. From March 1918 onwards there was calm inside. The supply of the population deteriorated further, for the first time there was also a lack of clothing and living space. Even the rural population began to suffer from a lack of food. The OHL and the government reacted again by setting up administrative and allocation authorities that either over-bureaucratically or insufficiently managed the demand. In April 1918 the bread rations were reduced again. At the same time, the KEA took vigorous action against the illicit food trade by companies.

In the spring of 1918, several legislative processes began in the Reichstag, which laid down the war-related rights of workers for peacetime and were intended to secure their loyalty for the last time. But they didn't come to a conclusion. There have also been isolated attempts by civil and military authorities to restrict both profits and wages. Despite the bad situation, there were no new strikes, as the workers also assumed an imminent military decision.

At the expense of provisions, parts of the Hindenburg program had been fulfilled at the end of 1917, which, however, partially bypassed the need. From 1918 there was also a massive shortage of steel for the first time. Some of the facilities were ineffective because there weren't enough workers. Some of the industry began with the conversion to peacetime production, which led to the construction of numerous new factories and the withdrawal of capacity from war production. In June 1918, the OHL called for compulsory military service to be extended to the age range between 15 and 60 years. A stricter compulsion to work with a firm connection to the workplace was discussed. The British offensive on August 8th finally ended the economic policy of the German Reich.

Social consequences

While the workers and the unions were upgraded because of the shortage of labor, the smaller white-collar workers in particular experienced a marked decline in their incomes. From 1914 to 1916 their salary fell by 20 to 25 percent; because of the parallel inflation, the actual loss of purchasing power was even greater. It is true that in the last years of the war income rose above the pre-war level without compensating for the rise in prices, while workers recorded even greater increases. Thus the social leveling of the group of smaller white-collar workers and the working class increased, which was expressed, among other things, in the establishment of three union-like employee umbrella organizations.

The shortage of men led to the increased recruitment of female workers who, often only briefly trained, had to and were able to take over the jobs previously performed by men. As a result, women's emancipation became even more burning as a social question, but at the same time received a big boost, as it became clear that many activities previously reserved for male workers could also be carried out by women (road and railroad drivers and conductors, clerks / office workers, teachers, assembly line workers ).

The officials , especially in higher positions, reported strong income losses. The real income of the higher officials sank to 47 percent by 1918, the middle to 55 percent, the lower to 75 percent of the pre-war level. One reason for this was the state's inflexible reaction to inflation. In addition, the officials who were not allowed to strike had no leverage. In 1917 civil servants' pay was first introduced based on social criteria. The officials reacted by politicizing and organizing. In 1918 the German Association of Officials was formed from smaller associations.

Craftsmen and traders suffered from the fact that their small businesses were mostly classified as "not important to the war effort" and received hardly any raw materials and workers. Therefore they joined together in larger cooperatives and tried to get army contracts together. A minority of the craftsmen moved closer to the left; the majority sought contact with large-scale industry as producers of preliminary and intermediate goods and through their association structure.

See also

literature

- Sarah Hadry, Markus Schmalzl: Munich is starving. World War and the food crisis 1916–1924. An exhibition by the Bavarian Archive School. Published by the General Directorate of the Bavarian State Archives, Munich 2012, OCLC 780103543 .

- Sandro Fehr: The nitrogen question in the German war economy of the First World War and the role of neutral Switzerland . Nordhausen 2009, ISBN 978-3-88309-482-3 .

Web links

- Hans-Peter Ullmann : Organization of War Economies (Germany) , in: 1914-1918-online . International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. By Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014. doi : 10.15463 / ie1418.10123 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Friedrich-Wilhelm Henning: The industrialized Germany 1914 to 1976. 2nd edition. Paderborn 1974, p. 32.

- ^ Friedrich-Wilhelm Henning: The industrialized Germany 1914 to 1976. 2nd edition. Paderborn 1974, pp. 42-43.

- ↑ Ute Daniel: The war of women 1914–1918: For the interior view of the First World War in Germany. In: Gerhard Hirschfeld, Gerd Krumeich, Irina Renz (eds.): 'Nobody here feels more human ...'. Experience and impact of the First World War. Klartext Verlag, Essen 1993, pp. 132-137.

- ↑ Julia Paulus: The "Mobilization of the Home Army". On gender (dis) order in the First World War. In: On the "home front". Westphalia and Lippe in the First World War. Münster 2014, pp. 54–73.

- ↑ Elke Koch: "Everyone does what they can for the fatherland!": Women and men on the Heilbronn home front. In: Gerhard Hirschfeld, Gerd Krumeich, Dieter Langewiesche, Hans-Peter Ullmann (Hrsg.): War experiences. Studies on the social and mental history of the First World War. Klartext Verlag, Essen 1997, p. 36.

- ↑ Jochen Oltmer: Indispensable workers. Prisoners of war in Germany 1914–1918. In the S. (Ed.): Prisoners of War in Europe during the First World War. Paderborn 2006, p. 68 f.

- ^ Ulrich Herbert: Forced labor as a learning process. On the employment of foreign workers in West German industry during the First World War. In: Archives for Social History . 14/1984, pp. 285-304.

- ↑ Jens Thiel: "Human basin Belgium". Recruitment, deportation and forced labor in the First World War. Klartext, Essen 2007.

- ↑ Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor in the First World War? Recruiting of workers from Poland and the Baltic States for the German war economy 1914–1918. In: Dieter Bingen, Peter Oliver Loew, Nikolaus Wolf (Hrsg.): Interest and conflict. On the political economy of German-Polish relations 1900–2007. Wiesbaden 2008, pp. 143-163.

- ↑ Alan Kramer: Martial Law and War Crimes. In: Gerhard Hirschfeld, Gerd Krumeich, Irina Renz (eds.): Encyclopedia First World War. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2003, ISBN 3-506-73913-1 , pp. 281-292, here: p. 285.

- ↑ Anna Roehrkohl: hunger blockade and home front. The communal food supply in Westphalia during the First World War. Stuttgart 1991, p. 18.

- ^ Martin H. Geyer: Hindenburg program. In: Gerhard Hirschfeld et al. (Ed.): Encyclopedia First World War. 2nd Edition. Paderborn 2004, p. 557.