The embroiderer

|

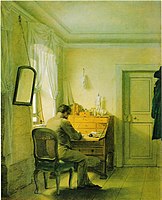

| The embroiderer (1st version) |

|---|

| Georg Friedrich Kersting , 1812 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 47.2 x 37.5 cm |

| Castle Museum, Weimar |

“The embroiderer” (also: “On the embroidery frame” ) is probably the best-known picture by Georg Friedrich Kersting . In addition, it is considered exemplary for the interior painting of the Romantic and Biedermeier period . There are three versions from the years 1812, 1817 and 1827, which differ only slightly.

background

In the summer of 1810, Kersting had enrolled at the art academy in Dresden . In Dresden he joined a group that included Gerhard von Kügelgen , Theodor Körner (writer) , the painter Louise Seidler and Caspar David Friedrich . A very productive phase in Kersting's work began. At the academy exhibition in 1811 he had his first successes with the studio pictures of his painter friends Friedrich and Kügelgen.

Louise Seidler also stayed in Dresden to study painting, but mainly to overcome a great personal loss. In 1806, during the French occupation of Jena , she was engaged to Geoffroy, a French officer and senior physician in the Corps Bernadottes . But Geoffrey died of a fever before the wedding in 1808 during Napoleon's campaign in Spain. Seidler later wrote: “The life of life was closed for me; my existence at that time was just a dull brooding. ”The parents then sent Seidler to Dresden to distract her from her grief and to tear her out of her melancholy. In Dresden, impressed by the paintings in the Dresden art gallery , she began to study painting and became the pupil of Christian Leberecht Vogel .

First version

It was in this context that the embroiderer's first version was created in 1812. The picture shows Louise Seidler at the window, with her face turned away from the viewer , sitting bent over an embroidery frame . The fact that Kersting shows her engaged in such a “typically female” activity, very different from his male painter friends, whom he shows in creative work in the studio pictures, has repeatedly given cause for amazement, since Seidler was recognized as a talent. One possible reason why Kersting shows her as an embroiderer and not as a painter is that the then more or less penniless Seidler, according to her own admission, sometimes embroidered into the night in order to be able to pay for the training hours in pastel painting at Roux with the "needle money" :

- Although I was by far not as skilled at handicrafts as my sister Wilhelmine, who later took care of all her trousseau herself, I tried hard to replace what I lacked. I sewed, knitted and embroidered secretly, often at night, at miserable prices, and in this way earned enough money to pay for tuition at Roux.

On the other hand, it must also be taken into account that embroidery was considered a creative activity at the time. So were Runge , Schinkel and other artists to design not too bad templates for embroidery.

According to Seidler, the room shown is the studio space in Gerhard von Kügelgen's apartment in today's Kügelgenhaus on Dresdner Hauptstrasse . Louise Seidler lived there with her friend Lotte Stieler in the summer of 1812, while Kügelgen and his family had moved to their summer apartment in Loschwitz .

There is a sofa against the back wall, on which are sheet music and a guitar. A portrait of a young man hangs over the sofa with a plant tendril around it, a bindweed . On the windowsill, several flower pots - recognizable hydrangea , myrtle and rose - form something like a barrier. An interpretation based on the language of flowers , which was widespread at the time, is naturally fraught with uncertainties. If one follows a contemporary “floral language” dictionary, the winds would symbolize attachment, the hydrangea (which was newly introduced at the time) coldness of feeling, the myrtle in turn symbolize love and the rose would symbolize chaste inclination, which taken together results in mixed signals. The bindweed and the portrait of the young man are striking, at least insofar as they are replaced in the following versions in contrast to the other pictorial elements.

On the basis of these picture references, the embroiderer was interpreted by Ulrike Krenzlin as a portrayal of a mourning woman: The portrait of the young man is the portrait of the deceased groom, the guitar and notes refer to the making of music in the romantic circle of friends.

Finally, the face that appears in the mirror is also peculiar. From the perspective it doesn't seem to be the face of the seated embroiderer. But it cannot be another person's face either, since the place where they should be is in the viewer's field of vision. This irritation gives the picture something puzzling about which the superficial observer cannot account.

In fact, the impression is based on a sophisticated illusion of perspective, which is created on the one hand by the fact that the mirror is supposed to hang over the chest of drawers on the far right, but actually next to it, and above all by the fact that the window is more or less in the plane of the right wall of the room. In fact, the window is heavily set back.

The counterpart"

On the recommendation of Goethe , who was friends with Louise Seidler, the painting was acquired by Karl August for the ducal Weimar collections in 1812 . According to Seidler, it had previously been shown together with another picture by Kersting, the “Elegant Reader”, at the annual exhibitions of the Ducal Drawing School. Seidler writes in her memoirs:

- Two other pictures that Kersting painted later came to Weimar through Goethe. One, called “the elegant reader”, depicts a young man who reads eagerly by the glow of a studio lamp; the other a young girl working on the embroidery frame in a splendid apartment, whose face can be seen in the mirror opposite. It's my own portrait.

The "Elegant Reader" was later bought after Goethe had organized a lottery for Kersting's benefit. The picture was obtained from Louise Seidler's father, who later sold it to the ducal collection.

The other painting by Kersting acquired at the same time as the first version of “Embroiderer” is therefore not the “Elegant Reader”, but a different picture. In the reports on the exhibitions of the drawing school 1801–1820 the following is listed as an acquisition:

- Mr. George Kersting from Mecklenburg Schwerin. An oil painting depicting a woman sitting and working on the embroidery frame. The counterpart is a gentleman at the desk.

The counterpart mentioned is apparently the painting known today as the “Man at the Secretary”, whereby it is assumed that the portrayed is Kügelgen. The fact that he is a painter is evidenced by the painting utensils on the secretary, the plaster casts and the artist hat on the right of the door.

To appreciate the relative importance of the two images, one has to consider that one of the hallmarks of the Biedermeier style is the propensity for pairing; H. In a room you had two pieces of furniture that were by no means identical, but corresponded in size, style, and manufacturing features, and which were called piece and counterpart. And there was the same thing with paintings. So if the man at the “man at the secretary” is the counterpart of the “embroiderer”, correspondences between the two images will not be accidental.

And such correspondences are numerous: Both pictures show a person sitting at the window and working. The man is shown from behind, the woman has her face turned away. If you place the two pictures side by side, the course of the floorboards suggests a central perspective. A mirror appears on both images in such a way that the two mirrors are symmetrically opposite each other. And in both mirrors a reflection of unclear origin appears: once the face of the embroiderer at the bottom left, and for the “man at the secretary” a white flower at the bottom right.

However, the differences are also remarkable: the embroiderer is shown in an apparently closed room, in which no exit is visible, while the door leading to the outside appears central in the case of the “man at the secretary”, and a coat and hat hanging on the hook next to the door indicate the possibility of going out soon. For this the window is open with the embroiderer, with the “man at the secretary” it is closed and almost “barred” with long-handled pipes.

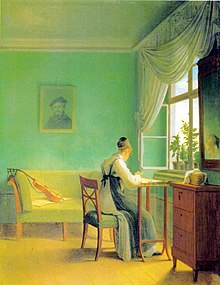

Second version

The second version (47.2 × 36.3 cm) was created in 1817. It was created during Kersting's work as a drawing teacher for the children of Princess Anna Zofia Sapieha in Warsaw , probably in 1817 and is now in the National Museum in Warsaw.

In terms of dimensions and structure, the picture corresponds entirely to the first version. There are several clear differences in the picture elements:

- The embroiderer's dress in the first and third version is high closed, here it leaves the neck free.

- A reflection of the embroiderer's face is not visible.

- The chair and embroidery frame are roughly the same in the first and third versions, here they both differ significantly in shape.

- In place of the portrait of the young man with the tendril, a religious image appears: A Mother of God with a halo and the baby Jesus in her arms, very similar to Raphael's Madonna della seggiola . Among them is a miniature that shows a portrait of a man with a beret in an oval.

- The bricks of the window reveal are visible and suggest a brick wall. The first and second versions show a plastered wall.

Overall, the color mood of the second version is different from the first and third version, which are heavily dominated by light green tones. The shadows are deeper and the colors appear more sedate.

From 1817 onwards, Louise Seidel, supported by a scholarship from Duke Karl August, spent several years studying, first in Munich and then in Italy. During this time she made numerous copies of paintings by Italian masters for the Weimar court, including several Madonnas, to which the Madonna picture on the wall would refer. In particular, her copy of Raphael's “Madonna with the Goldfinch” was declared “the best copy known to him ” by Friedrich Preller , a painter who was also in Italy at the time and with whom Seidler had a long-standing friendship.

Third version

The third version (47.5 × 36.5 cm) was created in 1827. It is now in the Kunsthalle Kiel .

The third version largely corresponds to the first version, with the difference that instead of the picture of the young man, there is a portrait of a bearded man in a beret, possibly the same person who was already depicted on the miniature of the second version. It could be a portrait of Friedrich Preller.

literature

- Georg Friedrich Kersting: Between Romanticism and Biedermeier. Contributions from the V. Greifswald Romantic Conference in Güstrow. Greifswald 1986

- Hannelore Gärtner: Georg Friedrich Kersting. Seemann, Leipzig 1988, ISBN 3-363-00359-5 , pp. 82-87

- Susanne Schroeder: Painting with a needle. In: Kerrin Klinger (ed.): Art and craft in Weimar: from the Princely Freyen drawing school to the Bauhaus. Weimar 2009, ISBN 978-3-412-20244-6 , pp. 39-42

- Sylke Kaufmann (ed.): Goethe's painter. The memories of Louise Seidler . Structure, Berlin 2003

- Hermann Uhde (ed.): Memories of the painter Louise Seidler . 2nd edition, Propylaen, Berlin 1922 digitized . New edition: Kiepenheuer, Weimar 1970 (edited)

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Uhde Memoirs 1922, p. 40

- ↑ Kaufmann Goethe's painter Berlin 2003, p. 36. Her teacher Vogel taught her free of charge.

- ↑ Gardener: Kersting. Leipzig 1988, p. 86

- ^ Hermann Uhde (ed.): Memories of the painter Louise Seidler. 2nd edition, Propylaen, Berlin 1922, p. 68 digitized

- ↑ Charlotte de Latour [d. i. Louise Cortambert or Louis Aimé Martin]: The language of flowers, or symbolism of the plant kingdom. Berlin 1820

- ↑ Ulrike Krenzlin: On Georg Friedrich Forster's image of women in the interior. In: Georg Friedrich Kersting. V. Greifswald Romantic Conference in Güstrow. Greifswald 1986, p. 3

- ↑ Kaufmann Goethe's painter Berlin 2003, p. 56.

- ↑ Uhde Memoirs 1922 p. 72

- ↑ Thuringian Main State Archive Weimar A 11748 p. 70

- ↑ With Raphael the eyes of the Madonna and those of the baby Jesus are open and look at the viewer.