Eionaletherium

| Eionaletherium | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

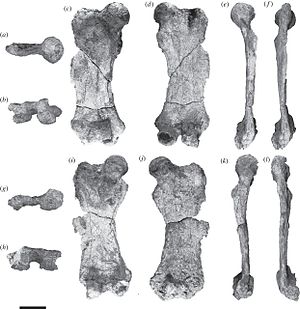

right and left femur of Eionaletherium , part of the holotype |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Upper Miocene | ||||||||||||

| 10.1 to 7 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Eionaletherium | ||||||||||||

| Rincón , McDonald , Solórzano , Flores & Ruiz-Ramoni , 2015 | ||||||||||||

Eionaletherium is an extinct genus of the sloth , which has so far only been proven for a few elements of the hind legs and other parts of the body skeleton of a single individual. These come from the Urumaco Formation of northwestern Venezuela , whichdatesto the Upper Miocene around 10 to 7 million years ago. The rock formation consists of deposits that go back to a river delta in the immediate vicinity of the then sea coast. The sloth genus is classified as a close relative of the group of Mylodontidae . As a special feature, unlike other Mylodonts, it had a very long lower leg. Whether this represents an adaptation to a life in a more watery environment is not clear due to the few findings. The first scientific description of Eionaletherium took place in 2015.

features

Eionaletherium was a medium-sized member of the family group of the Mylodontidae . It is known about some elements of the hind legs, individual vertebrae and ribs and about both shoulder blades. Based on the size of the finds, mainly the thigh bone , an animal with a body weight of around 1.1 t is inferred. The thigh bone reached a length of 51 cm. It was relatively wide and, typical for Mylodonts, flat like a board. In this it differs from the femora of the Megatheriidae , whose cross-section appeared to be slightly curved. The shaft had a rather straight course and showed only a slight twist, less than comparable with Mirandabradys . Both side edges were noticeably curved inwards. The head of the thigh bone was clearly distinguished by a short neck. Between this and the Great Rolling Hill there was a slight, saddle-like indentation. As with Mirandabradys, the Great Rolling Hill did not protrude beyond the base of the head. As a result, it was lower than, for example, Bolivartherium . The relatively small third trochanter (third rolling hillock) lay laterally below the large rolling hillock, slightly above the center of the shaft. This position was noticeably higher in comparison to Mirandabradys and Bolivartherium , in the latter it was also set further back and also significantly larger. The two lower, distant articulated rollers had an asymmetrical design so that the inner one was larger than the outer one. Unusually for Mylodontane, the tibia reached almost 87% of the length of the thighbone at 44 cm. As a rule, this value is below 65%, with some late representatives of the sloth group such as Glossotherium or Lestodon even 50% and less. The shaft of the tibia was oval shaped and also had a straight course. The upper and lower joint ends were roughly the same width. The fibula was not fused with the shin, but the feature is quite different in the Mylodonts.

Reference

All previously known finds of Eionaletherium were found in the Urumaco Formation in the Venezuelan state of Falcón in the north-west of the country. The Urumaco Formation is part of the Urumaco Sequence , a sequence of three lithostratigraphic units, the Socorro , Urumaco and Codore Formations , which cover part of the approximately 36,000 km² Falcón Basin . The three rock formations date from the Middle Miocene to the Lower Pliocene , with the Urumaco Formation belonging to the Upper Miocene and an age of around 10 to 7 million years. It is open on both sides of the Río Urumaco and reaches a thickness of 1700 m. The predominant deposits are various sand , clay / silt and limestone as well as individual coal layers . Informally, the Urumaco Formation is divided into three sub-units, the lower, middle and upper stratum. The middle stratum from which the finds originate is up to 755 m thick. It consists of a sequence of limestones, mighty, gray-colored clay / silt stones plus finely layered clay / silt stones enriched with organic residues and coal seams with numerous vertebrate remains . This sequence is partly interrupted by channel-like structures from 10 to 20 m thick locally, in which fine-grain, cross-layered sandstones are deposited, which mostly cover an area of erosion. These sandstones become finer-grained towards the top and then often have ripple structures. The entire deposition sequence goes back to an area near the coast that was under the influence of a river delta . The different sedimentary rocks reflect the prevalence of marine (limestone and clay / siltstone) or fluvial (sandstone) conditions in the course of the individual deposition phases.

The Urumaco sequence holds a large number of fossil finds. The first remains were discovered in the early 1950s when exploring for oil . This was followed by the first scientific expeditions to the area towards the end of the decade. The intensive research over the next few decades led to the fact that today more than 100 sites are known, which are spread over 60 different stratigraphic levels. A large part of the finds can be assigned to fish , among which sharks and rays dominate. In addition, reptiles such as turtles , crocodiles and occasional snakes have been identified, and there is also an extensive mammal fauna . Among the mammals, rodents , South American ungulates , manatees and joint animals appear, among others . Above all, the secondary articulated animals achieve an extremely high diversity, which is hardly inferior to that from much more southern areas of South America, such as the Pampa region or Mesopotamia , at this time. For example, representatives of the three major lines, the armadillos , the Pampatheriidae and the Glyptodontidae , have been identified from the group of armored animals . Among the tooth arms dominate sloths . At the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century, numerous new genera from the Urumaco sequence could be described here. The Urumaco formation includes Urumaquia as a representative of the large Megatheriidae as well as Mirandabradys , Bolivartherium and Urumacotherium from the line of the Mylodontidae and their immediate relatives. A special fact of taphonomy is the frequent transmission of limb elements in the sloths. Within the sloths of the Urumaco Formation, Eionaletherium is a rather smaller representative. Other Mylodonts are estimated to weigh between 1.7 t for Bolivartherium and 2.1 t for Urumacotherium . In terms of size, it was more similar to the Urumaquia, a member of Megatheria .

Paleobiology

Particularly noticeable is the very long tibia compared to the thighbone, which is not known in Mylodonts. The shin is around 87% of the length of the thigh bone. This value corresponds roughly to that of Thalassocnus from the group of the Nothrotheriidae (only individual members of the Megatheriidae have an even more balanced ratio of the two bones). In thalassocnus is a semi-aquatic living animal that numerous anatomical specified features. The extended lower leg section is interpreted here as an adaptation to paddling movements in the water, as it increases the leverage when swimming and makes propulsion easier. In principle, the geological conditions of the Urumaco Formation could also speak for a stronger adaptation of Eionaletherium to an aqueous environment and thus explain the relatively long tibia. However, the sloth genus lacks further adaptations such as those found in Thalassocnus . In the case of Eionaletherium, no bone swelling ( pachyostosis ) or bone compression ( osteosclerosis ) has been demonstrated, which often occurs in terrestrial vertebrates that are secondarily adapted to aquatic life and slow down buoyancy in the water. Eionaletherium also lacks the femoral head fossa (Fovea capitis femoris) on the femoral head, which speaks for poorly developed ligaments and thus only a poor ability to spread the leg and is atypical for semi-aquatic animals. Based on these findings, Eionaletherium must initially be viewed as a purely ground-dwelling living being.

Systematics

|

Possible internal systematics of the Mylodontoidea according to Rincón et al. 2015 based on traits of the hind legs

|

Eionaletherium is an extinct genus from the suborder of the sloths (Folivora). The sloths today comprise only two genera of small, tree-living animals, in their phylogenetic past they were very rich in shape and produced several lines of mostly ground-dwelling representatives. One of the most important lines is the Mylodontoidea , a very diverse group consisting of the Mylodontidae , the Scelidotheriidae and the Orophodontidae (the latter two are sometimes also managed as subfamilies within the Mylodontidae) according to the classical skeletal-anatomical view . The second major line of development can be found with the Megatherioidea . Molecular genetic studies supported by protein analyzes record a third large group, the megalocnoidea . The Mylodontoidea represent with the two-toed sloths ( Choloepus ) one of the two genera still existing today. Due to the characteristics of the hind limbs, such as the extremely flattened thigh bone and its laterally indented shaft, Eionaletherium is close to the Mylodontoidea. According to phylogenetic studies from 2015, the genus has closer relationships to forms such as Glossotherium or Bolivartherium, i.e. representatives of the Mylodontidae, than to other members of the superfamily . Eionaletherium could possibly also be attributed directly to the Mylodonts, although it is unclear whether it represents a particularly basal or more derived form due to the long lower legs. A study from the year 2019, on the other hand, sees it differently, which hived off egg etherium from the mylodonts. The problem with the investigation of the ancestral relationships is that in this case it is based on characteristics of the hind legs. As a result, representatives such as Hapalops or Analcimorphus appear as basal forms of the Mylodontoidea, while analyzes of the skull and teeth identify them as those of the Megatherioidea. It is likely that the morphology of the hind legs was very similar in very original representatives of the Megatherioidea and Mylodontoidea. For a more precise assessment, meaningful skull material must therefore be included, but that of Eionaletherium has not yet been available.

Discovery story

The fossil remains were discovered during investigations by the Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas (IVIC) in previously unexplored areas of the Urumaco Formation. They come from the "Charlie" site in the Buchivacoa district of the Venezuelan state of Falcón . The sediments in which the finds were embedded had deposited on the coast under the low-energy flow conditions of the water. Since all the bones of Eionaletherium were found on an area of only 2 m² and the area otherwise only contained turtle and crocodile remains, they are considered to belong to one individual. The first scientific description was made in 2015 by Ascanio D. Rincón and research colleagues. The holotype (copy number IVIC -P-2870) includes both femurs, the complete right tibia with fibula, the fragmented left tibia, remains of both shoulder blades, some vertebrae and ribs, and an ankle bone. The finds are kept in Caracas. The generic name Eionaletherium is made up of the Greek words ἠϊών ( eion "coast", "shore"), αλη ( ale "wandering around", "wandering around") and θηρίον ( thērion "animal"). It refers to the paleo-landscape where the sloth once lived. The only recognized species is E. tanycnemius . The species name tanycnemius in turn consists of the Greek terms τανη ( tany "long") and κνημἱς ( knemis "reaching from knee to ankle") and is a reference to the elongated shin.

literature

- Ascanio D. Rincón, H. Gregory McDonald, Andrés Solórzano, Mónica Núñez Flores, and Damián Ruiz-Ramoni: A new enigmatic Late Miocene mylodontoid sloth from northern South America. Royal Society Open Science 2, 2015, p. 140256, doi: 10.1098 / rsos.140256 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g Ascanio D. Rincón, H. Gregory McDonald, Andrés Solórzano, Mónica Núñez Flores and Damián Ruiz-Ramoni: A new enigmatic Late Miocene mylodontoid sloth from northern South America. Royal Society Open Science 2, 2015, p. 140256, doi: 10.1098 / rsos.140256

- ↑ Luis I. Quiroz and Carlos A. Jaramillo: Stratigraphy and sedimentary environments of Miocene shallow to marginal marine deposits in theUrumaco trough, Falcón Basin, Western Venezuela. In: Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra, Orangel A. Aguilera and Alfredo A. Carlini (eds.): Urumaco and Venezuelan palaeontology, the fossil record of the northern Neotropics. Indiana University Press 2010, pp. 153-172

- ↑ Omar J. Linares: Biostratigrafia de la fauna de mammiferos de las formaciones Socorro, Urumaco y Codore (Mioceno Medio-Plioceno Temprano) de la region de Urumaco, Falcón, Venezuela. Paleobiologia Neotropical 1, 2014, pp. 1-26

- ↑ Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra, Orangel A. Aguilera: Neogene vertebrates from Urumaco, Falcón State, Venezuela: diversity and significance. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 4, 2006, pp. 213-220

- ↑ Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra, Orangel A. Aguilera, Rodolfo Sánchez and Alfredo A. Carlini: The fossil vertebrate record of Venezuela of the last 65 million years. In: Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra, Orangel A. Aguilera and Alfredo A. Carlini (eds.): Urumaco and Venezuelan palaeontology, the fossil record of the northern Neotropics. Indiana University Press 2010, pp. 19-51

- ^ Alfredo A. Carlini, Diego Brandoni and Rodolfo Sánchez: First Megatherines (Xenarthra, Phyllophaga, Megatheriidae) from the Urumaco (late Miocene) and Codore (Pliocene) formations, Estado Falcón, Venezuela. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 4, 2006, pp. 269-278

- ^ Alfredo A. Carlini, Gustavo J. Scillato-Yané and Rodolfo Sánchez: New Mylodontoidea (Xenarthra, Phyllophaga) from the middle Miocene – Pliocene of Venezuela. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 4, 2006, pp. 255-267

- ^ Eli Amson, Christine Argot, H. Gregory McDonald, and Christian de Muizon: Osteology and Functional Morphology of the Hind Limb of the Marine Sloth Thalassocnus (Mammalia, Tardigrada). Journal of Mammal Evolution 2014, doi: 10.1007 / s10914-014-9274-5

- ↑ Luciano Varela, P. Sebastián Tambusso, H. Gregory McDonald and Richard A. Fariña: Phylogeny, Macroevolutionary Trends and Historical Biogeography of Sloths: Insights From a Bayesian Morphological Clock Analysis. Systematic Biology 68 (2), 2019, pp. 204-218

- ↑ Frédéric Delsuc, Melanie Kuch, Gillian C. Gibb, Emil Karpinski, Dirk Hackenberger, Paul Szpak, Jorge G. Martínez, Jim I. Mead, H. Gregory McDonald, Ross DE MacPhee, Guillaume Billet, Lionel Hautier and Hendrik N. Poinar : Ancient mitogenomes reveal the evolutionary history and biogeography of sloths. Current Biology 29 (12), 2019, pp. 2031-2042, doi: 10.1016 / j.cub.2019.05.043

- ↑ Samantha Presslee, Graham J. Slater, François Pujos, Analía M. Forasiepi, Roman Fischer, Kelly Molloy, Meaghan Mackie, Jesper V. Olsen, Alejandro Kramarz, Matías Taglioretti, Fernando Scaglia, Maximiliano Lezcano, José Luis Lanata, John Southon, Robert Feranec, Jonathan Bloch, Adam Hajduk, Fabiana M. Martin, Rodolfo Salas Gismondi, Marcelo Reguero, Christian de Muizon, Alex Greenwood, Brian T. Chait, Kirsty Penkman, Matthew Collins and Ross DE MacPhee: Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships. Nature Ecology & Evolution 3, 2019, pp. 1121-1130, doi: 10.1038 / s41559-019-0909-z

- ↑ Alberto Boscaini, François Pujos and Timothy J. Gaudin: A reappraisal of the phylogeny of Mylodontidae (Mammalia, Xenarthra) and the divergence of mylodontine and lestodontine sloths. Zoologica Scripta, 2019, doi: 10.1111 / zsc.12376

- ↑ Timothy J. Gaudin: Phylogenetic relationships among sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Tardigrada): the craniodental evidence. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 140, 2004, pp. 255-305