Iceberg model

The iceberg model is mainly used in applied psychology , pedagogy and special business administration to illustrate communication models that are based on the so-called 80/20 rule of the Pareto principle and are based (partly in a broader sense) on the general theory of Sigmund's personality Freud (1856–1939). The iceberg model is one of the essential pillars of communication theory for interpersonal communication .

The actual metaphor was first known in the 1930s by Ernest Hemingway as a description of his literary style. According to Hemingway, it is not necessary for an author to tell all the details of his main character. It is enough if, like an iceberg, one eighth can be seen above water.

An early German-language reception that explicitly leans the model on Freud can be found 35 years after Freud's death in Ruch / Zimbardo (1974). It should not be overlooked that Freud himself never used the metaphor of the iceberg - not even the word "iceberg" appears in his work. The dynamics of the psychological processes described by Freud can only be insufficiently illustrated with the image of a rigid iceberg.

Freud's theory of consciousness

Freud observed his patients and assumed that human actions in daily situations are only determined consciously to a small extent. This contradicted the previous view, according to which behavior can only be traced back to conscious thinking and rational action. This Freud divided the psyche in his id in three instances and took the view that the conscious portions of the ego (reality principle) only decide about which parts of it (the pleasure principle) and the superego (the Moralitätsprinzips) in which can be realized as a real world of perception. He thus points out the overly strong importance of the unconscious for human activity and supplements this with the areas of hidden subjectivity ( personality , feelings , conflicts ).

Freud, who saw the fears lying in the unconscious, repressed conflicts, traumatic experiences, drives and instincts repressed to different degrees, was also of the opinion that these imprints were dependent on earlier phases of development and impaired the next phases of development. He assumed that these processes were under the influence of the id and the superego and were only conscious for a short time before they sink back into the unconscious .

In order to make these perceptions conscious again, the censorship by the ego would have to be overcome, and so-called defense mechanisms would have to be understood by the individual so that an insight into the unconscious conflicts can take place. This process is critically dependent on the dynamics of the complex instances in the psyche. In general, however, the healthy ego succeeds in taking on the role of arbiter in the fundamental struggle between id and super-ego and negotiating a compromise in the event of a conflict, which often leads to the development of a symptom. At the same time, however, it depends on the experiences of the individual which dynamics develop in the context of this influence. This way of thinking is already reflected in an earlier model of the psyche in which he differentiated conscious, preconscious and unconscious content. Here Freud differentiates between the personality areas not in their function, but in their ability to become conscious of the individual. Most of the content of the psyche is anchored in the preconscious and in the unconscious. People are only aware of a small part of the content at the same time. The iceberg model serves as an illustrative analogy for the circumstances.

It is not clear who first attributed the image of an iceberg to Freud's stratification model. However, various authors later assigned his concept of the so-called I, i.e. the conscious areas of personality, to the smaller, visible part of a fictional iceberg above the surface of the water, and the subconscious areas, i.e. what Freud called the id and super-ego, the larger , part hidden under water.

The Pareto principle as the basis

The determination of an 80/20 distribution has many uses, with or without the visualization of the iceberg. The Pareto principle, named after the Italian engineer, sociologist and economist Vilfredo Pareto , states a constant probability distribution that many distributions in nature follow a scale law , very often a power law, i.e. a Pareto distribution. These proportions do not apply to the natural buoyancy behavior of an iceberg , but in psychology this is irrelevant for the sake of the concise formulation.

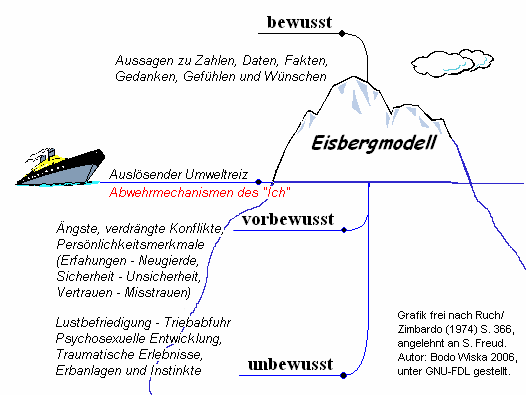

Iceberg model after Freud, by Ruch and Zimbardo

The iceberg model shown here according to Ruch / Zimbardo (1974), based on the three qualities of the psychic according to Freud, illustrates the dynamic between the three psychic parts of the personality. The three instances of the psyche according to Freud are not included.

The conscious parts of the personality, which are assigned to the rational behavior, are clearly recognizable in the upper area of the model. In interpersonal communication , as in intrapersonal communication (the so-called inner dialogue ), a proportion of importance of around 20 percent is assigned to these proportions .

The far greater proportion of motives for action, around 80 percent, lies in the area of the preconscious and unconscious areas. External events, in particular communication partners, but above all people towards themselves, do not perceive the hidden parts of the personality without analytical consideration.

Regarding the origin or the origin of the iceberg model (iceberg theory), the name Paul Watzlawick is occasionally mentioned . He has referred to this metaphor in numerous remarks; the original idea can be found in Freud's psychodynamic theories (see Philipp G. Zimbardo / Richard J. Gerrig: Psychologie, 18th edition, 2008), which of course have an influence on people's communication behavior. The originally mentioned numerical ratio of the model (10% visible above the surface, 90% hidden below the surface) has increasingly given way to the 20:80 distribution, as people with their desires, needs and behaviors have changed in the course of development. Often, 10 to 20% and 80 to 90% are spoken of, or a seventh and six sevenths. The 20:80 distribution is also known as the Pareto principle, which is also used in the areas of time and self-management and work methodology.

According to the theory applied by Watzlawick to communication, the visible area corresponds to the factual level (rational) and the invisible area to the relationship level (emotional); if the relationship level is disturbed, according to Watzlawick this inevitably has an impact on the content level.

Transferred iceberg models

In the following, a communication model with an (approximate) 80/20 distribution from different disciplines is to be presented, which additionally uses an iceberg model for clarification. This is followed by some essential general communication models, which, above all, descriptively follow the inner connection of Freud's core statement to smaller conscious and significantly larger unconscious parts of communication:

- The iceberg model of learning by Arnold and Schüßler 1998 assigns a so-called generation structure of receptive learning to the obvious area of learning psychology and thus the smaller, visible part of the iceberg. The so-called enabling structure is assigned to the more important and hidden part of the iceberg , in which learners work in a strongly action-oriented and explorative manner. Against the traditional tendency towards less didactic frontal teaching , the authors put their theory of the active and self-directed learner who does not find the goal of his learning process in mere specialist knowledge, but also and above all in the way in which he achieves this knowledge (see also: Learning through Teaching (LdL)). The methodology and didactics of how knowledge can be acquired independently are aimed at promoting both technical and social and methodological skills.

- In cultural studies, the iceberg is often used as a metaphor for a culture. This goes back to Charles E. Osgood . Accordingly, only a small part of a culture is visible (" Perceptas ": artifacts, verbal and non-verbal utterances) while the largest part (" Koncepta s": values, norms, attitudes, historical processes) are not visible.

- The cultural iceberg model is taken up in the area of corporate culture . The model goes back to a work by EH Schein , which, in the form of an iceberg, illustrates the connection between the visible and easily accessible manifestations of culture and the hidden parts of organizational behavior. The level model is intended to illustrate that a corporate culture analogous to the human psyche is only visible and consciously perceptible to a limited extent and that the much larger, hidden part contains paradigms that take a back seat to the rules and norms of behavior that are obviously communicated.

- Schratz / Steiner-Löffler have postulated a learning organization for school operations, for which they take up the iceberg model of organization (French / Bell 1990, p. 33). In terms of the development of school structures and teaching procedures, they point to the importance of hidden readiness, hidden interests and unconscious primary motivation , as well as the relevance of beliefs and values for fruitful organizational development .

- The analysis methods for the value of brands and trademarks offered by the market research companies Icon Added Value and GfK use a modified iceberg model with 80/20 distribution for the hierarchical recording of the value-determining influences on brand value (Andresen / Esch, 2001; Musiol et al., 2004 in) .

- In the area of project management , Hölzle and Grünig prove that you need social sensitivity for successful project management, since the real reasons for resource problems "under the water" are hidden from accurate and needs-based planning. This usually represents only a small part of the overall success of successful project management or the presentation of the concept, the milestones and results.

- In 2004, Enderle and Seidel presented the basis for further training in occupational medicine. The apparent rate of absenteeism due to illness or lack of motivation can be compared with the visible tip of an iceberg. Invisible, but very important for the company, is the potential of the employees present who are not brought in, who go about their work in a demotivated or ailing state but do not celebrate openly sick. Underperformance and absenteeism are also a symptom of operational problems. This corresponds to the approach of systemic coaching , in which a member of the company with behavioral problems is viewed as the " symptom carrier " for the overall system.

General communication models with Pareto distribution

Some important communication models with (also approximating) Pareto distribution do without, like Freud himself, the visualization by means of an iceberg. The corresponding stratification and weighting of the content becomes descriptively clear:

- The so-called Johari window of Jo seph air and Har ry I ngham, graphical field portfolio Four are shown in the personality and behavioral characteristics by means of a, has in three of four quadrants (ie to 75% of the area) is different conscious information that are communicated by a person. With the help of this model, the so-called blind spot in a person's self-image is illustrated, i.e. the deep-lying part of our personality that lies in the unconscious area of the psyche and that the agent himself is not aware of, but is recognizable to outsiders. Statements that are made as a public person and that we openly and openly show other people make up only a small proportion (approx. 25%) in the Johari window model.

- The so-called four ears of Schulz von Thun also divide the information content of a message into four parts. Only the first, semantic part of the message is therefore factually determined and unambiguous:

- The facts information includes the pure factual statements, facts and figures contained in a message. These are obvious.

- The appeal includes a wish or a call to action. This is usually clearly perceptible, even if it can often only be deciphered in context.

- The relationship note expresses or records how the relationship between the two people is felt. This level of the message is partly already unconsciously negotiated and is rarely part of the semantic statement at the same time.

- In self-revelation , the speaker conveys something about his or her basic self - image, his motives, values, emotions, etc. These are often information components that can only be made clear through a careful analysis of the context and the non-verbal elements as well as the history of an actor.

- According to the mime and university professor Samy Molcho, the non-verbal and largely unconscious parts of our communication cause over 80 percent of the reactions of our counterparts and thus form a direct reference to the psyche of people, their attitudes, instincts and values. The verbal, very conscious part of our communication therefore contains only a small part of the total information content of a personal statement with about 20 percent weight.

Web links

- Iceberg model according to Freud at encarta.msn ( Memento from May 18, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

swell

- ^ Death In the Afternoon. Scribner's, 1932, Chap. 16, 192.

- ↑ Floyd L. Ruch, Philip G. Zimbardo and others: Textbook of Psychology. An introduction for students of psychology, medicine, and education. Springer, Berlin 1974, ISBN 3-540-09884-4 , p. 366.

- ↑ Floyd L. Ruch, Philip G. Zimbardo and others: Textbook of Psychology. An introduction for students of psychology, medicine, and education. 1974, p. 367.

- ↑ Density of ice

- ^ Rolf Arnold, Ingeborg Schüßler: Change of learning cultures. Ideas and building blocks for lively learning. Scientific Book Society, 1998, ISBN 3-534-14168-7 , p. 11.

- ↑ Charles Osgood: culure - Its empirical and non-empirical character . In: Southwestern Journal of Anthropology . tape 7 , 1951, pp. 202-214 .

- ↑ S. Sackmann: Analyze corporate culture - develop - change. Luchterhand 2002, ISBN 3-472-05049-7 , p. 27.

- ↑ EH Schein: Organizational Culture. 1995, p. 25, Ehp.

- ↑ S. Sackmann: Success factor corporate culture. Gabler 2004, ISBN 3-409-14322-X , pp. 24/25.

- ↑ Michael Schratz, Ulrike Steiner-Löffler: The learning school. Beltz 1999, ISBN 3-407-25202-1 , pp. 123/124.

- ↑ Manfred Krafft (Ed.): Perspektiven der Kommunikationpolitik. Gabler 2005, ISBN 3-8349-0108-3 , p. 40.

- ^ Philipp Hölzle, Carolin Grünig: Project Management. Lead professionally - present successes. Haufe, 2006, p. 27.

- ^ Gerd Enderle, Hans-Joachim Seidel: course book occupational medicine. Course C. Continuing education. Urban & Fischer bei Elsevier, 2004, p. 40.

- ↑ Bernd Schmid: Systemic Coaching - Concepts and Procedures in Personality Counseling. Bergisch Gladbach 2004, ISBN 3-89797-029-5 .

- ↑ Joseph Luft: Introduction to group dynamics . Klett, Stuttgart 1971.

- ↑ Friedemann Schulz von Thun: Talking to one another . Volume 1: Disorders and Clarifications - General Psychology of Communication. 46th edition. (= Rowohlt-Taschenbuch. 17489). Reinbek near Hamburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-499-17489-6 .

- ↑ Samy Molcho, Thomas Klinger (photos): Everything about body language. Understand yourself and others better. Mosaic at Goldmann, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-442-39047-8 .