Communication model

A communication model or communication theory is the term used to describe scientific attempts to explain communication . In communication and media studies , these theoretical approaches should explain what communication is and how it works, and - in the form of models - make generalizable and theoretical relationships of the mass communication process recognizable.

Everyday theoretical communication models

The term everyday theory refers to the assumption that theories are also formed and applied in everyday life. In this sense, theory is not viewed as something separate from practice. The following sections summarize ideas and descriptions that are often mentioned when the subject of communication is discussed spontaneously and without reflection.

Communication as participation

The notion of communication as participation refers to the borrowing of the term communication from Latin ( communicatio ) and to the context of the meaning of sharing and sharing . Communication is seen here as the cultural process in which community emerges.

The idea of a common set of symbols

Some ideas about communication are based on the assumption that communication is only possible if there is a common set of symbols, the same language and a comparable socialization of the communication participants in advance . On closer inspection, these ideas turn out to be problematic. First of all, this does not answer the question of how signs and language are created.

In addition, the conception of word meanings (object of semantics ), including the conception of the stock of signs (object of semiotics ) and their use (object of pragmatics ), even with the same principles of order (object of syntax ) differ from person to person. This is particularly evident from the fact that extensive communication problems that require explanation can also exist between individuals with the same language.

The container metaphor

The container metaphor is associated with the idea of words or sentences as containers in which objectively determinable meanings are enclosed. In this metaphor, reception consists in taking the meanings from the containers as such. Meanings, sense and thoughts can be "packed" in a container according to this idea and then "unpacked" again. Naive ideas assume an identity of meanings.

The idea of communication as an exchange of information

In everyday terms, communication is described as an “exchange of information”. In other formulations the goal or the result of communication is seen in an “information flow”. In summary, this means the announcement or communication of knowledge, knowledge or experience. “Exchange” can be understood as reciprocity; “Flow” contains the idea of a direction that can also be bilateral. In the modeling behind these formulations, the communicating parties are disregarded. The focus is on what is called “information”.

Expression and impression models

With expression and impression models, one side of the communication process is strongly emphasized. The use of an expression and impression model is usually implicit in everyday life, that is, it is not made clear which model is currently used as the basis for claims about communication. If only one side is emphasized too much, the danger arises that the communication process is no longer viewed as a social process, i.e. a process encompassing both sides, in which expression and impression can only be thought of in relation to one another.

The model of expression

The expression model describes communication as a process that is essentially based on “expressing” “content” using drawing processes and media. The reception - that is, the self - perception and processing related to the producer using drawing processes - plays a secondary or subordinate role in these models.

In the following, communication is seen as something that begins with “expressing something” using drawing processes, that is, with speaking, writing, producing a program. In particularly strong expression models, the producer (the person who "expresses" something) does not refer to potential or real recipients. In extreme cases, “expressing something” is equated with communication.

The problems with an expression model that is too strong is that this model does not offer any way of describing the recipient as communicating. According to the extreme expression model, for example, a television viewer does not communicate with the people appearing on television as long as he does not give any feedback to the current program, that is, as long as he himself does not “express” anything that those appearing on television cannot perceive. A cinema-goer cannot communicate with the actors in the film while they are in the cinema. According to the strong expression model, the reader of a newspaper does not communicate with the authors of the text while reading the texts.

The impression model

An impression model is used less often, with which communication is described as a process that is essentially based on the fact that “contents” arise through reception (through external perception of what is produced using sign processes) and are processed with the help of individual world theory (world view). As a result, communication is seen as something that begins with reception. In particularly strong impression models, the recipient does not refer to the potential or real producer. In an extreme sequence, reception (the processing of what is perceived as a sign or as meaningful) is equated with communication.

An impression model that is too strong can lead to the concept of communication being expanded too far as a result of neglecting the reference to a producer. This would be the case if perception is viewed as communication with the environment.

Scientific communication models

Most scientific communication models are illustrations of the communication process in which either individual process elements and their structure (structural models), the course of the process (flow models), the tasks and services of the process (functional models) or defining features (classification models) are shown. Another distinction is made between process models, system models and impact hypotheses. In these three basic forms, linear models, circular models, media effect models and sociological models occur, whereby the differentiation and increasing specification of the models follow an internal scientific development logic.

Descriptive models

The political scientist Harold Dwight Lasswell formulated a word model based on his Lasswell formula “Who says what in which channel to whom with what effect?” In 1948 in an essay in which he dealt with the structural-functional analysis of communication processes. In this way, in the sequence of the five questions, he created an order principle for describing the processes and at the same time defined the research areas of communication studies ( communicator research , media content research , media analysis , media usage research and media impact research ).

The communication model of Bruce H. Westley and Malcolm S. MacLean (1957) was developed in the tradition of gatekeeper research. From a system-theoretical point of view, the process of messaging is represented as a multiple selective and dynamically linked process.

The communication model by John W. Riley and Matilda White Riley (1959) deals with the social interdependence of communication partners. Communicator and recipient belong to social groups (e.g. primary groups ) that mediate communication and thus influence communication behavior. The gatekeeper properties in the mass media, the type of selective perception , the quality of the interpretation, the retention of a message and the recipient's reaction to it are taken into account. With regard to the media effect , this model sees mass communication as an element of the entire social system and a factor alongside other influences on individual and social behavior. Mass communication and social systems influence each other. Sociological and socio-psychological issues are included in mass communication research in that communicator and recipient are seen as elements of two social structures that are mutually dependent on one another.

The field schema of mass communication by Gerhard Maletzke (1963) is a socio-psychologically oriented model that takes into account referential and interactive mechanisms of communication. Four positions in the mass media process are named: the communicator, the statement , the medium and the recipient. Each position influences the other.

The materialistic communication model by Wulf D. Hund (1976) shows the connection between mass communication and the socio-economic conditions of a capitalist organized society - in the sense of materialistic social theory. It is assumed that the communicator, as a news production company, produces his means of production, i.e. the modern mass media and the statements conveyed through them, primarily as goods and uses them for capital utilization.

Messaging models

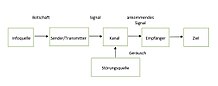

In many cases, communication is described using the so-called transmitter-receiver model . This model emerged from the mathematical theory of communication by the two mathematicians Warren Weaver and Claude E. Shannon .

The information technology communication model is a comparatively poor model. A "source of information" (information source) selects a " message " (message) from that of written or spoken signs can be made. The " transmitter " (transmitter) transforms it into a signal , which via a communication channel to a " receiver " (receiver) is transmitted. By sources of interference (noise source) the original signals can be distorted.

The Shannon-Weaver model is based on technical aspects of signal transmission . Information has nothing to do with meaning here , but refers to physically determinable signal quantities and processes, and it deals with the probability of such physically determinable events (signals and signal combinations) occurring. Examples are the telephone , telegraphy or radio . Therefore this model is not suitable for describing social communication processes.

Compare the communication model from Friedemann Schulz von Thun .

Media impact models

SR and SOR models

The transmitter-receiver model (also Hypodermic Needle Concept , Transmission Belt Theory or Magic Bullet Theory ; 1920s) combines the stimulus-response model with the theory of mass society . According to this model, every individual is reached in the same way by stimuli via mass media and perceives them in the same way, whereby a similar reaction is achieved in all individuals. The content of the communication and the direction of the effect (the effect) are equated in the sense of the stimulus-response model. The mass media are seen as powerful instruments of propaganda and manipulation that can be used to control entire societies. The simple idea of a mechanistic stimulus-reaction mode of action of the mass media could not hold up; it has even been doubted since the 1990s that this model found its way into the communication science discourse at the beginning of the 20th century - rather, it subsequently served to illustrate a tendency to ever differentiated concepts in the history of communication science models.

The stimulus-response model, i.e. the equation of content and effect, was discarded in both psychology and media studies, since knowledge of the stimulus does not indicate a corresponding reaction on the part of the recipient. The SR theory was expanded to the SOR concept (based on the SOR paradigm ), whereby the individual as an "object" as an effect-relevant factor in attempts at influencing moved into the center of attention. The model was used in the sense of an upgrading of the individual psychological disposition in the mass communication process, especially in the 1940s in attitude research , for example by the research group around Carl I. Hovland .

Two-stage models

The communication model according to Lazarsfeld is based on an investigation of the presidential election campaign in the USA of 1940 by the sociologists Paul F. Lazarsfeld , Bernard Berelson and Hazel Gaudet in their election study The People's Choice (1944). In it they explored the processes of opinion formation among voters, based on the prevailing idea of the strong effects of the mass media ( press and radio ) at the time. Instead, the decision of the voters was determined less by the influence of the media than by personal contact with other people. Media was used rather selectively, by turning to certain media offers that support one's own opinion. The election campaign therefore only reached those voters who had already made up their minds in favor of a party and strengthened their already existing attitudes. The researchers came to the conclusion: ideas flow from the media to the opinion leaders and from them to the less active sections of the population. This hypothesis of the two -step flow hypothesis shows a departure from the theory of the omnipotent media, since the opinion leader was placed between the media and the recipient as an additional selection authority. The effects of the media depend on conditions that are in the social context - i.e. in principle outside of the media itself. Nevertheless, as a result of traditional stimulus-response thinking, no distinction was made between turning to media content and influencing attitudes change; d. That is, the processes of transmission and diffusion were equated with the process of influencing (persuasion).

A further development of the simple notion of a poorly differentiated two-stage process to a multi-step flow model took place in the 1950s through the realization that opinion leaders are themselves more influenced by personal contacts than by the media, i. In other words, there are “opinion leaders of opinion leaders”.

The separation of opinion leaders , as someone who only passes on information, and non-leaders , as the sole recipient of information, could not be maintained. According to the so-called opinion sharing model according to Verling C. Troldahl and Robert van Dam (1965), the transfer of information and opinions disseminated in the mass media in the context of personal conversations is not one-sided, but reciprocal. In the course of the mass communicative diffusion process (i.e. the dissemination of information via mass media) there is a group of people ( opinion leaders or opinion givers ) who are well informed and interested and who pass on topic-specific information and opinions within interpersonal communication processes , and such people who want to receive this from interlocutors (opinion askers) - the two groups of people influence each other and thus alternately become opinion givers and opinion askers . A third group, the opinion-avoiders , does not engage in either of the two interactive communication activities and is also less exposed to the mass media.

The American Journalism scientist David M. White transferred in 1950 to approach the social psychologist Kurt Lewin , it accordingly in almost all social institutions strategically important doors, locks or switching stations are where (individual makers gatekeeper or "lock-keeper") occupy key positions on the process of message selection and thus developed the gatekeeper approach . To do this, White examined the selection behavior of agency reports by an editor of a daily newspaper in a small American town. White postulated two reasons for the editor's decision to publish: On the one hand, certain reports would not be published due to individual decision-making criteria because they were classified as not interesting, poorly written or propagandistic . On the other hand, the publication decision is based on formal criteria, such as the length of the agency report or the time of transmission to the editorial office. The gatekeeper research approach criticized the emphasis on the individual selection criteria of journalists and the neglect of institutional and technical influences on news selection .

Theory of the ineffectiveness of the media

In 1960, the American communication scientist Joseph Klapper adopted the knowledge of the “two-stage flow of communication” in his reinforcement thesis, according to which the mass media cannot bring about a change in attitudes, but rather reinforce existing attitudes. Klapper relies on the theory of cognitive dissonance of the psychologist Leon Festinger . Festinger assumed that the feeling of contradictions in the knowledge and opinion of people is perceived as unpleasant and that individuals try to reduce or avoid these contradictions. The derived hypothesis of a selective communication usage (selective exposure) states the respect media use that individuals actively seek the information that supported their beliefs and avoided their beliefs contradictory information. This approach continues to influence research into advertising effectiveness to this day .

Cognitive media effects

In the knowledge gap hypothesis (Knowledge-Gap) by Phillip J. Tichenor , George A. Donohue and Clarice N. Olien takes (1970) - similar to the cultivation theory - the concept of media literacy an important role. In this approach, it is assumed that knowledge conveyed through the media is used in different ways by different parts of the population: People with a higher socio-economic status or a higher formal education process information offered by the mass media better and faster than those who have less of these properties Extent exist. As a result of increased media offers, the “knowledge gap” between the two parts of the population is tending to grow.

In the 1970s, Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann formulated a concept with the theory of the spiral of silence in which the media - in contrast to the amplifier hypothesis - are again assumed to have strong effects. According to Noelle-Neumann, in order to avoid social isolation , people tend to withhold their opinion when it contradicts a presumed majority opinion. On the other hand, if people believe that they represent the majority opinion, they tend to express their opinion publicly. The (apparently) prevailing opinion is expressed more and more frequently, the (apparently) weaker opinion less and less. The mass media convey a picture of the presumed majority opinion and assume an articulation function by conveying linguistic representation patterns for apparently predominant viewpoints - a relief to be able to represent this viewpoint in public.

In the agenda-setting approach of the two communication scientists Maxwell E. McCombs and Donald L. Shaw (1972), as in the theory of the spiral of silence, strong media effects are assumed: the media generate public discourse through the selection of topics and give them importance the topics that are of high priority in the reporting are also considered important by the recipients.

In their agenda building approach (1981), the two sociologists Gladys E. Lang and Kurt Lang assume that the media agenda itself is the result of selection and construction processes. Media productions such as press conferences , exclusive interviews, etc. The like, which are cleverly initiated by PR and advertising professionals , determine the media agenda even before it can influence the public setting of issues.

See also

literature

- Uli Bernhard, Holger Ihle: New Media - New Models? Considerations for future communication science modeling. In: Studies in Communication Sciences. Journal of the Swiss Association of Communication and Media Research. Vol. 8, N. 2, 2008, pp. 221-250.

- Roland Burkart , Walter Hömberg (Ed.): Communication theories. Braumüller, Vienna 1992, ISBN 3-7003-0956-2 .

- Horst Völz : That is information. Shaker Verlag, Aachen 2017, ISBN 978-3-8440-5587-0 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ This modeling is in turn based on a dualistic view in which there is a separation between an inner area, which is only accessible to the self, and an outer area, which in principle is accessible to everyone.

- ^ Siegfried J. Schmidt, Guido Zurstiege: Orientation Communication Studies. What she can do, what she wants. Rowohlt TB, Reinbek near Hamburg 2000, p. 57.

- ↑ Uli Bernhard, Holger Ihle: New Media - New Models? Considerations for future communication-scientific modeling. In: Journal of the Swiss Association of Communication and Media Research. Vol. 8, N. 2, 2008, pp. 238f.

- ↑ Uli Bernhard, Holger Ihle: New Media - New Models? Considerations for future communication-scientific modeling. In: Studies in Communication Sciences. Journal of the Swiss Association of Communication and Media Research. Vol. 8, N. 2, 2008, pp. 231-238.

- ^ Harold D. Lasswell: The Structure and Function of Communication in Society. In: Lyman Bryson (Ed.): The Communication of Ideas. A Series of Addresses. Harper, New York / London 1948, pp. 37-51.

- ↑ SJ Schmidt, G. Zurstiege: Orientation Communication Science. 2000, p. 58f.

- ↑ Bruce H. Westley, Malcolm S. MacLean Jr.: A Conceptual Model for Communication Research. In: Journalism Quarterly. 34th year 1957, pp. 31-38.

- ↑ Roland Burkart: Communication Science: Basics and Problem Areas. 4th edition. Böhlau, Wien et al. 2002, ISBN 3-205-99420-5 , p. 494.

- ^ John W. Riley, Mathilda W. Riley : Mass Communication and the Social System. In: Robert K. Merton, Leonard Broom, Leonard S. Cottrell: Sociology Today: Problems and Prospects. New York 1959, pp. 537-578.

- ^ Roland Burkart: Communication Science. 2002, p. 497f.

- ↑ Gerhard Maletzke: Psychology of mass communication. Theory and systematics. Verlag Hans-Bredow-Institut, Hamburg 1978 (first 1963).

- ↑ SJ Schmidt, G. Zurstiege: Orientation Communication Science. 2000, p. 64f.

- ^ Wulf D. Hund: Ware news and information fetish. On the theory of social communication. Darmstadt / Neuwied 1976.

- ^ Roland Burkart: Communication Science. 2002, p. 512.

- ^ Claude E Shannon , Warren Weaver : The mathematical theory of communication. University of Illinois Press, Urbana 1949. In summary: Dieter Krallmann, Andreas Ziemann: The information theory of Claude E. Shannon. in: ders .: Basic course in communication science: with an in-depth hypertext program on the Internet. (= UTB for science. 2249). Fink, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-7705-3595-2 , pp. 21-34.

- ^ Klaus Beck: Communication Science . Ed .: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft. 4th edition. 2015, ISBN 978-3-8252-4370-8 , pp. 20 .

- ↑ In this context, Claude E Shannon used the term information to describe his mathematical models. The mathematical theory of communication is therefore now called information theory. Through this use, the concept of information was greatly modified, see z. B: Peter Janich : What is information? 1st edition. Suhrkamp Verlag, 2006, pp. 58-60.

- ↑ SJ Schmidt, G. Zurstiege: Orientation Communication Science. 2000, p. 63f.

- ^ Roland Burkart: Communication Science. 2002, p. 195.

- ^ Brosius and Esser 1998.

- ^ Roland Burkart: Communication Science. 2002, p. 196f.

- ^ Paul F. Lazarsfeld, Bernard Berelson, Hazel Gaudet: The People's Choice. How the Voter Makes up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign. 2nd Edition. Columbia University Press, New York 1948 (first 1944).

- ↑ SJ Schmidt, G. Zurstiege: Orientation Communication Science. 2000, pp. 97f.

- ↑ Karsten Renckstorf: On the hypothesis of the “two-step flow” of mass communication. In: radio and television. 3-4, 1970, pp. 317f.

- ^ Roland Burkart: Communication Science. 2002, p. 211.

- ↑ Verling C. Troldahl, Robert Van Dam: Face-to-Face Communication About Major Topics in the News. In: Public Opinion Quarterly. 29/1965, pp. 626-634.

- ^ Roland Burkart: Communication Science. 2002, p. 212f.

- ^ David Manning White: The "Gate Keeper": A Case Study in the Selection of News. In: Journalism Quarterly. Vol. 27, issue 3/1950, pp. 383-390.

- ↑ SJ Schmidt, G. Zurstiege: Orientation Communication Science. 2000, p. 128f.

- ^ Joseph T. Klapper: Effects of Mass Communications. Toronto 1960.

- ↑ SJ Schmidt, G. Zurstiege: Orientation Communication Science. 2000, p. 99.

- ↑ Phillip J. Tichenor, George A. Donohue, Clarice N. Olien: Mass Media and the Differential Growth in Knowledge. In: Public Opinion Quarterly. 34, 2, 1970, pp. 159-170.

- ↑ SJ Schmidt, G. Zurstiege: Orientation Communication Science. 2000, p. 109f.

- ^ Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann: The spiral of silence. About the emergence of public opinion. 1977.

- ↑ SJ Schmidt, G. Zurstiege: Orientation Communication Science. 2000, p. 100f.

- ^ Maxwell E. McCombs, Donald L. Shaw: The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media. In: Public Opinion Quarterly. 36/1972, pp. 176-187.

- ↑ SJ Schmidt, G. Zurstiege: Orientation Communication Science. 2000, pp. 101f.

- ↑ Gladys E. Lang, Kurt Lang: Watergate: An Exploration of the Agenda Building Process. In: GC Wilhoit, H. DeBock (Ed.): Mass Communication Review Yearbook. Vol. 2, 1981, pp. 447-468.

- ↑ SJ Schmidt, G. Zurstiege: Orientation Communication Science. 2000, p. 103.