Misery alcoholism

The term misery alcoholism was coined in the 20th century and is used in literature to describe alcoholism as a mass phenomenon among the lower classes of the population as a result of poverty and pauperism , especially in connection with the social upheavals of the industrial revolution . Some historians disapprove of the use of this term as misleading because there is no causality between alcoholism and industrialization . The opposite term is affluence alcoholism .

Historical background

Alcoholic beverages were already everyday drinks for all strata of the population in Europe in the Middle Ages , but in the form of wine and beer with a low alcohol content . One reason for this was that the drinking water was often contaminated and therefore could not be drunk straight. In addition, wine and beer were not considered luxury foods , but fortifying foods . Beer brewing in Germany has been declining since the 17th century .

After the Wars of Liberation (1813–1815), brandy became significantly cheaper than beer thanks to new and better industrial production processes and the use of potatoes as a raw material. The largest potato growing areas in the north and east of Germany became centers of the potato schnapps distillery, mostly operated by aristocratic landowners. The cheap schnapps became an everyday drink for large parts of the population. The term brandy plague was coined by contemporaries for mass consumption .

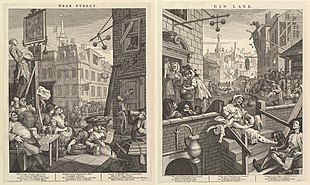

There was a similar development in England . There the beer tax was increased in 1694, so that the lower classes of the population could only afford the cheaper brandy. Per capita consumption increased tenfold by 1750; At that time, an adult Londoner drank around 63 liters per year according to statistics. In 1751 the tax on spirits was increased and consumption fell sharply. “The basic constellation of the gin epidemic should be repeated many times over: Ireland , USA, Germany, Scandinavia . Only the countries with an unbroken tradition of viewing wine or beer as food, such as Italy or Bavaria , show themselves to be immune ”. In Prussia , annual schnapps consumption increased fivefold from 1800 to 1830 to almost 25 liters per capita, which corresponds to over 40 liters in relation to the adult population.

The sharp increase in the consumption of spirits coincided with the dissolution of the traditional class society in Europe, which until the 18th century had assigned everyone a permanent place in the social structure. "Never in European history has life been so miserable (...) as in the decades that preceded industrialization."

An important prerequisite for industrialization was the so-called population explosion from the middle of the 18th century. While the death rate was about as high as the birth rate until the 18th century , the birth rate was now significantly higher. This inevitably increased the need for food. The restrictions on the guilds fell away, and freedom of trade and freedom of residence were introduced. The impoverished rural population streamed into the cities ( rural exodus ) and was available as cheap labor for the newly emerging factories . A worker's wages weren't enough to support a family, so women and children had to help. The widespread misery of working-class families in the cities of the 19th century is also known as pauperism .

Employees who performed particularly strenuous jobs, often had to work overtime or worked under extreme conditions, such as the workers in the foundry at Krupp , received a daily ration of schnapps from their employer.

After the American Temperance Society was founded in Boston in 1826 , similar associations of the abstinence movement followed in Europe, first in Great Britain and a short time later in the German Confederation . The first wave of “abstinence” ended in the middle of the 19th century, before alcoholism again became a publicly discussed topic decades later and was classified as a disease by medical professionals.

Industrialization theory

A link between the social situation of the individual and alcoholism has been in Germany since the pre-March debate. The theory that the increased alcohol consumption of the lower strata of the population in the 18th and 19th centuries was misery alcoholism , which was a direct result of the industrialization process, goes back above all to the social theories of Marxism . “(…) The description of misery alcoholism and the necessary countermeasures became a topic for political scientists and other medical laypeople such as Robert von Mohl or Friedrich Engels . (...) Engels - like later parts of the SPD - saw the consumption of alcohol as a symptom of industrial capitalism, i. H. a necessary consequence of the (...) impoverishment of the proletariat resulting from the capitalist relations of production . Overcoming capitalism would inevitably have led to the elimination of alcoholism. "

Engels' report from 1845, entitled The Situation of the Working Class in England , had a major influence on the position of the German labor movement and the SPD on the alcohol consumption of the working class. According to Engels, the poor living conditions of the proletariat almost inevitably led to alcoholism. Parts of the SPD also saw alcoholism primarily as an obstacle in the class struggle . This position was vehemently represented by the German Workers' Abstinence Association (DAAB), which was founded in 1903 and had 1,300 members in 1905. He demanded complete abstinence and, according to the statute, wanted to "promote the liberation struggle of the working class (...) by combating alcohol consumption and drinking habits within the working class". The DAAB even described alcohol as a means deliberately used by the bourgeoisie against the proletariat and coined the term "alcohol capital".

In this perspective, it is assumed that many manufacturers deliberately sold high-proof alcohol to their workers in order to make them both docile and more efficient. One author says: “Achievement and obedience - that too many factory owners bought with alcohol. (...) The new order was easier to enforce against slightly intoxicated workers. "

"The assessments of the phenomenon of brandy plague as misery alcoholism at the time of the emerging industrialization assume a causal chain of industrial factory work, poor working and living conditions, mass poverty and alcoholism."

Misery alcoholism also became a literary topos among proponents of naturalism such as Émile Zola .

Opposing positions

The theory of wretched alcoholism among urban industrial workers in the 19th century is controversial among historians. Above all, the assumed causal connection between industrialization and alcoholism or increasing alcohol consumption is criticized. Heinrich Tappe writes: "The brandy plague preceded industrialization in Germany and cannot be associated with it either in terms of demand or production structures." After 1800, cheap potato schnapps was initially an everyday drink among the population in the rural regions of the north - and East Germany, and from these regions came the mass of early factory workers who maintained their drinking habits in the cities. Pauperism also preceded the Industrial Revolution.

Gunther Hirschfelder is of the opinion that even before industrialization, a relatively large amount of alcohol was drunk in craft and in factories . What was new in the 19th century was that brandy had replaced wine and beer. Using sources, he examined the alcohol consumption of workers in Manchester and Aachen and came to the conclusion that the term misery drinking is above all a common catchphrase and speaks of a “myth” in connection with industrial workers. “In the context of society as a whole, it must be noted that it was by no means artisans or workers who drank the most in pre-industrial or early industrial times; The absolute top positions in this respect were held by wealthy male merchants and middle-aged wealthy citizens. "

Also Ulrich Wyrwa contradicts the theory of alcoholism misery of the workers in the 19th century and concludes: "The alcohol consumption of the workers is not a symptom of impoverishment and demoralization, but an element of their culture and lifestyle. (...) Despite want and need, the workers were able to create situations of leisure and enjoyment, they were not just the helpless victims of industrialization (...) ”.

According to Hasso Spode, there is no direct connection between the public discussion of an "alcohol problem" and the amount of alcohol actually consumed by the population; He speaks of four "thematization conjunctions" in Central Europe since the Middle Ages , the first in the 16th century, the second around 1800, the third in the second third of the 19th century and the last at the end of the 19th century. “The thematization cycles show no correlation with the absolute level of consumption. Instead, they expressed a change in social attitudes towards dealing with alcoholic beverages. (...) Since around 1800 (...) it has been a matter of global phenomena that were not only, but primarily, successful in Protestant cultures. "

literature

- Gunther Hirschfelder : Alcohol Consumption at the Beginning of the Industrial Age 1700–1850. Comparative studies on social and cultural change . 2 volumes (Vol. 1: The Manchester region . Vol. 2: The Aachen region ). Böhlau, Cologne 2003-2004, ISBN 3-412-15301-X (also: Bonn, Univ., Habil.-Schr., 2000).

- James Roberts: The Alcohol Consumption of German Workers in the 19th Century . In: History and Society . 6, H. 2, 1980, ISSN 0340-613X , pp. 220-242.

- Hasso Spode : The power of drunkenness. Cultural and social history of alcohol in Germany . 2nd completely revised edition. Leske and Budrich, Opladen 1996, ISBN 3-8100-1709-4 .

- Heinrich Tappe: On the way to modern alcohol culture. Alcohol production, drinking behavior and temperance movement in Germany from the early 19th century to the First World War . Steiner, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-515-06142-8 ( Studies on the History of Everyday Life 12), (At the same time: Münster (Westphalia), Univ., Diss., 1992).

- Ulrich Wyrwa: Brandy and “real” beer. The drinking culture of the Hamburg workers in the 19th century . Junius, Hamburg 1990, ISBN 3-88506-507-X ( Social History Library at Junius 7).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Gunther Hirschfelder, Der Mythos vom Elenddrinken, in: LpB (ed.), The citizen in the state. Issue 4/2002, food culture . Eating and drinking in transition , pp. 219–225.

- ↑ a b c Ronald Schenkel: Alcohol - once food and part of wages, now frowned upon. HR Today , December 2007, archived from the original on November 14, 2010 ; accessed on January 11, 2016 (original website no longer available).

- ^ A b c d e Heinrich Tappe, Alcohol Consumption in Germany. Development, influencing factors and control mechanisms of drinking behavior in the 19th and 20th centuries, in: Bürger im Staat. Food culture booklet, 4/2002, pp. 213-218.

- ^ A b c Hasso Spode: Art. Alcoholic beverages in Thomas Hengartner / Christoph Maria Merki , luxury foods. A cultural history handbook, 2001, pp. 55 ff.

- ^ Hasso Spode: Art. Alcoholic beverages in Thomas Hengartner / Christoph Maria Merki, luxury foods. A cultural history handbook, 2001, p. 56.

- ^ Hasso Spode: Art. Alcoholic beverages in Thomas Hengartner / Christoph Maria Merki, luxury foods. A cultural history handbook, 2001, p. 55.

- ↑ Wickard pulse, stress, working conditions and the consumption of alcohol. Theoretical constructions and empirical findings, 2002, p. 18.

- ↑ a b Markus Wollina: "People who are saturated with alcohol" SPD and "Alcohol Question", 1890–1907. (PDF 92 kB) labour.net , archived from the original ; accessed on January 11, 2016 (original website no longer available).

- ↑ Sylvia Kloppe, The Social Construction of Addiction Disease, 2004, p. 164.

- ↑ Ulrich Wyrwa: Brandy and ›real‹ beer. (Summary). University of Potsdam, archived from the original on December 11, 2008 ; accessed on April 8, 2019 (original website no longer available).

- ↑ Hasso Spode: On the change in social attitudes to the subject of 'alcohol'. (PDF 36 kB) German Central Office for Addiction Issues (DHS), November 12, 2007, accessed on January 11, 2016 (keynote speech at the DHS specialist conference November 12-14, 2007 on the topic: Alcohol - New strategies for an old problem?) .