Owl fried egg

As Eulenspiegelei is called a trickery prank in the style of Till Eulenspiegel , which someone plays on another by taking his instructions literally and carrying them out. In addition, this term is also used to denote an artistic form of representation that is derived from the historical or literary figure of Eulenspiegel. The literary, visual and musical design of Eulenspiegel's rascal pranks has been given different meanings. They range from trivial exposure (especially in carnival cultures ) to esoteric appreciation of the mischievous soul .

history

Around 1300 a Thyl Ulenspiegel, who was born in the Braunschweig area, is said to have lived, according to which the later recorded stories are told. The Eulenspiegel-Volksbuch, printed in Strasbourg in 1515, contains 96 short episodes from Eulenspiegel's life. Together they result in a loose representation of the life course for a thoroughly tragic figure who - already baptized fatefully and constantly dependent on the clever manipulation of contemporaries - ultimately does not escape the dishonorable burial and denigration of his grave.

A similar rogue became known in the Turkish-Oriental region from the same time: Nasreddin Hodscha. Sebastian Brant's “Ship of Fools” (1494) represents another variant of the fool's literature. Don Quixote is the Spanish version of the fool's representation. The Lale book of shield bourgeoisie also belongs to the series of foolish mirrors.

Fischart's “Eulenspiegel Reimenweiss” (1572) degenerates the hero into “Grobianus”. Hans Sachs has processed Till Eulenspiegel's folk book in various swans, master songs and carnival games. In Jakob Ayrer's Singspiel “Von dem Eulenspiegel with the merchant and pipe maker” (1618) the figure of the trivial buffoon is fully achieved.

In his Latin Eulenspiegel poem of 1558, J. van Neem also failed to overcome the level of coarse antics. That is why in the centuries that followed, priority was given to the subjects of higher quality life narratives. Don Quichote, Simplizissimus, Agathon, Wilhelm Meister, and Good-for-nothing are the names of the heroes in these stories by Cervantes, Grimmelshausen, Wieland, Goethe and Eichendorff.

Wieland's "Goldener Spiegel" is a further variant of the fried eggs, which sees itself as a "fairytale mirror". Münchhausen's fairy tales also belong in the tradition of alternative fools' mirrors.

With the turn into the political, some poets of so-called Junge Deutschland found the Eulenspiegel figure immediately attractive again. B. Oettinger "The confiscated Eulenspiegel". The figure of the fool was celebrated as a hero of democratic freedom.

Grabbe came up with the idea of glorifying Eulenspiegel as a hero of romantic freedom. Charles de Coster completed this idea in his novel “La Légende de Ulenspiegel” (1868). With this in mind, a number of Eulenspiegel operas were created. Richard Strauss wrote probably the most important opera on the Eulenspiegel theme with his Eulenspiegel fragment in 1895. Charles de Coster's Eulenspiegel novel has been transformed into an opera by Walter Braunfels .

In Gerhart Hauptmann's work , an Eulenspiegel story (1919) depicting the post-war period has become a time-critical epic. In 1933 M. Jahn again dealt lyrically with Eulenspiegel. The "Eulenspiegel stories" by Bertolt Brecht (1948) also come from the same period. In general, in these works the tendency of Young Germany to underlay Eulenspiegel with democratic motives is continued.

Erich Kästner edited the Eulenspiegelstoff in a children's book. After his books were burned in 1933 and he was banned from writing, he had his “Till Eulenspiegel” published in Switzerland in 1938. If one could no longer offer the deluded adults literary truth, one could at least try it with the children.

In 1973 Christa and Gerhard Wolf created a film script on the subject of Eulenspiegelei. P. Rosel finally moves the setting to America: "Ulenspiegel America" (1976). In 1983 W. Konold and E. Sauter followed up Richard Strauss's attempts to bring Eulenspiegel into ballet (1983).

Finally, Wolfgang Abelard created a book of Eulenspiegel that depicts Eulenspiegel as the reincarnation of an "old" soul (2009). In the context of spiritual reincarnation theorems it is assumed that Eulenspiegel is a soul that has lived hundreds of times before. The meaning of their Eulenspiegel existence lies in mirroring: by holding in front of the superficiality in various symbols and allegories, the gaze is directed to the truly essential.

Concepts

Volksbuch

Probably the first major concept of Eulenspiegelei was often attributed to Hermann Bote in the 1970s . A kind of biography of the hero is presented in 96 “histories”. It starts with the story, "How Till Eulenspiegel was born, was baptized three times in one day and who his godparents were". The editions of the 20th century are mostly available in standard High German translation. The present excerpt follows the edition by Lindow (1978).

“The 33rd Histori

says how Ulenspiegel ate at Bumberg umb Gelt

Ulenspiegel earned a single measure of Bamberg with lists, when he came from Nuremberg and was almost hungry and there came Huss from a landlady, her name was Frauw Künigine, who was a happy landlady, and told him to be willing, because she could see by his clothes that it was a strange guest. "

The histories are concluded with the story of the laying out and the funeral of Eulenspiegel. The beginning and end of life refer to puzzling "coincidences" that have been interpreted in many ways in the aftermath.

Nasreddin Hodja

Nasreddin Hodscha could in the 13./14. Have lived in one of the Turkish-speaking countries in the 19th century. Similar to those of Eulenspiegel, a large number of stories are known that show the hero to be strangely gifted, seemingly illogical and precisely for this reason didactically valuable.

The first of the stories, as published by Gerhard Oberländer, tells how Nasreddin is called by his mother. When he appears after a long wait, he explains to his mother that he was looking for his top in the garden after he lost it in the stable.

"You fool! How can you look for a top in the garden if you've lost it in the stable! "

"Because it's dark in the stable and light in the garden."

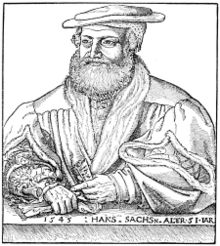

Hans Sachs

Hans Sachs (1494–1576) is considered to be the first poet to independently edit the Eulenspiegel stories in the Volksbuch.

“Years ago, Eulenspiegel, with all its mischief, ran across the field that winter, had bad clothes and no money; while there he saw from afar stubborn stuff riding towards each other. "

The innocent child in the folk book is represented here from the outset as having experienced mischief. In the course of the 16th and 17th centuries, Eulenspiegelei degenerated into a coarse farce.

Christian Fürchtegott Gellert

The Eulenspiegel epic Christian Fürchtegott Gellert (1715–1769) shows the type of Eulenspiegelei who is particularly schoolmasterly oriented: <quote> "The fool who often lacks much less wit than many who like to laugh at him, and who perhaps, to make others wise, the office of the silly chosen ... “Eulenspiegelei is becoming more and more a didactic example. </quote>

Johann Nepomuk Nestroy

Johann Nepomuk Nestroy (1801–1862) worked out the Eulenspiegel figure as a kind of vagabond.

“Eulenspiegel's performance song

Live really happily and be around, / That, I say, that is the greatest art. "

He becomes the deus ex machina when it comes to helping the distressed. The use of Eulenspiegel as a hero of freedom is already becoming apparent, as it should be shaped primarily in the literature of so-called Young Germany.

Julius von Voss

Julius von Voß (1768–1832) lets the figure of Eulenspiegel arrive as a court jester in his story "Eulenspiegel in the 19th century or fool's joke and gimpel wisdom" (1809):

Eulenspiegel is expelled from the country based on the relevant stories in the Volksbuch. Should he approach the prince again, he faces a life chain sentence. Nevertheless, Eulenspiegel approaches the prince in a boat and refers to his relief that he is not on land, but on the prince's water. In the end he was given the office of foolish advisor at court when the prince gave him a chain as a symbol of the chain punishment imposed.

Charles de Coster

Charles de Coster (1827–1879) relocated the setting to Flanders in his novel The legend and the heroic, happy and glorious adventures of Ulenspiegel and Lamme Goedzak and transformed Eulenspiegel into a freedom hero in the struggle of the Dutch against Spanish rule.

“Everything was sugar and honey for them. When the innkeeper had seen the Prince's letters, he gave Ulenspiegel for this fifty Karolus and would not accept any money for the turkey he served them or for the Dobbele-Klauwaert with which he doused them. He also warned him about the blood court spies that were there at Kortfijk, which is why he should curb his tongue and that of his companion. "

Gerhart Hauptmann

Gerhart Hauptmann (1862–1946) placed the figure of Till in the period after the First World War in his epic “The great fighter, country driver, juggler and magician, Till Eulenspiegel, adventure, pranks, jugglery, faces and dreams” (1928). He acts as a visionary in a time of crisis. Hauptmann occasionally referred to his "Eulenspiegel" as his "Faust II". In the 20th century, Eulenspiegelei mutated into a figure of identification for a new political attitude.

Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956) turned his Eulenspiegel into a political agitator. The 5 Eulenspiegel stories were created in 1948 for a planned Eulenspiegel film.

“One, two, three, what's an egg?

Eulenspiegel was the son of a farmer, but for a long time he had nothing to do with the peasants' war against the masters. He diligently pursued his small trade as a showman at fairs and often even drove his hunger away with all sorts of antics in which he tricked the villagers as a real peasant catcher. But one day he encountered a hardship that annoyed him so much that he swore vengeance on the gentlemen and so fell on the farmers' side without much thought or appeal. "

Erich Kaestner

Erich Kästner (1899–1974) introduced the Eulenspiegel material to children's and young people's literature. Eulenspiegel's childhood in the milieu of a traveling circus is portrayed in order to gain a figure of identification for children: hence the art of tight-rope dancing and clowning. In 12 selected stories, the hero is freed from the coarseness of past centuries as a child-like intact figure. Eulenspiegelei is the art of preserving one's childlike originality in times of depraved adults. In the phase of the writing ban by National Socialism, Kästner wanted to reach the children of the Germans in order to convey something of kindness, art and humor to them.

Christa and Gerhard Wolf

Christa and Gerhard Wolf (born 1929 and 1928) relocate the time of Till Eulenspiegel to the early 16th century in their film narration in order to identify the hero as an agitator of new worldviews.

"A fair at the beginning of the 16th century: a trading place for goods, news, rumors, new ideas, a place for contact between the various social classes, a place where the nervousness and unrest of the incited times are concentrated."

In this way, Eulenspiegel mutates completely into the protagonist of a new world politics and social structure.

The classic scenes

baptism

At the beginning of the original Eulenspiegel stories is the magic three number. Hermann Bote tells of the triple baptism: first the pastor of the neighboring village drizzled the boy with water, then the nurse and the child fell into the water, and finally the dirty baby was baptized a third time in a tub, so to speak.

In Christian cultures, baptism is seen as the mystery of the alliance between man and God. Eulenspiegel's baptism is seen as magical. “You have to say it three times”, it will be called later in Goethe's study before Mephistopheles appears. The original Eulenspiegel concept is understood as if an otherworldly power determines Eulenspiegelei. The rogue's entrance and exit (see the section on the entombment and the tombstone) are marked by powers on the other side.

With the development of the coarse farce (cf. Hans Sachs, Fischart, Ayrer), the magic of triple baptism and the mysterious whereabouts of the corpse is suppressed. Only Erich Kästner brings the triple baptism back into the reader's consciousness. Christa and Gerhard Wolf even connect the process with the appearance of the Three Kings, who have been the sign of a reincarnated deity since the birth of Christ.

Lately the motif of the triple baptism has been particularly worked out: the "old", i.e. H. Thousands of times incarnated soul does not simply get involved in all the tests of its highly developed spirituality that lie ahead. She protests against wrong naming.

Tightrope walk

The tightrope walk has been portrayed several times in literary history as a balancing act in life. In this sense, Eulenspiegel's tightrope walk is interpreted as a balancing act between “realities”.

Kästner, who introduced the Eulenspiegel topic to children's literature, currently understands the symbolism of tightrope walking as an attempt to tell children truths and good things in German, while Kästner had forbidden publication under National Socialism.

Abelard (2009) says: “Friends, do you know how to dance on a rope? The adults call it body control. So if someone controls his body, he may be able to balance on a laundry rope from a skylight across the river to the skylight of the town hall. You will say 'tight rope dancing', 'you can go from house to house! You don't need the town hall for that. ' But I, dear friends, I - Till Aulenspeegel - tell you: tightrope walking is always balancing from the parents' home to the public. For example, I practiced tightrope walking. You need good, sturdy shoes. And you need a pillar that stands exactly above the shoes. "

Beehive

The beehive history tells how Eulenspiegel crawls into an empty beehive. Thieves steal the basket because they think there is a lot of honey in the honeycomb. By concealed pulling in the thieves' hair, Eulenspiegel incites the two thieves against each other until they kill each other.

The story by Aulenspeegel in the beehive has occasionally been interpreted psychoanalytically: the already grown-up hero withdraws into his childlike memory. It is a regression : updating of the child's behavior in the adult.

The classic concept of the Latin proverb: “ Divide et impera !” ( Divide and rule!) Is varied in many ways over the course of history.

Spiritual healing

The story of Eulenspiegel's healing of the sick has been understood as a comedy of imaginary illness since the popular book. Eulenspiegel is announced as a qualified doctor and whispers to all the sick that soon he will burn the sickest man to produce a healing powder from his corpse. In this way he succeeds in getting the countless hypochondriacs to flee the hospital.

In addition to allusions to health policy, the portrayal of spiritual healing through Eulenspiegel's method is remarkable.

Journeyman baker

Eulenspiegel's cunning arguments with rich master bakers have been varied numerous times. The Volksbuch tells several versions. Eulenspiegel allegedly orders a sack full of bread on behalf of a rich traveler. The apprentice should come along and receive the money from the client. On the way he drops a loaf of bread in the dirt and sends the apprentice to fetch an unspoilt piece. In the meantime he makes off with his prey.

Probably the most famous story tells how Eulenspiegel baked monkeys. Instead of baking bread according to the master's orders, Eulenspiegel creates many small monkeys and sells them for a profit. It is one of the few histories that is not distorted by gross farces. Recently this story has been portrayed as a typical symptom of a child with an “old” soul.

Guardian

As a tower keeper, Eulenspiegel's job is to keep an eye out for enemies and to signal the approach of any threatening creatures with trumpet signals. In the different versions of the Eulenspiegelstoff these threatening beings are understood as physical enemies or as enemies in a figurative sense.

Churchyard

The Duke of Lüneburg banished Eulenspiegel on the death penalty if he were to return to the Lüneburg countryside. Thereupon Eulenspiegel stands on an upside-down horse - as a sign of his foolishness. In other versions, Eulenspiegel buys a load of graveyard soil and sits down in a cart, so to speak, on God's field.

Schneider's knot

Eulenspiegel called a training course for tailors and told those who had traveled from afar that they should tie a knot at the end of a thread. This profound instruction about the anchoring of the meaning of life is not accepted by the tailors, so that Eulenspiegel - as so often - is chased away.

How Aulenspeegel taught a donkey to read

Animal linguistics researched in the 20th century also finds its forerunner in the Eulenspiegel material. Eulenspiegel teaches a donkey to read by holding a book in front of its nose and waiting for the animal to call "IA". This history has become the paradigm of reading didactics over the centuries .

Furrier

Eulenspiegel sews a living animal into the fur of a hare and sells his work to furriers. This fraud has in many ways been interpreted as teaching the wrongdoing of fur-makers, politicians, or the wealthy in general. In particular, the cruelty to animals by killing fur animals has recently been emphasized.

Eulenspiegel's funeral

The near-death experiences, as explored in the last decades of the 20th century by Kübler-Ross (1970) and Moody (1980), have made the secrets of the corpse and the whereabouts of the soul, known for thousands of years, a little more transparent to let. It is reported that the soul hovers over its deceased body and very precisely perceives the processes that take place around it (so-called panoramic view). After that, there seems to be an encounter with close relatives who have already died and possibly an existence for a few weeks between the living (see the experiences of the apparition ). Only when the soul has found the so-called peace is it ready to go "into the light" (cf. the experiences of Christ's Ascension).

Eulenspiegel's stories about the entombment and removal of the tombstone, about his legacy and the Poltergeist experiences of the bereaved belong in this area. Particularly in the "Historien" of the Braunschweig and Strasbourg Eulenspiegel books there are more detailed information about the mysterious findings of the bereaved in the time shortly after Eulenspiegel's death.

Conclusion

The variability of the Eulenspiegelei is quite diverse over the course of 500 years of literary history. It ranges from flat deception, greed and greed to the glorified bliss of a loving soul who means well but does not please the foolish. In between there are democratic ideals of freedom, altruistic willingness to help, good-natured laughter and social commitment. In the end, you have to realize that there is no such thing as Eulenspiegel, but rather a multiple mixture of very different types of Eulenspiegel personifying characters.

literature

- Siegfried H. Sichtermann (Ed.) Hermann Bote: An entertaining book by Till Eulenspiegel from the country of Braunschweig. Insel, Frankfurt 1978, ISBN 3-458-32036-9 .

- Bertolt Brecht: Collected works in 20 volumes. Vol. 11. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1967.

- Gerd Frank (Ed.): The rogue from the Bosporus. Anecdotes about Nasreddin Hodscha. Edition Orient, Meerbusch 1994, ISBN 3-922825-55-9 .

- Elisabeth Frenzel : Substances of world literature. A lexicon of longitudinal sections of the history of poetry (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 300). 8th, revised and expanded edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-520-30008-7 .

- Jean-Paul Garnier: Nasreddin Hodscha, the Turkish Till Eulenspiegel. Munich 1965. (Pendo, Zurich 1984, ISBN 3-85842-083-2 )

- Christian Fürchtegott Gellert: Complete Fables and Stories. Hahn, Leipzig 1842.

- Erich Kästner: Till Eulenspiegel. Hamburg 1938. (Dressler, Hamburg 1991, ISBN 3-7915-3530-7 )

- H. Neumann-Wirsing, HJ Kersting (Ed.): Systemic Supervision. Or Till Eulenspiegel's fools. Kersting, Aachen 1993, ISBN 3-928047-05-1 .

- Karl Pannier (Ed.): Hans Sachs. Selected poetic works. Leipzig 1879.

- Siegfried H. Sichtermann (Ed.): The changes of Till Eulenspiegel. Böhlau, Cologne 1982, ISBN 3-412-02981-5 .

- Christa Wolf, Gerhard Wolf: Till Eulenspiegel. Luchterhand, Frankfurt a. M. 1990, ISBN 3-630-61430-2 .

- Wolfgang Abelard: Till Aulenspeegel. A book for young people for old souls. Images by Georgia Röder. Gelnhausen 2012.

Individual evidence

- ↑ cf. Frank 1994

- ↑ cf. Frenzel 1992, p. 209

- ↑ Uluarum speculum 1558

- ↑ cf. Frenzel 1992, p. 210 f.

- ↑ Sichtermann (1978)

- ↑ cf. Sifter (1982)

- ↑ cf. Oberländer 1984, p. 10.

- ↑ cf. Pannier1879

- ↑ cf. Gellert 1852

- ↑ cf. his folk play The Evil Spirit Lumpazivagabundus

- ↑ cf. Sichtermann (1982, p. 47 ff.)

- ↑ cf. Sichtermann 1982, p. 39 ff.

- ↑ cf. Sichtermann (1982, p. 88 ff.)

- ↑ cf. Sichtermann (1982, p. 182)

- ↑ cf. Brecht 1967

- ↑ cf. Brecht 1967, vol. 11 p 379

- ↑ Goethe, JW: Urfaust, cf. Schmidt, Erich: Goethe's Faust in its original form based on Göchhausen's handwriting. Weimar: Hermann Böhlau. 1882

- ↑ cf. Wolf 1973

- ↑ cf. Abelard 2009, chap. 2

- ↑ Messenger (1978)

- ↑ cf. Georg Heym : The tightrope walkers. In: The colorful book , 1914 or: Michael Ende : Ballad from the tightrope walker Felix Twigleg. Kindermann 2011 or: Waltraud Treber: tightrope walker. A life between realities. Geest-Verlag o. J. or Michael Göring : The tightrope walker. Novel 2011

- ↑ Messenger 1978

- ↑ cf. Neumann savoy cabbage 1993

- ↑ cf. Abelard 2012

- ↑ Messenger 1978

- ↑ Abelard 2012

- ↑ cf. Messenger 1978

- ↑ cf. Bote 1978, Kästner 1938, Abelard 2012

- ↑ Messenger 1978

- ↑ Kästner 1938, Abelard 2012

- ↑ Messenger 1978

- ↑ Bote 1978, Kästner 1938, Abelard 2012

- ↑ Messenger 1978

- ↑ Messenger 1978

- ↑ cf. Abelard 2012