Finger animal

| Finger animal | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Finger animal ( Daubentonia madagascariensis ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the partial order | ||||||||||||

| Chiromyiformes | ||||||||||||

| Anthony & Coupin , 1931 | ||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the family | ||||||||||||

| Daubentoniidae | ||||||||||||

| JE Gray , 1863 | ||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the genus | ||||||||||||

| Daubentonia | ||||||||||||

| Geoffroy , 1795 | ||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the species | ||||||||||||

| Daubentonia madagascariensis | ||||||||||||

| ( Gmelin , 1788) |

The finger animal or aye-aye ( Daubentonia madagascariensis ) is a primate species from the group of lemurs . It is a nocturnal omnivore living in Madagascar , which is characterized by its teeth, which are unique among primates, and the modified fingers that give it its name. It is the only living member of the Daubentoniidae family, a second recent species, the giant finger animal ( Daubentonia robusta ), has become extinct.

features

Finger animals are large, relatively slender animals. They are the largest nocturnal primates. They reach a head body length of 36 to 44 centimeters, the tail is an additional 50 to 60 centimeters long. The weight is around 2 to 3 kilograms. A sexual dimorphism is only weak, with an average of 2.7 kilograms, the males are slightly heavier than the females, who reach an average of 2.5 kilograms. The fur of these animals is rough, shaggy and long, it is usually dark brown to black in color. Especially on the back, the outer hairs often end in white tips; the face and stomach are light gray, the hands and feet are colored black.

The tail is longer than the body and extremely bushy, the hair there can be up to 10 centimeters long. The limbs are thin, the hands and feet are relatively large. With the exception of the big toe, which has a nail , all fingers and toes end in claws - a very rare feature among primates that is only found in the (not closely related) marmosets . The thumb is flexible, but not opposable , but the big toe, as in all primates with the exception of humans , can be opposed to the other toes. The third and fourth fingers are significantly longer, and the third finger is also noticeably thin. Like the giant panda , the finger animal has a mobile appendage consisting of bone and cartilage on the wrist of the front paws, which serves as a “pseudo-thumb” and possibly strengthens the grip of the over-specialized hand when climbing. What is unique among primates is that the female teat pair is located in the groin region (inguinal).

The head is round and relatively massive. The large eyes are sand-colored; they are directed forward and surrounded by a dark eye ring. As with all wet-nosed monkeys, there is a tapetum lucidum , a reflective layer , in the eye . Finger animals are one of the few primates that have a nictitating membrane (“third eyelid”) - this probably serves to protect the eye when the animals gnaw through wood. The ears are hairless, large and rounded. Finger animals have the largest brain of all wet-nosed monkeys relative to body size.

The dentition is unique among primates and shows convergences to the teeth of rodents . The incisors are large and curved, only the front side is covered with tooth enamel , which makes them chisel-like. The incisors have open tooth roots and grow throughout their life. The canines are missing, and there is a large gap between the incisors and the molars , known as the diastema . A premolar is only present in the upper jaw ; these teeth are also absent in the lower jaw. They have three molars per half of the jaw , these are flattened and have inconspicuous cusps. The following tooth formula results : I 1 / 1- C 0 / 0- P 1 / 0- M 3/3. With 18 teeth, they have the fewest of all primates, and they are the only wet-nosed monkeys without a tooth comb (the front-facing incisors and canines of the lower jaw). In primary teeth , two incisors and premolars and an upper canine are available.

distribution and habitat

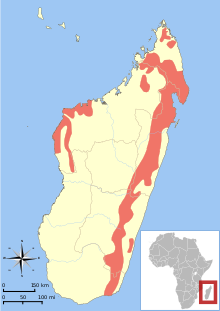

Their habitat is forests, they can cope with different types of forest. In addition to rainforests and deciduous forests, they are also native to swamp and mangrove forests and sometimes even in plantations.

Finger animals are endemic to the island of Madagascar and have one of the largest ranges of all primates on this island. On the one hand, they inhabit the tropical rainforests along the east coast, but, contrary to earlier assumptions, they also live in the drier deciduous forests in the northwest and west. In contrast, they are absent in the settlement area of the subfossil giant finger animal ( Daubentonia robusta ) in the dry south-western part and in the unforested central highlands. As part of conservation measures, they were relocated to areas where they were not originally native, such as the island of Nosy Mangabe .

Way of life

Activity times and movement

Finger animals are nocturnal tree dwellers; during the day they sleep in self-made nests in the thick foliage. They are usually 10 to 15 meters high and have a diameter of around 50 centimeters. They are egg-shaped structures made of leaves and twigs that are closed at the top and have a side entrance. Making a nest takes around 24 hours. Every finger animal has several nests in its territory . There is an observation of an animal that used seven different nests in four weeks. Due to the overlapping territories, the nests can be close to each other, and sometimes there are even several in the same tree. Different individuals can use the same nest at different times; in one observation, four finger animals used the same nest. It also happens that abandoned nests are moved into and repaired by other individuals.

The first finger animals can leave their nests 30 minutes before sunset - males a little earlier than females - and they only return to their roosts at sunrise. They spend more than 80% of their time moving around and looking for food, other activities include grooming and resting. Several times a night they search their fur for up to 30 minutes with their extended fingers for parasites. In the rest phases the animals sit down, but remain alert and do not fall asleep. These rest periods can last up to two hours.

Aware animals use several methods of locomotion, including four-legged walking and jumping. Thanks to their claws and their strong big toe, they can also climb down trees upside down. Sometimes they hang upside down on a branch and only hold on with their hind legs. In order not to damage the long, thin fingers, they are often curled up when moving. They often come to the ground and can cover greater distances there. When doing this, step on with the heels of your hands, your fingers not touching the ground.

Social and territorial behavior

Finger animals live largely solitary outside of the mating season, but there are still interactions. So you can sometimes see up to four animals searching for food together or moving around. These interactions occur between multiple males or between males and females, but never between two or more females. In general, males interact more frequently with other males than with females, but sometimes there are arguments when two males meet. The motives and backgrounds of this behavior are not yet known.

Males have very large territories of 125 to 215 hectares that overlap considerably with those of other males and females. The territories of the females are significantly smaller with 30 to 40 hectares and do not overlap, females always encounter other females aggressively. The areas are marked with urine and glandular secretions or possibly with bites in the tree bark. The length of the daily forays is 1.2 to 2.3 kilometers and is larger in males than females.

Finger animals communicate with one another using a series of sounds. To establish contact with other animals, a "iiip" sound is emitted, and young animals call for their mother with a "kriii" sound, which usually expresses discomfort. Animals that are close together emit a “gggnoff”, which often results in the common foraging or grooming. An "aaack" sounds in hostile encounters, a "ron-tsit" serves as a warning. During the escape, they utter a two-syllable “hai-hai”, from which the name Aye-Aye is presumably derived.

nutrition

Finger animals are omnivores , the main components of their food are insects and their larvae, fruits , nuts , nectar and mushrooms . For insect larvae, they have specialized in longhorn beetles and have developed their own hunting technique. The wood is tapped rhythmically with the extended third finger; Thanks to their excellent hearing, they can locate their prey using the cavities. They gnaw holes in the bark with their incisors, then insert their thin fingers to fish for larvae. This form of foraging is similar to that of the woodpeckers that are missing in Madagascar .

The nectar of the travelers' tree ( Ravenala madagascariensis ), the fruits of the ramy tree ( Canarium madagascariensis ) and outgrowths on the bark of the merbau tree Intsia bijuga are important plant components of the diet . Coconuts are also a preferred food source wherever they are cultivated . Finger animals prefer unripe fruit, so they tap them with their third finger, probably to find out how much milk and pulp they contain. Then they gnaw open the shell, it takes about two minutes to create a hole 3 to 4 centimeters in diameter. With quick movements of the third finger you first convey the coconut milk and then the pulp into your mouth. In a similar way - first gnawing with their sharp incisors, then quickly fishing out with their long fingers - they also eat mangoes , avocados and even bird eggs. They also use the long third finger when drinking: with quick back and forth movements (more than three times per second) they convey the liquid into their mouth.

In general, large differences can be observed in the diet of the finger animals; the composition of the food can vary greatly depending on the season and habitat.

Reproduction and development

Unlike many other lemurs, fingertips do not have a set mating season. The female's oestrus only sets in once a year for three to nine days, then it begins to quickly cross its territory and attract the males with special calls. Up to six males then gather and fight with each other for mating privilege. The copulation lasts about an hour, after which the female moves to another place and starts her advertising calls again. The mating behavior of the finger animals is polyandric , that is, a female reproduces with several males.

After a gestation period of around 160 to 170 days, the female gives birth to a single young. Newborns weigh 90 to 140 grams; they are similar to adult animals, but their fur is significantly lighter on the face, shoulders and stomach. The eyes are also green at first and the ears hang down. In the first two months of life they always stay close to their mother, although she sometimes “parks” her in the nest while she is looking for food. Animals in human care often carry the young in their mouths.

The young animals eat solid food for the first time at the age of three months, and at the same age they also start with playful movements. They are finally weaned at around six to seven months. They are allowed to leave their mother when they are around one and a half to two years old. Sexual maturity occurs at 2.5 to 3.5 years of age. The reproductive rate of the finger animals is low; the female gives birth to a young animal only every two to three years.

Threats and Life Expectancy

Little is known about the natural enemies of the finger animals, the only known predator is the fossa . How old the animals get in the wild has not been researched; in human care they can reach an age of 24 years.

Finger animals and humans

Finger animals in culture

The inhabitants of Madagascar have different views of the finger animal depending on the region and culture. Sometimes it is viewed as a good omen, sometimes as an evil spirit and is killed if possible at an encounter. They are often ascribed magical abilities. There are a number of legends, especially around the "good finger animals". So there is the story that the finger animals make a pillow out of grass for every person who sleeps in the forest. Should someone find this under his head, he will soon have great wealth, but whoever finds the pillow under his feet will soon fall victim to the magical powers of a wizard. Some Malagasy people believe that anyone who kills a finger animal will die within a year. That's why they quickly release animals that have accidentally fallen into traps.

In Europe, the species is kept in several British zoos and Frankfurt. The breeding of the animals is considered very difficult despite isolated successes. A few years ago the species was considered unbredable.

Threat and protection

The range of the finger animals is larger and the threat less than assumed until recently. Nevertheless, the animals are exposed to some threats. Since they often invade plantations and eat the crops, they are considered a plague and are persecuted. Trees growing in the wild that provide food for them are felled to process the wood. In some regions of Madagascar, they are also hunted for their meat. The IUCN lists this type due to the decline of populations by 50% in the last 24 years (three generations) as "high risk" ( endangered one).

Finger animals are found in numerous nature parks and nature reserves in Madagascar. There are also breeding programs for the conservation of the species in several zoos and institutions. The Duke Lemur Center in Durham (North Carolina) and the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust on the Channel Island of Jersey are in charge of this . The Grandidier Fund with the attached Tsimbazaza Botanical and Zoological Park has also taken on the animals.

Systematics

Scientific names of the finger animal:

- Sciurus madagascariensis ( Johann Friedrich Gmelin 1788)

- Lemur psilodactylu ( George Shaw 1800)

- Cheiromys madascariensis var.laniger ( Guillaume Grandidier 1929)

The finger animal is classified within the primates to the subordination of the wet-nosed monkey (Strepsirrhini), and in its own suborder Chiromyiformes. Within this group, however, it has a special position and forms the sister taxon of the lemurs . It is the only living member of the finger animal family (Daubentoniidae) and the genus Daubentonia .

Subfossil is another species, namely the giant finger animal ( Daubentonia robusta ). Remains of these animals have been found in southwest Madagascar. They were a third larger than today's finger animals and became extinct about a thousand years ago.

When it was first described in 1788, the finger animal was classified as a rodent due to its incisors . The original name Sciurus madagascariensis saw the animal as a representative of the squirrel (Sciuridae). In 1795 a separate genus, Daubentonia , was created for the animal, named after Louis Jean-Marie Daubenton , but its systematic position has long been a mystery. It was not until the middle of the 19th century that the English zoologist Richard Owen found similarities between the deciduous teeth of the acoustics and other primates and thus underpinned the affiliation to this order.

swell

literature

- Nick Garbutt: Mammals of Madagascar. A Complete Guide. Yale University Press, New Haven CT 2007, ISBN 978-0-300-12550-4 .

- Gerald Durrell : The Aye-Aye And I. A Rescue Expedition in Madagascar . Harper Collins, London 1992, ISBN 1-55970-204-4 .

- Thomas Geissmann : Comparative Primatology. Springer-Verlag, Berlin et al. 2002, ISBN 3-540-43645-6 .

- Peter Kappeler: finger animal. In: David MacDonald (ed.): The great encyclopedia of mammals. Könemann Verlag, Königswinter 2004, ISBN 3-8331-1006-6 , pp. 322–323, German translation of the original edition from 2001.

- Ronald M. Nowak: Walker's Mammals of the World. 6th edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore MD 1999, ISBN 0-8018-5789-9 .

Web links

- KJ Gron: Primate Factsheets: Aye-aye ( Daubentonia madagascariensis )

- Information on Animal Diversity Web

- Information at theprimata.com

- Daubentonia madagascariensis onthe IUCN Red List of Threatened Species . Retrieved February 28, 2009.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Adam Hartstone-Rose et al. A primate with a panda's thumb: the anatomy of the pseudothumb of Daubentonia madagascariensis. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, October, 2019; doi: 10.1002 / ajpa.23936

- ↑ [1] ZTL 16.6

- ↑ Ministere de l'enseignement superieur: Missions du parc botanique et zoologique de tsimbazaza

- ↑ Don E. Wilson, DeeAnn M. Reeder (Ed.): Mammal Species of the World. A taxonomic and geographic Reference. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore MD 2005, ISBN 0-8018-8221-4 .