Exchange rate system

The exchange rate system (also known as the exchange rate regime ) is the way in which an exchange rate , i.e. the exchange ratio between two currencies , is formed. Two basic forms can be distinguished: If an exchange rate is formed freely by the supply and demand behavior on the foreign exchange market , there is a flexible exchange rate.

A system of fixed exchange rates, on the other hand, is created through state agreements and must be secured through interventions. There are also numerous intermediate and special forms. The choice of a country's exchange rate system is influenced by political goals and existing international ties. The exchange rate system is part of a country's monetary system .

Flexible exchange rates

properties

Flexible (free) exchange rates ( "floating" ) correspond to the principle of free market pricing on the foreign exchange market . The course formation takes place exclusively through the meeting of supply and demand, i. H. basically without government intervention. The market mechanism on the foreign exchange market, the so-called exchange rate mechanism , ensures in theory that the supply and demand quantities match at the equilibrium rate (foreign exchange market equilibrium).

In order for an equilibrium to arise on the foreign exchange market, the condition of interest parity must be met. This hypothesis states that the effective return on domestic and foreign investments must be the same. It implies that interest rate differences between domestic and foreign investments are based solely on expected changes in exchange rates. I.e. at the equilibrium rate, the expected short-term returns are equal.

If the supply and / or demand for foreign exchange of the various currencies shift over time, this leads to a change in the equilibrium exchange rates. These fluctuations are called "floating". If the exchange rate is influenced by the central banks in order to smooth out short-term fluctuations and to ensure orderly market conditions, it is called " managed floating ". If the interventions aim to manipulate the exchange rate trend, this is referred to as "dirty floating".

So that an adjustment of the currency market equilibrium can take place after disruptions, for example due to increasing imports , the conditions of complete competition must be met. The foreign exchange market comes very close to this ideal model, as many suppliers and buyers are regularly active in the market, the market transparency is very high and the factual, personal or spatial differentiations are hardly significant.

Foreign exchange supply and demand originate on the one hand from foreign traders who carry out export and import transactions in foreign or domestic currencies. Second, they result from interest rate arbitrageurs that their financial transactions of interest rate differentials make and exchange rate expectations dependent.

A system of flexible exchange rates does not set a central rate specified by monetary policy agreements .

Examples of countries with completely flexible exchange rates are the USA , the United Kingdom , Norway and Sweden .

Advantages and disadvantages

The main advantage of a flexible exchange rate system is that the country maintains its own monetary policy . So there are better ways to respond to shocks . By eliminating the obligation to intervene, the central banks can gain full control over the development of the domestic money supply . Since an adjustment of the exchange rate is still possible if the national inflation rate , productivity or economic development deviates from the development abroad , flexible exchange rates support the constant adjustment of the economy .

By devaluing a currency, the exports of the country concerned are made easier because they are cheaper for foreign countries. As a result, the economic power of this country is boosted again, while the foreign countries are increasingly asking for its currency again in order to be able to buy its exports. This increases the currency value of the affected country again, making its exports more difficult, but making imports easier. The mechanism of free exchange rates thus has a balancing effect on the unbalanced balance of payments between countries ( exchange rate mechanism ).

On the other hand, free exchange rates are subject to strong fluctuations over time. This high volatility can sometimes be difficult to control by monetary policy. The main disadvantages of a system of flexible exchange rates are instability and the associated uncertainty and unpredictability.

Fixed exchange rates

properties

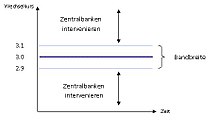

In systems of fixed (fixed) exchange rates, the participating countries agree on a fixed central rate, the so-called parity , and try to keep this constant through interventions. The exchange rate can be linked by the central bank to another currency or to a currency basket . However, the exchange rates of countries with a system of fixed exchange rates are not fundamentally immutable. When speaking of fixed exchange rates, bandwidth systems are usually meant in which the exchange rates can deviate from the central parities within certain bandwidths (e.g. ± 1%).

However, if the exchange rate threatens to break out of the range, the central banks involved must intervene in the context of foreign exchange market interventions and act as suppliers or buyers themselves. The corresponding highs and lows at the end of the range are called the upper and lower intervention points. Changes in exchange rates beyond the bandwidths can only be brought about by changes in parity, so-called realignments .

Even in the system of fixed exchange rates, the exchange rate and nominal interest rate must meet the condition of interest parity . If investors expect the exchange rate to remain unchanged in the future, they are demanding the same interest rate in both countries involved. I.e. With fixed exchange rates and perfect capital mobility, the domestic interest rate must correspond to the foreign one.

Examples of fixed rate systems are the gold standard , the Bretton Woods system and the European monetary system . Monetary union is an extreme case of fixed exchange rate pegs .

Advantages and disadvantages

The advantages of a fixed exchange rate system are exchange rate stability and the consequent secure calculability and predictability of exchange rates. The low transaction costs are also positive . Since the central bank directs its policy exclusively to maintaining an exchange rate relationship, the credibility of this exchange rate system is increased.

The decisive disadvantage of fixed exchange rates is the lack of an autonomous monetary policy in the country. In doing so, the central bank is giving up a very powerful tool for correcting trade imbalances and influencing the economy . The fiscal policy alone is not enough. It should be noted that devaluation expectations can actually lead to devaluations . The exchange rates in a fixed rate system are ultimately always politically influenced and thus distorted by the foreign exchange market interventions of the central banks. However, holding on to inappropriate parities for too long makes the exchange rate regime susceptible to speculation . Another problem with fixed exchange rates is the restriction of the freedom of action of economic policy . This can manifest itself in the form of imported inflation or international illiquidity of the country.

Classification of exchange rate systems

In practice, within the spectrum defined by fixed and flexible exchange rates, there are a number of further exchange rate arrangements in graduated form:

- Exchange rate regulation without their own legal tender: several countries agree to use the same legal tender ( monetary union ) or one country chooses the currency of another country as the sole legal tender (so-called dollarization )

- Exchange rate regulation in the form of a currency board (monetary office): a country undertakes to exchange the domestic currency at a fixed exchange rate for a certain foreign currency, whereby the limitation of the monetary policy is determined by law or constitution and thus a change in the exchange rate is excluded

- Fixed exchange rates pegged to a single currency or a currency basket: the currency is formally or de facto pegged with a fixed parity to a major currency or a currency basket ; the exchange rate can fluctuate within a range (for example 1%) around the central rate

- Gradual rate adjustments or bandwidth adjustments

- Crawling peg : the exchange rate is regularly adjusted in small steps with a fixed percentage previously announced by the central bank

- Adjustable Peg: the exchange rate is kept within a certain range that can be shifted up or down with the parity

- Controlled floating ( managed floating ): relatively flexible exchange rates, at which the monetary authority reserves the right to influence the exchange rate development through voluntary interventions in the foreign exchange market

- Independent floating (freely flexible exchange rates): the formation of exchange rates is generally left to market forces, foreign exchange market interventions are made at most to smooth out short-term fluctuations or to avoid excessive exchange rate fluctuations

Historical development

In the 19th century, foreign trade (trade across one or more national borders) increased sharply for numerous reasons (see also globalization ):

- significant population growth in most of the world's countries

- Industrialization (first in Great Britain, then in many other countries)

- Construction of the railway network

- The advent of steam shipping

- Construction of numerous navigable canals; Improving the navigability of rivers

- Colonization of numerous overseas countries (see Age of Imperialism , Race for Africa )

- the telegraph and later the telephone facilitated communication and trade

- more international division of labor

- fewer small states (e.g. Italy from 1861, German Empire from 1871)

Between 1880 and 1914, the exchange rate system was the classic gold standard , which prevailed over bimetallism (gold-silver currency) or the silver standard . The price of a country's own currency was fixed in units of gold, and there was an obligation to exchange gold for its own currency at this rate at any time. The exchange rates of the gold standard countries remained constant during this phase. Practically all economically important countries belonged to the gold standard.

After the gold standard was suspended during the First World War , attempts were made to restore the gold standard in a modified form in the period between the two world wars. After a period of flexible exchange rates, most countries returned to fixed gold parities. The gold currency standard was now practiced: in accordance with the recommendations of the International Economic Conference in Genoa (1922), currency was held alongside gold as currency reserves .

The uncoordinated return to gold parities with the result of over- and undervaluation of important currencies led to the collapse of the restored gold standard as an international monetary system. The trigger was the suspension of the Bank of England's obligation to redeem gold for the British pound on September 21, 1931. In the following period, there were devaluations of other currencies and monetary policy disintegration prevailed. This phase was characterized by the formation of currency blocks:

- Some countries stabilized their exchange rates against the pound sterling , creating a sterling bloc (e.g. members of the British Commonwealth , Portugal and the Scandinavian countries ).

- the countries of the gold bloc, on the other hand, retained the gold parity of their currencies after the devaluation began (e.g. France , Switzerland , the Netherlands ).

The foundations for a new international exchange rate system began as early as during the Second World War . At the international monetary and financial conference of the United Nations on July 22, 1944, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was founded and the Bretton Woods system was adopted as the exchange rate system . It is a system of fixed exchange rates in which the exchange rates were allowed to deviate from parity within a range of 1%. The key currency (the so-called anchor currency ) was the US dollar , which was deposited with gold as a reserve currency.

After a devaluation of the US dollar in 1971 and the subsequent lifting of the obligation to redeem gold for this currency, the fixed rate system of Bretton Woods collapsed in March 1973. As a result, the most important world trading countries switched to more or less flexible exchange rate systems. Years of stagnation and relatively high inflation (collectively called stagflation ) followed in many industrialized countries, aided by two oil crises . In 1978, the members of the IMF were given the choice of the exchange rate system by law.

In March 1979 the European monetary system came into force, which regulated the exchange rates within the European Union until 1998 in the form of a bandwidth system. Most of the participating countries introduced a common currency in January 1999, the euro . From January 1, 1999, the euro was the book currency ; in January 2002 it was introduced as cash.

In recent years the trend in exchange rate systems has moved away from intermediate solutions towards the two extremes:

- Regime with completely flexible exchange rates ( float ) or

- Currency integration, i.e. the most extreme form of fixed exchange rates (hard peg).

Between 1990 and 2004, the number of countries that switched to a completely flexible or extremely rigid exchange rate regime rose sharply. The share among the IMF member countries has risen from around a third to a little more than half. The main reason for this is or was that the two extreme forms were viewed as more crisis-resistant than the intermediate forms.

Choice of exchange rate system

The choice of exchange rate system is fundamentally determined by national interests and international interdependencies. For example, a country that has close trade relations with neighboring countries, is heavily dependent on exports and in which the export sector has a great deal of political influence will prefer a system of fixed exchange rates.

Various efficiency criteria are weighed up , such as:

- Foreign trade dependence

- Width of the export range

- International liquidity

- Priority for internal or external stability as well

- Adaptability of labor markets .

With the decision in favor of a certain exchange rate system, the central banks try implicitly or explicitly to realize exchange rate targets. It should be noted that the three goals

- Exchange rate stability

- Free movement of capital (or currency convertibility) and

- Monetary Policy Autonomy

cannot be achieved simultaneously and completely. This conflict of goals is known as the "impossible trinity" or the impossibility triangle. If the exchange rates are to be kept stable (system of fixed exchange rates), either an independent monetary policy or the free movement of capital must be dispensed with. On the other hand, if a country prefers the free movement of capital and an autonomous monetary policy, this is at the expense of exchange rate stability and means a decision in favor of flexible exchange rates.

Overall, there is agreement among economists that a system of flexible exchange rates is generally preferable to a fixed rate system. There are two exceptions to this principle:

- For a group of strongly integrated countries, a common currency can be the right path, i.e. a monetary union like the European Monetary System.

- Extremely fixed exchange rates such as a currency board or dollarization can be a solution when the central bank is unable to conduct responsible monetary policy under flexible exchange rates.

Overview

The most important regime types, sorted from fixed to flexible.

| Regime type | particularities | example | Specific advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monetary union | At least two countries create a common, possibly new currency | Euro , GDR and Federal Republic of Germany | |

| Foreign currency | Adoption of a foreign currency, "unilateral currency union", "dollarization", "euroization" | Ecuador since 2000 | |

| Currency board | institutionalized coupling with fixed coverage | Argentina from 1991 to 2002, Hong Kong since 1983 | creates great trust through institutionalization |

| fixed exchange rate to anchor currency | Fixed rate to another currency that the central bank intervenes to secure | useful if you are dependent on a large trading partner | |

| fixed exchange rate to currency basket | Fixed rate to a basket of currencies that the central bank safeguards through interventions | useful if you are dependent on several large trading partners | |

| Bandwidth | Fixed course with fluctuation range | Bretton Woods , EWS | Interim solution when changing between flexible and fixed |

| Crawling peg | Fixed rate, regular and announced devaluation / upgrading | Poland from 1991 to 2000 | Confidence through predictability, real overvaluation through inflation can be avoided. |

| Adjustable peg | Fixed rate, irregular and announced devaluation / revaluation | ||

| Managed floating | officially free course, but regularly unannounced interventions | ||

| Dirty floating | officially free course, but rare, unannounced interventions to (roughly) achieve a target course | numerous Southeast Asian countries, Iran, $ - € exchange rate | no official course has to be defended, therefore less susceptible to shocks and speculation |

| flexible course | determined only by private supply and demand | Exchange rate between DKK and ARS (irrelevant for both central banks) |

Individual evidence

- ^ Rolf Caspers: Balance of payments and exchange rates . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-25924-5 , p. 135.

- ^ Rolf Caspers: Balance of payments and exchange rates . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-25924-5 , p. 134.

- ↑ Oliver Blanchard, Gerhard Illing: Macroeconomics . Pearson Studium, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8273-7209-7 , p. 845.

- ^ Rolf Caspers: Balance of payments and exchange rates . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-25924-5 , pp. 141/182.

- ^ W. Albers: Concise Dictionary of Economics (HdWW) . Volume 8, Gustav Fischer, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-525-10257-7 , p. 578.

- ^ Rolf Caspers: Balance of payments and exchange rates . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-25924-5 , p. 135.

- ↑ bancanationale.ch ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF file)

- ↑ Oliver Blanchard, Gerhard Illing: Macroeconomics . Pearson Studium, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8273-7209-7 , p. 621.

- ^ Rolf Caspers: Balance of payments and exchange rates . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-25924-5 , p. 155.

- ↑ bancanationale.ch ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF file).

- ↑ Oliver Blanchard, Gerhard Illing: Macroeconomics . Pearson Studium, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8273-7209-7 , pp. 620–621.

- ^ Rolf Caspers: Balance of payments and exchange rates . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-25924-5 , p. 155.

- ↑ Oliver Blanchard, Gerhard Illing: Macroeconomics . Pearson Studium, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8273-7209-7 , p. 591.

- ^ Rolf Caspers: Balance of payments and exchange rates . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-25924-5 , p. 142.

- ↑ bundesbank.de ( Memento from February 10, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Oliver Blanchard, Gerhard Illing: Macroeconomics . Pearson Studium, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8273-7209-7 , p. 592.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Jarchow: Theory and Politics of Money. 11th edition. Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-8252-2453-8 , p. 446 ff.

- ^ Rolf Caspers: Balance of payments and exchange rates . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-25924-5 , p. 154.

- ↑ bancanationale.ch ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF).

- ↑ Oliver Blanchard, Gerhard Illing: Macroeconomics . Pearson Studium, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8273-7209-7 , pp. 592–621.

- ^ Rolf Caspers: Balance of payments and exchange rates . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-25924-5 , pp. 154-155.

- ↑ a b c Hand-out ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. mcl.fh-osnabrueck.de MS Word .

- ^ Rolf Caspers: Balance of payments and exchange rates . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-25924-5 , pp. 142-143.

- ↑ imf.org

- ↑ H.-J. Jarchow, P. Rühmann: Monetary Foreign Trade II International Monetary Policy. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2002, ISBN 3-8252-1335-8 , pp. 15-163.

- ↑ Oliver Blanchard, Gerhard Illing: Macroeconomics . Pearson Studium, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8273-7209-7 , pp. 591-592.

- ↑ bancanationale.ch ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF file)

- ↑ weltpolitik.net

- ^ Rolf Caspers: Balance of payments and exchange rates . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-25924-5 , pp. 150-158.

- ↑ Oliver Blanchard, Gerhard Illing: Macroeconomics . Pearson Studium, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8273-7209-7 , p. 621.

literature

(Newest first)

- O. Blanchard, G. Illing: Macroeconomics . Pearson Studium, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8273-7209-7 .

- R. Caspers: Balance of payments and exchange rates . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-25924-5 .

- Hans-Joachim Jarchow , P. Rühmann: Monetary Foreign Trade II International Monetary Policy. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2002, ISBN 3-8252-1335-8 .

- Hans-Werner Sinn (Ed.), Ernst Baltensperger : Exchange-Rate Regimes and Currency Unions . Palgrave Macmillan, 1992, ISBN 0-333-56943-1 .

- W. Albers: Concise Dictionary of Economics (HdWW) . Volume 8. Gustav Fischer, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-525-10257-7 .