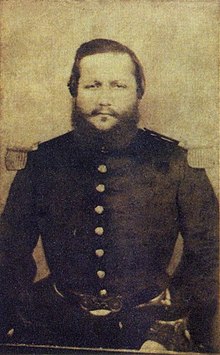

Francisco Solano López

Francisco Solano López Carrillo (born July 24, 1827 near Asunción , Paraguay ; † March 1, 1870 in the Battle of Cerro Corá , Paraguay) was the President of Paraguay from 1862 until his death in 1870. He was the eldest son of President Carlos Antonio López and was his successor. He led and lost Paraguay's Triple Alliance War against Brazil , Argentina and Uruguay .

youth

Francisco López was intended as his future successor by his dictatorial father and was prepared for this role at an early stage. He was fluent in Spanish and Guaraní, and was proficient in English, French and Portuguese. Despite his young age, he was appointed general in 1846 at the age of nineteen and entrusted with the supreme command of the Paraguayan armed forces , which were to support an uprising against the Argentine government in the Argentine province of Corrientes . However, the uprising collapsed before it happened, and he returned with nothing done. The military expedition, which ultimately had no consequences, reinforced López in his feeling that he had military experience.

In June 1853 he was sent to Europe by his father. He was supposed to recruit scientists, technicians and settlers for Paraguay as well as buy ships and modern armaments. The trip took him to England, France, Spain and the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont . In Paris he met the Irish courtesan Eliza Lynch , who became his partner and mother of his children. He took her home with him, where she later became very influential, although he did not marry her.

Seizure of power

In January 1855, López returned to Paraguay. He has now been appointed Vice President and Minister of War in his father's cabinet. After his death he immediately took power in September 1862. This step was subsequently legitimized by Congress. His brother Venancio succeeded him as Minister of War. The president's power was absolute and an intense cult of leadership was built.

Outbreak of war

In Uruguay there had long been a conflict between the parties of the Colorados and the Blancos , which was at times fought as a civil war with great brutality. In April 1863, the leader of the Colorados, Venancio Flores , started an uprising against the Blancos-controlled government. He was supported by Argentina and Brazil. As a result, the Uruguayan government got into great distress and turned to Paraguay for help. López sided with Los Blancos. When Brazil openly intervened militarily in Uruguay, he called for an end to Brazilian interference. Since Brazil reacted negatively, he confiscated a Brazilian ship on the Paraguay River , imprisoned the crew and the governor on board of the Mato Grosso province and declared war on Brazil.

Course of war

In December 1864, López sent an army to Mato Grosso. The Brazilians withdrew there, they concentrated their forces on the much more important theater of war, Uruguay. There they were successful; on February 20, 1865 they were able to conquer the capital Montevideo and use Flores as president. With that the war in Uruguay was already lost for the side supported by Paraguay.

In order to be able to confront the Brazilian troops in Uruguay, López demanded the right to march through the Argentine province of Corrientes from the Argentine President Bartolomé Miter . Argentina, which was officially neutral in the war, but actually allowed ships of the Brazilian Armada to pass through Argentine territory, declined. Subsequently, on March 18, 1865, Paraguay declared war on Argentina. López was appointed marshal by his congress. The Paraguayan troops quickly advanced into Corrientes, meeting little resistance, and took the city of Corrientes . On May 1, 1865, Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay allied themselves in the Triple Alliance treaty for the purpose of joint warfare against Paraguay. They committed themselves in the treaty to continue the war until the fall of López.

The Paraguayans could not hold their conquests in Brazil and Argentina and were pushed back into their own national territory. There they offered desperate resistance. After heavy defeats their situation became hopeless. In August 1867, the dictator considered resigning and going into exile. As the situation became increasingly hopeless, López mistrusted his officers and senior officials and suspected conspiracies everywhere. He had numerous officers executed, partly because he blamed them for military setbacks, and partly because he suspected them of lack of loyalty. A large part of the civil ruling class was sentenced to death, including the two brothers and two sisters of López and his mother and brother-in-law Vicente Barrios . The death sentence against Barrios and one of the brothers was carried out, the rest of the family remained in custody until the end of the war. In addition to numerous high officials, cabinet members, judges, bishops and priests as well as more than 200 foreigners, including several diplomats, were executed on the orders of López or after judgments by his special courts.

After the loss of the capital Asunción, which was captured by Allied troops on January 5, 1869, López continued the resistance. In the final stages, his armed forces consisted largely of poorly armed war invalids, children, and old men. After all, the exhausted and starved remains of the Paraguayan army were hardly fit for action. While trying to cross the Aquidabán River, López was caught by Brazilian soldiers and asked to surrender. He refused and continued fighting, even though he was already wounded, until he was shot. Apparently his last words were "I am dying with my country".

Aftermath and judgments

The war was a catastrophe for Paraguay that led the state and people to the verge of annihilation. Estimates of population losses range from half to four-fifths of the country's pre-war population; many of the survivors were disabled. After taking the capital, the victorious powers set up a government of opponents of López. In the following decades, in Paraguay, as in neighboring countries, the view of the victors dominated, López was described as a war criminal. In the 20th century a counter-movement began in Paraguay; In 1912, the Paraguayan historian Juan Emiliano O'Leary published a story of the war that glorified López as a national hero. This rating prevailed since the 1930s. Especially under the dictator Alfredo Stroessner , who ruled 1954-1989, the Paraguayan state practiced a hero cult around López. The remains of López are now buried alongside other Paraguayan soldiers and politicians in the national pantheon on the Plaza de los Héroes (Heroes' Square), López's face is adorned with the 1,000 guaraní banknote and the 1,000 guaraní coin that replaces it .

The judgments of the more recent serious historians have turned out differently up to the present day. There is agreement that López was overwhelmed by the tasks he had set himself, acted diplomatically ineptly and made serious political and military mistakes that contributed significantly to the defeat. His politics and warfare reveal no clear and realistic strategic goals; his most important decisions were mere reactions to the steps of his opponents. His determination to fight to the last man made no sense. On the other hand, his propaganda at home was very successful, with which he succeeded in mobilizing all human and material resources for the war.

Some historians emphasize the fact that under the López dictatorship economic life in Paraguay was largely controlled and dominated by the government - that is, the extremely wealthy López family. Therefore, European and American companies could do little in the Paraguayan market and were interested in overthrowing the dictator. Argentina, on the other hand, operated a liberal economic policy at the time. The British government has been accused of exerting significant economic influence in favor of the Allies, but with inadequate evidence.

The main issues at issue are the following:

- Some historians believe that López planned a war of aggression from the start with the intention of defeating the neighboring states and wresting parts of their territory from them. Others say he feared Brazil and Argentina would sooner or later intervene in Paraguay to overthrow him. According to this interpretation, he waged a preventive war out of fear for his rule. One thesis is that the Argentine President Miter cleverly provoked López to declare war and thus lured him into a trap.

- It is unclear to what extent there were actually conspiracies against López during the war. One view is that the dictator was morbidly suspicious and ordered the many executions of alleged or real opponents, also known as the "San Fernando massacre", on the basis of unfounded suspicions and accusations. The opposite thesis is that in the final phase of the war, parts of the Paraguayan state and army leadership actually planned a coup against López to replace him with one of his brothers and to end the war that had become hopeless.

literature

- Richard Francis Burton : Letters from the Battle-Fields of Paraguay , London 1870 (Facsimile reprint: University Press of the Pacific, Honolulu 2003, ISBN 1-4102-0448-0 )

- Heinz Joachim Domnick: The War of the Triple Alliance in German Historiography and Journalism , Frankfurt a. M. 1990, ISBN 3-631-42577-5

- Jürg Meister: Francisco Solano Lopez - national hero or war criminal? The War of Paraguay against the Triple Alliance 1864 - 1870 , Osnabrück 1987, ISBN 3-7648-1491-8

- Sian Rees: Elisa Lynch , Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-203-81501-X

- John H. Tuohy: Biographical Sketches from the Paraguayan War - 1864-1870 . CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform 2011, ISBN 978-1466248380 , pp. 11–14 (keyword: López, Francisco Solano )

Web links

- Literature by and about Francisco Solano López in the catalog of the German National Library

- Jan von Flocken : The greatest genocide of recent times. Welt Online from July 18, 2007.

Remarks

- ↑ Leuchars, Chris: To the bitter end: Paraguay and the War of the Triple Alliance , Westport (CT) 2002, pp. 10-12; Domnick, Heinz Joachim: The War of the Triple Alliance in German Historiography and Journalism , Frankfurt a. M. 1990, p. 14.

- ^ Crónica Histórica Ilustrada del Paraguay, Tomo II, Distribuidora Quevedo de Ediciones, Buenos Aires, 1998

- ↑ Leuchars p. 11.

- ↑ Tuohy p. 11.

- ↑ Leuchars pp. 11-12.

- ↑ Rees, Sian: Elisa Lynch , Hamburg 2003, pp. 22–35, 126; Leuchars p. 12f.

- ↑ Leuchars p. 13f .; Rees pp. 116-121.

- ↑ Leuchars p. 14, 31f .; Rees p. 131

- ↑ Leuchars pp. 19f., 25-29; Domnick p. 15; Rees p. 140f.

- ↑ Leuchars pp. 25-34.

- ↑ Leuchars p. 44f., Domnick p. 17

- ↑ Leuchars p. 166f.

- ↑ Leuchars pp. 64f., 94, 161f., 187f., 225; Rees pp. 177-180.

- ↑ Leuchars pp. 226-228, 231; Rees pp. 275f., 307f.

- ↑ Domnick p. 25; Leuchars p. 184; Rees pp. 261-278, 282f., 287-290.

- ↑ Leuchars p. 214; Domnick p. 25f.

- ↑ Leuchars pp. 224-230.

- ↑ Leuchars p. 230.

- ↑ Whigham, Thomas L./Kraay, Hendrik: Introduction , in: I Die with My Country. Perspectives on the Paraguayan War, 1864-1870 , ed. H. Kraay / Th.L. Whigham, Lincoln 2004, p. 19; Domnick p. 26; Leuchars p. 237.

- ↑ Rees p. 332f.

- ^ O'Leary, Juan E .: Historia de la guerra de la triple alianza , reprinted Asunción 1992.

- ↑ Rees pp. 5-8, 334-336.

- ↑ Leuchars pp. 24, 26, 29, 34.

- ↑ Leuchars p. 39f., 84.

- ↑ Leuchars pp. 34f., 41, 60f., 85.

- ↑ Domnick pp. 13, 16; Leuchars p. 159.

- ↑ Domnick p. 16.

- ↑ Whigham / Kraay p. 16; Leuchars p. 196.

- ↑ Domnick p. 15; Leuchars p. 12.

- ↑ Leuchars p. 32f.

- ↑ Domnick p. 16; Leuchars p. 40.

- ↑ Domnick p. 24f. u. Note 58; Rees pp. 216f., 241f., 251-253, 260-276.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Carlos Antonio López |

President of Paraguay 1862–1869 |

Cirilo Antonio Rivarola |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Solano López, Francisco |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Solano López Carrillo, Francisco |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | President of Paraguay |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 24, 1827 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | near Asunción , Paraguay |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 1, 1870 |

| Place of death | Cerro Corá , Paraguay |