Horned god

The British anthropologist Margaret Alice Murray called the Horned God a deity she assumed , who has been worshiped as the antithesis of the mother goddess since the Stone Age . She assumed a continuity of this duality , which ultimately also influenced the shape of the devil in Christianity in the form of a reinterpretation .

In the neo-pagan belief system of the Wicca cult, the Horned God forms the male counterpart of the Triune Goddess .

Margaret Murray

Murray argued that the depiction of the devil and witchcraft in Christianity was a distorted, polemical representation of the concepts and rites of an actual cult that had existed since prehistoric times, namely the worship of the goddess and the horned god, while they were the doings of the church persecuted witches interpreted as the last offshoot of this ancient cult.

She formulated this thesis, in which she referred to the work of the French historian Jules Michelet , for the first time in The Witch-cult in Western Europe , published in 1921 . Ten years later she published The God of the Witches, where she tried to historically underpin the concept of a horned god worshiped since the Stone Age . She started with the cave painting from the Grotto des Trois-Frères in France, known worldwide as the “shaman” or “sorcerer” , based on the sketch made by Henri Breuil .

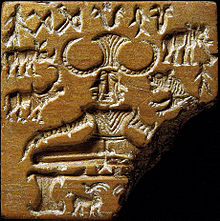

Murray then goes on to cite the numerous horn-bearing deities of the Bronze and Iron Ages in Mesopotamia and Egypt ; B. Amun wearing ram horns and Hathor of the Egyptians wearing cow horns, as well as the representation of a horned figure surrounded by animals, known as the lord of the (wild) animals , as shown by a seal from the ancient Indus culture of Mohenjo-Daro . A similar representation can be found on the much later Gundestrup boiler . Other horn-bearing figures are in the classical mythology of the Minotauros on Crete, as well as Pan and Dionysus Zagreus among the Greeks.

Finally Murray comes to speak of the Celtic god Cernunnos , who like the Stone Age shaman wears deer antlers. B. on an altar relief that is part of the Paris Nautenpfeiler found under the Cathedral of Notre-Dame . The name of the god (visible above the relief) is interpreted as "the horned one". Murray sees here evidence of the continuity of the cult of the Horned God from the end of the Ice Age to at least the Roman Empire.

From there she draws a link to the already Christianized Britain and quotes Theodor von Tarsus , Archbishop of Canterbury, who in his Liber poenitentialis at the end of the 7th century threatened anyone with a church penance of three years who dresses in animal skin, such as a deer or Bull walks around, and on to the witchcraft trials of modern times, from which Murray concludes: "This continuing belief in a horned deity shows that under the official religion of the rulers, an ancient cult with all its rites continued almost untouched."

However, this line of argument is sketchy, as it has not yet been possible to conclusively prove the existence of an “old cult with all its rites”. Attempts at (re) construction, as they have been undertaken again and again, for example by Carlo Ginzburg or Hans Peter Duerr in “Traumzeit” (1978), show time and again that a large proportion of Christian projection is faced with very little substantial information about the witchcraft , too little for a cult "with all its rites" that has existed continuously since the Ice Age.

Murray cites the Dorset Ooser , a pageant mask of unknown age, the wearer of which is dressed in animal skin, as one of the last offshoots of worshiping the horned . The mask disappeared at the end of the 19th century, but could still be entered into the Wicca cult and as a photograph in the Museum of Witchcraft by Cecil Williamson via Murray's book and via a wooden sculpture depicting Atho , which eventually also disappeared when it was stolen in 1967 Find. According to the English Wicca follower Charles Cardell , Atho was the actual name of the Horned God .

Wicca

The writings of Murray ultimately had a direct influence on the emergence of the Wicca cult. Gerald Gardner , the founder of Wicca had, according to his own account in 1939 admission to a coven ( English Coven ), the New Forest coven , found, its rites and doctrines which seemed to match what had read Gardner Murray about authentic old pagan cult . Since the members of the New Forest coven were also inspired by Murray, such a correspondence was not surprising. Gardner, however, believed he had come across one of the last surviving carriers of ancient pagan tradition.

Since he feared a complete extinction of the tradition, he decided to found new circles of witches. In order to make potential new members aware of his beginning, he sought publicity and published Witchcraft Today in 1954 as a representation of the rites and teachings that had become known to him. However, these were only very fragmentary, as he put it, which is why he added the material from other sources. In addition to Murray, these sources included the English occultist Aleister Crowley , with whom Gardner was known, Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches by Charles Godfrey Leland and writings related to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn . The main (double) source of inspiration is Murray, especially with regard to the Horned God . In the Wicca ritual, the god is embodied by a masked person who acts as a counterpart to the high priestess, who in turn embodies the Triune Goddess .

Like the Great Goddess , the Horned God also wanders through the cycle of the year:

- In spring he is born as a divine child of the Great Mother and passes his initiation. This also symbolizes the return of life.

- In summer , as a youthful god, he marries the virgin goddess in a holy wedding .

- In autumn he finally dies (and in death becomes ruler of the realm of the dead )

- and is reborn in winter , created by himself, at the beginning of a new cycle .

Literary implementations

The writings of Murray and the teachings of Wicca influenced numerous authors of modern fantasy literature. Another source of inspiration for the authors of fantastic literature was The White Goddess by the English poet Robert Graves . In this very idiosyncratic combination of Celtic myth, ancient mythology and poetic construction, the three-fold white goddess faces a god in the shape of a bull or deer, who becomes a victim, like Dionysus Zagreus, torn by titans, or Aktaion in Greek myth, torn by his dogs .

Murray follows a very similar line, but sees the background less mythological and poetic, but literally and practically in "holy kings" of the early days, who were slaughtered after a certain period in order to fertilize the fields with their blood. Both Murray and Graves refer to concepts from James Frazer's The Golden Branch, whose central thesis was based on the sacred murder of the priest-king of the sanctuary of Diana on Lake Nemi in ancient Italy, the rex nemorensis . It should be noted, however, that Frazer nowhere speaks about a Horned God in the sense of Murray, nor does the term appear in Graves.

The most popular work inspired by Murray, Graves and Wicca is a cycle of novels by Marion Zimmer Bradley . In “ The Mists of Avalon ” and its sequels, she takes on motifs from Murray's portrayal of the Horned God , embodied here by Arthur / Arthur .

literature

- Gerald Gardner: Witchcraft Today. Rider, London 1954.

- Gerald Gardner: The Meaning of Witchcraft. Aquarian Press, London 1959.

- Robert Graves: The White Goddess. Faber & Faber, London 1948.

- Margaret Murray: The Witch-cult in Western Europe. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1921.

- Margaret Murray: The God of the Witches. S. Low, Marston & Co., London 1931.

- Diane Purkiss: The Witch in History: Early Modern and Twentieth-Century Representations. Routledge, London 1996, ISBN 9780415087612 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jules Michelet: La Sorcière . 1862.

- ^ Murray: God of the Witches. Oxford University Press 1970, p. 23 f.

- ^ Murray: God of the Witches. Oxford University Press 1970, p. 29.

- ↑ Theodor von Tarsus: Liber poenitentialis, XXVII, 19. In: Benjamin Thorpe: Ancient laws and institutes of England, 1840, vol. 2, p. 34, digitized . The small detail that this church punishment threatens only those who disguise themselves in this way on the calendar of January is suppressed by Murray.

- ^ Murray: God of the Witches. Oxford University Press 1970, p. 34.

- ↑ Melissa Seims: The Coven of Atho.

- ↑ Gardner: Witchcraft Today, chap. 12.

- ↑ Göttner-Abendroth: The matriarchy. Volume II, 1, 1991 Kohlhammer Verlag, p. 56.

- ^ Murray: God of the Witches. Oxford University Press 1970, pp. 120 ff.

- ↑ See in particular the volume The Dying God (3rd edition 1911).