Mother goddess

Mother Goddess or Great Mother are names in archeology and religious history for historically proven or hypothetical earth goddesses in prehistoric and early historical cultures. They were worshiped as the giver of life ( fertility goddess ) or as mother of gods or both. Their representation can be found either in early written evidence or in works of art such as ancient wall paintings or Venus figurines . The interpretation of the non-written artifacts as "goddesses" is often speculative and therefore controversial.

The idea of the mother goddess is based on the idea of a female deity who has power over the soil and its inhabitants (human, animal, vegetable, but also possibly their inherent spirits). It is responsible for the fertility of plants, often also of animals, and thus crucial for the well-being of people. Mother goddesses are primarily documented for plant cultures, in which the earth as the origin of the plants was of central economic and religious importance.

The distinction between deities of sexual pleasure and goddesses of love - such as the Roman Venus , the Greek Aphrodite or the Mesopotamian Ištar and Inanna - is fuzzy . Deities who protect pregnant women and women in labor , such as the Greek Artemis or the ancient Egyptian Taweret and Bes , are not counted among the mother goddesses .

The different names for the "earth goddesses" of recent peoples and the "mother goddesses" of historical cultures are often used synonymously.

Differentiation to "Magna Mater"

Some authors use the Latin expression “ Magna Mater ” (great mother) across all ideas associated with mother goddesses, especially Manfred Ehmer in his popular scientific writings. However, this usage is misleading: Magna Mater is the name of the Romans for the goddess Cybele , whose mystery cult they had adopted from Asia Minor. In this respect, this expression only correctly stands for the ancient Mediterranean mother goddess. Since the popular religion of Asia Minor has always worshiped Cybele as mother goddess outside of a mystery cult, the term is sometimes also used up to its roots, presumed to be in the Neolithic.

origin

The oldest Neolithic depictions, which some authors have interpreted as mother goddesses, show them partly in connection with certain wild animals, so that prehistorians suspected the transitional form from the animal mistress of the older hunter cultures to the fertility goddess . The latter aspect became more and more important due to the increasingly agrarian way of life. Today, earth mother goddesses have a not inconsiderable, sometimes even dominant role in the respective religion in numerous traditional planter and farmer cultures .

distribution

The most famous Mother Goddess is the ancient Mater Deum Magna ideae - short Magna Mater - for the first time under the name of Cybele for the middle Bronze Age is occupied Asia Minor and their mystical cult to the Roman late antiquity ranges (see also: conceptual distinction from "Magna Mater " )

History of theory

The Swiss legal historian and classicist Johann Jakob Bachofen (1815–1887) was one of the first researchers to claim the existence of a hypothetical “primordial religion” centered on mother goddesses in his studies on “mother law” (1861). He referred mainly to the pre-classical cultures in Greece and Asia Minor . He saw the transition from maternal to paternal law societies as a decisive step forward in human history. Bachofen was supported by well-known anthropologists - many of whom were evolutionists like Edward Tylor (1871) and LH Morgan (1877) .

The Scottish anthropologist James George Frazer (1854-1941) described in his elfbändigen work The Golden Bough ( The Golden Bough , published from 1906 to 1915) as a religious pattern the king as a reincarnation of the dying and resurrected God, who in a " sacred marriage " with the goddess, who represented and guaranteed the continued fertility of the earth, is conceived again and again after he had died with the harvest in the past year. Frazer led, among others, the pairs Attis-Kybele , Dumuzi - Inanna , Tammuz - Ištar and Adonis - Aphrodite , whose myths all followed this basic pattern. Bachofen and Frazer's assumptions led to major scientific debates and are still highly controversial today (compare Horned God ).

The English writer Robert von Ranke-Graves (1895–1985) developed the cult of a “white goddess”, a goddess of love and wisdom, who also inspired poetry, from the mythology of Greece and Asia Minor.

The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) attacked the idea of a primordial or universal mother in his analytical psychology on to the mother archetype to call. Research on this archetype was carried out by the psychologist Erich Neumann ( The Great Mother , 1956) and the British anthropologist EO James ( The Cult of the Mother-Goddess , 1959).

The Lithuanian archaeologist Marija Gimbutas (1921–1994) accepted the veneration of a single, abstract “Great Goddess” for Southeastern Europe and the lower Danube region - she referred to as “ Old Europe ” - for the Neolithic period and carried this out in her works of Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe (English 1974, German 2010), The Language of the Goddess (English 1989, German 1995) and The Civilization of the Goddess (English 1991, German 1996). Her assumption was based primarily on numerous female figurines from the Neolithic and the Copper Age , which she interpreted as depictions of this one deity.

Interpretation of archaeological finds

While Michael Dames equates the cult of the mother goddess with that of the great mother of the Neolithic in connection with the spread of agriculture associated settling of people ("The great goddess and the Neolithic belong together in as natural a way as mother and child"), authors like the psychologist Erich Neumann based on an archaic cult of the mother goddess that goes back tens of thousands of years.

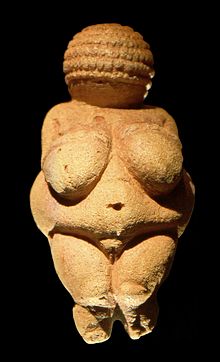

Old Stone Age

Finds of 100 to 200 Upper Palaeolithic so-called Venus figurines (Venus statuettes) with a maximum size of 15 cm and other depictions of female bodies with pronounced breasts, oversized hips and other prominent sexual characteristics are used as evidence for this thesis. Most come from the time between 28,000 and 21,000 before our time ( Gravettia ) from the area north of the Pyrenees , southern Central Europe, Italy and southern Eastern Europe, such as the approximately 27,000 year old Venus von Willendorf . These figures have been interpreted as evidence of a general admiration for mother earth and her fertility. There are also a number of male figurines that received significantly less attention.

From a scientific point of view, however, it is now assumed that there are no goddesses, priestesses or fertility cults that could illustrate these figurines . This is justified, among other things, by the fact that there are generally no gods in non-stratified societies and that fertility is not a desirable good for hunter and gatherer cultures . Due to the high need for care of children, such societies are mostly familiar with contraceptive methods. In addition, there are no mother-child representations that could indicate a mother cult.

The latest find at the foot of the Swabian Alb from 2008, the Venus vom Hohlefels , comes from the Aurignacia at the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic at an age of 35,000 to 40,000 years . During this time, modern humans ( Homo sapiens ) immigrated to Europe as Cro-Magnon humans . In this figurative representation, the female lap is emphasized by an oversized representation of the labia , unless it is an anatomical feature that is also found in other paleolithic Venus figurines and was described as the " Hottentot apron " in the 19th and early 20th centuries . Other statuettes from the same time horizon show animals and hybrid beings ("lion man"). Archaeologist Joachim Hahn interprets them as symbols of strength and aggression, and Martin Porr as media of social memory.

Neolithic and Copper Age

The wall paintings, figurines and burials in the excavations of Çatalhöyük in Anatolia , begun by James Mellaart in the 1960s and continued by Ian Hodder , have been attempted to interpret since the 1970s , especially in spiritual feminism and by supporters of a matriarchal idea , as evidence of a worship of mother goddesses.

Neolithic and Copper Age figurines from southeast Europe and Egypt were also used as evidence of the cult of a mother goddess.

In the 1950s, Osbert Crawford combined Ǧemdet-Nasr- era eye figures from Tell Brak with the mother goddess and thus constructed a further spread of the cult of an "eye goddess".

However, since the 1960s, these theories have been largely rejected from a scientific point of view.

Mythological background

Ideas about a cult of the mother goddesses are based on myth constructions of the 19th century about the great goddess, which were associated with statuettes from the Paleolithic and Neolithic . As the British prehistorian Andrew Fleming noted in 1969, such theories usually reveal more about the worldview of their representatives than about prehistory.

Many myths reconstructed in this way connect, according to the basic pattern claimed by Frazer, the fate of the gods, who were conceived in the “holy marriage” ( hieros gamos ) by the departing god (consort-son-lover), by the goddess, with the annual revival of nature born and destined to be her lover, which ensured growth. Thus the mother goddess immediately becomes the mother of a god who came to God himself (through rebirth) and passed away through death, not without the certainty of being reborn by the goddess. In this way the goddess guaranteed fertility and the everlasting cycle of life. There are various deviations from this pattern in myths, but they all close the same cycle: birth-growth-maturity-death and rebirth.

Mother goddesses of different cultures

Many cultures , of which or about which there are written records, know female deities, some of which are accompanied by an idea of a mother earth and fertility goddesses :

Northern Europe

- The Germanic tribes worshiped the maternal earth under the name Nerthus , which Tacitus reported. Eugen Drewermann interprets Frau Holle as a representation of the goddess Perchta , whom he called the great goddess .

- Sif was the Viking goddess of harvest . and Jörd the earth goddess of Norse mythology.

- Under the name Brighid , the Celts in Ireland worshiped a fertility and vegetation goddess who was regarded as a female earthly force. With the Celtic tribes in Noricum , the same was true of Noreia .

- The ancient Celts and Romans as well as the Germanic tribes in the first centuries after the turn of the century also worshiped so-called matrons in groups of three as mother goddesses.

- According to Marija Gimbutas, a fertility and vegetation goddess was worshiped by the Baltic as Māra , Laima , Žemyna and others.

- The Slavic mother goddess was the mostly formless Mati Syra Zemlya ("Moist Mother Earth"). Mokosch is known as another earth goddess of the Slavs .

- The Finnish Kalevala epic describes a creation myth based on the original mother Ilmatar .

Mediterranean area

- The ancient Egyptian goddess Hathor was the outstanding mother goddess in her appearance as the heavenly cow before she merged with Isis , the mother of Horus . It is often portrayed as suckling and represents the fertility of the herds. In the Egyptian creation story, Isis is conceived by Geb , the early earth god, and Nut , the early sky goddess. The figures of Hathor and Isis are associated with the Mediterranean Magna Mater cult.

- The goddesses Gaia , Rhea , Dia , Hera and Demeter are mother goddesses from the Greco-Asia Minor area. Kubaba , which was later revered as Cybele , also comes from the Middle East .

- Tanit was the Punic goddess of fertility, an apotheosis of the Phoenician goddess Astarte and patron goddess of Carthage.

Middle East

- The German psychologist Gerda Weiler took the view that traces of female deities could be found in the Old Testament .

- In Mesopotamia there was a syncretistic mother goddess who had many names, such as Sumerian Diĝirmaḫ, Nindiĝirene or Ninḫursaĝa , Akkadian Bēlet-ilī, as well as Nintur, Aruru, Mam (m) a / Mam (m) i, Ninlil and Damgalnunna / Damkina.

- The mother goddess of the Hittites and Hattier was Ḫannaḫanna , whose helper was a bee.

- Uraš - "the earth" - comes from Sumerian mythology .

- The ancient Arabic moon goddess al-Lat was also the earth goddess of Arabia.

South and East Asia

- For India the Atharvaveda , a collection of hymns of Hinduism compiled at the end of the 2nd or beginning of the 1st millennium, is cited as evidence of the worship of a female primordial goddess as Mother Earth.

- Prithivi was an Indo-European earth goddess in the shape of a cow who was equated in India with the Hindu earth goddess Bhudevi.

- In Hinduism today there are a multitude of goddesses who also have maternal functions, such as Mahadevi , Durga , Kali , Lakshmi and Parvati .

Neopaganism

Followers of new natural religions and the idea of a prehistoric matriarchy associate the findings of the Venus statuettes from the time of the Upper Paleolithic with a general worship of mother earth in the sense of an anthropomorphic mother goddess.

literature

- Andrew Fleming : The Myth of the Mother-Goddess. In: World Archeology. Volume 1, No. 2: Techniques of Chronology and Excavation. 1969, pp. 247–261 ( PDF file; 977 kB; 16 pages on stevewatson.info).

- Lucy Goodison , Christine Morris (Eds.): Ancient Goddesses. The Myths and the Evidence. British Museum Press, London 1998, ISBN 0-7141-1761-7 .

- Wolfgang Helck : reflections on the great goddess and the deities connected to her (= religion and culture of the ancient Mediterranean world in parallel research. Volume 2). Oldenbourg, Munich / Vienna 1971, ISBN 3-486-43261-3 .

- Lynn Meskell: Goddesses, Gimbutas and "New Age" Archeology. In: Antiquity. Volume 69 = No. 262, 1995, ISSN 0003-598X , pp. 74-86.

- Kathryn Rountree: Archaeologists and Goddess Feminists at Çatalhöyük. An experiment in multivocality. In: Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion. Volume 23, No. 2, 2007, ISSN 8755-4178 , pp. 7-26.

- Maria Xagorari-Gleißner: Meter Theon. The mother of gods among the Greeks. Rutzen, Mainz a. a. 2008, ISBN 978-3-938646-26-7 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bettina Schmidt: Erdherr (in), keyword in: Walter Hirschberg (founder), Wolfgang Müller (editor): Dictionary of Ethnology. New edition, 2nd edition, Reimer, Berlin 2005, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ Manfred Kurt Ehmer: The wisdom of the West. 1998 Düsseldorf, Patmos, ISBN 3-491-72395-7 , p. 46.

- ↑ Hanns Ch. Brennecke, Christoph Markschies, Ernst L. Grasmück (ed.): Logos: Festschrift for Luise Abramowski on July 8, 1993. Edition, publisher, place year, ISBN, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Klaus E. Müller: The better and the worse half. Ethnology of the gender conflict. Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York 1984, ISBN 3-593-33360-0 , pp. 272-277.

- ↑ Karl Meuli (ed.), Johann Jakob Bachofen : Das Mutterrecht. First half, Volume 2, Schwabe, Basel 1948, p. 26 ff (1st edition 1861).

- ^ Edward Burnett Tylor: Primitive Culture. Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Language, Art, and Custom . J. Murray, London 1871; German edition: The beginnings of culture. Studies on the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art and custom . Georg Olms, Hildesheim 2005.

- ^ Lewis Henry Morgan: Ancient Society; or, Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilization . H. Holt, New York 1871.

- ↑ a b Lauren Talalay: “The Mother Goddess in Prehistory. Debates and Perspectives ”. In: Sharon L. James, Sheila Dillon (Eds.): A Companion to Women in the Ancient World . Blackwell, Oxford 2012, p. 8.

- ↑ Robert von Ranke-Graves : Greek Mythology. Anaconda, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-86647-211-2 , pp. ??; the same: The white goddess, language of myth. 1958, ISBN 3-499-55416-X , p. ?? (English original: 1949).

- ↑ Erich Neumann: The great mother. A phenomenology of the female form of the unconscious . Rhein-Verlag, Zurich 1956.

- ↑ Edwin Oliver James: The Cult of the Mother-Goddess. An Archaeological and Documentary Study . New York, 1959.

- ↑ Michael Dames: The Silbury Treasure. New edition. Thames & Hudson, London 1978, ISBN 978-0-500-27140-7 , pp. ??; compare also Harald Haarmann: The Madonna and Her Daughters. Reconstruction of a cultural-historical genealogy. Olms, Hildesheim / Zurich / New York 1996, ISBN 3-487-10163-7 , pp. 25-26.

- ↑ Erich Neumann : The great mother. A Phenomenology of the Female Forms of the Unconscious. Rhein, Zurich 1956, pp. ??; AT man, Jane Lyle : Sacred Sexuality. Vega, London 2002, ISBN 1-84333-583-2 , p. 18.

- ↑ Distribution map of the sites of Venus statuettes 34,000–24,000 BP; Siegmar von Schnurbein (ed.): Atlas of the prehistory. Europe from the first humans to the birth of Christ. Theiss, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-8062-2105-3 , pp. 28-29.

- ↑ Manfred Kurt Ehmer: Goddess Earth. Cult and myth of mother earth. Zerling, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-88468-058-7 , p. 22; Franz Sirocko (Ed.): Weather, Climate, Human Development. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-534-22237-7 , p. 79 (see Gesine Hellberg-Rode: Mother Earth in the Paleolithic. In: Project Hypersoil. University of Münster 2002–2004).

- ↑ Compare Jan Jelínek : The great picture atlas of humans in prehistoric times. Artia, Prague 1980, pp. ??.

- ↑ Margaret Ehrenberg: Women in Prehistory (= Oklahoma Series in Classical Culture. Volume 4). University of Oklahoma Press, Norman et al. a. 1989, ISBN 0-8061-2237-4 , p. 74.

- ^ Brigitte Röder , Juliane Hummel, Brigitta Kunz: Göttinnendämmerung. The matriarchy from an archaeological point of view. Röder, Munich 1996, p. 202.

- ^ Luce Passemard : Les statuettes féminines paléolithiques dites Vénus stéatopyges. Librairie Teissier, Nîmes 1938, p. ??.

- ↑ Joachim Hahn: Strength and Aggression. The message of Ice Age art in the Aurignacia of southern Germany? Archaeologica Venatoria - Institute for Prehistory of the University of Tübingen, Tübingen 1986, p. ??.

- ^ Martin Porr: Palaeolithic Art as Cultural Memory. A Case Study of the Aurignacian Art of Southwest Germany. In: Cambridge Archaeological Journal. Volume 20, No. 1, 2010, pp. 87-108, here pp. ??.

- ↑ For more recent critical literature on Çatalhöyük, see Lynn Meskell , Twin Peaks: The Archaeologies of Çatalhöyuk. In: Lucy Goodison; Christine Morris, Ancient Goddesses: The Myths and the Evidence. British Museum Press, London 1998, pp. 46-62; Lynn Meskell: Goddesses, Gimbutas and "New Age" Archeology. In: Antiquity. Volume 69 = No. 262, 1995, pp. 74-86; Kathryn Houtitree: Archaeologists and Goddess Feminists at Çatalhöyük. In: Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion. Volume 23, No. 2, 2007, pp. 7-26.

- ^ Osbert GS Crawford : The Eye Goddess. Phoenix House, London 1957, pp. ??.

- ↑ Peter J. Ucko : Anthropomorph Figurines of Predynastic Egypt and Neolithic Crete, with comparative material from the prehistoric Near East and mainland Greece. Occasional paper of the Royal Anthropological Institute 24, London 1968, pp. ??; Andrew Szmidla for Egypt and Greece; comprehensive for the Balkans: Douglass Whitfield Bailey : Prehistoric Figurines. Representation and Corporeality in the Neolithic. Routledge, Abingdon 2005.

- ↑ Andrew Fleming : The Myth of the Mother-Goddess. In: World Archeology. Volume 1, No. 2: Techniques of Chronology and Excavation. 1969, pp. 247–261, here p. 247 ( PDF file; 977 kB; 16 pages on stevewatson.info): “It is probable that such statements reveal more about the faith of prehistorians than about that of the megalith builders; there is in fact an urgent need to re-examine the whole hypothesis. "

- ↑ Joe J. Heydecker : The sisters of Venus. The woman in myths and religion. Heyne, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-453-07824-1 , p. 77 ( Inanna ), p. 87 f. ( Ishtar ), p. 163 ff. ( Demeter - Persephone ), also Harald Haarmann : The Madonna and Her Daughters. Reconstruction of a cultural-historical genealogy. Olms, Hildesheim et al. 1996, ISBN 3-487-10163-7 , p. 138 ff.

- ↑ Harald Haarmann: The Madonna and Her Daughters. Reconstruction of a cultural-historical genealogy. Olms, Hildesheim et al. 1996, ISBN 3-487-10163-7 , p. 25.

- ↑ Tacitus Germania, Chapter 40.

- ↑ Philip Wilkinson: Myths & sagas from all cultures. Origins, tradition, meaning. Dorling Kindersley, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-8310-1503-0 , p. 96.

- ↑ Manfred Kurt Ehmer: Goddess earth, cult and myth of mother earth. Zerling, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-88468-058-7 , p. 68 f.

- ^ Bernhard Maier : Lexicon of Celtic Religion and Culture (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 466). Kröner, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-520-46601-5 , p. 252.

- ↑ Philip Wilkinson: Myths & sagas from all cultures. Origins, tradition, meaning. Dorling Kindersley, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-8310-1503-0 , p. 115.

- ↑ R. Deroletz: Gods and Myths of the Teutons. F. Englisch, Wiesbaden 1976, pp. 171-177.

- ^ Marija Gimbutas: The Language of the Goddess. London, Thames and Hudson 1989, pp. ??.

- ↑ Philip Wilkinson: Myths & sagas from all cultures. Origins, tradition, meaning. Dorling Kindersley, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-8310-1503-0 , p. 143.

- ^ A b Philip Wilkinson: Myths & sagas from all cultures. Origins, tradition, meaning . Dorling Kindersley, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-8310-1503-0 , p. 110.

- ↑ Manfred Kurt Ehmer: Goddess earth, cult and myth of mother earth. Zerling, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-88468-058-7 , pp. 55-56.

- ↑ Gerda Weiler : The matriarchy in ancient Israel. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-17-010773-9 , p. ??.

- ↑ a b Manfred Krebernik: Gods and Myths of the Ancient Orient. Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-60522-2 , pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Volkert Haas : The Hittite literature. Gruyter, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-11-018877-6 , pp. 98, 106 ff., 116, 120, 198 and 205.

- ↑ Philip Wilkinson: Myths & sagas from all cultures. Origins, tradition, meaning. Dorling Kindersley, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-8310-1503-0 , p. 181.

- ↑ Manfred Kurt Ehmer: Goddess earth, cult and myth of mother earth. Zerling, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-88468-058-7 , p. 31 ff.

- ↑ B. Marquardt-Mau: Mother Earth. In: M. Schächter (Ed.): Right in the middle - the earth has no thick skin. Mann-Verlag, Berlin 1988, pp. 85-95. Summary available .