Sumerian language

| Sumerian (proper name: ?? eme-ĝir "native language") | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

formerly in Mesopotamia | |

| speaker | extinct | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | - | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

sux |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

sux |

|

The Sumerian language is the language of the ancient oriental cultural people of the Sumerians . According to previous knowledge, it is not related to any other known language, which is why it is called linguistically isolated . According to the grammatical structure, it is a (predominantly drinking ) agglutinating language . Sumerian was spoken in southern Mesopotamia mainly in the third millennium BC. Chr. Its beginnings, however, are in the dark. No later than 2000 BC. It was probably only used as a second language. From the end of the Old Babylonian period in the 17th century BC. Then it became completely extinct as a spoken language. Nevertheless, it lived as the language of scholars in religion, literature and science in all of Mesopotamia until the 1st century BC. Chr. Continued. As far as we know today, Sumerian is the first language for which a script was developed (around 3300 BC). Their written tradition therefore covers a period of around 3000 years.

Note: When writing the Sumerian words, the grapheme variants (different cuneiform characters) are omitted and a normalized form without accents and indices is used instead (also Zólyomi 2005). This form of representation makes it much easier for those who are not familiar with cuneiform to understand the linguistic aspects that are the main issue here.

Sumerian - an isolated ancient oriental language

The oldest written language

At least since around 3500 BC. The Sumerians in southern Mesopotamia played a decisive role in the transition to high culture , especially in the development of a script useful for business and administration around 3200 BC. BC (finds in Uruk IVa). This is the world's oldest writing development, only the first Egyptian hieroglyphs come close to the age of Sumerian writing. Whether there was a relationship between the two oldest writing systems by far is a hitherto unanswered question in Egyptology and Ancient Near Eastern Studies .

Around 3200 BC In the 2nd century BC, people started to scratch the patterns, which had been scratched on clay counters, into larger lumps of clay and to provide them with additional characters. From this archaic form the Mesopotamian cuneiform developed to full bloom in a few centuries - so named after the shape of its characters, which were created by pressing an angular stylus into the soft clay. It is preserved on clay tablets and other supports such as statues and buildings that were discovered during archaeological excavations in Mesopotamia. This writing adapted the Akkadians , Babylonians , Assyrians , Eblaiter , Elamites , Hittites , Hurrians and Urartu each for their own language.

The Sumerian cuneiform was originally developed as an ideographic or logographic writing. Each sign corresponded to a word, and these signs initially made it easy to see which term was meant. In the course of a few centuries, a form of syllable representation was developed based on the rebus principle , in which many characters were assigned one or more phonetic syllable values (mostly V, KV, VK, KVK) (V for vowel, K for consonant). A logographic-phonological script was developed.

Using the example of the following short text, a brick inscription by the city prince Gudea of Lagaš (around 2130 BC), the terms of transliteration of cuneiform and its decomposition in grammatical analysis are illustrated.

| Cuneiform |

|

|

|

| Transliteration | diĝir inana | nin-kur-kur-ra | nin-a-ni |

| analysis | d Inana | nin + kur + kur + ak | nin + ani + [ra] |

| Glossing | Inana | Mistress-Land-Land-GENITIVE | Mistress-his- [DATIVE] |

|

|

|

|

| gu 3 -de 2 -a | pa.te.si | šir.bur.la ki |

| Gudea | ensi 2 | Lagas ki |

| Gudea | City Prince | von-Lagas |

|

|

| ur-diĝir-ĝa 2 -tum 3 -du 10 -ke 4 |

| ur + d Ĝatumdu + ak + e |

| Hero (?) - der-Ĝatumdu (Ergative) |

|

|

|

| e 2 -ĝir 2 -su.ki.ka-ni | mu-na-you 3 |

| e 2 + Ĝirsu ki + ak + ani | mu + na + n + you 3 |

| his-temple-of-Ĝirsu | has-he-built-her |

Remarks: diĝir and ki are determinants here , they are superscripted in the analysis; pa.te.si and šir.bur.la are diri -composites .

Translation: For Inana , the mistress of all lands, his mistress, Gudea, the city prince of Lagas and hero (unsure) of the Ĝatumdu , built his house of Ĝirsu .

The Sumerian script and questions of transcription and transliteration are not discussed further in this article, reference is made to the article Cuneiform .

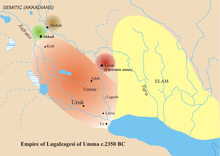

Sumerian-Akkadian coexistence

Sumerian played the main role in southern Mesopotamia throughout the third millennium - interrupted only during the time of the Semitic Empire of Akkad (2350–2200 BC). However, the Sumerians had to fight since about 2600 BC BCE increasingly deal with Semitic competition (the Akkadians, first in northern Mesopotamia), whereby one should assume less of a hostile position of the two population groups than of a largely peaceful assimilation and integration process, which ultimately leads to a coexistence of these peoples and theirs Languages led (the Sumerian- Akkadian linguistic area of convergence with mutual linguistic influence; see Edzard (2003)). At least since 2000 BC BC - according to others as early as the early III period - Sumerian slowly lost its importance as a spoken language, the Sumerian ethnic element gradually merged with the Semitic population, which was growing - also through further immigration. Around 1700 BC BC, no later than 1600 BC BC, Sumerian ended as a spoken language. It was used for a long time as the language of cult, science, literature and official royal inscriptions. The last Sumerian texts come from the final phase of the cuneiform epoch (around 100 BC).

Speech periods and types of text

The three thousand year history of the Sumerian language is divided into the following periods:

- Archaic Sumerian or Early Sumerian 3100–2600 BC From this period almost only economic and administrative texts come from, finds mainly from Uruk (phase IVa and III) and Šuruppak . There are some legal documents and literary compositions in archaic form from the Jemdet Nasr period . Since the grammatical elements - markings of grammatical functions in nouns and verbs - were only written sporadically, the texts do little to illuminate the grammatical structure of Sumerian.

- Old Sumerian 2600–2150 BC Mainly economic and administrative texts, first long royal inscriptions, isolated literary texts. The main site is Lagaš . The texts of this phase already give some information about Sumerian grammar. After the time of the Semitic Akkadian Empire (2350–2200 BC), which was accompanied by a sharp decline in Sumerian material, the Sumerian Renaissance came about.

- Neusumerisch 2150-2000 v. The greatest density of finds from the time of the III. Ur dynasty(Ur III period), countless economic texts from Lagaš , Umma and Ur . A number of legal and procedural documents have been handed down. The extensive building hymns by Ensis Gudea von Lagaš (around 2130 BC), which have beenhanded down on cylinders, are of central importanceand allow a fundamental grammatical analysis of Sumerian (A. Falkenstein (1949/78)).

- Late Sumerian 2000–1700 BC Use of Sumerian as a spoken language in parts of southern Mesopotamia ( Nippur region ), but above all intensively as a written language for legal and administrative texts and royal inscriptions (often bilingual Sumerian-Akkadian). Many literary works that had been handed down orally from earlier times found their Sumerian written form for the first time, including the Sumerian version of some parts of the famous Gilgamesh epic .

- Post-Sumerian 1700–100 BC Sumerian was no longer used as a spoken language and was largely replaced as a written language by Akkadian (Babylonian in the south, Assyrian in northern Mesopotamia), it only played the role of a scholarly, cult and literary language. Their long-lasting importance shows the fact that in the 7th century BC The Assyrian King Ashurbanipal excels at reading Sumerian texts. A large part of the bilingual lexical lists (Akkadian-Sumerian), which first made access to the Sumerian language possible in the 19th century, also originate from the post-Sumerian period.

Dialects and sociolects

Although a later lexical text lists a number of dialects (better: sociolects ) of Sumerian, besides the normal language eme-gi (r) only the sociolect eme-sal remains tangible, even if only in late Sumerian literary tradition. This form of language was mainly used when female characters have their say in literary texts, while narrative parts and the speeches of men are written in normal language. The main differences to normal language are a partial phonetic redesign of the word roots and morphological formation elements , but also the use of words that do not occur in the main dialect (for example mu-ud-na instead of nital "consort", mu-tin instead of ki-sikil "virgin").

The rediscovery of Sumerian

At the turn of the ages all knowledge of Sumerian and cuneiform was lost. In contrast to the Assyrians, Babylonians and Egyptians, whose work is well documented in the historiography of classical antiquity, there is no reference to the existence of the Sumerians in these reports. With the deciphering of the cuneiform script since the beginning of the 19th century, three languages were initially discovered: the Semitic Akkadian (in its Babylonian form), the Indo-European Old Persian and Elamish (an isolated language in the southwest of present-day Iran). Only later was a fourth language recognized among the Babylonian texts, which Jules Oppert was the first to describe in 1869 as “Sumerian” (after Akkadian šumeru ). The Sumerians' self-designation for their language was eme-gi (r) , which may mean "native language"; they called their country kengir . The existence and naming of the language were, however, controversial for a long time and could only be verified 20 years later after the discovery of bilingual texts in Nineveh and the abundant text finds in Lagaš by the archaeologists Ernest de Sarzec and Léon Heuzey of François Thureau-Dangin . The latter finally opened up the Sumerian language for scientific research with his work "The Sumerian and Akkadian Royal Inscriptions" (1907).

Relationships with other languages

There have been numerous attempts to relate Sumerian to other languages or language families . So far, none of these suggestions has convinced the professional world. Thus, the majority of Sumerian continues to be viewed as an isolated language. If there were languages related to Sumerian in prehistoric times, they were not written down and therefore lost for comparison.

Sumerian as a language in the Dene-Caucasian macro family

In the current discussion of macro families , some researchers, according to John D. Bengtson (1997), consider Sumerian to be a candidate for the Dene-Caucasian macro-family, which includes Sino-Tibetan , North Caucasian , Yenis and Na-Dené languages , In addition, the languages Burushaski , Basque and Sumerian , which are otherwise regarded as isolated, are also included.

Predecessors and neighbors of the Sumerians

Whether the Sumerians in southern Mesopotamia were autochthonous or whether they immigrated in the course of the 4th millennium cannot be determined with any certainty. It is very difficult to relate a possible occurrence of the Sumerians in southern Mesopotamia to certain archaeological horizons or developments. The older Sumerian linguistic research (for example Falkenstein) assumed that the Sumerians in southern Mesopotamia were not autochthonous, but only immigrated there in the 4th millennium and overlayed a pre-existing population there. This was tied to a so-called pre-Sumerian language substrate (sometimes called “ protoeuphratic ”). The city names that cannot be explained in Sumerian such as Ur , Uruk ( Unug ), Larsa and Lagaš , god names such as Nanše and Gatumdu , but also agricultural terms such as apin “plow”, engar “plowman”, ulušin “ emmerbier ”, nimbar “date tree ” should come from this layer ”, Nukarib “ gardener ”, taskarin “ boxwood ”and names from the field of metal processing such as simug “ blacksmith ”and tibira “ metal worker ”, which of course raises some questions for the cultural status of the Sumerians when they immigrated to Mesopotamia.

Today, a “pre-Sumerian” interpretation of the above examples is by no means considered safe, as there is a lack of precise knowledge of what a “Sumerian” or a “non-Numeric” word might have looked like in the first half of the 3rd millennium. In particular, polysyllabic words were considered "unsumeric" in early research, but this is viewed by other authors as an unsuitable criterion. G. Rubio (1999): “There is no uniform substrate that has left its mark on the Sumerian lexicon. All you can discover is a complex network of borrowings , the direction of which is often difficult to determine. ”Gordon Whittaker (2008), however, assumes that Sumerian has a substrate that he classifies as Indo-European .

The Sumerians gradually entered into a symbiosis with the Semitic Akkadians already mentioned, which of course also had reciprocal effects on the two languages. This concerns the word order in the sentence, phonetics , the case system , especially mutual borrowings : about 7% of the Akkadian vocabulary are borrowings from Sumerian, but Sumerian also had an Akkadian share of three to four percent in the later periods (Edzard (2003) ).

In addition, the Elamites in the Chusistan area on the Persian Gulf (today southwest Iran) should be mentioned, whose culture and economy have been influenced by the Sumerian civilization since the beginning of the 3rd millennium. This also had an impact on the Elamite writing systems, as in addition to in-house developments, writing forms from Mesopotamia were also adopted and adapted. A reverse influence of Elam on Sumer can hardly be proven.

An influence on the Sumerian language by "foreign peoples" - Lulubians , Guteans and others who ruled Sumer in phases in the 3rd millennium - is also not tangible, if only because the languages of these ethnic groups are virtually unknown.

Language type

Preliminary remark

This brief presentation of the Sumerian language concentrates on the nominal and verb morphology , only the grammatical standard phenomena are dealt with, exceptions and special cases are only mentioned sporadically. The presentation is mainly based on the grammars of DO Edzard (2003) and G. Zólyomi (2005).

In the representation of the Sumerian forms, the grapheme variants (different cuneiform characters) are omitted and instead a normalized form without accents, indices and phonetic supplements is used (also Zólyomi 2005). This method makes it much easier for those who do not know the cuneiform to understand the linguistic aspects that are the main focus here.

Grammatical construction

Sumerian can be briefly characterized as an agglutinating split-ergative language with grammatical gender (person and subject class). (Split-ergativity means that the ergative construction - it is explained below - is not used throughout, but rather the nominative-accusative construction known from European languages occurs in certain contexts.) The verb is at the end of the sentence, the position of the other parts of the sentence is attached depends on various factors, noun and verb phrases are closely interlinked.

There is no expression of the noun versus verb parts of speech , the same stems (roots) - many are monosyllabic - can be used for both functions. For example, dug means both “speech” and “speak”. The respective function is made clear by the function markers ( morphemes which mark grammatical functions) and the position in the sentence, the stems remain unchanged. In particular, there are no infixes (such as in Akkadian).

Difficulties in determining inventory of sounds and forms

The ambiguity ( homophony ) of many syllables of the cuneiform script used for Sumerian could suggest that Sumerian was a tonal language in which different pitches differentiated meanings. However, the fact that there are no other tonal languages in the Middle East speaks against it. It is also possible that a greater wealth of phonemes than that which can be reconstructed from writing today is masked by the deficits of this writing system.

Since Sumerian was extinct for a long time and was handed down in a writing system that was often not clearly interpretable, phonology and morphology can only be roughly described, which can also explain why there are still very different theories about verb morphology (in particular the prefix system of the finite verb ) .

Phonemes

The phoneme inventory is - as far as can be seen from the script - quite simple. The four vowels / aeiu / have 16 consonants opposite:

| Transliteration | b | d | G | p | t | k | z | s | š | H | r | r̂ | l | m | n | G | |||

| pronunciation | p | t | k | pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | ʦ | s | ʃ | x | r | (?) | l | m | n | ŋ |

The phoneme / r̂ / (or / dr /) is read by B. Jagersma and G. Zólyomi as an aspirated dental affricata [ʦʰ]. Since it appears as [r] in Akkadian loanwords , this analysis is debatable.

Many scientists (including Edzard (2003)) assume the existence of an / h / phoneme. Its exact pronunciation, whether laryngeal or pharyngeal , is just as unclear as the question of other phonemes.

Nominal morphology

Person and material class

Sumerian has a grammatical gender that distinguishes between a “person class” (abbreviation PK or HUM) and a “factual class”, more precisely “non-person class” (abbreviation SK or NONHUM). Animals usually belong to the "class". This two-class system has effects on conjugation and plural formation, among other things . The grammatical gender of a word cannot be seen formally.

Plural formation

Sumerian has two numbers , the unmarked singular and a plural . The plural is only marked for the nouns of the person class, the plural marker (morpheme to mark the plural) is optional and reads / -ene /, after vowels / -ne /. The marking is omitted for number attributes, the plural remains unmarked for nouns of the subject class.

The plural can - also in addition to the marker - be formed by putting the noun or the following adjective attribute twice. The attribute -hi.a (actually participle of hi "mix") can take on the function of pluralization in nouns of the subject class .

Examples of plural formation

| Sumerian | German |

|---|---|

| diĝir-ene | the gods (PK) |

| lugal-ene | the kings (PK) |

| lugal-umun | seven kings ( marker is omitted because number word is available ) |

| bath | die Mauer (sg), die Mauern (pl) (SK, therefore without marking ) |

| you-you | the words, all the words (totalization) |

| cure-cure | the mountains, foreign lands; all mountains, foreign lands |

| šu-šu | hands |

| a-gal-gal | the big ( gal ) water ( a ) |

| udu-hi-a | various sheep (SK) |

Ergativity

Sumerian is an ergative language . So it has different cases for the agent (the subject) of the transitive verb and the subject of the intransitive verb. The first case is called ergative , the second absolute , it is also used for the object (the patient) of transitive verbs.

- Ergative > agent (subject) transitive verbs

- Absolute > subject of intransitive verbs and direct object (patient) of transitive verbs

Examples of ergative construction (the verb forms are explained in the section Verbal morphology )

| Sumerian | German | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| lugal-Ø must-ĝen-Ø | the king ( lugal ) came ( must ) | intransitive verb: subject ( lugal ) in the absolute |

| lugal-e bad-Ø in-sig-Ø | the king tore down ( in-sig-Ø ) the wall ( bad ) | transit. Verb: agent ( lugal-e ) in the ergative, obj. ( Bad ) in the absolute |

Since this ergative construction is not consistently used in Sumerian, but rather the nominative-accusative construction is sometimes used, one speaks of "split ergativity" or "split ergativity".

Ergative construction and nominative accusative construction in comparison

| Subj. Transit. verb | Subj. Intrans. verb | Obj. Transit. verb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ergative-absolute scheme | Ergative | Absolutely | Absolutely |

| Nominative accusative scheme | Nominative | Nominative | accusative |

Case formation

In Sumerian, the case is marked both on the noun (by suffixes ) and on the verb (by prefixes ), a phenomenon that is referred to as "double marking" in linguistics. In older research, the cases were defined solely on the basis of the nominal marking. This leads to a number of nine cases, of which the nouns of the person class form seven and those of the subject class form eight. The case markers (morphemes to mark the case) are identical in the singular and plural and are at the end of a noun phrase (see below), especially after the plural marker / -ene /.

The case marking by means of verbal preformatives is complicated by phenomena of contraction rules in conjunction with the effects of the syllable writing, which sometimes change the case markers very strongly. We cannot go into this in detail here (cf. Falkenstein 1978, Edzard 2003), especially since grammatical research into Sumerian is still quite in flux in this area.

According to a newer, u. a. The view taken by Zólyomi (cf. Zólyomi 2004 Weblink) is to use both the nominal and the verbal marking for the definition of the case in Sumerian. A case would then be any combination of one of the nominal markers with one of the verbal markers. According to this method of counting, the total number of Sumerian cases is significantly higher than 9.

The nominal case markings of the nouns lugal "König" and ĝeš "Baum" are as follows:

Example: Declination by case markers

| case | lugal | ĝeš | Function / meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolutely | lugal-Ø | ĝeš-Ø | Subject intrans. Verbs / you. Obj. Transit. Verbs |

| Ergative | lugal-e | (ĝeš-e) | Agent (subject) transitive verbs (almost exclusively PK) |

| Genitive | lugal-ak | ĝeš-ak | of the king / tree |

| Equative | lugal-gin | ĝeš-gin | like a king / tree |

| dative | lugal-ra | - | for the king (PK only) |

| Directive | - | ĝeš-e | towards the tree (only SK) |

| Terminative | lugal-še | ĝeš-še | towards the king / tree |

| Comitative | lugal-da | ĝeš-da | together with the king / tree |

| locative | - | ĝeš-a | by the tree (only SK) |

| ablative | - | ĝeš-ta | from the tree (only SK) |

| Plural | lugal-ene-ra | - | for the kings ( case marker after the plural marker ) |

The genitive attribute usually follows its rain (determinant), i.e.

- z. B. dumu-an-ak "the daughter ( dumu ) of the (sky god) An"

Enclitic possessive pronouns

Constructions like "my mother" are expressed in Sumerian by pronominal possessive enclitics . These enclitics read:

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | -ĝu | -to | (-a-) ni (PK), -bi (SK) |

| Plural | -me | -to-no-no | (-a) -no-ne |

Examples of possessive education

| Sumerian | German |

|---|---|

| ama-to | Your mother |

| dub-ba-ni | his / her writing board |

| ama-za (-k) | your mother (genitive) |

| dub-ba-ni-še | to his / her board |

The examples show that the possessive enclitonic comes before the case marker. -to , for example, before / a / to -za (Example 3).

Noun phrases

For all noun phrases (in the ancient Sumerians also nominal chains called) there is a well-defined position sequence. The order is:

- 1 phrase head + 2 attributive adjectives or participles + 3 numeralia + 4 genitive attributes + 5 relative clauses + 6 possessor +

- 7 plural markers + 8 appositions + 9 case markers

Of course, not all positions have to be occupied. Positions (2), (4), (5) and (8) can in turn be filled with complex phrases, so that multiple nestings and very complex constructions can result.

The individual positions of a noun phrase can be filled as follows:

| Item | designation | Casting options |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | head | Nouns, compound words , pronouns ; nominalized infinite verb forms |

| 2 | Adjectives / participles | Adjectives; infinite verb forms (used as an attribute) |

| 3 | Numeralia | Numerals; (if this position is occupied, position 7 must remain empty) |

| 4th | Genitive attributes | Noun phrases with genitive case marker (see above) |

| 5 | Relative clauses | finite sentences with subordinated (dependent) verb form |

| 6th | Possessor | possessive pronominal enclitics (see above) |

| 7th | Plural markers | Plural marker / -ene / (only if the head belongs to the PK and is not expanded by numbers) |

| 8th | Appositions | Noun phrases, which in turn can consist of positions 1 to 7 |

| 9 | Case marker | Case marker (see above "Case formation") |

In addition, a so-called "anticipatory genitive construction" is possible, in which the genitive phrase (position 4) precedes the remaining noun phrase but is repeated by a sumptive possessive pronoun (in position 6). An example of this is example 11 in the following overview.

Examples of Sumerian nominal chains

The digits in front of the constituents refer to the position in the chain. Note the nesting […].

| E.g. | Sumerian | Analysis / translation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | dumu saĝ An-ak | 1 daughter + 2 firstborn + 4 [1 to + 9 GEN] |

| "The first-born daughter of An" | ||

| 2 | ama-ani-ra | 1 mother + 6 POSS + 9 DAT |

| "For his mother" | ||

| 3 | e libir-eš | 1 house + 2 old + 9 TERM |

| "To the old house" | ||

| 4th | sipa anše-ak-ani | 1 shepherd + 4 [1 donkey + 9 GEN] + 6 POSS |

| "His shepherd of the donkey" = "his donkey shepherd" | ||

| 5 | Bad Lagaš ki -ak-a | 1 wall (s) + 4 [1 Lagaš location + 9 GEN] + 9 locomotive |

| "Within the walls of Lagaš" (plural not marked) | ||

| 6th | e inr̂u-aa | 1 house + 5 [he built + SUBORD (-a)] + 9 locomotive |

| "In the house that he built" | ||

| 7th | dumu d Enlil-ak-ak | 1 [1 son + 4 [1 God Enlil + 9 GEN]] + 9 GEN |

| "The son of (God) Enlil" | ||

| 8th | ama dumu zid-ani-ene-ak-ra | 1 mother + 4 [1 son + 2 true + 6 being + 7 PL + 9 GEN] + 9 DAT |

| "For the mother of his true (i.e. legitimate) sons" | ||

| 9 | ama dumu zid lugal-ak-ene-ak-ra | 1 mother + 4 [1 son + 2 true + 4 {1 king + 9 GEN} + 7 PL + 9 GEN] + 9 DAT |

| "For the mother of the true (= legitimate) sons of the king" | ||

| 10 | kaskal lu du-bi nu-gi-gi-ed-e | 1 path + 2 [1 man + 2 go (present participle) + 7 to be (related to the path)] + not ( nu- ) -return ( gi-gi ) -participle pres. / Fut. ( -ed ) + 9 DIR ( -e ) |

| "On a path from which someone who treads it will not return" | ||

| 11 | lugal-ak dumu-ani-ra | (anticipatory genitive construction) 4 [1 king + 9 GEN] + 1 son + 6 being (referring to the king) + 9 DAT |

| "For the son of the king" (with special emphasis on the "king") |

The examples show how complex nested noun strings can become. However, the regularity of the order makes it easier to interpret.

Noun phrase structure of other languages for comparison

| E.g | language | Noun phrase | analysis | translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sumerian | šeš-ĝu-ene-ra | Brother - POSS - PL - KASUS | for my brothers |

| 2 | Turkish | kardeş-ler-im-e | Brother - PL - POSS - KASUS | to my brothers |

| 3 | Mongolian | minu aqa nar major | POSS - brother - PL - KASUS | for my brothers |

| 4th | Hungarian | barát-ai-m-nak | Friend - PL - POSS - KASUS | for my friends |

| 5 | Finnish | talo-i-ssa-ni | House - PL - KASUS - POSS | in my homes |

| 6th | Burushaski | u-mi-tsaro-alar | POSS - mother - PL - KASUS | to their (3rd pl.) mothers |

| 7th | Basque | zahagi berri-etan | Hose - new - PL + KASUS | in the new tubes |

| 8th | Quechua | wawqi-y-kuna-paq | Brother - POSS - PL - KASUS | for my brothers |

These examples (No. 1–5 are from Edzard 2003) show that in agglutinating languages very different types of noun phrases are possible, as far as the order of their elements is concerned. In all of the mentioned and most of the other agglutinating languages, however, the order of the morphemes is subject to a fixed rule.

Independent personal pronouns

The independent personal pronoun in Sumerian is:

| Singular | Plural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | ĝe | I | ||

| 2nd person | ze | you | ||

| 3rd person | ane, ene | he she it | anene, enene | she PL.) |

The 1st and 2nd person plural are replaced by descriptive constructions. The independent personal pronoun has no ergative form, so it has the same form as the subject of transitive and intransitive verbs. This is one reason to speak of split ergativity in Sumerian.

Verbal morphology

The construction of the finite Sumerian verb is extremely complex because, in addition to the usual tense-subject markings, modal differentiations, references to the direction of the action, back references to the noun phrase and pronominal objects of the action must be accommodated in the verbal form. So one can speak of a polysynthetic verb formation in Sumerian . (The basic structure of the Sumerian verbal form is typologically very similar to the verb construction in Burushaski . The distribution of the functions of the pronominal suffixes and prefixes in transitive and intransitive verbs is almost identical. However, the Sumerian tense system is much simpler.)

Similar to the nominal chain (see above), the position of the respective morphemes is precisely defined. However, the practical analysis presents difficulties, since extensive contraction and assimilation rules and graphical features have to be observed. Many 'weak' formants such as / -e- / can simply be omitted.

The representation of the verbal morphology follows Zólyomi 2005 .

The 14 positions or slots of a Sumerian verbal form

Ten different prefixes can appear in front of the verbal base (verb stem form, see below), and after the verbal base up to three suffixes , so the Sumerian verb has - including the verbal base - 14 positions in which morphemes with a specific meaning can be used which then gives the overall meaning of the verb form. Such positions are also called “slots” - a term from the grammatical theory of tag memory . Of course, there is no specific Sumerian verb form in which all positions or slots are occupied. Some occupations are mutually exclusive.

The following table lists the slots in Sumerian verbal forms and explains them individually in the following sections, although the sequence of explanations is not identical to the sequence of slots for reasons of easier access.

The slots of the Sumerian verb

| slot | occupation |

|---|---|

| 1 | Negation, sequence or modal prefix |

| 2 | Coordination prefix / nga / |

| 3 | Ventiv prefix / mu / or / m / |

| 4th | Medium prefix / ba / |

| 5 | Pronominal adverbial prefix (with reference to the first occurring adverbial prefix) |

| 6th | Adverbial Prefix 1 - Dative / a / |

| 7th | Adverbial Prefix 2 - Comitive / da / |

| 8th | Adverbial prefix 3 - ablative / ta / or terminative / ši / |

| 9 | Adverbial prefix 4 - locative / ni / or directive / i / or / j / |

| 10 | Pronominal prefix |

| 11 | Verbal basis (see verbal classes ) |

| 12 | Present-future tense markers / ed / or / e / |

| 13 | Pronominal suffix |

| 14th | Subordinator / -a /: Nominalization of the verbal form |

The prosthetic prefix / i- / could be understood as “slot 0”, which is always used when there is otherwise only a single consonant as a prefix, the word begins with two consonants or when there is no other prefix, but the verb form should be finite.

Tense aspect

Sumerian has no absolute tenses , but a relative tense- aspect system. The "present future tense" (also called "imperfective") designates - relative to a reference point - actions that have not yet been completed at the same time or later, the "past tense" (also "perfect") expresses prematurely completed facts. State verbs only form the past tense.

The present-future and past tense tenses are distinguished in the indicative by different affixes in slots 10 and 13, the form of the verbal base (slot 11) and the present-future tense marker / -ed / in slot 12. Not all three labeling options appear in one form.

Verbal bases and verbal classes (slot 11)

The Sumerian verbs can be divided into four classes according to the form of their verbal bases (verb stem forms):

- Immutable verbs : these verbs have the same basis for the present tense and past tense (about 50% -70% of all verbs)

- Reduplicating verbs : The base is reduplicated in the present-future tense, various changes can occur.

- Expanding verbs : The present-future tense base is expanded by a consonant compared to the past tense base.

- Suppletive Verbs : The present future tense uses a completely different base than the simple past tense.

In addition, some verbs use a different base for plural agent or subject than for singular agent or subject. In principle, this leads to four "stem forms" of the verbal base, as the following examples make clear.

Examples of the verbal base

| verb | meaning | Prät Sg | Prät pl | Pres-Fut Sg | Pres-Fut pl | class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| šum | give | šum | šum | šum | šum | immutable |

| gu | eat | gu | gu | gu | gu | immutable |

| ge | to return | ge | ge | ge-ge | ge-ge | reduplicating |

| short | go inside | short | short | ku-ku | ku-ku | reduplicating |

| well | drink | well | well | na-na | na-na | reduplicating |

| e | go out | e | e | ed | ed | expanding |

| te | approach | te | te | teĝ | teĝ | expanding |

| ĝen / he (e) / du / su (b) | go | gene | he (e) | you | su (b) | suppletiv |

| dug / e | speak | dug | e | e | e | suppletiv |

| gub / šu (g) | stand | gub | šu (g) | gub | šu (g) | suppletiv |

| til / se | Life | til | se (sig) | suppletiv | ||

| uš / ug | to die | uš | ug | suppletiv |

By choosing different verb bases, two functions can be expressed:

- 1. The marking of the present-future tense versus the past tense.

- 2. the identification of the plural subject as opposed to the singular subject.

Pronominal suffixes in slot 13

There are two forms of pronominal suffixes that are used in slot 13 (row A and B), but they only differ in the 3rd person:

| 1st sg. | 2.sg. | 3.sg. | 1.pl. | 2.pl. | 3.pl. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row A | -en | -en | -e | -end up | -enzen | -ene |

| Row B | -en | -en | -O | -end up | -enzen | -it |

In the present tense future tense, the pronominal suffixes of row A designate the agent of a transitive verb and those of row B the subject of an intransitive verb, which (up to the end of the 3rd millennium usually) is preceded by / ed / in slot 12.

In the past tense only the pronominal suffixes of the series B are used. They mark the intransitive subject and the object of transitive verbs, as well as the plural agent.

Pronominal prefixes in slot 10

The pronominal prefixes in slot 10 denote the agent of the past tense (only the singular forms are used, see the conjugation scheme of the past tense) and the direct object in the present future tense. The forms 1st and 2nd person are not used in the plural:

| 1st sg. | 2.sg. | 3.Sg.PK | 3rd sg.SK | 3.pl. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| j, e (?) | j, e (?) | n | b or Ø | nne or b |

Present-future tense marker / -ed / in slot 12

If the verbal base has no special form for the present future tense, only / ed / in slot 12 differentiates the intransitive present future tense from the intransitive past tense.

Conjugation scheme of the present-future tense (imperfect)

This results in the following conjugation scheme for the present-future tense: (PF = present-future tense)

| slot | Slot 10 | Slot 11 | Slot 12 | Slot 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| function | object | Base | PF markers | Agent / intr. Subj. |

| transitive | pron. Pref. | PF base | pron. Suff. Row A | |

| intransitive | PF base | / ed / | pron. Suff. Row B |

Simple past conjugation scheme (perfect)

The pronominal prefixes of slot 13, row B (for forms see above) identify the subject of the intransitive verb and the direct object of the transitive verb in the past tense.

The agent of a transitive verb in the simple past is represented in the singular by the forms of the pronominal prefix in slot 10 (forms see above), in the plural also by the singular prefixes in slot 10 and additionally by the plural suffixes of slot 13, row B (forms see above). In this case (plural agent) a pronominal object cannot be marked because slot 13 is occupied. This results in the following conjugation scheme for the past tense:

| slot | Slot 10 | Slot 11 | Slot 13 |

|---|---|---|---|

| function | agent | Base | intr. subj./ obj. / plur. agent |

| intransitive | Pret base | Subject: pron. Suff. Row B | |

| transitive sg. agent | pron.Pref. | Pret base | Object: pron. Suff. Row B |

| transitive pl. agent | pron.Pref. so called | Pret base | Agent: pron. Suff. Row B pl. |

Summary of conjugations

The following table shows the conjugation of Sumerian verbs in the present-future tense (PF) and the past tense.

| Tense | Trans / Intrans | Slot 10 | Slot 11 | Slot 12 | Slot 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pron. Prefixes | Verbal base | PF markers | Pron. Suffixes | ||

| Pres-Fut | transitive | Object: pron. Pref. | PF base | Agent: pron. Suff. Row A | |

| intransitive | PF base | / ed / | Subject: pron. Suff. Row B | ||

| preterite | transitive Sg. | Agent: pron.Pref. | Pret base | Object: pron. Suff. Row B | |

| transitive pl. | Agent: pron.Pref. Sg. | Pret base | Agent: pron. Suff. Row B Pl. | ||

| intransitive | Pret base | Subject: pron. Suff. Row B |

Split Ergativity and Sumerian Verbal System

The present future tense actually uses a nominative-accusative system in the 1st and 2nd person, since the agent and intransitive subject are designated with the same pronominal suffixes in slot 13, while the prefixes of slot 10 identify the object. In the third person there is an ergative system with different affixes for agent and intransitive subject.

The past tense uses an ergative system throughout: intransitive subject and direct object use the same pronominal suffixes from row B in slot 13.

The adverbial prefixes in slots 6 to 9

In slots 6 to 9, adverbial prefixes can appear that provide adverbial supplements to the course of action.

| slot | Slot 6 | Slot 7 | Slot 8 A | Slot 8 B | Slot 9 A | Slot 9 B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| function | dative | Comitative | ablative | Terminative | locative | Directive |

| prefix | a | there (di) | ta (ra) | ši | ni | i / j |

Only one of the two variants can be implemented in slots 8 and 9. Before the locative prefix / ni /, the comitive prefix can become / di /, intervowels (between two vowels) the ablative prefix can be / ra /.

Pronominal prefixes in slot 5

The pronominal prefixes in slot 5 refer to the first adverbial prefix in slots 6–9 and are resumed by these. They are:

| person | 1st sg. | 2.sg. | 3.Sg.PK | 1.pl. | 2.pl. | 3.pl. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefixes | j (?) | ir, j, e | nn, n | me | ene | nne |

There are many exceptions and special cases when using these prefixes; in some cases, prefixes from slots 3 and 4 are used as replacements. Before the dative and directive prefixes, the 1st sg. a form of the Ventiv prefix / mu / (see slot 2 below) is used. As a replacement for the missing prefix of the 3rd sg. The medium prefix / ba / (see slot 4 below) is used for the subject class. In front of the prefixes / jr /, / nn /, / nne / in the initial position there is a prosthetic (preceding) / i- /.

Medium prefix / ba / in slot 4

The “medium prefix” / ba / in slot 4 expresses that the action directly affects the grammatical subject or his interests. Secondary is the function of / ba / as a replacement for the pronominal prefix in slot 5 in the 3rd sg. SK (last example).

Examples of the medium prefix / ba /

| Verb form | Analysis 1 | Analysis 2 | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| ba-úš | 4 ba - 11 uš - 13 Ø | MED-Die-3.sg.Subj | he dies |

| ba-hul | 4 ba - 11 hul - 13 Ø | MED-destroy-3sg.Subj | he was destroyed |

| ba-an-tuku | 4 ba - 10 n - 11 tuku - 13 Ø | MED-3.sg.Ag-haben-3sg.Obj | he took for himself |

| igi ba-ši-bar | igi-Ø 4 ba - 8 ši - 10 n - 11 bar - 13 Ø | Eye abs. 3.SA.Pr-TERM-3.Sg.Ag.-align-3Sg.Obj. | fixed his eye on something |

Ventiv prefix / mu / in slot 3

The "ventiv prefix" describes a movement of the action towards the place of the communicated facts or a verbal addition. Before the dative prefix (slot 6) or directive prefix (slot 9) it functions in the 1st so-called as a pronominal prefix (replacement for slot 5). Its forms are

- / m / before the vowel, before / b / and immediately before the verbal base (/ mb / is assimilated to / mm / and finally shortened to / m /);

- in all other cases it is / mu /, where the / u / can assimilate to the vowel of the following syllable.

Coordination prefix / nga / in slot 2

This prefix is prefixed to the last verbal form of a sibling chain of verbal forms and has the meaning “and also”, so it is a so-called sentence coordinator.

The modal prefixes in slot 1

Slot 1 contains the “negation prefix”, the “sequence prefix” or the actual “modal prefixes”.

The negation prefix (negative prefix) of indicative (and infinite) verbal forms is / nu- /, the / u / can be assimilated to the vowels of the following syllable. Before the syllables / ba / and / bi /, the negation prefix is / la- / or / li- /.

The sequence prefix / u- / expresses the temporality of the verbal form compared to the previously described actions ("and then ..."). / u / can assimilate to the vowel of the next syllable.

Seven prefixes in slot 1 describe the modality of the action, i.e. modify the neutral basic meaning of the verb form. The reality of the facts can be modified ("epistemic" modality: sure, likely, maybe, certainly not ...), or it can be described what should or should not be done ("deontic" modality).

Modal prefixes in slot 1

| prefix | use | semantics | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| ga- | deontic | positive, only 1st ps | I want / we want to do |

| Ha- | deontic | optional | must or should be done (wish that can be fulfilled) |

| epistemic | affirmative | is possible / sure that | |

| bara- | deontic | vetitive | must not be done |

| epistemic | strongly negative | is sure not | |

| na (n) - | deontic | weakly negative | shouldn't be done |

| epistemic | negative | is not possible that | |

| n / A- | epistemic | positive | Is it really like that |

| ša- | epistemic | positive | Is it really like that |

| nuš- | deontic | positive | should be done (impossible wish) |

Prosthetic / i- /

The prosthetic (preceding) prefix ì- always occurs when there would otherwise only be a single consonant as a prefix, the word began with two consonants or there is no prefix, but the verb form should be finite .

Examples of verb formation

In the verbal forms, the number of the slot is added for the individual components in the morpheme breakdown. (Slot 0 for the prosthetic / ì- /).

| E.g. | Spelling | Morpheme decomposition (with slots) / analysis | translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | lugal must | lugal-Ø mu (3) - ĝen (11) - Ø (13) König-ABS VENT – go.PRÄT – 3s.SBJ |

the king came |

| 2 | lugal-e bad ì-in-sè | lugal-e bad-Ø i (0) - n (10) - seg (11) - Ø (13) König-ERG Mauer-ABS PROTH-3s.AG-tear-down-3s.OBJ |

the king tore down the wall (s) |

| 3 | im-ta-sikil-e-ne | i (0) - m (3) - b (5) - ta (8) - b (10) - sikil (11) - e (12) - ene (13) PROTH-VENT-3.SK-ABL-3 .SK.OBJ-clean.PF-3p.PK |

they clean this with it |

| 4th | mu-ra-an-sum | mu (3) - jr (5) - a (6) - n (10) - sum (11) - Ø (13) VENT-2s-DAT-3.PK.AG-gab.PRÄT-3.OBJ |

he gave it to you |

| 5 | mu-na-ab-ús-e | mu (3) - n (5) - a (6) - b (10) - us (11) - e (12) - Ø (13) VENT-3.PK-DAT-3.PK.OBJ-impose- IPFV-3s.PK.AG |

he imposed it on him |

| 6th | zú-ĝu 10 ma-gig | zu-ĝu m (3) - Ø (5) - a (6) - gig (11) - Ø (13) Tooth-1s.POSS VENT-1s-DAT-illness.be.PRÄT-3.SBJ |

my tooth hurt me |

| 7th | ki-bi-šè ba-ni-in-ĝar | ki-bi-še ba (4) - ni (9) - n (10) - ĝar (11) - Ø (13) place-3.SK.POSS-TERM MED-LOC-3.PK.AG-places- 3.OBJ |

he put it in its place |

| 8th | nu-mu-ù-ta-zu | nu (1) - mu (3) - j (5) - ta (8) - Ø (10) - to (11) - Ø (13) NEG-VENT-2s-ABL-1s.AG -wissen.PRÄT- 3.OBJ |

I did not find out from you |

| 9 | ḫé-mu-ù-zu | ḫe (1) - mu (3) - j (10) - to (11) - Ø (13) PREK-VENT-2s.AG-Wissen.PRÄT-3.OBJ |

may you know! |

| 10 | ù-na-you 11 | u (1) - n (5) - a (6) - j (10) - dug (11) - Ø (13) SEQ-3s.PK-DAT-2s.AG-say.PRÄT-3.OBJ |

and then you told him this |

Explanation of the abbreviations:

| Abbr. | Explanation |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1st person |

| 2 | 2nd person |

| 3 | 3rd person |

| OJ | ablative |

| AGENS / AG | Subject in transitive sentences ( agent ) |

| DAT | dative |

| LOC | locative |

| MED | medium |

| NEG | negation |

| OBJ | direct object ( Patiens ) |

| p | Plural |

| PF | Present - future tense ( proper imperfect ; marû ) |

| PK | Person class (human) |

| POSS | possessive pronouns |

| PREK | Precarious |

| PROTH | prosthetic vowel / ì- / |

| PT | Past tense ( proper perfect ; ḫamṭu ) |

| s | Singular |

| SBJ | Subject in intransitive sentences |

| SEQ | sequential verb form (chronologically following the previous one) |

| SK | Factual class (non-human) |

| TERM | Terminative (case) |

| VENT | Ventiv |

Other forms

For the representation of further verbal forms (imperative, infinite forms), the use of other parts of speech (pronouns, numerals, conjunctions) and especially the Sumerian syntax, reference is made to the literature given.

literature

grammar

- Pascal Attinger: Eléments de linguistique sumérienne Editions Universitaires de Friborg. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1993, ISBN 3-525-53759-X .

- Dietz-Otto Edzard : A Sumerian Grammar . Brill, Leiden 2003, ISBN 90-04-12608-2 .

- Adam Falkenstein : The Sumerian . Brill, Leiden 1959, 1964.

- Adam Falkenstein: Grammar of the language of Gudea from Lagaš . Volume 1. Scripture and Forms; Volume 2. Syntax. Analecta Orientalia. 2nd Edition. Rome 28.1978, 29.1978.

- John L. Hayes: Sumerian. A manual of Sumerian grammar and texts . 2nd Edition. Undena Publications, Malibu CA 2000, ISBN 0-89003-197-5 .

- Bram Jagersma: A descriptive grammar of Sumerian. MS, Leiden 1999 (4th preliminary version).

- И.Т. Канева: Шумерский язык. Orientalia. Центр "Петербургское Востоковедение", Saint Petersburg 1996.

- Piotr Michalowski: Sumerian. In: The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages . Edited by Roger D. Woodard. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2004, ISBN 0-521-56256-2 .

- Arno Poebel : Basics of Sumerian grammar . Rostock 1923.

- Marie-Louise Thomsen: The Sumerian Language. An Introduction to its History and Grammatical Structure. Akademisk-Forlag, Copenhagen 1984, 2001, ISBN 87-500-3654-8 .

- Gábor Zólyomi: Genitive Constructions in Sumerian. In: Journal of Cuneiform Studies (JCS). The American Schools of Oriental Research . ASOR, Boston MA 48.1996, pp. 31-47. ISSN 0022-0256

- Gábor Zólyomi: Sumerian. In: Michael P. Streck (Ed.): Languages of the Old Orient . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2005 (basis for the short grammar presented here, in particular verbal morphology).

Dictionary

- John Alan Halloran: Sumerian Lexicon. A Dictionary Guide to the Ancient Sumerian Language. Logogram Publishing, Los Angeles 2006, ISBN 0-9786429-0-2 (previous versions of the print version also available on the Internet).

- Anton Deimel : Sumerisches Lexikon. Rome 1947.

Kinship

- John D. Bengtson: The Riddle of Sumerian: A Dene-Caucasic language? In: Mother Tongue , Gloucester MA 3.1997. ISSN 1087-0326

- Igor Michailowitsch Djakonow : External Connections of the Sumerian Language. In: Mother Tongue , Gloucester MA 3.1997. ISSN 1087-0326

- Igor Michailowitsch Djakonow: More on Possible Linguistic Connections of the Sumerians. In: Mother Tongue . Gloucester MA 5.1999. ISSN 1087-0326

- Ernst Kausen: The language families of the world . Part 1: Europe and Asia . Buske, Hamburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-87548-655-1 (Chapter 8)

Texts

- Edmond Sollberger, Jean-Robert Kupper: Inscriptions Royales Sumeriennes et Akkadiennes. In: Littératures anciennes du Proche-Orient. Les Editions du Cerf, Paris 5.1971. ISSN 0459-5831

- François Thureau-Dangin : The Sumerian and Akkadian royal inscriptions. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1907.

- Konrad Volk: A Sumerian Chrestomathy. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-447-06782-9 (Subsidia et Instrumenta Linguarum Orientis 5).

Web links

- Ernst Kausen: The Sumerian language . ( MS Word ; 182 kB) (Based on Edzard 2003 and especially on Zólyomi 2005; is the basis for this Wikipedia article.)

- Sumerian.org (English) with lots of information about the language and a PDF dictionary to download

- The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature . (English)

- The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary .

- The Unicode Standard 5.0, Section 14.10: Sumero-Akkadian (PDF; 326 kB)

- The Unicode Standard 5.0, Code Chart Cuneiform (PDF; 1.76 MB)

- Sumerian Lexicon - Electronic Search

Individual evidence

- ↑ John D. Bengtson : The Riddle of Sumerian: A Dene-Caucasic language? In: Mother Tongue , Gloucester MA 3.1997, pp. 63-74. ISSN 1087-0326

- ^ John D. Bengtson: Edward Sapir and the "Sino-Dene" Hypothesis Anthropol. Sci. 102 (3), 207-230, 1994 ( [1] on jstage.jst.go.jp) here p. 210

- ^ Gordon Whittaker: The Case for Euphratic. In: Bulletin of the Georgian National Academy of Sciences , Tbilisi 2008, 2 (3), pp. 156-168.