History of Elmina

The historically documented history of Elmina , today's small town in Ghana, spans more than five hundred years. It begins in 1482 with an agreement between the Portuguese navigator Diogo de Azambuja and the ruler of Elmina, called Caramansa by the Portuguese . This allowed the Portuguese to build the first European fortress in sub-Saharan Africa there. For the next 150 years or more, until the conquest by the Dutch in 1637, Elmina was the capital of the Portuguese bases on the Gold Coast, then for about 250 years the capital of the Dutch in West Africa . Since the capture of the lease contract for the two fortresses of Elmina by the Ashanti in 1701, the city has also had an outstanding importance for the Ashanti kingdom , i.e. the dominant regional power of the Gold Coast. Until the middle of the 19th century, Elmina was the most populous city on the Gold Coast , surpassing even Accra and Kumasi . The trade in gold , slaves and palm oil brought the city into direct contact with Europe, North America, Brazil and, through the recruitment of soldiers, also with Southeast Asia. Only with the takeover and extensive destruction of the reluctant city by the British in 1873 did Elmina lose its prominent position on the Gold Coast and became one of the coastal towns.

Elmina before the arrival of the Portuguese

Elmina today extends over two peninsulas, north and south of the Benya River . Settlement of the southern peninsula has been documented since at least 1000 AD. The settlement of the north peninsula, however, did not begin until modern times. Immediately before the arrival of the Portuguese at the end of the 15th century, the population was probably a few hundred people and Elmina was one of the larger settlements on what was later to be called the Gold Coast. In addition, 100 years before the arrival of the Portuguese, its inhabitants were trading in salt with the Akan peoples of the inland via the salt trade . Through these inland peoples, Elmina was connected - to a modest extent - to the great trade routes of West Africa and ultimately to the Trans-Saharan routes.

A village divided in two

Elmina was on the border of the two Fante states, Komenda and Fetu . Since the Portuguese also called the later Elmina “Aldea das duas Partes”, ie “Village of two parts (or parties)”, it has long been assumed that there was not one village here before the Portuguese arrived, but that there were two different fishing villages on both banks of the Benya lagoon , one of which belonged to Komenda (other name: Eguafo), the other to Fetu. Archaeological investigations in the 1990s, however, have clearly shown that there was no settlement north of the Benya before the arrival of the Portuguese. Both halves of the old Elmina were on the southern peninsula. One of the core settlements was located immediately to the west of today's Elmina Castle (and partly buried under the castle today), ie at the eastern end of the peninsula; the other part about 400 meters to the west, shortly before the present day Bantuma . The reason for the division of the village into two parts may have been that both parts were located at the elevated points of the peninsula and the area in between was occasionally flooded.

Later Dutch maps show that the areas in the west and northwest of Elmina were ruled by Eguafo / Komenda, while the areas in the east by Fetu. It cannot be ruled out that at the time of the arrival of the Portuguese the rulers of both states made claims on Elmina.

The unresolved question of the original Elmina's political affiliation has led to various speculations. For example, a sound similarity between the word "Caramansa", with which the "King of Elmina" was referred to in the first Portuguese reports, and the ruler title "Mansa" of the Mandinka people from the Sahel region, concluded that in Elmina before the Portuguese time Mandinka traders ruled. But apart from the sound similarity, there is no evidence of this. Since the term Caramansa no longer appears except in the earliest reports, it is more likely that the Mandinka term was used by an African translator he carried as a general term for "ruler".

Founding legend

According to a local legend, the founder of Elminas, Kwaa Amankwa, had Ashanti ancestors and came from Techiman in what is now the Brong-Ahafo region . The origin from Techiman coincides with the origin legend of the other Fante. What is unusual, however, is the emphasis on Ashanti descent, because Techiman was part of the Bono kingdom well into the 18th century . However, the legends agree that Kwaa Amankwa founded Elmina on the Benya River after discovering the place on a hunting trip. He named his settlement Anomansa , which translated means "inexhaustible supply of water".

The Portuguese Period: 1482–1637

In 1471 the Portuguese explored the coast of Elmina for the first time on behalf of the Lisbon merchant Fernão Gomes . Around 1482 they returned with a fleet of 10 caravels and two cargo ships under the command of Diogo de Azambuja . De Azambuja was commissioned to build a fortress on this site. On his ships he already carried material that was intended for the construction of a fortress according to European ideas.

The locals were interested in trading with the Portuguese and treated them friendly as long as the trade was carried out from the Portuguese ships. The plan to build a fortress near Elmina, however, met with rejection. The Portuguese negotiating partner was a local ruler named Kwamina Ansa, known as Caramansa by the Portuguese . A flowery speech “Caramansas” has been handed down, which boiled down to the fact that “friends who see each other occasionally remain better friends than if they became neighbors.” Despite this rejection, the Portuguese began building their fortresses and laid the foundation stone on January 21, 1482 for the later Fort São Jorge da Mina . According to Daaku, because of this resistance, they burned the place down. The Portuguese built a rectangular fortress on the elevated eastern end of the peninsula with towers on every corner and called it Castelo de São Jorge da Mina , i.e. fortress of St. George of Mina, now known as Elmina Castle. They called the place itself “El Mina”, meaning “The Mine”, referring to the place as the source of the gold they wanted to negotiate.

Diogo de Azambuja was appointed the first of 48 capitão-mayór , i.e. governors of Elmina . The governors of Elmina were later also governors of all later founded Portuguese possessions on the Gold Coast.

Meaning of Elminas

It was not by chance that Elmina became the site of the first European fortress on the Gold Coast. In favor of this place, there was already an African settlement of a noteworthy size as a prerequisite for trade and the use of local labor. The coast of what was later to become Ghana - in contrast to the inland - hardly had any larger towns at that time. A source from 1479 (Eustache de la Fosse) only mentions Elmina and Shama to the west as notable port locations. Even in this area it took three to four days in the 15th century before the news of the arrival of a ship had spread by drums and the traders had arrived there with their goods. In addition, the natural conditions were ideal: a rocky peninsula, located between the Benya lagoon and the ocean, easy to defend with the lagoon as a natural harbor. And finally there was the possibility of quarrying sandstone for the construction of the fortress on the peninsula - not a matter of course on the Gold Coast. In fact, as stated in some sources, De Azambuja did not carry all the material for the fortress construction with it, but only prefabricated stones for the foundations, archways and window openings. Most of the material for the fortress came from a quarry on the peninsula. The decisive factor for the Portuguese interest in the entire stretch of coast, however, was that from there the trade routes led inland to the sources of gold in the Ashanti area. Since salt had already been extracted in Elmina before the arrival of the Europeans and transported from there to the interior, a trade route into the interior already existed at the time of the arrival of the Portuguese.

The relationship between Portuguese and locals in Elmina

The Portuguese did not have unlimited power over the population of Elmina. Although the locals accepted it as a power that could settle disputes between Africans, this is probably also due to the role of the Portuguese as "neutral outsiders". The Portuguese were able to enforce a tax on fish and newly elected local African leaders were officially recognized by them. At the same time, however, they were dependent on the cooperation of the Africans. As a last resort in the event of dissatisfaction with European power, the Africans had the most effective means of leaving the city. Significant is a letter from the Portuguese king to the governor of Elmina in 1523. In it he expressed his concern that the people there would be treated too harshly, with the result that the city was depopulating. This is not in the interests of good trade relations, so people should rather be defended, protected and instructed. In fact, in 1529, by royal decree, Elmina opened the first school for local people to teach writing, reading and the Holy Scriptures.

The Portuguese (like the Dutch later) therefore banned the enslavement of natives in the Elmina area. A royal decree of 1615 named a radius of ten leguas (about 50 kilometers) around the city. Elmina was never a source of slaves, throughout their entire rule the Portuguese even imported slaves there and paid for the gold of the Ashanti with thousands of people from the so-called slave coast. The later importance of the city for the slave trade was based on its function as a transit station for displaced people from the 17th century.

In 1486 "Elmina" was granted the Portuguese town charter. In fact, according to individual sources, the city rights only related to the fortress there and not to the African settlement.

A Portuguese-based pidgin also developed very early in Elmina , which developed into the lingua franca of the entire Gold Coast and was not only used in contact between Africans and Europeans decades after the Portuguese were expelled.

From the very beginning of their presence here, the Portuguese tried to convert the locals to the Catholic faith and built several churches and chapels. The best known is a small chapel, built in 1503 on the hill above the city, on which the Dutch fortress Conradsburg was later to be built.

A stumbling block for the Portuguese in Elmina was the bureaucratic and inefficient organization of their rule, which was based on direct instructions from Lisbon. The post of governor was also commonly used as an opportunity for personal gain. At the same time, the "motherland" was often unable to guarantee adequate supplies for the garrison. In contrast to later colonial rulers, the Portuguese did not train craftsmen or other skilled workers among the locals. Even bricklayers to repair the fortress walls were regularly brought in from Portugal.

From 1514, however, there were joint military actions between the population of Elmina and the Portuguese. Warriors from Elmina also manned the ramparts of the fortress after the papal ban on selling firearms to Africans had been lifted in 1481 so that the Portuguese could arm their allies.

Creation of the state of Elmina

→ Main article: Elmina (state)

The former Fetu or Kommenda subordinate city of Elmina became an independent political unit through the alliance with the Portuguese in the first decades of the 16th century and later became the state of Elmina or Edina , which increasingly expanded its spatial sphere of influence.

Population in Portuguese times

There is no reliable information about the development of the city's population in Portuguese times. It can be assumed that the rapid growth of the urban population began back then. The adjacent view of Elmina from the year of the conquest by the Dutch shows a large African settlement west of the fortress. It is unclear whether it comprised more than several hundred residents. In any case, their growth is likely to have resulted from immigration, especially from the surrounding villages, rather than from natural birth growth. The European population in the city was small in Portuguese times. When Azambuja had the fortress of Sao Jorge da Mina built, he had 63 Europeans with him. At no time during the Portuguese period were there more Europeans living in the city and at the time of the conquest by the Dutch, the Portuguese garrison consisted of just 35 men. The commanders came mostly from the lower nobility of Portugal and many of the common men were sentenced to exile in Elmina for offenses. A contemporary listing lists only four women among Elmina's Europeans in 1529, all of them convicted. The group of so-called mulattos emerged from Portuguese-African connections . Their number can only be estimated, it is proven that after Elmina was captured by the Dutch, the mulattos received special permission to move with the Portuguese garrison to the island of São Tomé and 200 of them stayed in Elmina.

Cityscape in Portuguese time

The African settlement Elmina stretched westward directly from the walls of the fortress, limited by the natural conditions (location between ocean, lagoon and swampy lowland) and a settlement ban that the Portuguese imposed on the eastern part of the peninsula around their castle after the fortress was built left around. The fortress itself was built in the style of medieval castles: rectangular with towers at the four corners. Probably during the second half of the 16th century, the Portuguese erected a cannon-reinforced wall a few hundred meters west of the fortress to protect the city, which protected the entire settlement from the land side. The "urban area" of Elmina, enclosed by the wall and the sea or lagoon, thus comprised an area of around three hectares.

The report of a contemporary observer, de Marees, gives an indication of the hygienic conditions in the rapidly growing, densely built-up place, who wrote in 1602 that the city could be smelled at sea at a distance of 2.5 kilometers in wind from land.

The Dutch period 1637–1872

The Dutch had tried in vain to take the Portuguese fortress in Elmina five times: in 1596, 1603, 1606, 1615 and 1625. Each time they were repulsed with the support of the African inhabitants. Even several attempts to conquer the city after the walls of the fortress and a bastion were badly damaged by an earthquake in 1615 failed. In 1625 the Dutch tried to take Elmina again with a fleet of 15 ships under Jan Dirckszoon Lam . This attack, led with great superiority (around 1200 Dutch), failed with great losses due to the counterattack by his African allies organized by the Portuguese governor Francisco de Sotomaior .

In August 1637 the Dutch reappeared at Elmina with nine ships and around eight hundred soldiers. After only three days, they took the fort on August 29 with the support of around 1,000 to 1,400 armed Africans from Eguafo and Asebu . (see also main article Battle of Elmina 1637 )

The decisive factor in taking the fortress was a major strategic mistake by the Portuguese: on the north peninsula directly opposite the fortress, there was a hill from which it was possible to shoot cannons into the fortress. This hill had only been secured by an insignificant redoubt . With the conquest of the hill, the fortress could no longer be defended. The Dutch left a garrison of about 150 soldiers and strengthened the fortifications by building a fortress on the aforementioned hill, which they called Coenraadsburg .

The Dutch (more precisely: the Dutch West India Company ) immediately declared Elmina the capital of all their African possessions. The Governor General of Elmina therefore also carried the title of "Governor General of the Northern and Southern Coasts of Africa".

Relationship with the Dutch

As in the Portuguese period, the relationship between Europeans and Africans in Elmina under Dutch control was characterized by mutual dependence and the pursuit of mutual advantage in trade. The Dutch supported the Elminaer in conflicts with neighboring states as well as vice versa.

The relationship, which lasted 250 years, was not without conflicts. In 1739/140 there were violent clashes between the Elminaers and the Dutch when the then Governor General de Bordes refused to allow the fishermen from Elmina to pass through the Benya River into the ocean and in 1808 the residents of Elmina murdered Governor Hoogenboom in revenge for attacks by the Dutch .

During the Dutch period, Elmina's own political structures continued to develop and led to an increased self-confidence of the local rulers of the city towards the Dutch. It was not until the first half of the 18th century that the Dutch began to see the residents as their subjects, which they did not accept. The Dutch paid tribute (the Dutch called it "food money") for Elmina to the Kingdom of the Denkyra and later (see below) to the Kingdom of the Ashanti.

The Asafo companies

By the 18th century at the latest, the so-called Asafo societies were of decisive importance for the power structure in the city. The institution of the Asafo societies even preceded the emergence of a kingship (the office of Omanhene ). They had and still have both ritual and military tasks. Each Asafo society had a shrine and a flag. They also formed military units in the event of war. Such groups of men also existed in other Akan societies on the coast, but in Elmina they had a much stronger position in the political structure of the city or the state. The "king" (edenahene) of Elmina was determined by the Asafos and the Asafo leaders received a larger amount from the Dutch, also called "food money", than the king. The besonfo , a council of wealthy representatives of Elmina, which arose in the 19th century, also had its origins in the Asafo system.

In 1724 there were seven Asafo societies: Ankobia, Akim, Encodjo, Apendjafoe (Benyafoe, Benya, Wombir), Abesi, Allade (Adjadie, Abadie, Adadie) and Enyampa. The Asafos were each assigned to districts ("Kwartieren"). Three more were added in the 19th century. Two of these new Asafos consisted of refugees from Simbo and Eguafo who had settled in Elmina after the Fantekwar of 1810 . The 10th and last Asafo Society with the name Akrampa emerged from the slaves of the Dutch West India Company and their descendants, the so-called vrijburghers.

The kingship

The institution of a single ruler for the city and state of Elmina did not emerge until the 18th century. In 1732 a "King of Elmina" appeared for the first time in European reports as an obviously new institution. The Omanhene became the political, military and religious leader of Elmina. In contrast to the traditions of the other Akan peoples, this position was and is patrilineal , i.e. inherited along the male line. The Omanhene must belong to a certain Asafo (Enyampa Asafo) and come from either the Anona or the Nsona clan. The exact form of the royal office seems to have taken place only in the course of the 18th century. Contemporary Dutch sources speak of an "Oberkönig" and a "2." or "3rd King" in Elmina. There are indications that - even if traditional lists of kings try to give a different impression - the function of the Omanhene rotated for a while under the "sub-kings" and only gradually an exact succession was determined.

Rule in Elmina before kingship and Asafo

Knowledge of the political institutions in Elmina immediately after the city became independent from Fetu or Kommenda around 1500 to 1730 is largely limited to indications of what did not exist: There was no direct rule of the Portuguese or Dutch over the African city and no sole ruler. Portuguese sources from the 17th century speak of three "caboceers" or leaders of Elmina in three different parts of the city. and also that the people organize themselves as in a republic. Overriding disputes, however, were brought before the Portuguese and later the Dutch. De Corse quotes a Dutch governor general from 1639 about the residents of Elmina, who

"Bring all events to the (Dutch) governor-general, since they have no king, and they insist on their rights so much that they would rather take a life in danger than be deprived of their rights by a king."

Even if no reliable statements can be made about the exact internal organization of the city in the first two centuries after the construction of the fortress of Elmina, the picture emerges of an African community increasingly thrown together from different parts of the country, freed from direct supremacy with the European powers developed own ways of organizing their community in the fortress.

Population development in Dutch times

African

The population of Elmina rose sharply during the Dutch period. In the 18th century it should have been 12,000 to 16,000 people and in the 19th century it rose again to 18,000 to 20,000 people. Throughout the Dutch period, people from other parts of the coastal region of what was later to become Ghana asked for permission to settle here. In the 17th and 18th centuries it was people from Fetu, Eguafo, Akim and Denkyra, refugees from the wars between the Ashanti and Wassa , who came to Elmina, but also Ewe and Ga from eastern Ghana who did not belong to the Akan peoples. The place Bantoma, which borders directly on Elmina, still has a large proportion of Ewe today and it can be assumed that the Ewe formed part of the population of Elmina for a long time. Possibly also had Dioula - and Mande traders settled in the city. For the right of residence, the new citizens needed the consent of the Dutch and often they had to swear an oath of loyalty that included the promise of certain work for the Europeans. The slaves also contributed to this heterogeneous African population, who had been brought into the city, mostly from the "slave coast", since the Portuguese period, but only now made up a significant proportion of the city's population. It should be noted that the slaves in Akan society did not have a status without rights that could be compared to that of the American plantation slaves, rather they were incorporated into the Abusua , the matrilinear family association of the Akan.

Europeans

Europeans never made up a significant proportion of the city's population. In Portuguese times, their number never exceeded the 63 men who stayed there with Governor Azambuja after the fortress was built. At the time of the Dutch conquest, there were only 35 Europeans in the fortress. In the Dutch period, however, the number of Europeans increased. In the 17th century there were over 100 people and in the 18th century the majority of the up to 377 Europeans in Dutch service on the Gold Coast were stationed in Elmina. Often they came from workhouses , orphanages and prisons. However, the Europeans were by no means exclusively Dutch. Rather, Germans , French and Flemings also served here . From the middle of the 18th century the number of Europeans fell again when the West India Company increasingly took Africans and descendants of the Dutch into their service for reasons of cost. In the 19th century the number of Dutch people in Elmina fell again and at no time is it likely to have exceeded 20 people.

Tapojeires and Vrijburghers

As in the Portuguese period, there were connections among the Dutch between Dutch and African women from Elmina. Until the early 18th century, however, marriages between Europeans and Africans were rare and required the governor general's permission. There were significantly more children from illegitimate European-African connections in Elmina. The Dutch called these children Tapoeijers, probably because of their skin color after an Indian people. In 1700 there was a decree of the Governor General, which said that children from these connections either had to be taken with them by their Dutch fathers on their return to the Netherlands or the fathers had to pay a reasonable sum for the further "Christian upbringing" of their children within Elmina . In addition, a house was built in the city in which they were taught to write, basic economics, individual handicrafts and agriculture up to the age of 5 or 6.

Many of Elmina's Euro-Africans became successful traders. Probably the most important of them was Jan Nieser , who visited Europe several times and had direct trade contacts with European and American companies. His impressive house is shown opposite.

A part of this group achieved a special status and was called Vrijburghers , i.e. free citizens. They received the same rights as the Dutch and organized themselves into their own Asafo society (Akrampa). Her "Burgermeester" signed contracts with the Dutch independently and every Vrijburgher had the right to carry a sword. Many Euro-Africans worked in the lower echelons of the Dutch administration of the city and in the 19th century many of them sent their children to school in the Netherlands or England. Well-known Vrijburghers were Carel Hendrik Bartels, Jacob Huidecoper or Jacob Simon. It was unusual that many girls from this group were also sent to school in Europe. In the 19th century, the Vrijburgher settled mainly north of the Benyala lagoon in the area that was called "the garden" ("tuin") because this is also where the garden for the European Elminas was located. A district of its own developed here.

Development of the city in Dutch times

The cityscape of Elmina changed during the Dutch period. Furthermore, the city was characterized by a very irregular, chaotic floor plan and extremely dense settlement. Contemporary maps and representations that show a regular layout of the city are idealizations that contradict contemporary descriptions. However, a considerable number of stone houses were built early on by local craftsmen. Until the 19th century, the high number of stone houses such as the multi-storey stone house of the Elmina trader and “Vrijburgher” Johan Neizer shown above distinguished the cityscape of Elmina from that of all other cities on the Gold Coast.

The Dutch tried several times unsuccessfully to take urban planning measures, in particular to widen the streets in order to be able to better counter the constant threat of conflagrations. Documented is z. B. Such an attempt from 1837, when a fire destroyed 90 houses. The opportunity seemed favorable to pound new roads through the city and the Dutch had the planned routes marked out with bamboo sticks. However, women removed the marker sticks "while screaming outrageously". The Dutch then imprisoned the king and some elders. But even with this measure and the attempt to send 32 recruits into the city with rams to tear down the foundation walls of the burned down houses on the future route, they failed and the new roads were not built. The event sheds telling light on the real power the Dutch wielded over the city of Elmina outside the two forts.

In the 18th century the city began to expand to the northern peninsula, on which the Conraadsburg is located. As early as the 17th century, a drawbridge had been built over the lagoon, which encouraged the gradual settlement and gave access to the gardens of the West India Company below the Conraadsburg . The drawbridge was provided with guard houses at both ends to prevent foreign Africans from entering the city. Feinberg estimates the population of Elmina to be around 12,000 - 16,000 people in the first half of the 18th century.

Fortifications in the 19th century

In the last decades of their rule, the Dutch built several fortifications around the city, which, unlike the two large fortresses, were intended to ward off attacks from the inland. The first was Fort Beekestein, built in 1792 or 1793 about 300 meters west of Fort St. Jago (the Coonradsburg) on the Benya lagoon. It was a round redoubt , built of stone and clay on a hill, which offered a good overview of the area north of the settlement. When the Fante besieged the city in 1811, Fort Wakzaamheid ("vigilance") was built at the end of the south peninsula. Due to dilapidation, this facility was replaced between 1817 and 1829 by the Veerssche Schanz , which was named after the general director Jakobus de Veer . Further redoubts emerged in the 1820s with Fort Schomerus on the "Coebergh" (cow hill) and with the facility later called Fort Java on the "Cattoenbergh" (cotton hill), later Java Hill on the north peninsula. In 1869, shortly before the end of Dutch rule, Fort Nagtglas (named after the Dutch governor general Nagtglas ) was built at the northern end of the north peninsula.

"Black Dutch" in Elmina

In the 1830s, the Dutch found a new way to take advantage of their increasingly deficit Elmina estate after the abolition of the slave trade. They persuaded King Elminas to advertise the Dutch colonial army, the Koninklijk Nederlandsch-Indisch Leger , among his subjects . They enticed people with a secure income, the opportunity to see the world and the prospect of old-age insurance. Around 100 men, particularly from Afro-European families from Elminas and Accras , were recruited for the Dutch colonial army during this phase. The Dutch later signed a treaty with the King of the Ashanti to recruit additional recruits, who were brought to the Dutch East Indies , today's Indonesia , via Elmina . There they were called "Black Dutch" or in Javanese , the language of the main island Dutch in India, Belanda Hitam . Between 1831 and 1872 about 3,000 Africans came there and fought for the colonial rulers. At the end of their service, a smaller part of the Belanda Hitam returned to Elmina. There they were assigned parcels behind Fort Coonradsburg on a hill that is still called " Java Hill " today. The Belanda Hitam also appointed one of their own as the leader of their community, acting as a group for a time.

Today there is no longer any group in Elmina that can be identified as descendants of the Dutch colonial soldiers. The memory of this common Ghanaian-Indonesian history has been kept here for some time by its own Java Museum. Another legacy of Elmina's connection with Java is the art of batik , which began its triumphant advance over large parts of West Africa from Elmina.

Elmina and the Ashanti

Elmina and the Ashanti have been bound by an alliance of 200 years. In 1701 the Ashanti under Osei Tutu I defeated the army of the Denkyra Empire , to which the Dutch paid "food money" at that time, that is, "lease" or "regular gifts" depending on their point of view. The Ashanti captured the so-called " Elmina Note ", a document in which this lease was regulated. Even if there was disagreement between Ashanti and the Dutch about the nature of these payments, from then on the Dutch regularly paid two ounces of gold per month for Elmina to the new regional power Ashanti Empire. The Ashanti had direct access to the sea and trade with a European power (the Dutch) for the first time via Elmina. This resulted in a momentous alliance between the city of Elmina and the Dutch with the Ashanti, which soon faced a similar alliance between the Fanti (to which Elmina belonged linguistically and culturally) and the British. In 1810, 1828 and 1829 the Fanti besieged the city while the Ashanti refused to sign a peace treaty with the British and Fanti that did not include Elmina. The conflict over Elmina after the city was handed over to the British in 1871 (see below) was ultimately the reason for the Ashanti invasion of southern Afghanistan in 1873, which ended with the military defeat of the Ashanti and the Treaty of Fomena , in which the Ashanti made every claim had to do without southern Ghana.

With the alliance with the Ashanti, the city of Elmina decided on a special route that brought them into conflict with their entire linguistically and culturally related surrounding area and formed the background for the following events.

The Dutch withdraw and the city is destroyed

In 1850 the Dutch made serious efforts to get rid of their Elmina property, which had become unprofitable after the ban on the slave trade. The city's residents then sent a letter to the Dutch king protesting against the planned sale to the British and pointing out the 250-year relationship they had together. The plan was dropped - probably not because of this letter.

In 1867, the Dutch and the British finally decided to exchange fortresses on the Gold Coast to simplify the administration. The areas west of Elmina were to become Dutch, while those a few kilometers east were to become British. Although Elmina was to remain Dutch, the city was drawn into conflicts that ultimately ended in its destruction.

The plan met with fierce opposition from various previously British towns that were now to become Dutch. The background was the - well-founded - fear that through this change of ownership the areas west of Elmina would sooner or later fall to the Ashanti, the traditional allies of the Dutch and Elminas. This threat led to the unification of the previously divided Fanti states to form the "Council of Mankessim", the later Fanti Confederation . The Fanti formed a common army and moved to Elmina in March 1868 with the aim of driving out the Dutch. In April the Fanti army was strong enough to begin an effective siege of the city. In May of the same year, however, after a failed attack on the city, there were disagreements among the Fanti, which led to the siege being broken off. At the end of June, a peace treaty was signed between the Fanti Confederation and the city of Elmina. In the treaty, Elmina committed herself to neutrality in the event of a possible attack by the Fanti by the Ashanti. However, a blockade of the city, which was completely surrounded by the Fanti Confederation, remained in place in 1869 and 1870 and trade with the Ashanti came to a standstill. Attempts to get Elmina to join the Fanti Confederation failed. Elmina was the only place in the Fante settlement area that did not join the Confederation.

Elmina and the Dutch sent a formal request for help to the Asantehene, and on December 27, 1869, an Ashanti force under their warlord Atjempon arrived in Elmina. It soon became clear to the residents of Elmina as well as the Dutch that this Ashanti power was difficult to control and arbitrarily prevented any compromise with the Fanti and the British.

In July 1870, news finally reached Elmina that the Dutch had lost interest in their properties there due to the ongoing conflicts on the Gold Coast and were ready to hand over these properties, including Elmina, to the British. The Dutch governor of Elmina, Nagtglas, tried to convince the residents of Elmina to accept the surrender of their city to the British. The situation was complicated by the presence of an Ashanti army in the city, the leader of which the Dutch governor Nagtglas had arrested on short notice in April 1871. The ruling Asantehene Kofi Karikari clearly expressed his claim to fort and city Elmina in a letter to Nagtglas in 1870 and justified this claim with the Elmina note, which with the conquest of the kingdom of Denkyra by the Ashanti the rights to Fort Elmina to the Ashanti documented by the annual tribute paid by the Dutch to the Ashanti for the fort:

“The fortress in this square has paid annual tribute to my ancestors from time immemorial to this day, by virtue of the right of arms, since we Intim Gackidi, the king of Denkyra, for his ancestors paid £ 9,000 that the Dutch demanded for this right. "

Nagtglas contradicted this view of the Asantehene and in 1871 Kofi Karikari revoked his claim to Elmina - against the Dutch.

In 1872 the Dutch withdrew from the Gold Coast and their possessions were taken over by the British. However, the majority of the population of Elmina refused the British recognition of their rule. The Omanhene of Elmina, Kobina Gyan , told the British after they moved into Elmina Castle vacated by the Dutch:

“The castle previously belonged to the Dutch government and the people of Elmina were free men, they are not slaves who can be forced to do something. When the [British] governor [of Cape Coast] came to take over the castle, he did not consult me until he raised the British flag; if he recognized me as king, he would have done that ... The governor offered me a large sum of money as a bribe so that the handover would go smoothly and peacefully. I refused to accept the bribe, because if I had accepted the chiefs would have turned their backs on me afterwards and said that I had sold the land for money. "

In June 1873, the situation escalated when the Ashanti marched south to "regain" rule over various peoples of southern Afghanistan and specifically over Elmina. The Ashanti invasion was extremely successful until the middle of the year. An Ashanti army marched along the coast towards Elmina, but was stopped well before Elmina.

The British declared martial law on the city and exiled the Omanhens in their colony of Sierra Leone. After several ultimatums had expired, they began to bomb Elmina from warships on June 13, 1873 at 12 o'clock.

Since the population of the city got to safety in the "Castle" or in the surrounding area in good time, there were no fatalities. The Ashanti warriors tried to escape from the city, but 200 of them lost their lives in the fighting in the surrounding area, inland the British and Fanti fought back the Ashanti invasion together. The British made a distinction between "loyal" and "disloyal" districts or Asafos when they bombed Elmina. Four of the city's eight Asafos opposed the British, and four were considered "loyal". Disloyal, loyal to Kobena Gyan, the Omanhene of Elmina, and rejecting British claims, they viewed the core of the city west of St. George's Castle. This part was bombed and then plundered by allies of the British from the surrounding Fantestaaten, the parts north of the Benya are spared. In doing so, they finally destroyed the old town of Elmina on the peninsula west of the fort.

As remnants of the "Dutch times", several Dutch surnames can be found in Elmina to this day, as well as the Dutch cemetery and some Dutch inscriptions in Elmina Castle.

British times since 1873

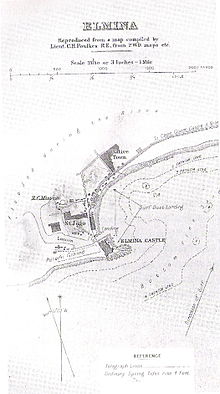

Following the bombing, the British razed the remains of the city to the ground, declared the resulting area a "parade ground" (see map) and forbade any new settlement on the Elmina peninsula, as they saw a security risk in a settlement in the immediate vicinity of the fort . It was years before Elmina returned to urban life. This new Elmina was - until today - no longer south, but north of the Benya.

With the British rule, Elmina not only finally lost its old importance for the entire region, the city also experienced actual colonization for the first time. Elmina was now part of the British Crown Colony, Gold Coast, which had been founded immediately before . The centers of the crown colony were Cape Coast and Accra , Elmina was a province. From 1880, however, the Catholic mission in Ghana, which was forbidden by the Dutch and for which the Basilica of St. Joseph as the country's oldest Catholic church, started again. At the beginning of the 20th century, the city had fewer than 4,000 inhabitants, about a quarter to a fifth of the population in the mid-19th century. A large part of the economically particularly active population did not return to the city, but settled in Kumasi and other places. In 1921 the city's port was also closed to trade. Nevertheless, the 1920s saw a limited economic boom in the city as capital flowed into the city from the gold and cocoa business and the colonial style of this time still characterizes some parts of Elmina.

Elmina since independence

Ghana's independence in 1957 did not fundamentally change this marginal location of Elmina. The population increased as did that of other Ghanaian cities. In 1960, 8,534 people lived in Elmina, ten years later there were a good 12,000 and today around 18,000 people live here. The city's history records the visit of Queen Elisabeth II to Elmina in 1960 as a major event. In 1979, the two fortresses of Elmina were declared a World Heritage Site and tourism has seen a significant boom since then.

At the beginning of the millennium, the "Elmina Heritage Project", a program for the restoration of the historical sites of Elmina, the two fortresses, the Asafoposten and several other historical buildings, started with considerable financial support from the European Union.

See also

- Elmina (State)

- History of Ghana

- Historic forts of Ghana

- Portuguese gold coast

- Dutch possessions on the Gold Coast

- List of governors of Ghana

literature

- René Baesjou (Ed.): An Asante Embassy on the Gold Coast. The Mission of Akyempon Yaw to Elmina, 1869-1872 (= African Social Research Documents. Vol. 11). Afrika-Studiencentrum et al., Leiden et al. 1979, ISBN 90-70110-25-3 .

- Adu Boahen: Politics in Ghana, 1800–1874. In: JFA Ajayi, Michael Crowder (Eds.): History of West Africa. Volume 2. Longman et al., London 1974, pp. 167-261.

- Christopher R. DeCorse: An archeology of Elmina. Africans and Europeans on the Gold Coast, 1400-1900. Smithsonian Institute Press, Washington DC et al. 2001, ISBN 1-56098-971-8 .

- Kwame Yeboa Daaku: Trade and Politics on the Gold Coast, 1600-1720. A Study of the African Reaction to European Trade. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1970.

- Albert van Dantzig: Forts and Castles of Ghana. Sedco Publishing Ltd, Accra 1980, ISBN 9964-72-010-6 (Reprinted edition. Ibid 1999).

- Harvey M. Feinberg: Africans and Europeans in West Africa. Elminans and Dutchmen on the Gold Coast During the Eighteenth Century (= Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. Vol. 79, 7). American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia PA 1989, ISBN 0-87169-797-1 .

- Harvey M. Feinberg: An Incident in Elmina-Dutch Relations. The Gold Coast (Ghana), 1739-1740. In: African Historical Studies. Vol. 3, No. 2, 1970, ISSN 0001-9992 , pp. 359-372.

- Nikolaus Hadeler: History of the Dutch colonies on the Gold Coast, with a special focus on trade. Trapp, Bonn 1904 (Bonn, Univ., Diss., 1904).

- JT Lever: Mulatto Influence on the Gold Coast in the Early Nineteenth Century: Jan Nieser of Elmina. In: African Historical Studies. Vol. 3, No. 2, 1970, pp. 253-261.

- Lennart Limberg: The Fanti Confederation 1868–1872. Göteborg 1974 (Göteborg, Univ., Diss., 1974).

- Larry W. Yarak: A West African Cosmopolis: Elmina (Ghana) in the Nineteenth Century. online ( Memento from March 13, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- Larry W. Yarak: The "Elmina Note:" Myth and Reality in Asante-Dutch Relations. In: History in Africa. Vol. 13, 1986, ISSN 0361-5413 , pp. 363-382.

Web links

- A West African Cosmopolis: Elmina (Ghana) in the Nineteenth Century ( Memento from March 13, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- District government website on the history of Elmina with legend

- On the history and population development of Elmina

- Current projects to preserve the historical heritage of Elmina (PDF file; 12 kB)

- About the spread of wax printing in West Africa and the role of Belanda Hitam and Elminas in it (PDF file; 4.47 MB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ DeCorse 18

- ↑ Yarak 1979

- ↑ DeCorse 32nd

- ↑ z. B. van Danzig: 9, but also others

- ↑ De Corse

- ↑ DeCorse 20

- ↑ DeCorse 49

- ↑ ghanadistricts on the history of Elmina ( Memento of the original from October 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Hadeler 12, other sources speak of six ships

- ↑ Daaku: 52

- ↑ Daaku 53

- ↑ De Corso: 18

- ↑ DeCorso 21

- ↑ DeCorse: 17

- ↑ DeCorse: 27

- ↑ DeCorse: 22

- ↑ DeCorse: 51, 168

- ↑ DeCorse: 51

- ↑ DeCorse 35

- ↑ DeCorse 49

- ↑ Van Danzig 1980: 4, van Danzig also shows in a drawing a moat on the land side, which cannot be found at De Corse

- ↑ DeCorse 51

- ↑ DeCorse: 31, 59

- ↑ Hadeler: 40ff

- ↑ Feinberg: 1989: 31

- ↑ Feinberg 1970

- ↑ http://www.africatoday.com/

- ↑ Feinberg 1970

- ↑ DeCorse: 58

- ↑ Yaruk

- ↑ DeCorse: 39f

- ↑ DeCorse: 40

- ↑ Feinberg 1989: 85, 95

- ↑ Feinberg 1989: 81-85

- ↑ De Corse: 33

- ↑ De Corse: 34ff

- ↑ De Corse: 35f

- ^ Van Dantzig: 60, Feinberg 1969: 123

- ↑ De Corse: 37

- ↑ De Corse: 37

- ↑ Yarak

- ↑ De Corse: 63

- ^ De Corse: 61

- ↑ Feinberg 1969: 117, De Corse: 54

- ↑ Feinberg: 35

- ↑ De Corse: 55/56. Some sources cite the names of these complexes as alternative names for the two great fortresses. That is not the case, traces of some of these redoubts can still be found today

- ↑ Yarak

- ↑ PDF at www.ifeas.uni-mainz.de

- ↑ Yarak 1986

- ↑ Boahen: 206

- ^ Limberg 23

- ↑ Limberg 25-30

- ↑ Limberg 48

- ^ Limberg 51

- ↑ Limberg 53

- ^ Limberg 60

- ^ W. Walton Claridge: A History of Gold Coast and Ashanti. From the earliest Times to the Commencement of the Twentieth Century. 2nd edition. Cass, London 1964, p. 603, quoted in Boahen: 232; Quote: The Fort of that place has from time immemorial paid annual tribute to my ancestors to the present time by rights of arms when we conquered Intim Gackidi, king of Denkyra'and that his ancestors had paid 9000 pound demanded by the Dutch for his right .

- ↑ Baesjou 1979, quoted from Yarak; Quote: This Castle belonged to the Dutch Government before, and the people of Elmina were free men; they are no slaves to compel them to do anything. When [the British] Governor [at Cape Coast] came to take this Castle he did not consult me before the English flag was hoisted; if he had considered me as king he would have done so… The Governor offered me as a bribe a large sum of money to let the transfer go on smoothly and peaceably. I refused the bribe because I had taken it chiefs would have turned round on me afterwards and said I sold the country for money.

- ↑ DeCorse 33

- ↑ DeCorse 57

- ↑ Yarak, cited Internet document

- ↑ De Corse

- ↑ DeCorse: 68

- ↑ Archive link ( Memento of the original from April 22, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.