Story of my escape

The story of my escape from the prisons of the Republic of Venice, which are called the lead chambers (original title: Histoire de ma fuite des prisons de la République de Venise qu'on appelle les Plombs ) is the title of an autobiographical work by the Venetian writer and adventurer Giacomo Casanova (1725–1798), who called himself Chevalier de Seingalt . The book was first published in French in 1788 in Leipzig .

content

Giacomo Casanova tells in the form of an adventure novel his escape from the prison of the Doge's Palace in Venice, the so-called “lead chambers” ( Piombi in Italian ).

The author describes his imprisonment, which began in the early morning hours of July 26, 1755 in the prison of the Doge's Palace, at that time a 'maximum security prison' for political prisoners of the Council of Ten and the Venetian State Inquisition . The reasons that led to the arrest by the Venetian police chief ( Capitan Grande or Messer Grande ) Matteo Varutti remain unexplained and are still the subject of controversial discussion today; Blasphemy , possession of forbidden books, forbidden contact with foreigners or Freemasonry are suspected .

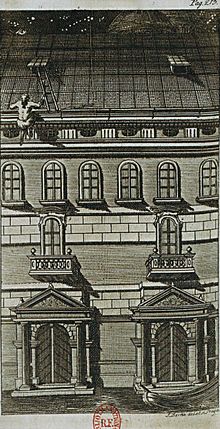

The lead chambers, a complex of seven cells in the east wing of the palace, were considered to be extremely escape-proof and were known as a prison with terrible detention conditions. The cells were located under the lead-roofed roof of the Doge's Palace. The lead plates in the unheated cells led to very low temperatures during the winter months and extreme heat in summer.

Casanova began planning his escape shortly after his arrest in July 1755. A first attempt failed because he was recently transferred to another cell. Only the second attempt was successful, on the night of October 31st to November 1st, 1756, together with a fellow prisoner, the Somaskan father Marino Balbi.

Casanova managed to get the necessary tools and climb out of his cell through a hole in the ceiling into the attic. He got to the roof and from there he lowered himself through a skylight back to another area of the palace. Camouflaged by the elegant clothes he was wearing at the time of his arrest, he left the palace through one of the main entrances, which the palace guards opened for him.

On board a gondola , Casanova and Balbi first reached the city of Mestre on the Italian mainland. From there Casanova continued his flight via Trento , Bozen and Munich to Paris , where he arrived in January 1757.

Impact history

News of his spectacular escape made Casanova a celebrity in pre-revolutionary Europe as early as the late 1750s, thirty years before the work was published, although many contemporaries had doubts about Casanova's version of the escape.

The following years took Casanova through Switzerland, Germany, France, Spain, England, Austria, the Netherlands, Poland, today's Czech Republic and Russia. He came into contact with important contemporaries from politics, art and science. He was only able to return to his hometown in 1774 after eighteen years of exile.

He did not finish writing his work until 1787, at Duchcov Castle (Dux) in Bohemia , today the Czech Republic . Today we are certain that Casanova's portrayal cannot be entirely fictitious; documents are known that confirm many details of his narrative. Through the detailed descriptions, the precisely described places and people, the story forms an important cultural-historical testimony of the 18th century.

The story was taken up again by Casanova in his " opus magnum ", the memoir (" Story of my life ") , his twelve-volume memoirs, which appeared posthumously from 1822 onwards.

literature

Text output

- Jacques Casanova de Seingalt: Histoire de ma fuite des prisons de la République de Venise qu'on appelle les Plombs . Ecrite a Dux en Boheme l'année 1787 . Schönfeld, Leipzig 1788

- Giacomo Girolamo Casanova: My escape from the state prisons in Venice, called the Piombi . Translation by Christian Andreas Behr, 1st edition, Gottlieb Heinrich Illgen, Gera and Leipzig 1797

- Giacomo Girolamo Casanova: My escape from the state prisons in Venice, called the Piombi . 2nd edition, Gottlieb Heinrich Illgen, Gera and Leipzig 1799

- Giacomo Casanova: My escape from the lead chambers of Venice. The story of my escape from the prison of the Republic of Venice, the so-called lead chambers, written down in Dux in Bohemia in 1787 , from the French by Ulrich Friedrich Müller and Kristian Wachinger, 2nd edition, CH Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3- 406-63330-0

Secondary literature

- Till Bastian: The All Saints Day Coup . In: Berliner Zeitung , November 4, 2006.

- Horst Albert Glaser (Ed.): The turn from the Enlightenment to Romanticism 1760-1820 . Volume 1, John Benjamin Publishing, Amsterdam 2001, ISBN 90-272-3447-7

- Marion M. Helmes (Ed.): Myths in Modernity and Postmodernism: World Interpretation and Mediation of Meaning . Weidler, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-925191-70-4

- Gerhard Jelinek : Affairs that moved the world . Ecowin, Salzburg 2011, pp. 97-104, ISBN 978-3-7110-0014-9

- Hermann Kesten : The lust for life. Boccaccio, Aretino. Casanova . Desch, Munich 1968

- Carina Lehnen: The praise of the seducer. About the mythization of the Casanova figure in German-language literature between 1899 and 1933 . Igel Verlag, Paderborn 1995, ISBN 3-89621-007-6

- Heinz von Sauter : The real Casanova . Engelhorn-Verlag, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-87203-020-5

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Casanova: My escape from the state prisons in Venice,… . 2nd edition, Illgen, Gera and Leipzig 1799, p. 11

- ↑ a b Jelinek, p. 97

- ↑ William Bolitho: Twelve Against Fate - The Story of Adventure . Müller and Kiepenheuer, Traunstein 1946, p. 78

- ^ Franz Blei: Portraits . Verlag Volk und Welt, Berlin 1986, p. 585, ISBN 3-353-00025-9

- ↑ Gabriele Cécile Weiher: Myths in Modernity and Postmodernism . Weidler Verlag, Berlin 1995, p. 130, ISBN 3-925191-70-4

- ↑ a b c Jelinek, p. 98

- ↑ Lehnen, p. 16

- ↑ Helmes, p. 130

- ↑ Glaser, p. 163

- ↑ From the memoirs of the Venetian Jacob Casanova de Seingalt, or his life, as he wrote it down at Dux in Böhmen , translated into German by Wilhelm von Schütz, Volume 4, Brockhaus, Leipzig 1823, pp. 365-543