Grigori Solomonowitsch Pomeranz

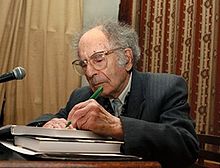

Grigori Solomonowitsch Pomeranz ( Russian Григо́рий Соломо́нович Помера́нц ; also Grigorij S. Pomeranc, born March 13, 1918 in Vilnius , Lithuania ; † February 16, 2013 in Moscow , Russia ) was a Russian philosopher and cultural theorist.

Life

While still at school, Pomeranz's family moved to Moscow . He studied Russian Linguistics and Literature at the Moscow Institute of Philosophy, Literature and History (IFLI). His candidacy dissertation on Fyodor Dostoyevsky was classified as anti-Marxist and he was denied a further academic career in the USSR . He then worked as a teacher at the Pedagogical University in Tula . During the Second World War, Pomeranz volunteered for military service. He was awarded the Order of the Red Star .

After the end of the war, Pomeranz was expelled from the Communist Party for "anti- party statements" and sentenced to five years in prison in 1949 for "anti-Soviet agitation". After Josef Stalin's death he was released as part of a general amnesty . In the next few years he worked as a village teacher in the Donets Basin and, after his return to Moscow, as a bibliographer at the Russian Academy of Sciences .

After the Hungarian uprising and the events surrounding Boris Pasternak , he became a dissident . As a dissident, he was not easily assigned to any specific dissident group. He was close to the democratic current of the Soviet dissidents. In 1965 he gave a lecture at the Moscow Institute of Philosophy, publicly speaking out against Stalinism and warning against returning to it. The lecture became one of the earliest documents in samizdat. He signed several human rights appeals, after which he was not allowed to defend his doctoral thesis on Zen Buddhism at the Academy's Institute for Oriental Studies.

Between 1976 and 1987 there was a publication ban for Pomeranz in the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, he wrote numerous essays and philosophical works, edited them in samizdat and tamizdat , and had an influence on the liberal intelligentsia of the 1960s and 1970s. The writings dealt with oriental studies and cultural studies as well as with religious-historical and philosophical topics such as the origins of the religions of India , Chinese philosophy and Meister Eckhart .

After perestroika , Pomeranz held irregular seminars and guest lectures at universities such as Moscow University . In the last year of his life he went blind, suffered from skin cancer and was restricted in his mobility.

He was married to the Russian poet Sinaida Mirkina .

Philosophical positions

Pomeranz was one of the first authors to take up the work of the art and literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin .

A recurring theme in Pomeranz's writings on cultural theory is the question of the possibility and necessity of dialogue between cultures. For Pomeranz, a condition for a fruitful cultural dialogue is the formation of so-called subecumens. The concept of the Sübokumenen is based on the terms "Kulturkreise" by Oswald Spengler , "Civilizations" by Arnold J. Toynbee and "Coalition of Cultures" by Claude Lévi-Strauss , but emphasizes the role of mutual influence. A subecumen exceeds nationally or ethnically distinct cultural characteristics and is defined by a common symbolic organization (language, literature, philosophy or religion) as well as a similar social structure (family, politics or economy). As such, Pomeranz identifies the Mediterranean , India and China . Several subecumens can be further connected by cultural characteristics that transcend ethnic or national characteristics, such as the Byzantine culture , which includes Slavic and Caucasian peoples. A theory of subecumens accordingly considers the process of knowledge production and transfer between such formations. The postmodern interpretation Pomeranz as a general crisis of Subökumenen.

Pomeranz had a dispute with Alexander Solzhenitsyn for several years . He criticized what he believed to be dogmatic Christian nationalism and positioned himself in the liberal camp of the Russian intelligentsia . Solzhenitsyn's idea of an irrevocable, global "evil" associated with communism contrasted Pomeranz with eastern thought traditions that do not have such a category of ontological evil.

Act

In 1970 Pomeranz took part in unofficial seminars in the apartment of the cyberneticist Valentin Turchin . Here he met Andrei Sakharov and impressed him with "his erudition, the breadth of his horizons and his" academics "in the best sense of the word." His essays were among the most popular samizdat works of the time.

Director Andrei Tarkovsky and composer Eduard Artemjew studied Pomeranz's lectures and his undefended doctoral thesis on Zen Buddhism while working on Stalker .

After perestroika , Pomeranz rarely commented on politics, and when he did, it was with sharp criticism. He was still respected by people who did not share his political views. The Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta called him the last moral authority in Russia. Outside of Russia, Pomeranz, unlike other dissidents, received little attention during his lifetime, although he was highly regarded among them.

Prices

- Bjørnson Prize from the Norwegian Academy for Literature and Freedom of Speech to Pomeranz and Mirkina “for their extensive contributions to strengthening freedom of speech in Russia”.

Works

Published abroad:

- Unpublished ( Неопубликованное ), Munich 1972.

- Dreams of the Earth ( Сны земли ), Paris 1984.

- Openness to the abyss. Experiments on Dostoyevsky ( Открытость бездне. Этюды о Достоевском ), New York 1989.

- The spiritual movement from the West. An Essay and Two Talks. Caux Books, Caux 2004, ISBN 2-88037-600-9 .

Published in Russia:

- Openness to the abyss. Encounters with Dostoevsky ( Открытость бездне. Встречи с Достоевским. ) Советский писатель, Moscow 1990, ISBN 5-265-01527-2 .

- Lectures on the philosophy of history ( Лекции по философии истории ), 1993.

- Themselves collect ( Собирание себя ) ЛИА "ДОК", 1993, ISBN 5-87710-008-4 .

- with Sinaida Mirkina: The great world religions ( Великие религии мира. ) Рипол, Moscow 1995, ISBN 5-87907-016-6 .

- Exit from the trance ( Выход из транса. ), Российская политическая энциклопедия, (1995) 2010, ISBN 978-5-8243-1319-2 .

- Notes of an ugly duckling ( Записки гадкого утенка. ), Московский рабочий, Moscow (1995) 2003, ISBN 5-8243-0430-0 .

- Paths of the Spirit and the Zigzag Course of History ( Дороги духа и зигзаги истории ), Российская политическая энциклопедия, 2008, ISBN 978-5-8243-0961-4 .

- In the shadow of the Babylonian tower ( В тени Вавилонской башни ), Центр гуманитарных инициатив, 2012, ISBN 978-5-98712-090-3 .

Published in Germany:

- Notes of an ugly duckling , from the Russian by Wilhelm von Timroth, Nostrum Verlag Mülheim a. d. Ruhr 2015, ISBN 978-3-9816465-1-1

literature

- Ferdinand JM Feldbrugge: Samizdat and political dissent in the Soviet Union. Sijthoff, Leyden 1975, ISBN 90-286-0175-9 .

- Tim Neshitov: Mass and power: Why a dying philosopher is considered the last moral authority of Russia (About Pomeranz) In: Süddeutsche Zeitung. November 16, 2012, page 12.

Web links

Interviews

- "Dissident for our times" , For A Change , April-May, 2001

- "Conversations in depth: Grigori Pomerants" , Herald of Europe No. 2, 2005

- "Preserving Depth. Interview with Grigory Pomerants" , Russia Profile , January 8, 2008

Article by Pomeranz

- "In God's Way" (PDF; 298 kB), Gregory Pomerants, Herald of Europe No. 7, 2010

- Список статей, «Журнальный Зал» - archive of articles from Pomeranz

- Записки гадкого утёнка - Pomeranz's autobiography Notes of an Ugly Duckling

- “Григорий Померанц: Жить без подлости” - the award speech at the Bjørnson Prize

Individual evidence

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20151002165925/http://tass.ru/en/archive/689810

- ↑ Grigory Pomerants: O roli nravstvennogo oblika lichnosti v zhizni istoricheskogo kollektiva. Igrunov.ru, December 3, 1965, accessed February 23, 2013 .

- ↑ Vladislav Zubok: Zhivago's Children: The Last Russian Intelligentsia . Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-674-03344-3 , pp. 263 .

- ↑ Russian Thinker Grigory Pomerants' Caux Lecture. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013 ; Retrieved February 22, 2013 .

- ^ In memory of Grigory Pomerants. hro.org, accessed February 24, 2013 .

- ↑ Grigory Solomonovitch Pomeranz. Pomeranz.ru, accessed on February 22, 2013 .

- ↑ s. Feldbrugge, 1975, pp. 154-155.

- ↑ a b c Д.М. Булынко, С.А. Радионова: Новейший философский словарь . Феникс, 2008, ISBN 978-5-222-13572-3 , ПОМЕРАНЦ Григорий Соломонович.

- ↑ Alexandar Mihailovic: Corporeal Words: Mikhail Bakhtin's Theology of Discourse . Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Il 1997, ISBN 978-0-8101-1459-3 , pp. 234 .

- ↑ Григорий Померанц: Выход из транса. Юрист, 1995, ISBN 5-7357-0028-5 , pp. 205-227, chapter: Теория субэкумен и проблема своеобразия стыковых культур

- ↑ Philip Boobbyer: Conscience, Dissent and Reform in Soviet Russia . Routledge, 2005, ISBN 978-0-415-33186-9 , pp. 125-126 .

- ↑ «Сон о справедливом возмездии (затянувшийся спор с Александром Солженицыным , 1990, Григорий Померанц,", "# 11" Вомеранц, # 11

- ↑ Andrej Sacharov, Annelore Nitschke u. a. (Ex.): My life . Piper, Munich et al. 1991, ISBN 3-492-03259-1 , p. 338 .

- ↑ Lyudmila Alexeyeva, John Glad: Soviet Dissent: Contemporary Movements for National, Religious, and Human Rights . Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, Conn. 1987, ISBN 0-8195-6176-2 , pp. 327 .

- ↑ Maya Turovskaya: 7½, ili filmy Andreia Tarkovskovo . Iskusstvo, Moscow 1991, ISBN 5-210-00279-9 , Eduard Artemyev talks to Maya Turovskaya.

- ↑ Oleksiy-Nestor Naumenko, Eduard Artem'ev: Eduard Artemyev. Kak poyut derev'ya. In: Iskusstvo Kino. April 2007, accessed January 27, 2014 (Volume 4).

- ↑ a b Tim Neshitov: About the Russian philosopher Grigorij Pomeranz. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung. Nov 16, 2012.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pomeranz, Grigori Solomonowitsch |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Pomeranc, Grigorij Solomonovič (scientific transliteration); Померанц, Григорий Соломонович (Russian spelling) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian philosopher and cultural theorist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 13, 1918 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vilnius |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 16, 2013 |

| Place of death | Moscow |