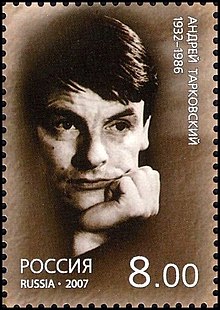

Andrei Arsenyevich Tarkovsky

Andrei Arsenjewitsch Tarkovsky ( Russian Андрей Арсеньевич Тарковский , scientific transliteration Andrej Arsen'evič Tarkovskij ; born April 4, 1932 in Savrashye ( Russian Завражье ), Soviet Union ; † December 29, 1986 in Paris , France ) was a Soviet film maker .

life and work

Andrei Tarkowski was born in the village of Savrashye in what is now Kostroma Oblast in northwestern Russia, the son of the famous poet and translator Arseni Tarkowski and Maria Ivanovna Vishniakova. His grandfather, Aleksander Tarkovsky, was a Polish nobleman who worked in banking in Russia. After his parents separated in 1936, Tarkovsky grew up with his mother and grandmother. During the Second World War the family lived in the small town of Yuryevets , and in 1944 they moved back to Moscow. His artistic talent made itself felt at an early age, which was encouraged by his mother. In the 1950s he first studied music , painting , sculpture , oriental studies and geology , before beginning to study at the WGIK film school in Moscow in 1954 , where director Michail Romm was his teacher.

Soviet Union 1961 to 1983

Tarkowski graduated from WIGK in 1961. His thesis was the film The Road Roller and the Violin , which already showed its idiosyncrasy, but which he himself never counted among his work.

His first full-fledged feature film Ivan's Childhood was released in 1962 and made Tarkovsky famous overnight. The work is based on the story Iwan by Vladimir Ossipowitsch Bogomolow , a Russian-Soviet prose writer, and describes the war experiences of a twelve-year-old boy. The film was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice International Film Festival in 1962 and received the Golden Gate Award for best director at the San Francisco Film Festival .

In 1964, the shooting of Andrei Rublev began , the film could only be shown in a heavily abridged and censored version at the Cannes Film Festival in 1969 after severe criticism from the state; it was only released in the Soviet Union in 1973.

In 1972, Solaris was released , a film adaptation of the science fiction novel of the same name by Stanislaw Lem . The 1975 film Der Spiegel has strong autobiographical traits. Between 1974 and 1979 Stalker was created as a free adaptation of the science fiction novel Picnic on the wayside by Boris Strugatzki and Arkadi Strugatzki . Stalker is the last film produced by Tarkovsky in the Soviet Union.

Exile 1983 to 1986

Tarkovsky was in poor health and had suffered several heart attacks. He left the Soviet Union in 1983 and applied for asylum in Italy. Nostalghia was created here in 1983 . At the 1983 Cannes Film Festival , Nostalghia was awarded the Ecumenical Jury Prize and the FIPRESCI Prize. Tarkowski shared the directing award with Robert Bresson , the laudatory speech for both directors was given by Orson Welles .

Tarkowski did not return to the Soviet Union, which ultimately broke up his family. He then stayed in Paris, London and Berlin, where he received a scholarship from the German Academic Exchange Service. In 1985 he published the book Die versiegelte Zeit , in which he presented his main thoughts on the aesthetics and poetics of film.

His last film, Sacrifice , was made in Sweden in 1985 and won the jury award at the Cannes Film Festival. When the Chernobyl reactor disaster struck at that time , it was for Tarkovsky the realization of his worst nightmares. At this point he was already seriously ill and his treatment in Paris came too late. He could no longer implement his plan to shoot the film Hoffmanniana about the last days in the life of ETA Hoffmann in Berlin.

Tarkowski died of cancer on December 29, 1986 in Paris at the age of 54. He rests in the Russian cemetery in Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois in the Essonne ( Île-de-France ) department near Paris next to his long-time assistant and second wife Larissa Tarkowskaja .

After his death, Larissa Tarkovskaya dedicated herself to the preservation of Tarkovsky's legacy, actively participating in the establishment of the Institut international Andreï-Tarkovski in Paris and the publication of his writings. Shortly after she had completed the biography published by Calmann-Lévy under the title “Andreï Tarkowski” , Larissa Tarkowski died on January 19, 1998 at the age of 60 in Neuilly-sur-Seine near Paris.

Tarkowski's cinematic form of expression

During his time at the film school, Tarkowski was fascinated by the works of Buñuel , Bergman , Fellini and the neorealism of Italian and French post-war cinema. In addition to autobiographical elements (poems by his father are recited in some of his films), it is above all the constantly recurring special pictorial motifs that form Tarkovsky's specific style.

Tarkowski's films are characterized by a very calm, often almost static imagery. The focus is not on a specific course of action; rather, images should create moods.

Tarkowski writes in Die versiegelte Zeit that his films should “not communicate with the viewer via clearly retellable content”, but “reanimate basic psychological states”, which are generally valid and can therefore be understood by the recipient if the recipient is emotionally open. The “logic of the poetic” is “closer to him than the traditional dramaturgy” and pure “chain of events”, since this is based on a “banalization of the complex reality of life”. Only the “poetic connection causes great emotionality and activates the viewer”.

Tarkowski was fascinated by "the rust of things, the magic of the old, the seal / the patina of time", which is also reflected in the imagery of his films. B. the (industrial) ruins in Stalker or the remains of the Gothic religious building in Nostalghia . With these elements, impressive images of nature such as B. the birch forest in Ivan's childhood , the meadows and forests of the zone in Stalker or the repeatedly appearing motif of water.

Nevertheless, these cinematic images are not to be understood as concrete symbols. Tarkowski himself writes: “Nothing is symbolized in any of my films. [...] The symbol is only a true symbol if it is inexhaustible and limitless in its meaning. "

The soundtrack for many of his films was composed by Eduard Artemjew and set to music using the first Soviet synthesizer . Classical, mostly sacred works, especially by Johann Sebastian Bach, occupy a central position.

Reception and effect

Tarkovsky was famous abroad, but he was denied official recognition in his home country. Tarkowski's films could only be published in the Soviet Union against strong opposition from the authorities. Most of them, however, received regular awards at international film festivals, also against the protests of the official Soviet representatives.

Thanks to his enthusiasm for experimentation and the haunted nature of his films, Tarkowski earned great recognition among film buffs and filmmakers around the world. Ingmar Bergman said of him: "Tarkowski is the most important to me because he has found a language that corresponds to the essence of the film: life as a dream."

In 1988 the asteroid (3345) Tarkovskij, discovered on December 23, 1982, was named after him.

In 2002 the Center Pompidou honored Tarkowski, who would have celebrated his seventieth birthday that year, with a major retrospective. On the twentieth anniversary of his death in 2006, the City of Paris and the Andreï-Tarkovski Institute had a plaque put up on the house in rue Puvis-de-Chavannes (N ° 10) where Tarkovsky last lived.

The 2009 film Antichrist by Danish director Lars von Trier is dedicated to him.

Works

Short and documentary films

- 1958: Ubiizy (The Killer) based on the short story of the same name by Ernest Hemingway , black and white film, as a student

- 1959: Sewodnja uwol'nenija ne budet (Today there is no evening), black and white film, as a student

- 1961: Katok i skripka ( The road roller and the violin ); Short, diploma and children's film, color

- 1982: Tempo di Viaggio (Italian Tour), documentary for Italian television about finding locations for Nostalghia, together with Tonino Guerra

Feature films

- 1962: Iwanowo detstwo ( Iwan's childhood ), black and white film

- 1964–1966: Andrej Rublev , color and black and white film

- 1972: Soljaris ( Solaris ), based on the novel Solaris by Stanisław Lem

- 1974/75: Serkalo ( Der Spiegel ), color and black and white film

- 1979: Beregis, zmej! (Beware, snakes!) (Script only)

- 1979: Stalker , color and black-and-white film, based on a section from the Strugazki brothers' Picnic by the wayside and based on their screenplay, Die Wunschmaschine, derived from the novel

- 1983: Nostalghia , color and black and white film

- 1985/86: Offret (Sacrificatio; sacrifice )

- In addition, collaboration on films by other authors and directors

Theater and opera

- 1977: Hamlet , Lenin Komosomol Theater Moscow (director)

- 1983: Boris Godunow , Covent Garden Opera London (director)

Radio plays

- 1964: Polny poworot krugom ( Full power back!) Based on the story Turnabout by William Faulkner , music: Vjatscheslav Ovtschinnikov, production: Gostelradio Moscow, German version translated from Russian by Hans-Joachim Schlegel, SWF 1990

- 2004: Hoffmanniana. Based on a film scenario by Andrej Tarkowskij (sic!) About the last days in the life of E. T. A. Hoffmann , director: Kai Grehn , RBB / SWR

Fonts

- The sealed time. Thoughts on art, on the aesthetics and poetics of film. Translated from the Russian by Hans-Joachim Schlegel . Ullstein, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-550-06393-8 , revised new edition: Alexander, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-89581-200-2 .

- The sealed time - Ivan's childhood as an offering. Cahiers du cinéma, Paris 1989

- The victim. With film images by Sven Nykvist . Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 1987 (Tarkovskij Edition, Volume 1)

- Hoffmanniana. Scenario for an unrealized film. Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 1987 (Tarkovskij Edition, Volume 2)

- Martyrolog. Diaries 1970 - 1986. Limes, Berlin 1989 a. Cahiers du cinéma, Paris 1993

- Martyrolog II. Diaries 1981 - 1986. Limes, Berlin 1991

- Andrei Rublev. The Novelle. Limes, Berlin 1992

- The mirror. Film novella, work diaries and materials for the making of the film. Limes, Berlin 1993

- Photographs. Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 2004

- Andrej Tarkovskij - Life and Work: Films, Writings, Stills & Polaroids Edited by Andrej A. Tarkovskij jun., Hans-Joachim Schlegel, Lothar Schirmer. Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 2012 ISBN 978-3-8296-0587-8 .

- Make the incomprehensible visible. - 6 masterpieces by Andrei Tarkowski: Films and accompanying book edition trigon-film, Ennetbaden 2014

Literature on Tarkovsky

- Andrej Tarkovskij - Life and Work: Films, Writings, Stills & Polaroids . Edited by Andrej Tarkovskij jun., Hans-Joachim Schlegel and Lothar Schirmer. Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-8296-0587-8

- Tarkovsky - Films, Stills, Polaroids & Writings. Edited by Andrey A. Tarkovsky, Hans-Joachim Schlegel and Lothar Schirmer. Thames & Hudson, London 2012, ISBN 978-0-500-51664-5 .

- Larissa Tarkovski (with the assistance of Luba Jurgenson): Andreï Tarkowski. Calmann-Lévy, Paris 1998

- Andrei Tarkovsky. With contributions by Wolfgang Jacobsen a. a., Hanser, Munich 1987

- Julia Selg: Andrej Tarkovskij and the presence of the old masters, art and culture in the film Nostalghia. Ita Wegman Verlag, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-9523425-9-6 .

- Marina Tarkovskaya: Sliver of the mirror. The family of Andrei Tarkovsky. edition ebersbach, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-934703-59-3 .

- Antoine de Baecque: Andrei Tarkowski. Cahiers du cinéma, Paris 1989

- Maja Turovskaya : Andrei Tarkovsky. Film as poetry, poetry as film. Keil Verlag, Bonn 1981

- Timo Hoyer : Film work - dream work. Andrei Tarkovsky and his film "Der Spiegel" ("Serkalo") . In: R. Onion / A. Mahler-Bungers (Ed.): Projection and Reality. The unconscious message of the film . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, pp. 85–110. ISBN 3-525-45179-2 .

- Hans-Dieter Jünger: Art of Time and Remembrance. Andrei Tarkovsky's concept of the film. Ed. Tertium, Ostfildern 1995, ISBN 3-930717-12-3 .

- Marius Schmatloch: Andrei Tarkovsky's films from a philosophical perspective. Gardez! Verlag, St. Augustin 2003, ISBN 3-89796-050-8 .

- Hans-Joachim Schlegel: Inner Sound Worlds. On Andrej Tarkovsky's sound and music concept . In: Hartmut Krones (Ed.): Stage, Film, Space and Time in the Music of the 20th Century . Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2003 ISBN 3-205-77206-7 .

- Dietrich Sagt: The mirror as a cinematograph after Andrej Tarkowskij. Dissertation, urn : nbn: de: kobv: 11-10036006, approx. 0.9 MB, (PDF), Philosophical Faculty III, Humboldt University, Berlin 2004; Full text at the German National Library

- Nina Noeske: Music and Imagination. JS Bach in Tarkovskijs Solaris . In: Film music. Contributions to their theory and mediation , ed. by Knut Holtsträter, Oliver Huck and Victoria Piel, Hildesheim, Zurich, New York, Olms, 2008, pp. 25–42, ISBN 978-3-487-13640-0 .

- Florian Sprenger: "1 + 1 = 1 - moving elements in the work of Andreij Tarkowskij." In: Birgit Leitner, Lorenz Engell (ed.) Philosophy of Film. Verlag der Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, Weimar 2007, pp. 128–141

- Hans-Joachim Schlegel: film image and icon. Consequences of the Byzantine understanding of images in Russian and Soviet film . In: Peter Hasenberg , Reinhold Zwick, Gerhard Larcher (eds.): Time - Image - Theology. Schüren, Marburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-89472-674-4 .

- Layla Alexander-Garrett: Andrei Tarkovsky: A Photographic Chronicle of the Making of The Sacrifice , Cygnnet, 2012, ISBN 978-0-9570416-0-8 .

Films about Tarkovsky

- 1987: Donatella Baglivo: Andrei Tarkovsky (also broadcast under the title Tarkovsky's Cinema ). Documentary, UK 1987, 53 min

- 1988: Ebbo Demant : In search of lost time. Andrei Tarkovsky's exile and death. Documentary, Germany, 130 minutes

- 2000: Chris Marker : Cinéma, de notre temps. Une journée d'Andrei Arsenevitch. France, 55 minutes

Other work on Tarkowski

- Various Artists: In Memoriam Tarkovsky. CD, Insofar Vapor Bulk, 2002, with compositions by Christian Renou, Roger Doyle, Michael Prime, Stanislav Kreitchi

- Francois Couturier: Nostalghia. Song for Tarkovsky. CD, ECM, 2006

Web links

- Andrei Tarkovsky in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Literature by and about Andrei Arsenjewitsch Tarkowski in the catalog of the German National Library

- About Andrej Tarkowski and his films

- Andrei Tarkovsky Information Site (English)

- Andrei Tarkowski at Rotten Tomatoes (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Lexicon of international film 1999/2000 (CD-ROM) , Systema Verlag Munich 1999, quoted from Andrej Tarkowskij - Ein Philosopher des Kinos , Icestorm Media 2005

- ^ Festival de Cannes: Nostalghia . In: festival-cannes.com . Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- ^ Lexicon of international film 1999/2000 (CD-ROM) , Systema Verlag Munich 1999, quoted from Andrej Tarkowskij - Ein Philosopher des Kinos , Icestorm Media 2005

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Schlegel: The unity of visible and invisible reality , epilogue to the German edition of Die versiegelte Zeit , Alexanderverlag, Berlin 2009

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Schlegel: The unity of visible and invisible reality , epilogue to the German edition of Die versiegelte Zeit , Alexanderverlag, Berlin 2009

- ↑ Minor Planet Circ. 13176

- ↑ John Gianvito (Ed.): Andrei Tarkovsky - Interviews , University Press of Mississippi, Jackson 2006

- ^ Lexicon of international film 1999/2000 (CD-ROM) , Systema Verlag Munich 1999, quoted from Andrej Tarkowskij - Ein Philosopher des Kinos , Icestorm Media 2005

- ↑ The film in the IMDb

- ↑ The film in the IMDb

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tarkovsky, Andrei Arsenyevich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Tarkovskij, Andrej Arsen'evič; Тарковский, Андрей Арсеньевич (Russian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | soviet director |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 4, 1932 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Zavrashye , Ivanovo Oblast, Soviet Union |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 29, 1986 |

| Place of death | Paris , France |