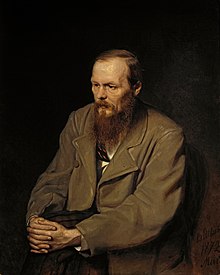

Fyodor Michailowitsch Dostoevsky

Fyodor Dostoyevsky (even Dostoyevsky , [ fʲodər mʲɪxajləvʲɪtɕ dəstʌjɛfskʲɪj ], scientific transliteration Fedor Mihajlovic Dostoevsky * 11. November 1821 in Moscow ; † 9. February 1881 in Saint Petersburg ) is one of the most important Russian writer . His writing career began in 1844; the major works, including Guilt and Atonement , The Idiot , The Demons and The Karamazov brothers , however, did not emerge until the 1860s and 1870s. Dostoevsky wrote nine novels, numerous short stories and short stories and an extensive corpus of non-fictional texts. The literary work describes the political, social and spiritual conditions at the time of the Russian Empire , which was fundamentally in transition in the 19th century. Dostoevsky was a seismograph of the conflicts that humans got into with the dawn of modernity . The central subject of his works was the human soul, whose impulses, compulsions and liberations he traced through the means of literature; Dostoevsky is considered to be one of the most outstanding psychologists in world literature. Almost all of his novels appeared in the form of feuilleton novelsand therefore shows the short arcs of tension typical of this genre, which makes it easily accessible even to inexperienced readers despite its many layers and complexity. His books have been translated into more than 170 languages.

In the second half of the 1840s Dostoevsky was close to early socialism and took part in meetings of the revolutionary Petraschewski circle . This led to his arrest in 1849, sentenced first to death and then - after the sentence was changed - to imprisonment and subsequent military service in Siberia . After his release in 1859, he began to restore his reputation as a writer, first with minor work and then with the notes from a house of the dead . With his brother Michail he founded two magazines ( Wremja and Epocha ). The first was banned; the ruin of the second forced him to flee from the creditors abroad, where he was to stay for three years. Dostoevsky suffered from epilepsy and had been addicted to gambling for several years . While his contemporaries Lev Tolstoy , Ivan Turgenev and Ivan Goncharov were able to write under conditions of material carelessness, the external circumstances of Dostoyevsky's writing were marked by financial hardship for almost his entire life. For the last ten years of his life, he was financially sound and recognized throughout the country.

life and work

Childhood and youth

The aristocratic name Dostoevsky refers to the now Belarusian village of Dostoevsky near Pinsk , with which one of Dostoevsky's ancestors was enfeoffed. Dostoyevsky's father, Michail Andrejewitsch Dostojewski, was a doctor at Moscow's Mariinsky Clinic for the poor and the son and grandson of Eastern Catholic priests who recognized the authority of the Pope but at the same time followed the Orthodox rite . The ancestors had belonged to a Lithuanian noble branch of the Szlachta . The mother, Marija Fjodorovna, b. Nechayeva, came from a wealthy Moscow merchant family. The couple had eight children, seven of whom reached adulthood. After Mikhail (1820–1864), Fyodor was born on November 11, 1821 (in the Julian calendar : October 30, 1821), the second child. This was followed by Varwara (1822-1892), Andrei (1825-1897), Wera (1829-1896), Nikolai (1831-1883) and Alexandra (1835-1889). After promotion and ennoblement Mikhail Dostoevsky was able to purchase the 1831 Situated outside Moscow Good Darowoje on which the family for some years spent the summer holidays.

The ambitious father strove for social and financial advancement and was very committed to the education of the children. Dostoyevsky initially received elementary instruction from his mother, who also taught her children French . The Russian Orthodox faith played an important role in the family. The mother had literate the sons with religious children's books, and a deacon came into the house for their further religious education . As a child, Dostoevsky was particularly moved by the book of Job . He was a frequent reader and devoured u. a. Derschawin , Karamsin , Schukowski and Pushkin , but also Walter Scott and popular entertainment literature of the time. He learned French a. a. by reading Voltaire's Henriade . From 1833 on, Dostoyevsky and his brother Michail first attended Monsieur Souchard's French boarding school, but in 1834 they switched to Leonti Ivanovich Tschermak's boarding school, which was considered the best in Moscow.

Studies and service as a military engineer

On February 27, 1837, Dostoyevsky's mother died of tuberculosis at the age of 36 . Shortly thereafter, Dostoyevsky passed the entrance examination for the prestigious Military Engineering University in St. Petersburg and began his studies in January 1838. In addition to technical subjects, he also studied Russian and French literature , including Gogol , Hugo and Balzac . George Sand suggested the idea of Christian socialism through her writings . Reading Schiller left a formative impression on him .

On June 6, 1839, Dostoyevsky's father also died on his country estate after a stroke . A neighbor, Pavel Chotjainzew, accused the deceased's serfs of killing him; Dostoyevsky's brother Andrei therefore later believed that his father had been slain. After analyzing Dostoyevsky's life story and the parricide in The Brothers Karamazov in the essay Dostoyevsky and the killing of the father (1928), Sigmund Freud suspected that Dostoyevsky felt guilty for the death of his allegedly murdered father and therefore suffered a first epileptic attack. The Dostoevsky research has not yet confirmed this. Alexander Kumanin (brother-in-law of his mother) and Pyotr Karpenin (husband of his sister Varvara) were appointed as guardians for Dostoyevsky, who was still a minor at the age of 17 . In August 1841 he was promoted to ensign . As an external person, he was able to rent an apartment privately, which he initially shared with Adolph Totleben, whose older brother Eduard Iwanowitsch Totleben later stood up for him both when he returned from Siberia and when he was given permission to move back to St. Petersburg . After class he read and wrote there. He was promoted to lieutenant twelve months later, and graduated a year later. On August 6, 1843, Dostoevsky began his service as a military engineer. In order to be able to stay in St. Petersburg and to have time to write, he accepted an insignificant post as a military draftsman. When he finally threatened to be transferred to a remote military base, he decided to end his career as a military engineer. His resignation was accepted on October 19, 1844. Since the small inheritance was not enough to ensure his livelihood, he now had to earn money by writing.

Writing beginnings

Dostoevsky had been translating French prose as early as 1844; his translation of Balzac's Eugénie Grandet appeared in the summer magazine Repertuar i Panteon . It is known from letters that he also made his own attempts at writing, but these have been lost. Dostoyevsky's first surviving work is the epistolary novel, poor people, written between April 1844 and March 1845 . Dmitri Grigorowitsch , with whom he had been friends since his student days and also shared the apartment since 1844, passed the manuscript on to his friend Nikolai Nekrasov , through whom it came to the influential critic Vissarion Belinsky . Nekrasov and Grigorowitsch introduced Dostoyevsky to Avdotja and Ivan Panayev , in whose salon he read from his work to a specialist audience for the first time. Nekrasov published the novel on January 15, 1846 in his Peterburger Anthologie magazine . Poor people became a huge success. It was the first work in Russian literature to portray people in poverty and misery with all the delicacy and complexity of their emotions and suffering. The Russian intelligentsia greeted it enthusiastically.

Dostoyevski's patron Belinski was a representative of atheistic socialism and successfully promoted his 24-year-old protégé to read Cabet , Leroux , Proudhon and Feuerbach . In early February 1846, he also published Dostoyevsky's novella The Double in the magazine Vaterländische Annalen . The enthusiasm that Belinski and his friends had shown for the debut novel was already gone; they took the second work much cooler. Dostoyevsky soon felt openly rejected in the Belinsky circle. He found refuge in the circle of Nikolai Beketow, who was close to Charles Fourier and utopian socialism . With the Betekow brothers he met the brothers Maikow and Alexei Nikolajewitsch Pleschtschejew , whose poems Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky later set to music. With them, Dostoevsky attended meetings of Mikhail Petraschewski's circle from the winter of 1846/47 .

From autumn 1846 to spring 1849 he published a number of smaller prose works: Herr Prochartschin , A Novelle in Nine Letters , The Landlady , The Strange Woman and the Man Under the Bed , The Weak Heart , Polsunkow , The Honest Thief , Christmas Tree and Wedding and White nights . Most of these stories appeared in the Patriotic Annals . In the spring of 1849 the first parts of Dostoyevsky's novel Njetotschka Neswanowa came out there.

Arrest and trial

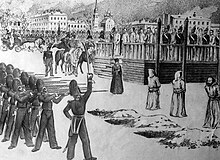

The work remained unfinished. Dostoevsky was arrested in the early hours of April 23, 1849. The Interior Ministry had the Petraschewzen scouted out by an agent provocateur , Pyotr Antonelli. The group's crackdown was a reaction to the European Revolutions of 1848/1849 ; the authority wanted to prevent the surveys from extending to Russia. With Dostoyevsky, 14 other Petraschewzen were imprisoned for state criminals in the Peter and Paul Fortress . In prison, Dostoevsky wrote the short story A Little Hero , which was not published until 1857. Before the military tribunal , Dostoyevsky was charged with attending meetings of the Petrashevzen and reading aloud Belinski's infamous letter to Gogol , in which autocracy , serfdom and religion were severely attacked. All of the accused were sentenced to death . Dostoevsky was 28 years old.

The execution on December 22, 1849 on the parade ground of the Semyonovsky guards turned out to be a mock execution . The condemned were dressed in white corpses and caps; when the first three (Petraschewski, Speschnjeff, Mombelli) were already tied to the pegs, a decree was read out that the auditor general had already presented to the Tsar on November 19. It recommended that Dostoyevsky "... deny all property rights and send him to forced labor in prison for eight years ." Tsar Nikolaus noted under the draft judgment: "For four years. After that, common soldier. ”The Austrian writer Stefan Zweig describes Dostoyevsky's feelings during this event in a chapter of his book Great Hours of Humanity in lyrical form.

Penal camp and military service

Katorga

Dostoevsky began the 3000 km journey to Siberia on December 24, 1849. He arrived at his destination, the Omsk Katorga , on January 23, 1850. The political prisoners were housed with common criminals. The conditions in which the men were housed and kept were very poor. Dostoevsky was kept in chains throughout his detention. He was not allowed to write, but spent some time in the infirmary, where he could secretly keep a notebook.

Dostoevsky completely renounced the idea of revolution and his earlier political convictions during his imprisonment and subsequent military service. All his life, however, he stuck to the ideal of Christian socialism; H. the idea that humanity can create a paradise on earth through its spiritual power.

military service

On February 15, 1854, he was released from Katorga. For health reasons he stayed in Omsk until mid-March and then traveled to Semipalatinsk in western Siberia (today Semei in Kazakhstan), where he had to join the 7th Siberian Line Battalion. Because friends stood up for him, he didn't have to live in the barracks . From the spring of 1855 on, he shared a dacha with Alexander Wrangel , an influential new friend who introduced Dostoyevsky to the local better society; thanks to Wrangel's help, Dostoevsky was also promoted to officer in November 1855. In the spring of 1856 Wrangel even managed to get Dostoevsky allowed to publish literary works again.

Dostoyevsky had already met the Issayev family in 1854. After Alexander Issajew died in 1855, Dostoyevsky courted Marija Issajewa's hand. She finally consented, and on February 6, 1857, the couple were married in Kuznetsk , where Maria was living at the time. Marija brought her 9-year-old son Pavel with her into the marriage. On the journey home to Semipalatinsk, where the couple then settled, Dostoyevsky suffered his first severe epileptic attack and was diagnosed with epilepsy for the first time . He had already suffered from conspicuous symptoms such as loss of consciousness in St. Petersburg and in May 1846 consulted a doctor, Stepan Janowski , about this.

On April 18, 1857, Dostoevsky regained his civil rights. He also began to write again. In 1858 he wrote the novellas Onkelchens Traum and Das Gut Stepantschikowo and its inhabitants . He then wrote the prose work Notes from the House of the Dead and the novel Humiliated and Offended . His health deteriorated so much that he was discharged from military service on March 18, 1859. He was allowed to return to the European part of Russia; however, he was forbidden to settle in St. Petersburg or Moscow. He was placed under police supervision. In July he moved to Tver .

St. Petersburg

After he and friends had written petitions to the new tsar , Dostoyevsky was finally allowed to return from Tver to St. Petersburg in mid-December 1859. After the death of Nicholas I, the political climate had changed significantly: the press could work more freely; In 1861 serfdom was abolished. The works that Dostoyevsky had written in exile were printed, first Uncle's Dream in the magazine Russki Mir (March 1859). Dostoevsky had difficulty in placing the Stepanchikovo estate and its inhabitants in the Patriotic Annals (end of 1859). From September 1860 to the beginning of 1861 the magazine Russki Mir published the introduction and the first four chapters of the notes from a house of the dead ; however, the publication of the following chapters failed due to censorship . Dostoevsky had feared that the censors would offend his exposure of the cruelty of the camp reality. However, that was not the case. On the contrary, one of the censors criticized the fact that Dostoyevsky's description did not deter potential criminals sufficiently. The "Notes" was the first work in Russian literary history that dealt with the life of prisoners and their struggle for elementary dignity in a brutal, inhumane environment in the Siberian penal colonies.

Magazines: Wremja and Epocha

Dostoevsky's brother Mikhail had used the upheaval at the end of the 1950s to obtain the license for a new magazine. He asked Dostoevsky for a contribution to the new magazine, which Dostoevsky promised him from his exile. At the beginning of 1861 the monthly Vremja appeared in which his novel Humiliated and Offended was published from January to July . From the autumn of 1861 to the end of 1862 he gradually published the entire text of the notes from a house of the dead and also in 1862 the short story A Stupid Story .

In 1862 Dostoevsky was doing so well financially that he could afford his first trip abroad. It began on June 7, 1862 and took him via Germany and Belgium to Paris , where he stayed for two weeks and also used the opportunity to consult good doctors. In July he was in London, where he met Alexander Herzen and Mikhail Alexandrowitsch Bakunin and visited the newly constructed and expanded building of the first world exhibition - the Crystal Palace . He then traveled to Switzerland and Northern Italy together with Nikolai Strachow . On this trip he got to know the game of roulette , which, like all games of chance, was strictly forbidden in Russia .

On September 14, 1862, Dostoyevsky returned to Saint Petersburg and - inspired by his travel experience - wrote an essay Winter Notes on Summer Impressions , which appeared in Vremja the following February . In it he also described the disgust he had felt for the materialism of European cities - especially in London. After Strachow had written an article for Wremja about the Russian-Polish relationship, which the censors perceived as critical of the government, the magazine was banned on May 24, 1863.

Dostoevsky had probably already started a love affair with the young Polina Suslowa in winter . From August to October 1863 he undertook his second trip abroad, which again led to Paris, where he met Suslowa this time. She accompanied him to Baden-Baden , where he visited the casino . In November 1863, Dostoevsky moved to Moscow with his wife, who was suffering from tuberculosis , to receive medical treatment there.

In January 1864, together with his brother Michail, he founded the monthly newspaper Epocha , which was to succeed the banned Wremja . Dostoevsky started the magazine on March 21st with the first episode of his prose work, Notes from the Cellar Hole . In it he reduced Chernyshevsky's idea of a “reasonable egoism” to absurdity. Walter Kaufmann later called the book "the best overture on existentialism that has ever been written" . Orhan Pamuk literarily points out the importance of the novel for the following works. On April 15, his wife died and, surprisingly, on July 22, 43-year-old Mikhail also died; Dostoevsky agreed to feed his widow and children. Epocha had never matched the commercial success of Wremja and was heavily in debt. In June 1865 Dostoyevsky had to stop operations; the satirical story The Crocodile , which he began to publish in February, remained unfinished. Then Dostoyevsky traveled a third time to the West, where he, again in the company of Polina Suslowa, gambled away 3,000 rubles in Wiesbaden at the end of July.

Six great novels

Crime and Punishment

Dostoevsky had been busy with his next work, Crime and Atonement , as early as 1864 . The novel appeared from January to December 1866 in the monthly Russki Westnik and in 1867 in book form; it was just as successful with the public as it was with criticism. Guilt and Atonement tells the story of the student Rodion Raskolnikow, who out of arrogance and constant lack of money becomes the murderer of a lender, but finds a new ethical attitude in the prison camp and through the love of a woman. It was the first of the great novels of ideas that are at the center of Dostoyevsky's oeuvre. All deal with the effect of reality on the next generation; their concern was a diagnosis of the present, i. H. the years 1865–1875, which were marked by a fundamental intellectual upheaval in Russia.

The player

In 1866, Dostoevsky began working on “Guilt and Atonement”, the much shorter novel The Gambler . Dostoevsky found himself in a financially hopeless situation in June 1865 after the collapse of the magazine "Epocha". In order to raise another 3,000 rubles , he signed a contract with the publisher Stellowski, which he u. a. obliged to deliver a novel with a volume of at least ten printing sheets by October 31, 1866. After he hadn't written a line for this novel for a year, he hired a stenographer , 20-year-old Anna Snitkina , at the last minute on October 4th , with whose help he delivered the novel on time. The Gambler was Dostoyevsky's only novel that did not appear as a feature novel. Stellowski was a bookseller and prepared the first complete edition of Dostoyevsky's work, which was to contain the short novel as a bonus text. Dostoevsky and Snitkina got close through work. On November 8th, he proposed marriage to her. The wedding took place on February 15, 1867 in the Trinity Cathedral .

The idiot

Dostoevsky could not handle money, had debts and a number of relatives who wanted to be looked after. Anna wanted to take control of the money into her own hands and was convinced that this would be easier if they went abroad for a while; initially three months were planned. She mortgaged her dowry to finance the trip . Shortly before leaving, two of the creditors made demands. The couple decided to stay abroad until Dostoevsky was better off financially thanks to new jobs. The journey began on April 14, 1867 and initially led to Dresden . Again, however, Dostoevsky was drawn to roulette in Homburg and Baden-Baden, where he again lost money. In Baden-Baden he fell out with Turgenew, who had supported him occasionally until then. The couple traveled via Basel to Geneva in mid-August , where Anna gave birth to Sonja on March 5, 1868, who died after just three months.

As early as the summer of 1867 Dostoevsky had the plan for a new novel, The Idiot . He began writing in Geneva, but most of it originated in Vevey , where the couple settled in May 1868. From January 1868 on, the novel appeared in sequels in Russki Westnik . Later parts were made in Milan and Florence , where Dostoevsky completed the work in January 1869. The intellectual experiment he carried out in The Idiot consisted in placing a “perfectly good and beautiful person” - the young Prince Myshkin - after a long stay abroad in the contemporary Russian environment, which of course ends in the greatest possible debacle after a complicated plot . As with all his works, this novel was also characterized by a high degree of intertextuality : with his portrait of a “good person” Dostoevsky made extensive reference not only to the New Testament and the interpretations of Christ by Ernest Renan and David Friedrich Strauss but also to the heroes of Miguel de Cervantes , Charles Dickens and Victor Hugo .

The demons

Anna and Fyodor Dostojewski lived in Dresden from mid-August 1869 to the end of 1870 . On September 26, 1869, their daughter Lyubov Fyodorovna was born, who later became her father's writer and biographer. Shortly before, he had begun writing the novel The Eternal Husband , which he completed in December and published in Strachow's magazine Saria in early 1870 .

On November 21, 1869, the murder of Ivan Ivanov, a student belonging to Narodnaya Rasprawa , an underground revolutionary organization founded by Sergei Nechayev , occurred in Moscow . After a difference of opinion, he was killed by his own comrades in arms. The incident, which was also heard in Dresden, stimulated Dostoyevsky's imagination enormously; he saw the nihilist Nechayev as the ideological descendant of the liberal thinker he himself had been in the 1840s. Nechayev, who was apparently ready to commit the most hideous crimes for the revolution, confirmed Dostoyevsky's worst expectations in this regard, which is what Chernyshevsky's materialist and atheist position - consistently thought through to the end - amounted to. The next great novel, The Demons , which Dostoevsky worked on from December 1869 to November 1872, emerged from these considerations . It appeared in sequels in Russki Westnik from January 1871 to December 1872.

After Notes from the Basement Hole and Guilt and Atonement , The Demons were Dostoyevsky's third and final anti-nihilistic work. His diagnosis of the spiritual situation of the time reached its lowest point of hopelessness. From the murder, Dostoevsky developed the tricky and surrealistic scenario of a world out of joint, in which almost everyone involved sooner or later despair. With the complex main character Stavrogin, an amoral superman acting beyond good and evil , Dostoevsky has created a dark counterpart to the Christ- like Prince Myshkin. The genealogy of ideas from the history of ideas is clearly worked out, naming the enlightened generation of the 1840s as the fathers of the nihilists of the 1860s. On the other hand, Stepan Verkhovyensky - the most important representative of the 1840s in the novel - comes very close to Dostoevsky's ideal of Christian socialism.

In April 1871 Dostoevsky went to Wiesbaden for the last time to gamble. In July he received an advance of 1,000 rubles for The Demons , which enabled him to return to Saint Petersburg with his family. A few days after their arrival, on July 16, 1871, their son Fyodor was born. Dostoyevsky completed the manuscript for the novel The Demons in November 1872. It appeared in sequels in Russki Westnik from January 1871 to December 1872.

The youth

Since he lived in Saint Petersburg again, Dostoyevsky had become friends with a number of influential people, including that of Konstantin Pobedonoszew , who later became the " gray eminence " of Alexander III. has been. In March 1878, Pobedonoszew helped Dostoevsky to be invited to the tsar's residence , where he was allowed to hold several doctrinal conversations with his sons Sergei and Pawel . Dostoevsky also made friends with the young philosopher Vladimir Solovyov and with Sofja Andreevna Tolstaya, the widow of the poet Alexei Konstantinovich Tolstoy .

In early 1873, Prince Vladimir Meshchersky entrusted Dostoyevsky with the editing of his conservative weekly Graschdanin . At irregular intervals Dostoyevsky published the column Diary of a Writer in it , which dealt with a wide range of political, religious and philosophical topics and which was extremely popular in its time, but was also criticized in the 20th century for Dostoevsky's anti-Semitic position. In the sixth edition of 1873, his short story Bobok also appeared here .

After Dostoyevsky had spent two days in prison for violating censorship regulations, he left the Graschdanin in April 1874 . He had been preparing a new great novel, Der Jüngling , since February and began writing it in early November. He developed his analysis of Russian reality on an ego-centered young man, Arkadij Dolgorukij, who does everything in his power to achieve money, social power and, above all, unlimited personal autonomy . The Petersburg world of citizens and nobles, in which Arkadij moves, turns out to be out of order and morally decrepit. The central element of the novel is the gradually developing relationship between Arkady and his birth father, around whom his thoughts and longings revolve. The novel appeared in January 1875 in the Fatherland Annals .

The Dostoevskis have been spending every summer in the spa town of Staraya Russa since 1872 . On August 10, 1875 the son Alexei ("Aljoscha") was born there. In 1876 Dostoevsky also bought a small house in Staraya Russa. Since he suffered from emphysema , he had visited Bad Ems several times for therapy purposes since 1874 .

The Karamazov brothers

In January 1876, Dostoevsky began to publish the diary of a writer , which had not appeared after his departure from Grahdanin , on his own account. In November 1876 he published his novella Die Gentle in the diary and in April 1877 in Graschdanin the story The dream of a ridiculous man .

The family spent the summer of 1877 in Maly Prikol near Kursk , where Anna's brother Ivan owned a country estate. On May 16, 1878, the youngest child, Aljoscha, almost three years old, died unexpectedly. In June, beside himself with pain, Dostoevsky made a pilgrimage to the Optina monastery near Koselsk , where he sought consolation from Starez Amvrossi ; Dostoyevsky later used his impressions of this man in his novel The Brothers Karamazov for the character of Starez Sosima. He had started taking notes for this novel in April; At the beginning of November 1880 he graduated. The novel The Brothers Karamazov , the most extensive of Dostoevsky's novels, is highly complex due to the immense number of characters and the many storylines in which Dostoevsky revisited all the ideas and human designs that had moved him up to that point. The central questions that the protagonists answer in their own way are those about the existence of God and the meaning of life. The subject is criminalistic: Fyodor Karamazov, a dissolute old man, is hated by his four very different sons and killed in his mind. After his murder, two of them are suspected, but the other two feel morally responsible. Dostoyevsky's artistic anthropology reaches its climax here, which led Sigmund Freud to judge that this was "the greatest novel that has ever been written". The novel was published in many episodes from January 1879 to November 1880 in Russki Westnik .

The last years of life

In the last years of his life, during which he was increasingly ill, Dostoevsky received many honors. When Nikolai Nekrasov died in November 1877 , Dostoyevsky gave the funeral speech . On December 2, 1878 he was elected Correspondence Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences . On February 3, 1880, the Slavic Charity Society in Saint Petersburg elected him its vice-president. On the occasion of the inauguration of a Pushkin monument, Dostoyevsky gave a speech about the poet on June 8, 1880 , in which he celebrated Pushkin as the prophet of Russia.

Dostoyevsky's health deteriorated rapidly. From February 7, 1881, he suffered from pulmonary bleeding, which led to his death on the evening of February 9 ( January 28 according to the Julian calendar ).

Tens of thousands of people took part in the funeral procession that led from Dostoyevsky's apartment across Nevsky Prospect to the church of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery on February 12 . The funeral at which Solovyov gave the speech took place one day later in the Tikhvin cemetery belonging to the monastery . His gravestone bears the word of Christ as an inscription:

“Verily, verily, I say to you: If the grain of wheat does not fall into the earth and die, it remains alone; but when it dies, it bears a lot of fruit. "

Literary style

Dostoyevsky's writing is characterized by a great synthesis of artistic styles and forms of expression. He has taken influences from the Enlightenment (Voltaire), sentimentalism (Rousseau), Schiller, ETA Hoffmann , Pushkins, Gogols, Lermontows , Balzacs, George Sands and Charles Dickens' and placed them in new contexts. The same applies to the urban poverty-stricken environment discovered by the naturalists and to the criminalistic subjects - otherwise found in sensational novels. Mikhail Bakhtin has compared Dostoevsky's writing with Menippeian satire , a “carnivalised” literature that mixes the serious with the ridiculous and in this way concisely expresses the eccentric, extreme and ambivalent that interested Dostoevsky so much, with the limits of realism are exceeded again and again. The tendency towards the comic can also be found in his little-known poems, some of which he has interspersed in his novels. Felix Philipp Ingold describes it as "nonsense poetry" and finds in it "the meticulous combination of strict form and comedy".

Dostoevsky always went beyond the framework of the literary schools from which he learned. This already applies to the first work, poor people , whose meticulous description of the milieu was strongly influenced by naturalism; the meticulousness with which Dostoevsky portrayed this milieu not only from the outside, but also in the finest thoughts and emotions of the two protagonists, was his personal ingredient, which he skillfully balanced with the naturalistic portrayal of the exterior.

As Wolf Schmid has shown, the narrative methods of modern prose first came to full fruition in Dostoyevsky's second novel, The Double . The narrative process and the plot are here in a complex mutual dependency, and with calculated indeterminacy the reader is kept in the dark until the end whether he is dealing with a story of paranoia or a purely fantastic event. The intricately intertwined structure makes it possible to interpret the doppelganger on very different levels , for example as a psychological, analytical, socially critical or philosophical novel.

Dostoyevsky's novel composition in Schuld und atonement reached the next high point , in which the technique of the experienced speech , the scenic performance, the "carnivalization" and the drawing of unconscious processes were fully mastered. In The Idiot , it was the characters' speaking behavior and dialogue that Dostoevsky paid particular attention to. In the following two works, The Demons and The Young Man , he used first-person narrators . Their perception was subjectively distorted in each case - in the demons by the honest mentality of the narrator, in the young man by his age-appropriate excessive demands - which means that the stories remain puzzled almost to the end and the confusion of the characters, who move in completely out of joint worlds , with the narrative situation is complexly fed back. The diagnosis of the social condition as chaos became the structural principle of these two novels, especially in the little-read youth . Finally, the novel The Brothers Karamazov , with its many characters, episodes and lines of development, is Dostoevsky's most complex work and the one in which the “polyphonic” structure described by Bakhtin is most clearly visible. Each of the brothers is assigned an independent key text, the most famous of which is the legend of the Grand Inquisitor (= Ivan's self-portrayal). Because of its well-calculated complexity, the novel can be read and interpreted as an allegory , as a theodicy , as a family drama, as a social novel, as a philosophical, as a psychological novel, and even as a detective novel.

Rosa Luxemburg pointed out the dramatic elements of Dostoyevsky's novels: they were so bursting with plot, experience and tension that their overwhelming, confusing abundance threatened to crush the epic element of the novel, threaten to break its barriers at any moment. Horst-Jürgen Gerigk examined this mode of action and described it as Machiavellian. Crime, disease, sexuality, religion and politics would be used purposefully to captivate the reader. Dostoevsky achieved the tension through polarization (poor / rich; old man / young woman; villain / good person). Things and characters are not fully told. The reader has to construct something through a series of moves, hints and conversations, but this is never enough to create a perfectly logical expectation. Often a narrator appears who does not understand the whole thing, does not notice a lot and reports of rumors. The silence or the vague suggestion of motifs are further elements of the deliberately built tension. Often money gives events a completely unexpected direction. Many of the people have a stab of crazy or strange airs. The incomprehensible is exaggerated.

Estate and reception

Reception in Russia and the USSR

The first complete edition of Dostoyevsky's work appeared in 1881. Orest Miller and Nikolai Strachow published the first biography of the writer in 1883 . Four of the great novels were filmed in 1915.

After the October Revolution

The reception of Dostoevsky had already been ambivalent in the 19th century. When Nikolai Michailowski published the novel Der Jüngling in his left sheet Otetschestvennye Sapiski in 1875 , he had to explain to his subscribers why he wanted to give space to the author of the anti-socialist novel The Demons . The ambivalence only increased during the Soviet Union . Because their artistic value was beyond question, Dostoyevsky's works were printed in higher editions than ever before. 1926–1930 the Soviet state publisher published a thirteen-volume complete edition edited by Boris Tomaschewski and Konstantin Schalabajew. In 1918, a Dostoyevsky monument was unveiled in Moscow, with speakers praising the writer as a “prophet of the revolution”, a position also held by many moderate Marxists, including the influential critic Valerian Perewerzew . However , it has also been bitterly criticized because of the philosophical, ideological, and religious beliefs that were expressed in Dostoevsky's work, which diametrically opposed Marxism . One of the sharpest opponents was Maxim Gorky , who ruled in 1913 that Dostoyevsky's “reactionary” positions could not be excused by his artistic genius, and Lenin agreed with this. The latter rejected Dostoyevsky not only because of the novel The Demons , but also because of the notes from the basement hole , which were directed against Chernyshevsky's philosophy . Not only the content of Dostoyevsky's work was received controversially. A debate about the form of his writing in the 1920s gave rise to one of the most important works that the Russian-speaking world has produced on this subject: Mikhail Bakhtin's Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics (1929). Bakhtin named polyphony as the fundamental structural principle of Dostoyevsky's novels : Dostoyevsky's fictional characters are not representations of the author's voice distributed over different roles, but rather autonomous carriers of consciousness and world views that contest a polyphonic dialogue with one another. Dostoyevsky's personal standpoints hardly came to the fore in his novels. Many Marxists rejected Bakhtin's theses, and in the year of publication he was sent into exile in Kazakhstan .

Stalin Era and Socialist Realism

The conditions for a free discussion of Dostoyevsky's work reached their low point during the period of Socialist Realism . Even Viktor Schklowskis 1931/32, undertaken attempt motifs from the records of House of the Dead for an experimental film to use, had ended as a socialist propaganda film. As chairman of the Soviet Writers' Union in 1934, Gorky set the official party line that would apply to the treatment of Dostoyevsky until the end of the Stalin era . Scientific publications from then on concentrated on ideological issues. Already announced publications of letters and a single edition of the novel The Demons did not materialize, and with the exception of Grigori Roschal's Peterburgskaya (1934) no further film adaptations were made until 1958.

With his poetic attempts Dostoyevsky became a forerunner of the absurd poetry of Russian modernism. Nikolaj Oleijnikov, who was executed in the course of the Stalinist purges of 1937, referred to Dostoevsky quite explicitly in his poem "The Cockroach".

When during the Second World War there was a need for national identification figures who were supposed to fuel patriotism, Dostoyevsky was temporarily rehabilitated, for example by Vladimir Ermilov, who now interpreted The Demons as a brilliant prophetic portrait of modern fascism . Jemeljan Jaroslawski even celebrated Dostoyevsky because of his indignation against the Germans. Arkadij Dolinin and Valery Kirpotin published books about him that deviated from the ideological mainstream. Dolinin defended Dostoevsky as a visionary of a human future that would ultimately get by without the concept of God. When the Zhdanov theory prevailed in the late 1940s , Dostoyevsky, like many other Russian authors, came under renewed criticism. The Ministry of Culture instructed the universities to convey to their students that Dostoyevsky's works were “an expression of the reactionary bourgeois individualistic ideology” . The important biography of Dostoyevsky by Konstantin Motschulski was not published in the USSR in 1947, but by a Paris publishing house.

From 1955 to the present

Permanent liberalization only came about with the rise of Khrushchev . In 1955 the guidelines for the Dostoevsky studies were relaxed somewhat. In 1956 a stamp with Dostoyevsky's portrait appeared for the first time ; another followed in 1971. The writer Vladimir Bontsch-Brujewitsch stated in an article that Lenin held Dostoevsky in great esteem. From 1956 to 1958 a new ten-volume complete edition was published, supervised by Leonid Grossman. New literary studies emerged, and for the first time since the October Revolution , a significant number of film adaptations of Dostoyevsky's novels were released, including Ivan Alexandrovich Pyrev's The Idiot (1958) and Pyrev and Kirill Lavrov's version of the Karamazov brothers (1968).

From 1972 to 1990 a thirty-volume critical academy edition was published, supervised by Georgi Fridlender , which is considered an editorial highlight and which has stimulated a wealth of new secondary literature and new translations.

In 1981, Alexander Sarchi's feature film, 26 Days from the Life of Dostoevsky, was released in cinemas and also attracted international attention when the leading actor, Anatoly Solonitsyn , received the Silver Bear for best actor at the Berlinale . Leonid Zypkin's novel A Summer in Baden-Baden (1982), on the other hand, could initially only be published in the USA; only in 1999 did he appear in Russia. In 2011, the mini-series Dostoyevsky was shown on Russian television , directed by Vladimir Chotinenko and Yevgeny Mironov in the title role. Dostoyevsky's person and work are considered to be trend-setting by the Russian New Right . The painter Ilja Glasunow , himself a supporter of the pre-revolutionary monarchist order, addressed the overriding importance of the writer for Great Russian historical thinking in the 1990s in the monumental painting Eternal Russia , in which he gave Dostoyevsky the central place in the pantheon of Russian national saints and historical actors.

Translations into German and other languages

The earliest German translation is an excerpt from poor people , which Wilhelm Wolfsohn published only a few months after the appearance of the Russian original in his magazine Russische Revue . Extensive translations of Dostoyevsky's work into German began only after the author's death. The first was William Henckel with Raskolnikov (1882); there followed translations and a. the novels The Brothers Karamazov (1884, unnamed translator), Humiliated and Offended (1885, Constantin Jürgens), Young Offspring ( Der Jüngling ; 1886, W. Stein), The possessed (Herbert Putze, 1888), The Idiot ( August Scholz 1889 ) and finally, in 1890, Hans Moser's version of Guilt and Atonement , which for a long time gave this novel an unhappily translated title. Just eight years after Dostoyevsky's death, all five great novels and many of his smaller works were available in German. Other early German translators were LA Hauff and Paul Styczynski. The first German biography of Dostoevsky was published in 1899.

In the early 20th century, Elisabeth Kaerrick translated Dostoyevsky's complete works under the pseudonym E. K. Rahsin , with the help of her sister Lucy Moeller and Arthur Moeller van den Bruck . The series comprises 22 volumes and seven additional volumes and was published between 1906 and 1922. It helped the young Reinhard Piper achieve a brilliant rise in his Piper Verlag, founded in 1904 . Less well known are the translations by Werner Bergengruen , Alexander Eliasberg , H. v. Hoerschelmann, Gregor Jarcho, Valeria Lesowsky, Arthur Luther , Hermann Röhl and Arnold Wasserbauer.

In the German Democratic Republic , the Aufbau-Verlag created a thirteen-volume edition that was completed in 1990 and includes the entire fiction work. Margit and Rolf Bräuer , Werner Creutziger, Günter Dalitz, Hartmut Herboth, Wilhelm Plackmeyer, Dieter Pommerenke and Georg Schwarz contributed to the translation . Incidentally, the German-speaking written after World War II u. a. Klara Brauner, Johannes von Guenther , Richard Hoffmann , Marianne Kegel, Hans Ruoff and Ilse Tönnies new German translations. Swetlana Geier , who translated the five great novels from 1988 to 2006, received the most attention . She introduced three of them under a new title: Crime and Punishment ( Guilt and Atonement ; 1994), The Idiot (1996), Evil Spirits ( The Demons ; 1998), The Karamazov Brothers (2003) and A Green Boy ( The Young Man ; 2006). They were first published by Ammann and from 2006 also as Fischer paperbacks. Geier has also re-translated some of Dostoevsky's smaller works.

In other European countries too, translation work did not begin until after Dostoyevsky's death. Similar early as in German-speaking individual works of Dostoyevsky have been translated into Swedish ( Kränkning och Förödmjukelse / Humiliated and Insulted , 1881; Anteckningar från Det Döda Huset / Notes from the House of the Dead , 1883), Czech ( Aninka Nesvanova / Njetotschka Neswanowa , 1882), Danish ( Fattige Folk / Poor People , 1884; Raskolnikov , 1884), Norwegian ( Raskolnikow , 1884) and French ( Humiliés et Offensés / Humiliated and Offended , 1884; Le crime et le châtiment / Guilt and Atonement , 1884). In 1885 the first translations into Dutch ( Schuld en Boete / Schuld und Sühne ) and English ( Crime and Punishment / Schuld und Sühne ) followed.

International reception

Theology, Philosophy, Psychology and Society

The influence that Dostoevsky exercised on the history of Western intellectual and literary history has been immense and has been described in countless scientific publications. Friedrich Nietzsche is likely to have read - in French translations - the humiliated and insulted , notes from a house of the dead , The Idiot and The Demons . He admired Dostoyevsky's psychological insight and felt that he was a "worthy opponent". In dealing with Dostoyevsky's novels, he had the opportunity to work through his own highly ambivalent relationship to Christianity. Many of Nietzsche's writings, including Der Antichrist (1894), are immediate fruits of this reception. The theorists of Russian symbolism , such as Dmitri Mereschkowski , also advocated a philosophy of religion based on Dostoyevsky. In the German-speaking world, Dostoyevsky's understanding of God through Eduard Thurneysen's and Karl Barth's dialectical theology had a great influence on Protestant thought .

Hermann Hesse understood the Karamazov brothers as a prophecy of the downfall of the European spirit. Dostoyevsky's ambiguous sentence "We are revolutionaries (...) from conservatism" was taken up by Thomas Mann in 1921 and converted into the catchphrase of a " conservative revolution "; Arthur Moeller van den Bruck then popularized this catchphrase.

Decades before the establishment of psychoanalysis , Dostoevsky meticulously sounded out the human soul, showed its internal contradictions and the power of the unconscious , and tried to rehabilitate the irrational . Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler studied his work and were able to draw their lessons from discoveries that Dostoevsky had already presented in detail. The Danish Slavist Adolf Stender-Petersen characterized Dostoyevsky's writing as "psychological realism". In the 1920s, Dostoyevsky's preoccupation with the irrational also caught the attention of the Surrealists , especially André Breton .

The existentialists felt addressed by Dostoyevsky because he had repeatedly described man as someone who was completely abandoned in God forsaken. For Jean-Paul Sartre, Dostoyevsky's thesis “If God is dead, then everything is allowed” was the starting point of existentialism. For Albert Camus , too , the struggle with the nihilism that Dostoyevsky had exemplified was the program.

In the 1980s, contributions a. a. by David I. Goldstein and Felix Philipp Ingold a debate on Dostoyevsky's anti-Semitism , which was mainly shown in the diary , as stereotypical, contemptuous and ridiculous drawing of Jewish figures, which is also in the notes from a house of the dead , in guilt and atonement and in Die Demons has become visible.

Dostoyevsky's reflections on Russian identity under the onslaught of Western values have recently stimulated Orhan Pamuk to re-understand Turkish identity.

literature

Dostoevsky is considered to be the new founder of European fiction, a position that - depending on the author - is also awarded to Diderot ( Rameau's nephew , 1805) and Flaubert ( Madame Bovary , 1858). Characteristics of the modern novel are the replacement of the hero by the average person, the abolition of the omniscient, Olympic narrator and the abandonment of the chronological and causal structure of action in favor of an event that is reflected in the consciousness of the characters. The genealogical series, with which this development is often symbolized, leads from Dostoevsky to Marcel Proust , Franz Kafka , James Joyce , André Gide and William Faulkner to the Nouveau roman . With the exception of Faulkner, in whose work there is no evidence that he actually read Dostoevsky, all of these authors were familiar with the works of Dostoevsky and valued him very much.

Like Henry James , Joseph Conrad , Marcel Proust, Virginia Woolf , James Joyce and Franz Kafka after him , Dostoevsky no longer described reality , but introduced doubt and ambiguity into the world of the novel . In place of an orderly, almost scientific architecture with strict causality of the motifs and acts, Dostoevsky gave an intuitive, irrational view of the world, free association and literary means such as leitmotifs , parallel episodes, contrasting themes and scenes. Authors such as Thomas Mann, Virginia Woolf and Aldous Huxley have adopted and developed his principles of thematic composition. Dostoyevsky's preference for narrative techniques such as the inner monologue and confession also testifies to the primacy of the subjective ; These were adopted by German literary expressionism , especially Paul Kornfeld and Franz Werfel , but also by non-western authors such as B. Dazai Osamu . The visionary fantastic in Dostoevsky and his satire have strongly influenced Gabriel García Márquez , among others . Dostoevsky's penchant for the surreal has inspired popular literature, especially Jim Thompson .

Knut Hamsun ( Hunger , 1890), Italo Svevo ( Zeno's Conscience , 1923) and Yukio Mishima ( The Temple of Dawn , 1956) have orientated themselves to Dostoevsky as anatomists of the extreme complexity of the human soul . His preoccupation with the dark side of souls has a. a. Thomas Mann ( Buddenbrooks , Der Zauberberg , Doktor Faustus ), Robert Walser and Marek Hłasko .

Many later writers - including John Cowper Powys , Jakob Wassermann , Mikha'il Na'ima, Mahmud Taymur, Roberto Arlt , Yahya Hakki , Octavio Paz , Charles Bukowski , Jaan Kross and Orhan Pamuk - saw Dostoyevsky as their literary idol and are thematic to him and followed stylistically. Time and again, readers have become enthusiastic about the emotional intensity ( Nadryw ) that is constantly kept in full swing in Dostoyevsky's novels with topics such as illness, obsession, passion, perversion, crime, suicide , remorse, penance and self-sacrifice; Ernest Hemingway is an example of this , who wrote in the 1920s: “With Dostoevsky there were both believable and unbelievable things, but some of them are so true that reading them makes you a different person; with him one could get to know weakness and madness, wickedness and holiness and the madness of gambling […] ” .

The heated atmosphere of the novels, which is overflowing with religious, psychological, philosophical and often also literary ideas, did not please everyone. For example, the English poet Edmond Gosse wrote in 1926: “I should say to every deserving young writer who speaks to me: 'Read what you like, just don't waste your time reading Dostoevsky. He is the cocaine and morphine of modern literature. ' " Even Milan Kundera has revolted against it, as Dostoevsky feel declare its own sake to a value.

In the United States , the reception of Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé's standard work Le roman russe and the tendentious translations by Constance Garnett Dostoevsky put him in a light in which he appeared as a great outsider of the European literary tradition and could take the rank of a cultural icon. Many authors - especially Henry Miller - adored him enthusiastically, but without following him authoritatively or ideologically. Representatives of the Beat Generation such as Allen Ginsberg , Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs declared themselves to be Dostoevsky's successors without even taking notice of his ideological and religious positions. Other writers, on the other hand, such as Upton Sinclair and Ezra Pound , who had read Dostoyevsky's work more critically, were simply repulsed.

Adaptations

Long before literary and media scholars like Irmela Schneider theoretically outlined the problem of literary adaptation, Dostoyevsky was so clear about some of the central difficulties involved in transforming texts that he not only spoke to Varwara Obolenskaya, who began a dramatization of guilt and atonement in 1871 strategic advice, but also an elementary theory of adaptation. Dostoyevsky's works pose particular difficulties for adaptation, and not just because of their length; neither their polyphonic structure nor their intertextuality can be transferred to other genres or media. Artists around the world have found themselves challenged by these difficulties, and many attempts have been made to translate Dostoevsky's prose into a wide variety of other art forms. Unlike the adaptations of works e.g. Adaptations of Dostoyevsky's prose, for example Pushkins, Gogols, Tolstois or Chekhovs, show a tendency to hardly resemble the source texts. Successful adaptations include: a. Sergei Prokofiev's opera The Gambler (1929), Leoš Janáček's opera From a House of the Dead (1930), Mieczysław Weinberg's opera The Idiot , op.144, (1985), Luchino Visconti's feature film White Nights (1957) and Andrzej Wajda's stage version of The Possessed (1971 ).

- → For adaptations of individual works by Dostoyevsky, see the respective articles.

Research facilities and museum

The world's most important research center on Dostoevsky is the Institute of Russian Literature (IRLI, “ Pushkin House ”) in Saint Petersburg, whose archive also contains many of the author's manuscripts. In the USA there is a research focus at the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Illinois at Urbana / Champaign.

The Petersburg apartment in which Dostoevsky lived from 1878 until his death (Kuznetschny pereulok 5/2) has housed a museum since 1971.

Dostoevsky's works

Novels

- (1846) Poor people (Russian: Бедные люди, scientific transliteration: Bednye ljudi )

- (1849) Njetotschka Neswanowa (Неточка Незванова, Netočka Nezvanova ; fragment)

- (1861) Humiliated and Offended (Униженные и оскорбленные, Unižennye i oskorblënnye )

- (1866) Guilt and Atonement (Преступление и наказание, Prestuplenie i nakazanie )

- (1867) The Gambler (Игрок, Igrok )

- (1869) The Idiot (Идиот, Idiot )

- (1872) The demons (Бесы, Besy )

- (1875) The youth (Подросток, Podrostok )

- (1880) The Karamazov Brothers (Братья Карамазовы, Brat'ja Karamazovy )

Novellas

- (1846) The Doppelganger (Двойник, Dvojnik )

- (1847) A novella in nine letters (Роман в девяти письмах, Roman v devjati pis'mach )

- (1847) The landlady (Хозяйка, Chozjajka )

- (1848) The weak heart (Слабое сердце, Slaboje serdce )

- (1848) Christmas tree and wedding (Ёлка и свадьба, Ëlka i svad'ba )

- (1848) White Nights (Белые ночи, Belye noči )

- (1859) Uncle's Dream (Дядюшкин сон, Djaduškin son )

- (1859) The Stepanchikovo Estate and its inhabitants (Село Степанчиково и его обитатели, Selo Stepančikovo i ego obitateli )

- (1864) Records from the basement hole (Записки из подполья, Zapiski iz podpolʹja )

- (1870) The Eternal Husband (Вечный муж, Večnyj muž )

- (1876) The gentle one (Кроткая, Krotkaja )

stories

- (1846) Mr. Prochartschin (Господин Прохарчин, Gospodin Procharčin )

- (1848) The Strange Woman (Чужая жена, Čužaja žena )

- (1848) The jealous husband (Ревнивый муж, Revnivyi muž )

- (1848) Polsunkow (Ползунков, Polzunkov )

- (1848) The Honest Thief (Честный вор, Čestnyj vor )

- (1849) A Little Hero (Маленький герой, Malen'kij geroj )

- (1860) The strange woman and the man under the bed (Чужая жена и муж под кроватью, Čužaja žena i muž pod krovat'ju )

- (1862) Records from a house of the dead (Записки из Мёртвого дома, Zapiski iz mërtvogo doma )

- (1862) A stupid story (Скверный анекдот, Skvernyj anekdot )

- (1865) The Crocodile - An Unusual Event (Крокодил, crocodile ; fragment)

- (1873) Bobok (Бобок)

- (1876) The boy with the Lord Jesus at Christmas (Мальчик у Христа на ёлке, Mal'čik u Christa na ëlke )

- (1876) The centenarian (Столетняя, Stoletnjaja )

- (1877) The Dream of a Ridiculous Man (Сон смешного человека, Son smešnogo čeloveka )

Essay Collections

- (1863) Winter notes of summer impressions (Зимние заметки о летних впечатлениях, Zimnie zametki o letnich vpečatlenijach )

- (1873–1881) Diary of a writer (Дневник писателя, Dnevnik pisatelja )

Translations

- (1843) Eugénie Grandet ( Honoré de Balzac )

- (1843) La dernière Aldini ( George Sand )

Current total editions

Russian:

- VG Bazanov (ed.): Polnoe sobranie sočinenij. V tridcati tomach ( Полное собрание сочинении в тридцати томах) . Izdat. Nauka, Leningrad, ISBN 5-02-027952-8 (1972–1990, complete works in thirty volumes).

German:

- All novels and stories . 13 volumes. Structure, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-351-02300-6 .

- All works . 10 volumes. Piper, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-492-25265-2 (German by EK Rahsin).

- All works . 37 volumes on a USB stick including diaries. anchor eBooks, 2011, ISBN 978-3-942963-00-8 (digital edition).

Literature on Dostoevsky

reference books

- Richard Chapple: A Dostoevsky Dictionary . Ardis Publishers, Ann Arbor, Michigan 1983, ISBN 0-88233-616-9 (English).

- Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

Trade journals

- Materialy i issledovanija (MiI) . "Official journal" of the Soviet Dostoevsky research. (since 1974).

- The Dostoevsky Journal. An Independent Review . Charles Schlacks, ISSN 1521-1975 ( dostoevskyjournal.com - since 2000).

- International Dostoevsky Society (Ed.): Dostoevsky Studies. Volumes 1–9, University of Toronto, 1980–1988 ( utoronto.ca ( Memento of December 21, 2013 in the Internet Archive )).

- Dostoevsky Studies - The Journal of the International Dostoevsky Society . New Series Band 1 -16. Attempto, ISSN 1013-2309 (since 1998).

- Yearbook of the German Dostoyevsky Society . Otto Sagner, ISSN 1437-5265 (since 1993).

Biographies

To get started

- Lotte Bormuth : Poet, thinker, Christian: The life of Fjodor Dostojewski , Francke Verlag, Marburg 2000, ISBN 978-3-86122-455-6 , edition 2003, ISBN 978-3-86122-645-1 .

- Vitali Konstantinov : FMD: Life and Work of Dostoyevsky . Knesebeck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-86873-850-6 .

- Ulrike Elsässer-Feist: Fyodor M. Dostojewski . Brockhaus, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-417-21110-7 .

- Janko Lavrin: Dostojewski (= Rowohlt's monographs . No. 50088 ). 29th edition. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-499-50088-6 .

- Zenta Maurina : Dostoyevsky. Shaper and seeker of God . Maximilian Dietrich, 1997, ISBN 978-3-87164-100-8 (Latvian: Dostojevskis . 1931.).

For exact study

- Nina Hoffmann: Th. M. Dostojewsky . Ernst Hofmann & Co., Berlin 1899.

- Julius Meier-Graefe : Dostojewski the poet . Ernst Rowohlt, Berlin 1926.

- Geir Kjetsaa: Dostoyevsky . Heyne, 1993, ISBN 3-453-03530-5 (Norwegian: Fjodor Dostojevskij, et dikterliv . 1985. Translated by Astrid Arz).

- Konstantin Mochulsky: Dostoevsky . His Life and Work. Princeton University Press, 1967, ISBN 0-691-06027-4 (English, Russian: Достоевский: Жизнь и творчество . Paris 1947.).

- Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky . A Writer in His Time. Princeton University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-691-12819-1 (English, compact version of the 5-volume work).

- Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky , Princeton University Press .

5 volumes: The Seeds of Revolt, 1821–1849 . 1976, ISBN 0-86051-015-8 . ; The Years of Ordeal, 1850-1859 . 1983, ISBN 0-86051-242-8 . ; The Stir of Liberation, 1860-1865 . 1986 .; The Miraculous Years, 1865-1871 . 1995 .; The Mantle of the Prophet, 1871-1881 . 2002 (English). - Horst-Jürgen Gerigk: Dostoyevsky's development as a writer . From the “Dead House” to the “Karamazov Brothers”. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-596-90558-4 .

Religion and philosophy

In German language:

- Nikolai Berdjajew : Dostoyevsky's worldview . CH Becksche, Munich 1924 (Russian: Миросозерцание Достоевского .).

- Maximilian Braun : Dostoevsky . The complete work as diversity and unity. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1976, ISBN 3-525-01210-1 .

- Eugen Drewermann : That even the very lowest is my brother . Dostoevsky - poet of humanity. Walter Verlag, Zurich 1998, ISBN 3-530-40048-3 .

- Fedor Stepun : Dostoevsky . Weltschauung and Weltanschauung. Carl Pfeffer Verlag, Heidelberg 1950.

- Frank Thiess : Dostoevsky . Realism on the verge of transcendence. Seewald Verlag, Stuttgart 1971.

English:

- Wil van den Bercken: Christian Fiction and Religious Realism in the Novels of Dostoevsky . Anthem Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0-85728-976-6 (English).

- Steven Cassedy: Dostoevsky's Religion . Stanford University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-8047-5137-7 (English).

- George Pattison, Diane Oenning Thompson (Eds.): Dostoevsky and the Christian Tradition . Cambridge University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-521-78278-4 (English).

- James Patrick Scanlan: Dostoevsky the Thinker . Cornell University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-8014-7670-9 (English).

- Rowan Williams : Dostoevsky, Language, Faith and Fiction . Baylor University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-1-84706-425-7 (English).

- René Girard : Resurrection From The Underground: Feodor Dostoevsky . The Crossroad Publishing Company, New York 1997, ISBN 0-8245-1608-7 (English).

Literary perspective

- Mikhail Bakhtin : Problems of Dostoyevsky's Poetics . Ullstein, 1988, ISBN 3-548-35228-6 . , first in 1929

- Rudolf Neuhäuser: Fyodor M. Dostojewskij . Life - work - effect. 15 essays. Böhlau, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-205-78925-3 .

- Malcolm V. Jones, Garth M. Terry: New essays on Dostoyevsky . Cambridge University Press, 2010 (English).

- Rudolf Neuhäuser: FM Dostojevskij: The great novels and stories . Interpretations and analyzes. Böhlau, Vienna, Cologne, Weimar 1993, ISBN 3-205-98112-X .

Reception and effect

- Olga Caspers: A Writer at the Service of Ideology . To the Dostoevskij reception in the Soviet Union. Otto Sagner, Munich, Berlin, Washington DC 2012, ISBN 978-3-86688-159-4 .

- Horst-Jürgen Gerigk: Dostoyevsky, the tricky Russian . The history of its impact in the German-speaking area. Attempto, Tübingen 2000.

- Hans Rothe (Ed.): Dostojevskij and the literature . Lectures on the 100th year of death of the poet at the 3rd international conference of the "Slavenkommitee" in Munich. Böhlau, Cologne Vienna 1983, ISBN 3-412-10882-0 , p. 505 .

- Horst-Jürgen Gerigk: A master from Russia . Relationship fields of the effect of Dostoyevsky. Fourteen essays. Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2010, ISBN 978-3-8253-5782-5 .

Dostoevsky in literature and film

Many novels, fiction and television films have the life of Dostoyevsky on the subject:

Novels

- Alja Rachmanowa: The Life of a Great Sinner . A Dostoevsky novel. Benziger, Einsiedeln, Zurich 1947.

- Elfriede Hashagen: The invisible sky . Dostoevsky in Siberia. Eugen Salzer, Heilbronn 1951.

- Stanisław Mackiewicz : the player of his life . Thomas, Zurich 1952.

- Erich Fabian: In the storm . Hinstorff, Rostock 1961.

- Eva Marianne Saemann: The passionate one . Dostoyevsky's novel of life. Bertelsmann, Gütersloh 1961.

- Stephen Coulter: Dostoyevsky . A tragic life. Diana, Constance, Stuttgart 1962.

- Erich Fabian: The doppelganger . A Dostoevsky novel. Hinstorff, Rostock 1964.

- Dora Bregova: Conspiracy in St. Petersburg . Dostoevsky novel 1821–1849. Verlag der Nation, Berlin 1967.

- Dora Bregowa: The Way of the Damned . Dostoevsky novel 1950–1959. Verlag der Nation, Berlin 1978.

- Hasso Laudon: The Eternal Heretic . A Dostoevsky novel. 2nd Edition. The Morning, 1982, ISBN 3-371-00160-1 .

- JM Coetzee : The Master of Petersburg . S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-10-010809-4 . German by Wolfgang Krege (Original edition: The Master of Petersburg , first published in 1994)

- Leonid Zypkin : A summer in Baden-Baden . Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-8270-0488-8 . Translated from the Russian by Alfred Frank

Feature and television films

- FMD - Psychogram of a player (TV film), FRG 1971, director: Georg Tressler , with Paul Albert Krumm

- Un amore di Dostoevskij (multi-part television film), Italy 1978, directed by Alessandro Cane

- 26 Days from the Life of Dostoyevsky , USSR 1981, directed by Alexander Sarchi

- Une Saison dans la vie de Fedor Dostoïevski (TV film), France 1981, directed by Guy Jorré , with Marcel Bozzuffi

- The Gambler , USA 1997, directed by Károly Makk , with Michael Gambon

- Dug iz Baden - Badena (TV film), Serbia 2000, directed by Slobodan Z. Jovanovic

- I demoni di San Pietroburgo , Italy 2008, directed by Giuliano Montaldo

- Dostoevsky (TV series), Russia 2010, director: Wladimir Chotinenko, with Yevgeny Mironov

Comic and graphic novel

- Vitali Konstantinov: FMD. The life and work of Dostoevsky. Knesebeck, Munich 2016.

Web links

German-language pages

- www.dostojewski.eu Extensive site on life and work

- Orest Miller: On Dostoyevsky's life story

- https://volltext.net/texte/fjodor-dostojewskij-nikolaj-olejnikow- Zwischen-tiefsinn-und-nonsense/

In other languages

- FyodorDostoevsky.com life and work, essays, pictures, book tips, links and discussion forum (English)

- Christiaan Stange's Dostoevsky Research Station life and work, bibliography, links, citations (English)

- Research tools the University of Illinois (English)

- Literature by and about Fyodor Michailowitsch Dostojewski in the bibliographic database WorldCat

Fonts on the net

- Literature by and about Fyodor Michailowitsch Dostojewski in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Fjodor Michailowitsch Dostojewski in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Fyodor Michailowitsch Dostojewski in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Autobiographical writings

- Works by Fyodor Michailowitsch Dostojewski in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Collection of literary writings

Remarks

- ↑ All dates in this article are based on the Gregorian calendar unless otherwise noted .

-

↑ Reinhard Lauer : History of Russian Literature. From 1700 to the present . CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-50267-9 , p. 365 . Stefan Zweig: Three masters. Balzac - Dickens - Dostoevsky . Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1922, p.

113 ( limited online version in Google Book search). Steven G. Marks: How Russia Shaped the Modern World. From Art to Anti-Semitism, Ballet to Bolshevism . Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ 2003, ISBN 0-691-09684-8 , pp.

100 ( books.google.de ). - ↑ Geir Kjetsaa: Dostojewskij: convict - player - poet prince . VMA, Wiesbaden 1992, ISBN 978-3-928127-02-8 , foreword.

- ↑ Anton Seljak: Ivan Turgenev economies . A writer's existence between aristocracy, artistry and commerce. Pano, Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-907576-65-9 .

-

↑ Andreas Guski: "Money is shaped freedom" - paradoxes of money in Dostoevskij . In: Dostoevsky Studies . tape 16 . Narr, 2012, ISSN 1013-2309 , p. 7-57 . Christian Kühn: Dostoyevsky and money . In: German Dostoyevsky Society . tape

11 . Clasen, 2004, ISSN 1437-5265 , p. 111-138 . - ^ Dostoevsky . In: Enzyklo.de German encyclopedia . Retrieved September 17, 2014.

-

↑ Andreas Kappeler: Russia as a multi-ethnic empire: emergence - history - decay , p. 72.

Neil Heims: Biography of Fyodor Dostoevsky . In: Fyodor Dostoevsky . Chelsea House, Langhorne, Pennsylvania 2005, ISBN 0-7910-8117-6 , pp. 9 f . ( limited online version in Google Book Search - USA ). Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 , pp.

108 . Detailed information on Dostoyevsky's genealogy is available on the website: Fyodor Michailowitsch Dostojewski bei Rodovid. Retrieved December 11, 2013 .

- ^ Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 , pp. 106 f .

- ^ Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 , pp. 80 f., 108 .

- ^ Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 , pp. 108 .

-

^ Konstantin Mochulsky: Dostoevsky. His Life and Work . Princeton University Press, 1967, ISBN 0-691-06027-4 , pp. 8 ( limited online version in Google Book Search). Neil Heims: Biography of Fyodor Dostoevsky . In: Fyodor Dostoevsky . Chelsea House, Langhorne, Pennsylvania 2005, ISBN 0-7910-8117-6 , pp.

10 . -

^ Victor Terras: The Art of Crime and Punishment . In: Harold Bloom (Ed.): Fyodor Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment . Chelsea House / Infobase Publishing, New York 2004, ISBN 0-7910-7579-6 , pp. 275 . Katya Tolstaya: Kaleidoscope. FM Dostoevsky and the Early Dialectical Theology . Brill, 2013, ISBN 978-90-04-24458-0 , pp.

50 ( limited online version in Google Book search). Bruce Kinsey Ward: Dostoyevsky's Critique of the West. The Quest for the Earthly Paradise . Wilfrid Laurier University Press, Waterloo, Ontario 1986, ISBN 0-88920-190-0 , pp.

16 ( limited online version in Google Book search). Robert L. Belknap: The Genesis of The Brothers Karamazov. The Aesthetics, Ideology, and Psychology of Making a Text . Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Illinois 1990, ISBN 0-8101-0845-3 , pp.

19 ( limited online version in Google Book search). - ↑ Katya Tolstaya: Kaleidoscope. FM Dostoevsky and the Early Dialectical Theology . Brill, 2013, ISBN 978-90-04-24458-0 , pp. 50 .

- ^ Konstantin Mochulsky: Dostoevsky. His Life and Work . Princeton University Press, 1967, ISBN 0-691-06027-4 , pp. 9 f .

- ↑ Bruce Kinsey Ward: Dostoyevsky's Critique of the West. The Quest for the Earthly Paradise . Wilfrid Laurier University Press, Waterloo, Ontario 1986, ISBN 0-88920-190-0 , pp. 16 .

- ^ Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky. The Seeds of Revolt, 1821-1849 . Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1976, ISBN 0-691-06260-9 , pp. 33 ( limited online version in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b c Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 , pp. xviii .

-

^ Donald W. Treadgold: The West in Russia and China. Religious and Secular Thought in Modern Times. Volume 1: Russia 1472-1917 . Cambridge University Press, London, New York 1973, ISBN 0-521-08552-7 , pp. 203 ( limited online version in Google Book Search). Konstantin Mochulsky: Dostoevsky. His Life and Work . Princeton University Press, 1967, ISBN 0-691-06027-4 , pp.

10 f . -

^ Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky. The Seeds of Revolt, 1821-1849 . Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1976, ISBN 0-691-06260-9 , pp. 127 . Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 , pp.

1 . -

^ Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky. The Seeds of Revolt, 1821-1849 . Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1976, ISBN 0-691-06260-9 , pp. 130 . Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky. A Writer in His Time . Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 2010, ISBN 978-0-691-12819-1 , pp.

72 . Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 , pp.

382 . -

↑ Christiane Schulz: "I learned Schiller by heart" - the "spiritual ferment" Schiller in Dostoyevsky's short story . In: Yearbook of the German Dostoyevsky Society . Yearbook 17, 2010, ISSN 1437-5265 , p. 10-41 . Konstantin Mochulsky: Dostoevsky. His Life and Work . Princeton University Press, 1967, ISBN 0-691-06027-4 , pp.

14 . On Dostoyevsky's Schiller reception: Michael Wegner: Fedor Dostoevsky and Friedrich Schiller . In: Michael Wegner (ed.): Heritage and obligation. On the international impact of Russian and Soviet literature in the 19th and 20th centuries . Schiller University, Jena 1985.

- ^ Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 , pp. 109 .

- ^ Andrei Dostoevsky: The Father's Death . In: Peter Sekirin (Ed.): The Dostoevsky Archive - Firsthand Accounts of the Novelist from Contemporaries' Memoirs and Rare Periodicals . 1997, p. 60 .

-

^ Sigmund Freud: Dostojewski and the killing of the father. In: The original figure of the Karamasoff brothers. Dostoyevsky's sources, drafts and fragments. Piper-Verlag, Munich 1928, p. XIX.

see also Fritz Schmidl: Freud and Dostoevsky . In: Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association . tape 13 , 1965, p. 518-532 . Joseph Frank: Freud's Case History of Dostoevsky . In: Through the Russian Prism - Essays on Literature and Culture . Princeton, New Jersey 1990, pp.

109-121 . -

↑ End of trauma. Retrieved December 6, 2013 . Der Spiegel, July 14, 1975

Karel van het Reve: Dr. Freud and Sherlock Holmes . Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1994. Review: Reve, Karel van het: Dr. Freud and Sherlock Holmes. Retrieved December 6, 2013 . Maike Schult: Tempting father killing - Freud's fantasies about Dostoyevsky . In: Yearbook of the German Dostoyevsky Society . tape

10 , 2003, ISSN 1437-5265 , p. 44-55 . Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky. The Seeds of Revolt, 1821-1849 . Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1976, ISBN 0-691-06260-9 , pp.

80 . - ^ Robert Bird: Fyodor Dostoevsky . Reaction Books, London 2012, ISBN 978-1-86189-900-2 , pp. 21 ( limited online version in Google Book search).

- ↑ see in particular Letter 107 of March 24, 1856, in German in: Friedr. Hitzler (Ed.): Collected Letters 1833–1881 . Piper, Munich 1966.

- ^ Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 , pp. 3 .

- ^ Robert Bird: Fyodor Dostoevsky . Reaction Books, London 2012, ISBN 978-1-86189-900-2 , pp. 22 .

- ^ Julian W. Connolly: Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov . Bloomsbury, New York / London 2013, ISBN 978-1-4411-0847-0 , pp. 2 ( limited online version in Google Book Search).

-

^ Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky. The Seeds of Revolt, 1821-1849 . Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1976, ISBN 0-691-06260-9 , pp. 127 . Konstantin Mochulsky: Dostoevsky. His Life and Work . Princeton University Press, 1967, ISBN 0-691-06027-4 , pp.

22 . - ^ Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky. The Seeds of Revolt, 1821-1849 . Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1976, ISBN 0-691-06260-9 , pp. 137 ff .

- ^ Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Press, 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 , pp. 303 ( limited online version in Google Book search).

- ^ Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky. The Seeds of Revolt, 1821-1849 . Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1976, ISBN 0-691-06260-9 , pp. 159 .

- ^ Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky. The Stir of Liberation, 1860-1865 . Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1986, ISBN 0-691-01452-3 , pp. 67 ( limited online version in Google Book search).

-

↑ Malcolm Jones: Dostoevsky and the Dynamics of Religious Experience . Anthem Press, London 2005, ISBN 1-84331-205-0 , pp. 4 ( limited online version in Google Book Search). Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Press, 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 , pp.

32-38 . - ^ Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky. The Seeds of Revolt, 1821-1849 . Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1976, ISBN 0-691-06260-9 , pp. 175 .

- ^ Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky. A Writer in His Time . Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 2010, ISBN 978-0-691-12819-1 , pp. 89 ( limited online version in Google Book search).

-

^ Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Press, 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 , pp. 31 f . Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky. The Seeds of Revolt, 1821-1849 . Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1976, ISBN 0-691-06260-9 , pp.

206 ff . -

^ Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Press, 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 , pp. 310 ff . Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky. The Seeds of Revolt, 1821-1849 . Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1976, ISBN 0-691-06260-9 , pp.

239 ff . - ^ Konstantin Mochulsky: Dostoevsky. His Life and Work . Princeton University Press, 1967, ISBN 0-691-06027-4 , pp. 40-139 .

- ^ William Mills Todd: Dostoevsky as a Professional Writer . In: W. J. Leatherbarrow (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Dostoevskii . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2002, ISBN 0-521-65253-7 , pp. 75 ( limited online version in Google Book Search - USA ).

- ^ Konstantin Mochulsky: Dostoevsky. His Life and Work . Princeton University Press, 1967, ISBN 0-691-06027-4 , pp. 133 .

- ^ Philip S. Taylor: Anton Rubinstein. A Life in Music . Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana 2007, ISBN 0-253-34871-4 , pp. 24 ( limited online version in Google Book search).

- ↑ André Gide: Dostoievsky . Telegraph Books, 1981, ISBN 0-89760-319-2 , pp. 29 ( books.google.de ).

-

↑ Reinhard Lauer: History of Russian Literature. From 1700 to the present . C. H. Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-50267-9 , pp. 365 . Socialist Circle, Arrest and Investigation, 1846-1849 . In: Peter Sekirin (Ed.): The Dostoevsky Archive. Firsthand Accounts of the Novelist from Contemporaries' Memoirs and Rare Periodicals . McFarland, Jefferson, North Carolina 1997, ISBN 0-7864-0264-4 , pp.

77 f . ( limited online version in Google Book Search - USA ). - ^ Kenneth A. Lantz: The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia . Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut 2004, ISBN 0-313-30384-3 , pp. 245 .

-

^ Neil Heims: Biography of Fyodor Dostoevsky . In: Fyodor Dostoevsky . Chelsea House, Langhorne, Pennsylvania 2005, ISBN 0-7910-8117-6 , pp. 7 f . Wording of the letter: VG Belinsky 1847: Letter to NV Gogol. Retrieved November 19, 2013 .

-

^ Joseph Frank: Dostoevsky. A Writer in His Time . Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 2010, ISBN 978-0-691-12819-1 , pp. 173 . Nikolai Beltischikow: Dostoyevsky in the Petraschewzen trial . Reclam, 1977, p.

206 . Wording: "The military tribunal has therefore sentenced the engineer-lieutenant ... to death with the removal of his military rank and all property rights ..." -

↑ On the mock execution see the report of fellow prisoner Dmitri Dmitrowitsch Ascharumow: Memoirs . In: North and South . 1902, p. 70, 361 . See also Letter # 88 Dostoyevsky to his brother Michail of December 22, 1849: Friedr. Hitzer (Ed.): Dostojewski. Collected Letters 1833–1881 . Piper, Munich 1966.

-