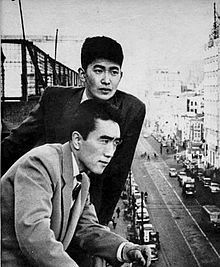

Mishima Yukio

Mishima Yukio ( Japanese 三島 由 紀 夫 ; in German Yukio Mishima ; born January 14, 1925 in Tokyo as Hiraoka Kimitake ( 平 岡 公 威 ); † November 25, 1970 ibid) was a Japanese writer, poet , director and nationalist political activist. Mishima wrote novels , screenplays , plays , short stories as well as poetry and a libretto and is considered one of the most important authors of the 20th century . His avant-garde works mixed modern with traditional aesthetics and, with their focus on taboo topics such as sexuality , death , violence and political change, broke various cultural norms of their time.

In addition to his work as a contemporary author of Japanese post-war literature, Mishima was also active as a political activist and in this context founded his private militia, the Tatenokai . On November 25, 1970, he and three members of his militia carried out an attempted coup on the Japanese military base with the aim of restoring the emperor's power. After this failed, Mishima committed ritual suicide . The coup later became known around the world as the "Mishima Incident".

The Mishima Prize was introduced in 1988 to honor his life's work and has been awarded annually since then.

Life

Early years

Mishima was born under the name Hiraoka Kimitake, the son of Hiraoka Azusa, Deputy for the Ministry of Fisheries in the Ministry of Agriculture, and Hiraoka Shizue (nee Hara). Shizue's father, Kenzō Hashi, was a scholar in Chinese literature and had served with his family in the Maeda samurai clan for generations . Mishima also had a brother named Chiyuki and a sister named Mitsuko, who died of typhus in 1945 at the age of 17 .

His early childhood was strongly influenced by his grandmother Natsuko, who separated Mishima from his family for several years and aroused his interest in kabuki theater. Natsuko is the daughter of Matsudaira Yoritaka, a daimyo from Hitachi Province , and was raised under Arisugawa Taruhito in the Japanese imperial family. Even after she moved out of the imperial house and married Sadatarō Hiraoka, a bureaucrat and general of Karafuto Prefecture , she retained her aristocratic claims and violent tendencies from upbringing, both of which would have a great influence on Mishima's later literature. Natsu banned Mishima from exercising and socializing with other boys his age, so he spent a lot of time alone or with his cousins.

At the age of twelve, Mishima returned to his family and developed a close relationship with his mother. His father, however, drilled him with military discipline and ridiculed his devotion to literature as "effeminate". Among other things, he is said to have checked his room regularly for manuscripts and subsequently violently maltreated Mishima, so that Mishima began to hide his texts or to tear them up.

School time and first works

When he was six, Mishima attended Gakushuin , an elite state school where he belonged to a literary society. He owed this to his grandmother, who insisted that he attend this school, while his parents were rather negative about it. Inspired by Oscar Wilde , Rainer Maria Rilke , Raymond Radiguet and a large number of Japanese authors, at the age of twelve he wrote his first own texts not only in Japanese , but also in French , German and English , which he had taught himself by himself. In the same year he became a member of the editorial board of his literary association and thus the youngest member in the history of the school. There he first became aware of the works of the Japanese author Michizō Tachihara , for whom he developed a great affinity and subsequently adapted his writing style, Waka . In the following years Mishima published his texts exclusively in Waka before he took up the prose .

At the age of thirteen, Mishima was asked by his school to write a short story for the student magazine, whereupon he submitted Hanazakari no Mori ( The forest in bloom ), a story about a boy who feels that his ancestors are in his Body, and blames this for its internal turmoil. Mishima's teachers were so enthusiastic that they passed the short story on to the renowned literary magazine Bungei-Bunka , which had it printed in a limited edition of 4,000 copies. In order to avoid bullying by his schoolmates, the story was published under the pseudonym Yukio Mishima, which he then used for all of his literary works.

Mishima's short story Tabako (Eng. The Cigarette ), published in 1946, dealt specifically with the bullying he was exposed to after telling his schoolmates in rugby union that he was going to join the literary association. The trauma is also considered the inspiration for his 1954 published short story Shi o Kaku Shōnen (Eng. The boy who wrote history ).

Since Mishima feigned tuberculosis when he was drafted, he did not have to do military service during World War II . He left the University of Tokyo in 1947 with a degree in law and worked in the Ministry of Finance , but announced within a year in order to have more time for writing.

Post war literature

At the beginning of his career as a full-time author, Mishima made a name for himself in particular as a playwright for the Kabuki theater, for which he modernized traditional Nō plays . The drama Kemono no tawamure (dt. The joke of the beasts ), for example, is a parody on Motomezuka represents a well-known drama from the 14th century. Through his successful short story Misaki nite no Monogatari (Eng. A story on the Cape ), the Japanese novelist Yasunari Kawabata became aware of him, whom he visited in January 1946 to get advice on his manuscripts Chūsei and Tabako . The latter was published with the help of Kawabata in the literary magazine Ningen , which also enabled him to publish his first novel Tōzoku ( Eng . Thieves ).

At the end of the same year, Mishima began work on Tōzoku , a story about two aristocrats who develop a fascination for suicide . It was first published in 1948, officially counting Mishima in the ranks of the second generation of post-war poets. The first major success followed the following year with the publication of his second novel Confessions of a Mask , a semi- autobiographical story about a boy who discovered his homosexuality and kept it a secret in order not to be expelled from society. The novel was very successful internationally and made Mishima famous at the young age of 24. In response, a series of essays followed in Kindai Bungaku magazine , addressed to his mentor Yasunari Kawabata as thanks.

Due to its increasing popularity, Mishima traveled frequently from 1950 and got to know foreign cultures, which he incorporated into his work from the beginning of the 1950s. In 1952 he lived in Greece for a few months and meticulously studied Greek mythology . His novel The Sound of Waves deals with some of the experiences of the trip and was largely inspired by the Greek saga of Daphnis and Chloe .

From the mid-1950s onwards, Mishima treated more and more contemporary events in his works. The temple fire, for example, is a fictionalization of the events and inner thoughts of a monk who develops an obsession with a golden hall in the temple precinct and ultimately burns it down. The novel is based on an actual incident: On July 2, 1950, the Golden Pavilion of the Rehgarten Temple in Kyoto was destroyed by the arson of a monk. Mishima had visited the perpetrator in prison for research. After the banquet , an affair between a reformist and the owner of a nightclub in Ginza is dealt with and has many parallels to the adultery of the Japanese diplomat Arita Hachirō . He then sued Mishima for violating his right to privacy and was awarded 800,000 yen as compensation after three years of litigation .

His last completed work was the four-part novel cycle The Sea of Fertility ; it is Mishima's answer to the increasing influence of Western values on Japanese culture and deals with central topics such as the teaching of Alaya consciousness and the relationships between youth, beauty, reason and knowledge. The resulting philosophy was subsequently named “cosmic nihilism” and forms the basis for Mishima's worldview and political activism, which he practiced in parallel. The last volume of the tetralogy, The Angel's Death Marks , was published post mortem in 1971 after the manuscript was found in his apartment.

Mishima was nominated three times for the Nobel Prize for Literature , but did not win it despite being three times favorite. Mishima himself expressed no surprise and reported that a Japanese author had already received the award in 1968 and that his chances were therefore slim.

Acting and modeling career

In the 1960s Mishima also appeared in a number of lurid Yakuza and Samurai films and posed for photo books with homoerotic half-nudes of himself. With Yūkoku ( 憂国 , 1966), he directed a film in the Noo style based on his eponymous story (German Patriotism ) based. In it, Mishima plays the naval officer Takeyama, who after the failed coup on February 26, 1936, says goodbye to his wife Reiko and commits seppuku (ritualized suicide). His wife follows him to death.

Political activism

After 1960, given the left student unrest in Tokyo, Mishima turned increasingly to nationalist ideas. In his essay Bunka Bōeiron ( 文化 防衛 論 , German "defense of a culture") Mishima argued in 1968 that the Tennō , the emperor of Japan, was the source of Japanese culture and the defense of the emperor was thus also a defense of one's own culture. He formed an approximately 80-strong private army, the Tatenokai (“shield society”), which was mainly recruited from right-wing student circles and dedicated itself to fighting communism and protecting traditional Japanese values and the emperor. He also called for a nuclear armament in Japan.

Coup attempt and death

On November 25, 1970, Mishima and four members of the Tatenokai took the duty commander of the Japanese armed forces hostage in Tokyo . From the balcony of the headquarters (today the seat of the Japanese Ministry of Defense ) he gave a speech in which he called on the army to occupy the parliament and to reinstate the emperor. However, due to the soldiers' disinterest, his appeal had no consequences. Immediately afterwards, Mishima and one of his close confidants committed seppuku and had themselves beheaded by a third person .

In a 1968 interview, Mishima said that, unlike the Western image of suicide , which is usually viewed as defeat, “hara-kiri sometimes lets you win”. According to Henry Scott Stokes' biography, Mishima had planned his suicide for several years and set the date of his death a year in advance. His belief in a chance of success with regard to the restoration of the empire therefore appears questionable. However, Stokes disagreed with views that Mishima's suicide was some sort of final artistic expression or a romantic double suicide with his lover. The setting - the center of the military force in Tokyo - makes the act a clearly politically motivated act.

Private life

Because of his weak stature, Mishima developed complexes regarding his body awareness at a young age, which is why he began excessive strength training from 1955 . He consistently carried out his routine of three weekly units for fifteen years until his death in 1970. In his essay Sun and Steel , published in 1968, he explored his motivations for weight training in more detail and lamented the habit of intellectuals to prioritize the mind and completely ignore the art and importance of the body. In addition to normal strength training, Kendo was later part of his repertoire.

After a brief engagement to Michiko Shōda , who would later marry the Emperor Akihito , Mishima married Yoko Sugiyama on June 11, 1958, with whom he had two children: a daughter named Noriko (born 1959) and a son named Ichiro (born 1958) . 1962).

Mishima hinted at signs of homosexuality in his first novels and visited gay bars in Japan while working on Forbidden Colors . The lack of clarity about Mishima's sexual orientation was an ongoing conflict between him and his wife, who until after his death denied that Mishima had ever had any interest in his own gender. In 1998, Japanese author Jiro Fukushima published a letter describing a sexual affair with Mishima that allegedly took place in 1951. His children then successfully sued Fukushima for omission.

Towards the end of his life, Mishima supported a very unique form of nationalism that made him hated by both the political left and conventional nationalists, the former especially because of his loyalty to the Bushidō , the samurai's code of honor , the latter because of his writing Bunka Bōeiron (dt .: "Defense of Culture"), in which he accused the then Emperor of Japan, Hirohito , of not having taken responsibility for the fallen Japanese soldiers in World War II .

family

Grandparents

- Grandfather: Sadatarō Hiraoka (1863–1942)

- Grandmother: Natsuko Hiraoka (1876–1939)

parents

- Father: Azusa Hiraoka (1894–1976)

- Mother: Shizue Hiraoka (1905–1987)

siblings

- Brother: Chiyuki Hiraoka (1930–1996)

- Sister: Mitsuko Hiraoka (1928–1945)

Other relatives

- Uncle: Hashira Hashi (1884–1936)

marriage

- Wife: Yoko Sugiyama (1937–1995)

- Daughter: Noriko Hiraoka (* 1959)

- Son: Ichiro Hiraoka (* 1962)

legacy

literature

The Shinchōsha publishing house, which publishes Mishima's books in Japan, renamed its annual literary prize in 1988 to the Mishima Prize .

His works Haru no Yuki , Kinkakuji , Rokumeikan and Shiosai were included in the UNESCO collection of representative works .

Movie

In 1958 Kon Ichikawa filmed Mishima's novel The Temple Fire as The Temple of the Golden Hall (Original: Enjō 炎 上 ).

Lewis John Carlino filmed Gogo no eikō in 1976 under the title The Way of All Flesh .

In 1985 the US-American director Paul Schrader made a film about Yukio Mishima's life called Mishima - A Life in Four Chapters . Although originally scheduled to participate in the Tokyo International Film Festival , Mishima was not included in the program because of threats from right-wing groups and objections from Mishima's widow who disliked the theming of Mishima's homosexuality. To date, the film has not been shown in Japanese cinemas.

In 1998 the film School of Desire was released, which is based on the novel Nikutai no gakkō (1963).

In 2012 the film started 11:25 Jiketsu no Hi: Mishima Yukio to Wakamonotachi ( 11 ・ 25 自決 の 日 三島 由 紀 夫 と 若 者 た ち ) by the Japanese director Kōji Wakamatsu about Mishima's attempted coup.

Musical arrangements

-

Gogo no eikō ( 午後 の 曳 航 )

- Editing: The betrayed sea (1986–1989; revised 1992). Musical drama in 2 acts. Libretto: Hans-Ulrich Treichel . Music: Hans Werner Henze . Premiere May 5, 1990 Berlin ( Deutsche Oper ). New version: Gogo No Eiko (2003; revised 2005). Premiere October 15, 2003 Tokyo (Suntory Hall). WP (revised version) August 26, 2006 Salzburg ( Festival )

-

Kinkakuji ( 金 閣 寺 )

- Opera in 3 acts (1976). Libretto : Claus H. Henneberg . Music: Toshirō Mayuzumi . Premiere June 23, 1976 Berlin ( Deutsche Oper )

politics

Since 1972, the right-wing Japanese group Issuikai, together with other right-wing extremist groups, has held an annual heroes' memorial meeting at the Mishima Tomb.

Works (selection)

Novels

- 1948 Tōzoku ( 盗賊 , German thieves )

- 1949 Kamen no Kokuhaku ( 仮 面 の 告白 )

- Confession of a mask . German translation from English by Helmut Hilzheimer, Rowohlt Verlag GmbH, 1964. ISBN 3-499-15652-0 .

- Confessions of a Mask. German direct translation from Japanese by Nora Bierich, Kein & Aber , 2018. ISBN 978-3036957845 .

- 1950 Ai no kawaki ( 愛 の 渇 き )

- Thirst for love . German translation by Josef Bohaczek, Frankfurt: Insel Verlag, 2000. ISBN 3-458-17010-3 .

- 1950 Ao no jidai ( 青 の 時代 )

- 1950 Jumpaku no yoru ( 純白 の 夜 )

- 1951 Natsuko no bōken ( 夏 子 の 冒 険 )

- 1951–1953 Kinjiki ( 禁 色 )

- Forbidden Colors . English translation by Alfred H. Marks, Secker & Warburg , 1968 (Volume 1), Berkley Publishing, 1974 (Volume 2). ( see also: Butō )

- 1953 Nippon-sei ( に っ ぽ ん 製 )

- 1953 Shiosai ( 潮 騒 )

- The surf . Translation by Gerda von Uslar and Oscar Benl, Rowohlt Verlag, Hamburg, 1959

- The Sound of Waves . English translation by Meredith Weatherby, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1956

- 1956 Kōfukugō Shuppan ( 幸福 号 出 帆 )

- 1956 Kinkakuji ( 金 閣 寺 )

- The temple fire . List, Munich, 1961 ( see also: Kinkaku-ji )

- The Golden Pavilion. Translated from the Japanese by Ursula Gräfe. No & But, Zurich 2019, ISBN 978-3-0369-5807-1

- 1957 Bitoku no yorumeki ( 美 徳 の よ ろ め き )

- 1958–1959 Kyōko no ie ( 鏡子 の 家 )

- 1960 Ojōsan ( お 嬢 さ ん )

- 1962 Utsukushii hoshi ( 美 し い 星 )

- 1963 Ai no shissō ( 愛 の 疾走 )

- 1963 Gogo no eikō ( 午後 の 曳 航 )

- The sailor who betrayed the sea . Translation by Sachiko Yatsushiro, 1970

- The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea . English translation by John Nathan, Alfred A. Knopf, 1965.

- 1963 Nikutai no gakko ( 肉体 の 学校 )

- 1964 Kinu to meisatsu ( 絹 と 明察 )

- 1966 Fukuzatsu na kare ( 複 雑 な 彼 )

- 1966 Yakaifuku ( 夜 会 服 )

- 1967 Utage no Ato ( 宴 の あ と )

- After the banquet . Translation by Sachiko Yatsushiro, Reinbek, Rowohlt, 1967.

- 1965–1970 Hōjō no umi ( 豊 饒 の 海 ), German: The sea of fertility , consisting of the four novels:

- Haru no Yuki ( 春 の 雪 ), snow in spring . German translation from Japanese by Siegfried Schaarschmidt . Munich :, Hanser 1985. ISBN 3-446-14395-5

- Homba ( 奔馬 ), under the storm god . German translation from Japanese by Siegfried Schaarschmidt. Munich: Hanser 1986. ISBN 3-446-14628-8

- Akatsuki no Tera ( 暁 の 寺 ), The Temple of Dawn . German translation from Japanese by Siegfried Schaarschmidt, Munich: Hanser, 1987. ISBN 3-446-14614-8

- Tennin Gosui ( 天人 五 衰 ), The Angel's Death Marks . German translation from Japanese by Siegfried Schaarschmidt. Munich: Hanser, 1988. ISBN 3-446-14615-6

stories

- 1938 Sukampo ( 酸模 )

- 1940 Damiegarasu ( 彩 絵 硝 子 )

- 1941 Hanazakari no mori ( 花 ざ か り の 森 , The forest in full bloom )

- 1942 Ottō to maya ( 苧 菟 と 瑪耶 )

- 1943 Daidai ni zansan ( 世 々 に 残 さ ん )

- 1944 Yoru no kuruma ( 夜 の 車 ), later renamed ( 中 世 に 於 け る 一 殺人 常 習 者 の 遺 せ る 哲学 的 日記 の 抜 粋 )

- 1945 Esgai no kari ( エ ス ガ イ の 狩 )

- 1946 Tobacco ( 煙草 )

- 1947 Yoru no shitaku ( 夜 の 仕 度 , German preparation for the night )

- 1949 Magun no tsūka ( 魔 群 の 通過 )

- 1949 Hōseki Baibai ( 宝石 売 買 ).

- 1953 Radige no shi ( ラ デ ィ ゲ の 死 )

- 1961 Yūkoku ( 憂国 )

- 1966 Eirei no sei ( 英 霊 の 聲 )

- 1969 Ranryō'ō ( 蘭陵王 )

Stage works

- 1948 Shishi ( 獅子 ). After Euripides Medea.

- 1956 Rokumeikan ( 鹿鳴 館 )

- 1956 Kindai nōgakushū ( 近代 能 楽 集 )

- Five modern Nō games . German published in 1962 as Rowohlt Paperback paperback with the title Six modern no-games (the piece Die Damasttrommel from 1953 was included). Based on the version by Donald Keene, translated by Gerda v. Uslar from English, contains the pieces:

- Kantan ( 邯鄲 , The dream pillow)

- Aya no tsuzumi ( 綾 の 鼓 , The damask drum)

- Sotoba komachi ( 卒 塔 婆 小 町 , The Hundredth Night)

- Aoi no ue ( 葵 上 , The Lady Aoi)

- Hanjo ( 班 女 , The exchanged fans)

- Dōjōji ( 道 成 寺 , face in the mirror)

- Yuya ( 熊 野 )

- Yoroboshi ( 弱 法師 )

- 1958 Shōbi to kaizoku ( 薔薇 と 海賊 )

- 1960 Nettaiki ( 熱 帯 樹 )

- 1961 Tōka no kiku ( 十 日 の 菊 )

- 1965 Sado kōsaku bujin ( サ ド 侯爵夫人 ) (Madame de Sade), translated into English by Donald Keene ; from English to German transl. by Elisabeth Plessen

- 1966 Sei Sebastian no junkyō ( 聖 セ バ ス テ ィ ア ン の 殉教 ) [Translation by Gabriele D'Annunzio's Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien , together with Ikeda Kōtarō 池田 弘太郎 ]

- 1967 Suzakuke no metsubō ( 朱雀 家 の 滅亡 )

- 1968 Waga tomo Hitler ( わ が 友 ヒ ッ ト ラ ー )

- 1969 Chinsetsu yumiharizuki ( 椿 説 弓 張 月 , 3 acts, 8 lifts, adaptation of a work by Kyokutei Bakin for the Kabuki )

Reviews and mishaps

- 1955 Shōsetsuka no kyūka ( 小説家 の 休 暇 )

- 1958–1959 Fudōtoku kyōiku kōza ( 不 道 徳 教育 講座 )

- 1960 Ratai to ishō ( 裸体 と 衣裳 )

- 1964 Watashi no henreki jidai ( 私 の 遍 歴 時代 )

- 1967 Taiyō to tetsu ( 太陽 と 鉄 )

- Sun and Steel . English translation by John Bester, Kodansha International, Tokyo, 1968. ISBN 4-7700-2903-9 .

- 1967 Hagakure Nyūmon ( 葉 隠 入門 )

- To an ethic of action. Introduction to the Hagakure . Hanser Verlag, 1987.

- 1968 Bunka bōeiron ( 文化 防衛 論 )

Others

- 1947 Misaki nite no mongatari ( 岬 に て の 物語 , A story at the Cape )

- 橋 づ く し , ( Hashizukushi , The Seven Bridges), 1958. Published in the Merian Tokyo edition of February 2, 1972, No. 2 / XXV

- The boy who wrote poetry [or The boy who wrote poetry ]. Short story. Strictly limited and authorized edition with lithographs by Arno Breker , Bonn 1976.

- Yukio Mishima: Collected Stories. Rowohlt, 1971. ISBN 3-498-09280-4

- Yukio Mishima三島由紀夫: The boy who writes poetry (The Boy who writes poetry). Translation by Beate von Kessel, editor Marco J. Bodenstein. Marco-Edition Bonn-Berlin-New York, 2010. ISBN 978-3-921754-48-1

literature

-

Barakei (Killed by Roses). Photos by Eikoh Hosoe , Shueisha, Tokyo, 1963. Foreword and model: Yukio Mishima.

- New edition 1984: Ba * ra * kei - Ordeal by Roses: Photographs of Yukio Mishima , with an afterword by Mark Holborn. Aperture, New York City, ISBN 0-89381-169-6 .

- Hijiya-Kirschnereit , Irmela: Mishimas Yukios novel Kyoko-no ie. Attempt an intratextual analysis. Verlag Otto Harrassowitz, 1976. ISBN 3-447-01788-0 .

- Nagisa Oshima: The premonition of freedom. It has a good essay on Yukio Mishima: Mishima, or The Geometric Place of Lack of Political Consciousness. Verlag Klaus Wagenbach, 1982. ISBN 3-8031-3511-7 .

- Marguerite Yourcenar : Mishima or the vision of emptiness , French 1980, German Munich, 1985

- Hans Eppendorfer : The Magnolia Emperor: Thinking about Yukio Mishima. Reinbek: Rowohlt, 1987

- Hijiya-Kirschnereit, Irmela: What does understanding Japanese literature mean? There is a chapter in the book: Thomas Mann's novella Death in Venice and Mishima Yukio's novel Kinjiki. A comparison. edition suhrkamp, 1990. ISBN 3-518-11608-8 .

- Roy Starrs: Deadly Dialectics: Sex, Violence, and Nihilism in the World of Yukio Mishima, University of Hawaii Press, 1994

- Lisette Gebhardt / Uwe Schmitt : Mishima is back. Report on the discovery of previously unknown texts by the author Yukio Mishima. ("Mishima no ikai karano kikan"), Tōkyō 1996

- Jerry S. Piven: The madness and perversion of Yukio Mishima. Westport, Conn. : Praeger, 2004

- Henry Scott-Stokes: The life and death of Yukio Mishima. New York, First print 1974. German edition 1986. Goldmann Verlag ISBN 3-442-08585-3 : Yukio Mishima. Life and death.

- Александр Чанцев: Бунт красоты. Эстетика Юкио Мисимы и Эдуарда Лимонова. Москва: Аграф 2009. ISBN 978-5-7784-0386-4 .

- Rebecca Mak: Mishima Yukio's “In Defense of Our Culture” (Bunka bōeiron). A Japanese identity discourse in an international context. Berlin / Boston: De Gruyter 2014. ISBN 978-3-11-035317-4 .

See also

Web links

- Literature by and about Mishima Yukio in the catalog of the German National Library

- Yukio Mishima in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Fritz J. Raddatz : Dying is culture ( portrait in the period 48/2000 )

- The German Poetry Library Poem in honor of Mishima

- When Yukio Mishima was a samurai warrior

Individual evidence

- ^ Mishima Yukio essay

- ↑ Naoki Inose & Hiroaki Sato, Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima (Naoki Inose, Hiroaki Sato) (Stone Bridge Pr 2012)

- ↑ Yukio, Mishima in the web archive ( Memento from February 21, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c The Strange Case of Yukio Mishima , BBC documentary , Great Britain 1985.

- ^ The bloody work , article from July 28, 2005 by Ludger Lütkehaus on Zeit Online

- ↑ Essay by Kevin Jackson in the DVD edition of the Criterion Collection , 2008.

- ↑ Entry in the Internet Movie Database .

- ^ Entry in the archive of the Cannes International Film Festival 2012 , accessed on June 22, 2012.

- ↑ Interviews. Donald Keene On ... Yukio Mishima & Madame de Sade WhatsOnStage, March 19, 2009, accessed September 14, 2019

- ^ First editions of Mishima's works (Japanese)

- ↑ Daniel Strack: 三島 の 橋 づ く し Mishima no hashizukushi . Ed .: 日本 近代 文学 会 . S. 85-90 (Japanese, online (PDF) [accessed March 9, 2012]).

- ↑ Illustration in the Arno Breker Museum

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Mishima, Yukio |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | 三島 由 紀 夫 (Japanese); 平 岡 公 威 (Japanese, real name); Hiraoka Kimitake (real name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Japanese writer and political activist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 14, 1925 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Tokyo , Japan |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 25, 1970 |

| Place of death | Tokyo , Japan |