I have a dream

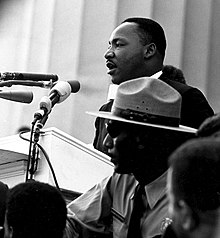

I Have a Dream is the title of a famous speech by Martin Luther King , which he gave on August 28, 1963 during the March on Washington for Work and Freedom in front of more than 250,000 people in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC stopped.

The speech summarized the most important current demands of the civil rights movement for the social, economic, political and legal equality of African Americans in the form of a future vision for the United States . It expressed King's hope for future consistency between the US Constitution , especially its principle of equality , and social reality, which was largely characterized by segregation and racism . The chorus-like repeated, spontaneously improvised sentence I have a dream in the final passages became the title of the speech. This became one of King's most cited speeches, exemplifying his conception of the American Dream .

Emergence

In May 1963, the civil rights movement under King's leadership in Birmingham had achieved the repeal of the city's racial segregation ordinance. On June 11, 1963, US President John F. Kennedy announced a new civil rights law in a televised address that would abolish racial segregation across the United States. As a result, white racists murdered Medgar Evers , the head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In order to help the planned Civil Rights Act in the southern United States to breakthrough, six leading civil rights organizations decided to organize the march on Washington . This became the largest mass demonstration in the United States to date and the historical climax of the civil rights movement. Around 250,000 people from all over the United States attended, around a third of them white. The demonstration demanded full equality for African Americans in all areas of society, and was peaceful and in great unity. King, as chairman of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), was slated to be the last in a long line of speakers. Late in the afternoon on a hot summer day, co-organizer Asa Philip Randolph introduced him to the crowd as the "moral leader of the nation".

The night before, King had asked his friend and adviser Wyatt Walker what the message of the speech was going to be. Walker advised him not to use the phrase "I have a dream" because it was clichéd and worn out. That night King finished his draft speech and handwritten the entire text. At around 4 a.m. he handed the finished text over to his employees to print out and distribute. An assistant found the handwriting in King's hotel room with many lines crossed out, including the phrase “I have a dream”. The passage thus introduced was not part of the first printed version. In the course of the day King revised the print version again, deleted and replaced many lines and words by hand. Because many listeners were exhausted after a long wait in the summer heat, he began to speak slowly and kept close to his manuscript. The bystanders noticed that he did not initially achieve the emotional connection with the audience that is typical for his speeches. Before the final passages he paused and took a breath. The previously performed gospel singer Mahalia Jackson called out to him twice: "Tell them about the dream, Martin!" Then King put the speech manuscript down and spoke the final passages freely, starting with "I have a dream".

rhetoric

King used his speech as a negative homage to the broken or for some - such as the African-American population of the USA - unattainable American Dream, in order to draw attention to the grievances of the situation of the African-American population.

The speech is counted among the masterpieces of rhetoric . King uses numerous quotes as allusions , for example from the Bible , the Declaration of Independence of the United States , the American Constitution , the national anthem , from the Emancipation Proclamation and the Gettysburg Address , both from President Abraham Lincoln and from William Shakespeare's drama Richard III. Knowledge of these texts is assumed by the audience.

Through the use of anaphers and the solemn presentation, the speech also has the effect of a typical Baptist sermon . In the African American churches in particular, sermons are structured in a dialogical manner, which means that the congregation responds through formalized heckling (“my Lord”, “oh yeah” etc.). This also succeeded here, because the majority of the black audience was socialized accordingly through church visits . As in a sermon, King used certain recurring formulas whose rhythm stimulates the audience and at the same time transports the content. At the beginning of the speech, for example, he alluded to Lincoln's emancipation proclamation from 1863 and then stated: “But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free” (“But one hundred years later the Negro is still not free”). The formula “one hundred years later” follows three more times in an anaphor. Other formulas that King used in the same way in the speech include "now is the time", "I have a dream", "let freedom ring" and "free at last".

Other rhetorical stylistic devices that King uses in his speech are the antithesis , the metaphor , the periphrase and the anadiplosis .

reception

politics

In the days following the March on Washington, King's speech generated positive press reactions and was widely considered the highlight of the event. The FBI, however, viewed King and his allies in the civil rights movement as subversive and decided to expand the COINTELPRO program against the SCLC and treat King as the main enemy of the United States. William C. Sullivan, then head of COINTELPRO, wrote in a memorandum two days after King's speech :

“In the light of King's influential demagogic speech yesterday, I personally believe that he ranks far above all the other Negro leaders combined in influencing large masses of Negroes. We must now, if we have not done so before, label him as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this nation, from the standpoint of communism, the Negro and national security. "

Historiography

Because of its cultural and historical significance for the United States, the speech was entered into the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress on January 27, 2003 .

According to historian Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, the narrative of the civil rights movement of the 1960s, with the I-Have-a-Dream speech as the culmination, dominates the image of King today. All other aspects of his work, such as his protest against racism in the north of the USA, his engagement against the Vietnam War or his large-scale Poor People's Campaign , in which he campaigned for trade union rights, fell into oblivion.

copyright

The speech was broadcast on the radio and the recording is the most widespread form of transmission. A transcription did not appear in the Washington Post until 1983 . In the opinion of Alexandra Alvarez, however, it represents a falsification, as important phonetic and poetic aspects of the speech as well as the reactions of the audience are lost in written form .

One month after the speech, King registered a copyright on the recording. The Intellectual Property Management department of the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change founded by King's widow in 1968 investigated cases of unauthorized re-use. In 1987 King's descendants sued producer Henry Hampton , who used the speech in the documentary Eyes on the Prize . In addition, were, among others, USA Today for a reprint of the 30th anniversary of the March on Washington for work and freedom sued and the BBC for the distribution of a video live recording specially recorded speech.

The action sparked a dispute over copyright in public speeches and was further fueled by the fact that journalists were banned from using them, but licenses for commercials were granted. In addition, the speech itself consisted of several quotations and metaphors taken from third parties. The defendant journalists were initially found to be right in court; however, after the plaintiffs appealed, the ruling judge ruled in 1999 that King's speech should be considered a worthy performance in front of a select audience and not a common good. The speech will be protected by copyright until 70 years after King's death, i.e. until the year 2038.

In 2009, the King Center transferred rights management to EMI Publishing for an undisclosed amount . In the film Selma , the speech had to be paraphrased to avoid litigation.

Additional information

literature

- Alexandra Alvarez: Martin Luther King's 'I Have a Dream': The Speech Event as Metaphor . In: Journal of Black Studies 18, Issue 3 (1988), pp. 337-357.

- Karl-Heinz Göttert : Martin Luther King's I-have-a-dream speech . In: Ders .: Myth of Speech Power. Another story of rhetoric . Frankfurt am Main 2015. pp. 124–130.

Web links

- The speech as text, sound and video (abridged version)

- Martin Luther King, Jr. “I have a dream” Full speech (1963 Washington) on Learn Out Loud (video, approx. 17 min., English)

- Martin Luther King, Jr. “I have a dream” Full speech (1963 Washington) on YouTube (video, approx. 17 min.)

- "I have a dream - address during the March on Washington for jobs and freedom" , US Diplomatic Mission to Germany, German translation.

Individual evidence

- ^ David Howard-Pitney: Martin Luther King Jr, Malcolm X, and the Civil Rights Struggle of the 1950s and 1960s. A Brief History with Documents. Bedford / St. Martins, Boston 2004, ISBN 0-312-39505-1 , pp. 102-104

- ↑ Britta Waldschmidt-Nelson: GegenPlayer: Martin Luther King - Malcolm X. 3rd edition, Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-596-14662-3 , pp. 95-97

- ↑ Anthony J. Does: Blurry Daydream: When Faith Feels Like Make Believe. WestBow Press, Bloomington 2017, ISBN 978-1-5127-9092-4 , pp. 22f.

- ^ Franz Kasperski: "I Have a Dream" - the speech that was planned completely differently. Swiss radio and television , April 4, 2017

- ↑ Alexandra Alvarez: Martin Luther King's 'I Have a Dream': The Speech Event as Metaphor . In: Journal of Black Studies 18, Heft 3 (1988), pp. 337-357, here pp. 342 ff.

- ↑ Alexandra Alvarez: Martin Luther King's 'I Have a Dream': The Speech Event as Metaphor . In: Journal of Black Studies 18, Issue 3 (1988), pp. 337-357, here pp. 340 f.

- ↑ Alexandra Alvarez: Martin Luther King's 'I Have a Dream': The Speech Event as Metaphor . In: Journal of Black Studies 18, Issue 3 (1988), pp. 337-357, here pp. 342-348.

- ^ The FBI's War on King

- ^ I Have A Dream in the National Recording Registry. Retrieved August 17, 2017 .

- ↑ Jacquelyn Dowd Hall: The long civil rights movement and the political instrumentalization of history. In: Michael Butter , Astrid Franke, Horst Tonn (eds.): From Selma to Ferguson - Race and Racism in the USA. transcript, Bielefeld 2016, ISBN 978-3-8394-3503-8 , p. 16 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Alexandra Alvarez: Martin Luther King's 'I Have a Dream': The Speech Event as Metaphor . In: Journal of Black Studies 18, No. 3 (1988), pp. 337-357, here p. 338; a transcription in verse that takes into account vocal increases and the audience's responses, ibid., pp. 350–356.

- ^ Controversy over Martin Luther King speech: Thoughts are not free. Spiegel Online, August 26, 2013

- ↑ John Fund: 'We Have a Brand!' National Review, Jan. 4, 2015