Imperial British East Africa Company

The Imperial British East Africa Company ( IBEA ) was a commercial British company , the 1888-1895 British East Africa managed to become the predecessor and also pioneered the later British colonial authorities in Kenya and Uganda showed.

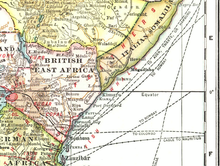

The IBEA was founded after the Berlin Congo Conference to stimulate and control trade in the areas of East Africa allocated to Great Britain . The starting point of the operations was the port city of Mombasa on the East African coast. The IBEA's approach was marked by mismanagement and led in 1895 to the takeover of the administration of the areas of British East Africa and Uganda by the Foreign Ministry of Great Britain.

Foundation and goals

In the course of the division and conquest of the African continent, at the Berlin Congo Conference in 1884/85 the great powers agreed to place the areas of today's Kenya and Uganda under British influence. Since Great Britain was heavily burdened by its activities in the Cape Colony , the British Crown first placed the territory of today's Kenya and from 1890 the territory of Uganda under the administration of the IBEA.

The IBEA was dominated by business people who were already closely involved in trade between East Africa, India and Europe. The chairman was the Scottish shipowner and businessman Sir William MacKinnon , a prominent administrative member of the former Consul General in Zanzibar , John Kirk , many other members were among MacKinnon's business friends. The company received no financial support from the British government. With a modest capital of £ 250,000, the IBEA wanted to stimulate trade in Uganda and along the East African coast, bring it under its own control and create sales markets.

A primary goal was to gain control of the East African ivory trade and eliminate competition from Indian and Swahili merchants. Ivory was East Africa's most important export item in the 19th century . The demand for ivory for piano keys, billiard balls and other luxury goods had increased immensely in the western markets due to the strengthening of the middle class in the 19th century. Caravans with several thousand people traveled from the coastal cities to the inter- sea region , to Buganda and as far as the Congo to buy ivory and bring it to the coast. In order to intervene in these established trading systems, the IBEA had to secure the 600 mile long trade route from Mombasa to Uganda for their caravans. Up until that point in time, Uganda had only been reached from the coast via routes further south. But since this is now the German Reich awarded area German East Africa were, one was interested in their own trade.

Mombasa as the seat of the IBEA

The IBEA acquired from the Zanzibari sultan a concession over a ten-mile-wide stretch of coast and all rights to administer it. The company set up its headquarters, also casually called Coy by the employees , in the port city of Mombasa, which was considered the capital of British East Africa. At that time Mombasa was the largest place in the British part of the East African coast and a hub for trade that was carried out with the region of Mount Kenya. Trading houses from India, Arabia and Europe had branches here. Zanzibar , seat of the Sultan of Oman and an international hub for trade and political developments, was easy to get to.

The IBEA organized the garbage disposal in the city center, built a hospital with twelve beds for white people and its own port buildings. She had rails intended for a railway line in the interior laid out on the island, on which the Europeans could be pushed through the city by African servants in draisines with a linen roof. New shops and an office were built in the main street Ndia Kuu , the administration's residence was Leven House on the harbor promenade, where the British consulate in the Sultanate of Zanzibar had previously resided.

The mostly young employees set up in Arab stone houses. They soon had a bad reputation among both the native Swahili population and non-Company whites. The shop of the Goan merchant MR de Souza became a meeting place for all whites - apart from the missionaries of the two nearby mission stations, who found the pleasurable behavior of the company employees improper and immoral. In fact, many observers reported countless parties and receptions, as well as sailing and shooting competitions and other social events that often ended in drinking parties.

At the end of 1891, the IBEA comprised eight administrative sectors: finance, taxation, shipping, transportation, public affairs, postal services, medical care and a head office. At that time, however, the staff did not include more than 25 Europeans, some of whom lived with families in Mombasa. The fluctuation among European employees was high, and a large number died of tropical diseases. The IBEA military force consisted of two companies of Sudanese soldiers who had been recruited in Cairo; In addition, there was a 200-man police unit made up of trained police officers recruited in India.

Stations

From 1889 onwards, the IBEA established a number of administrative posts along the central caravan route from Mombasa to Lake Victoria on its exploratory expeditions. The stations were usually in places that had already established themselves as trading centers in the interregional caravan trade in the previous decades. The most important of them were Machakos and Dagoretti , later Kikuyu (or, since it was newly founded by Major Smith, also called Fort Smith), followed in 1894 by Eldama Ravine and Mumias . The stations were small and thinly staffed, usually by one or two young Europeans and fifty to one hundred African helpers who were deployed as porters, soldiers or messengers as required.

The task of the stations was to provide resting places for the IBEA caravans passing through and to provide them with food for their onward journey. For this purpose, food was bought in large quantities from the neighboring population, as the caravans often comprised up to a thousand or more people. But it also happened again and again that raids and so-called “ punitive expeditions ” were carried out against the local population. Nevertheless, the stations developed into lively hubs for trade and communication, where small traders, adventurers or outcasts from the surrounding communities settled. Since the company was always dependent on porters and other workers, they were points of attraction for people who were looking for opportunities to earn a living, who wanted to participate in the large ivory business and who wanted to bargain for coveted European goods such as weapons, clothing, pearls or tobacco and thus became the nucleus for themselves later developing cities.

Even if the stations in their area certainly exerted a certain influence, one cannot speak of control or even domination of the IBEA domestically. The few Europeans were dependent on good relationships with the local population, not only to ensure that the caravans were supplied. In order to survive alone, they formed alliances with local authorities who, in turn, hoped for advantages from the Whites. It was only possible to hold a station with diplomacy and restraint. The methods used out of fear and inexperience to threaten, even punish, capture and kill locals turned out to be unwise. In the case of Dagoretti station, it even meant that the station was burned down by angry Kikuyu and later had to be rebuilt.

Expeditions

Since the IBEA was primarily interested in trade and therefore in transport routes, the IBEA's first major venture was an expedition led by Frederick John Jackson , who had been an ornithologist and ivory hunter in East Africa since 1884. He was supposed to find a safe route for the IBEA caravans through the area to Lake Victoria , which so far had only been traveled by very few Europeans. Jackson traveled in 1892 on a pre-existing route used by local traders that passed through the waterless region through Kibwezi, Machakos and Kikuyu, to Uganda and then returned. Further expeditions of the IBEA led by Frederick Lugard to the river Sabaki and under John Pigott along the river Tana , during which it was found that the hoped-for use of the waters as traffic routes was not possible.

Transport and communication

In 1890 work began on a road for ox carts, which was supposed to enable transport by vehicles and thus save on the numerous carriers previously required. The road was intended to connect Mombasa and Uganda and was later commonly referred to as the Mackinnon-Sclater Road . It led via Kibwezi and along the caravan route to Busia north of Lake Victoria. Since MacKinnon financed the construction of the first section, the line between Mombasa and Kibwezi was named after him. Captain BL Sclater, head of a surveying team for the Uganda Railway, continued construction of the road into the Rift Valley in 1894, while the last part until Busia was taken over by his colleague Captain GE Smith.

In 1890, work began on a narrow-gauge railway line that was supposed to cross the dry area behind the coastal belt into the interior. However, after the completion of eight miles, the work stopped as the company could not raise further funds. A small steamer was imported from England in individual parts, transported to Lake Victoria and, assembled there, was supposed to provide the connection between the eastern and western seaside.

In 1891 the ports of Mombasa, Malindi, and Lamu were linked by telegraphs set up by the Eastern Telegraph Company.

Takeover by the British Foreign Office

Since the administration of the company was poorly financed from the beginning and its employees were characterized in many places by incompetence and corruption, the IBEA was soon heading for bankruptcy. In 1893 it gave up Uganda and from 1895 Kenya was also administered by the British Foreign Office. Until the Uganda Railway was completed in 1902, little changed in the administration of the area. Most of the company's employees were taken over into the service of the Crown and continued with their previous practice of diplomacy and temporary demonstrations of violence.

Despite the short period of its existence, the work of the IBEA had lasting consequences. Their staff decisively determined the subsequent colonial politics, many of their employees were highly regarded as pioneers of colonial administration and made careers within the colonial hierarchy. For example John Ainsworth (1864-1946), who administered Machakos station from 1891 to 1898, then had great influence on the establishment of the reservations and later rose to become Chief Native Commissioner of the Colony of Kenya, or Frederick Jackson, the first governor of Kenya and between 1911 and 1918 was governor of Uganda.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Charles W. Hobley: Kenya. From Chartered Company to Crown Colony. Thirty Years of Exploration and Administration in British East Africa. Witherby, London 1929, pp. 24, 29 (2nd edition, with a new Introduction by GH Mungeam. (= Cass Library of African Studies. General Studies. Vol. 84). F. Cass & Co, London 1970, ISBN 0- 7146-1679-6 ).

- ↑ a b c d Christine S. Nicholls: Red Strangers. The White Tribe of Kenya. Timewell Press, London 2005, ISBN 1-85725-206-3 , pp. 3, 8-11, 15-17.

- ^ Paul Sullivan (Ed.): Kikuyu District. Francis Hall's Letters from East Africa to his Father, Lt. Colonel Edward Hall, 1892-1901. Mkuki Na Nyota, Dar es Salaam 2006, ISBN 9987-41757-4 .

- ^ Charles H. Ambler: Kenyan Communities in the Age of Imperialism. The Central Region in the late 19th Century (= Yale Historical Publications. Vol. 136). Yale University Press, New Haven CT et al. 1988, ISBN 0-300-03957-3 , pp. 106-114.

- ^ William R. Ochieng ', Robert M. Maxon (Ed.): An Economic History of Kenya. East African Educational Publishers, Nairobi 1992, ISBN 9966-46-963-X , p. 131.

- ^ Charles H. Ambler: Kenyan Communities in the Age of Imperialism. The Central Region in the late 19th Century (= Yale Historical Publications. Vol. 136). Yale University Press, New Haven CT et al. 1988, ISBN 0-300-03957-3 , p. 107.

- ^ Robert M. Maxon: John Ainsworth and the Making of Kenya. University Press of America, Lanham MD 1980, ISBN 0-8191-1156-2 .