Bible film

The processing of material from the Bible in film has been a recurring motif in film narration since the silent film era . The Bible film stands in the conflict between commercial entertainment and theological-Christian faithfulness to the work. He often uses motifs from Genesis (creation story, Noah's Ark , Sodom and Gomorrah ) and other well-known stories and people from the Old Testament (such as Moses , to whom the Ten Commandments are given, the couple Samson and Delilah , Ruths or King David ). From the New Testament , the Gospels in particular are thematized, or individual persons from them (e.g. Jesus , the Virgin Mary or Salome ).

history

The beginnings: the silent film

The first silent films with reference to the Bible were devoted to the Passion of Jesus in 1897 . The material was first filmed by the brothers Albert and Basile Kirchner and Georges-Michel Coissac, and shortly afterwards by the Lumière brothers . The early Bible films with a length of 10 to 15 minutes loosely lined up individual scenes in which amateur actors acted.

The church initially reacted with reserve. In a pastoral letter it says about the new medium of film: “The worst thing is that this great invention is also often misused for wickedness, that the slide stage is often turned into a new stage for fornication.” However, after the turn of the century the church recognized the potential of the new medium and tried to assert copyright claims.

From 1910 onwards, the Jesus films became more complex: The films were now shot in historical locations such as Egypt, and the films were given subtitles, often individual quotations from the Bible. The length of the films increased, and the roles were no longer predominantly cast with unknown amateur actors, but rather with professional actors.

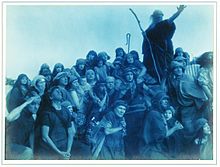

The bloom: monumental films

From 1920 onwards, the films increasingly concentrated on the entire story of the Old Testament or individual characters from it. Neglecting the narrative elements, material battles with crowd scenes and elaborate backdrops were preferred. With more than 50,000 extras in some cases, the curiosity of cinema-goers was satisfied. During this time, the films Samson and Delila by Alexander Korda , Sodom and Gomorrha by Michael Curtiz (both 1922) and The Ten Commandments (1923) by Cecil B. DeMille were made .

With the invention of the sound film in the 1930s, it was possible to intensify the fidelity of reality through sounds and background music. Now the crucifixion scenes in particular were shown more vividly, so that the suffering of Jesus, the nailing to the cross, his pains could be experienced by the audience.

After the war, it was Cecil B. DeMille who convinced Paramount to take up a Bible adaptation that had been in the drawer for over a decade. With Samson and Delilah (1949) the resurgence of Bible film began in Hollywood. The unexpected success also made the other large film studios plan in this direction. First, 20th Century Fox started with David and Bathsheba (1951). Later came the Columbia with Salome added (1953). In addition to the elaborate technicolor scenery, it was above all the melodramatic love stories that secured the favor of the audience. The first film of this genre in CinemaScope was Temple of Temptation (1955) and was released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer . The wave of success continued with The Ten Commandments (1956), in which the productions tried to outdo each other with ever larger crowd scenes and thousands of extras, and which culminated with Ben Hur (1959).

In the 1960s, there was some refrain from tracing all the details of the Bible effectively. The miracles of Jesus in King of Kings by Nicholas Ray are only indirectly hinted at and Jesus is humanized. The films tried to carefully characterize Jesus, e.g. B. in The Greatest Story Ever (1963). In the 1960s, producer Dino De Laurentiis also attempted to adapt the Bible as a chain of films, including The Bible (1966) by John Huston . Roberto Rossellini tried in his "didactic television films" to tell The Story of the Apostles (1969) in five parts .

Critical films, satires and musicals

In the late 1960s, but also in the years before, the historical forms of representation receded in favor of biographical or fictional elements. An "erosion of the direct but naively lived faith" was recognizable, so that Bible adaptations instead of heroism were now about doubt and human weakness.

This was accompanied by a changed aesthetic, which was expressed in the Nouvelle Vague . Pier Paolo Pasolini made one of the most radical Bible films of this time with The First Gospel - Matthew (1964), which sparked heated controversy after its publication. As the biblical material was dealt with more freely, parodies such as The Life of Brian (1979), The Ghost (1982) or Jesus - The Film (1986) were created in the years that followed . In addition, musical films such as Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar (both 1973) were great audiences.

In the 1980s, apart from The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) by Martin Scorsese , Jesus of Montreal (1989) should be mentioned. In his “allegorical transmission”, which has won numerous awards, Denys Arcand located the role of Jesus in the church of that time. In the early 1990s, Leo Kirch commissioned what is probably the most ambitious film adaptation of the Bible, in which he made the Bible in a total of 12 parts between 1993 and 2000.

present

Bible films in the classic sense had all but disappeared by the 2000s. Films like The Passion of the Christ (2004) were considered exceptional. The genre has only experienced a renaissance since the 2010s, when the Hollywood studios began to focus on the well-known materials during the crisis. Thus Noah and Exodus: Gods and Kings (both 2014) expression of a new wave of Bible movies.

See also

Web links

- Bible films (Old Testament) and Bible films (New Testament) in the WiBiLex

- Udo Wallraf: Bible in Film. Aspects of an Approach . In: Erzbistum-Koeln.de , 2001 (last changed on November 20, 2009; PDF, 51 kB).

- Bible films. A selection from the rental program of the media center of the Archdiocese of Cologne . In: Erzbistum-Koeln.de , 2006 (last changed on June 3, 2009; PDF, 264 kB).

literature

- Richard Campbell, Michael Pitts: The Bible on Film . A Checklist 1897-1980. The Scarecrew Press, Metuchen 1981.

- Bruce Babington, Peter William Evans: Biblical Epics: Sacred Narrative in the Hollywood Cinema . Manchester University Press, Manchester 1993.

- Peter Hasenberg (Ed.): Traces of the Religious in Film. Milestones from 100 years of cinema history . Catholic Institute for Media Information (KIM) / Matthias-Grünewald-Verlag, Cologne / Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-7867-1827-X .

- Erin Runions: How Hysterical. Identification and Resistance in the Bible and Film . Palgrave Macmillan, London 2003.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Manfred Tiemann: Bibelfilme (AT). In: The scientific Bible dictionary on the Internet . June 2012, accessed March 11, 2014 .

- ↑ a b c James zu Hüningen: Bibelfilm. In: Lexicon of film terms. Hans J. Wulff and Theo Bender, accessed March 11, 2014 .

- ↑ http://www.hervedumont.ch/L_ANTIQUITE_AU_CINEMA/files/assets/basic-html/page423.html

- ^ A b c d Manfred Tiemann: Bibelfilme (NT). In: The scientific Bible dictionary on the Internet . June 2012, accessed March 11, 2014 .

- ↑ a b Big Stars in Big Stories. ORF , December 25, 2013, accessed on March 11, 2014 .

- ↑ a b c d e Udo Wallraf: Bible in the film. Aspects of an Approach . In: Erzbistum-Koeln.de , 2001 (last changed on November 20, 2009; PDF, 51 kB).

- ↑ a b James zu Hüningen: Jesus film. In: Lexicon of film terms. Hans J. Wulff and Theo Bender, accessed January 12, 2014 .

- ↑ Hollywood's new old heroes come from the Bible. Westdeutsche Zeitung , January 3, 2014, accessed on March 11, 2014 .