Brian's life

| Movie | |

|---|---|

| German title | Brian's life |

| Original title | Monty Python's Life of Brian |

| Country of production | United Kingdom |

| original language | English |

| Publishing year | 1979 |

| length | 94 minutes |

| Age rating | FSK 12 |

| Rod | |

| Director | Terry Jones |

| script | Monty Python |

| production | John Goldstone |

| music |

Geoffrey Burgon , Eric Idle |

| camera | Peter Biziou |

| cut | Julian Doyle |

| occupation | |

| |

The life of Brian (Original title: Monty Python's Life of Brian ) is a comedy by the British comedian group Monty Python from 1979 . The naive and inconspicuous Brian, born at the same time as Jesus , is revered as the Messiah through misunderstandings against his will . Because he is committed against the Roman occupiers , he ends up in a mass crucifixion .

The satire aims at the dogmatism of religious and political groups. Especially Christian , but also Jewish organizations reacted with sharp protest to the publication. The following performance boycotts and bans in countries such as the United States , the United Kingdom, or Norway further fueled the controversy over freedom of expression and blasphemy .

Although the accusation of blasphemy has been refuted from practically all sides, satire is still controversial among Christians and, due to its importance in the history of reception, is considered a prime example of the points of friction between artistic freedom of expression and tolerance of religion. Film critics and the pythons themselves refer to Brian's Life as the comedian's group's most mature work because of its coherent story and intellectual substance. Numerous surveys confirm the continued success with the public. The closing song Always Look on the Bright Side of Life became known far beyond the film context.

The British Film Institute voted Brian's Life the 28th best British film of all time .

action

Brian, the result of an affair between the Jewess Mandy Cohen and a Roman soldier, Nixus Minimax, is born in the stable next to that of Mary and Joseph . Dominated by his imperious mother, he grows up to be an inconspicuous man in Judea . He falls in love with the idealistic Judith, who is involved in the “Popular Front of Judea”, a Jewish resistance group against the Roman occupiers. Brian successfully tries to get accepted into this group and participates in their break-in into the palace of Pontius Pilate : There, the freedom fighters want to kidnap the governor's wife and so bring down the Roman Empire. The kidnapping fails because another of the numerous splinter groups, the “Campaign for a Free Galilee”, are pursuing the same goal with the same plan at the same time. Brian is arrested in the palace and dragged for a hearing before Pilate. Thanks to a fit of laughter from the palace guards and an alien spaceship that happens to pass by, Brian escapes the impending condemnation by escaping the palace.

In order not to attract the attention of the Roman search party on the busy market square, he has to slip into the role of one of the numerous prophets . His clumsy stuttering puzzles the few listeners, which make interest in him grow, and so he soon has a large following behind him who are hoping for answers to all questions in life from him. The steadily growing crowd of followers pursues the fleeing Brian into the barren countryside, argues over the symbolic power of a sandal lost by Brian and considers banalities such as the existence of a juniper bush to be miracles performed by Brian. Finally, a hermit annoyed by the crowd , with whom the overwhelmed Brian wanted to hide, is led away as a heretic by the mob to be executed. Meanwhile, Judith is impressed by Brian's charismatic charisma. He spends his first night of love with her.

The next morning the streets of the city are overcrowded with disciples of Brian waiting under his window for messages of salvation. Brian unsuccessfully points out the nonsense of following a leader uncritically. In the backyard he is arrested by the legionnaires and brought back to Pilate, who sentenced him to death by crucifixion along with over a hundred other delinquents who had apparently been chosen at random . Rescue attempts fail or are not even considered: Both his lover and the resistance fighters congratulate Brian on his selfless martyrdom on the cross . His mother accuses him of selfishness. Only a happy crucified man asks the desperate Brian to look at the sunny side of life despite grueling senselessness. In his song Always Look on the Bright Side of Life , all those sentenced to death join in elated.

Production history

Script development

The members of the comedian group Monty Python met on a promotional tour for their film The Knights of the Coconut in Amsterdam in early 1976 . In a bar, Eric Idle and Terry Gilliam joked about Jesus, who was nailed to the cross as a trained carpenter. At the premiere of that film in New York , Idle had an idea for a new project: Jesus Christ - Greed for Fame. The provocative topic seemed promising enough to the pythons, who were already pursuing their solo careers at the time, to get back together. The surprising commercial success of The Knights of the Coconut also had a motivating effect on the group.

Since working together on Monty Python's Flying Circus , permanent teams of authors had established themselves: Michael Palin mostly designed his skits with Terry Jones , John Cleese worked with Graham Chapman , while Eric Idle and Terry Gilliam were the two loners of the group. At the first writers' meeting in late 1976, the pythons read randomly written scenes on the subject, and the group decided what they liked and what they didn't. The Pythons soon developed the idea of a forgotten, clumsy 13th Apostle named Brian, who is late for all divine events. But the pythons couldn't and didn't want to joke about Jesus himself out of respect, which turned out to be a hindrance when working on the comedy.

Through their intensive research they came across in history books "that messiah fever was rampant in Judea at that time", as Michael Palin reported. On this basis they created a character who had a life story that ran parallel to Jesus, but was clearly not Jesus. Brian of Nazareth , mistaken for a Messiah, established himself as the dominant theme. During the other writers' meetings in a creative atmosphere, Gilliam and Jones insisted most of all on making a coherent story out of the individual sketches. When Michael Palin finally read out his sketch about a Pontius Pilate with a speech impediment, the decisive element for the film was found.

Jesus himself also reappeared in the script: the jokes did not ignite himself, but were directed against the audience of the Sermon on the Mount . In order to find a comical approach to the crucifixion, the authors Terry Jones and Michael Palin had to focus on the everyday nature of this method of execution at the time. “Sometimes 500 to 600 people were crucified in a day. […] We toyed with the idea that there are accidents and that things go wrong […] “The search for a satisfactory ending turned out to be particularly difficult. Eric Idle's idea to end the film with a light-footed, musical chant on the cross was finally accepted by the skeptical Terry Jones. Based on the previous material, the scene was created in which Brian at the window calls out to his followers to think for themselves. Jones: "In it, so to speak, the threads of the story came together."

As the title of the new film, in addition to the alternatives Brian of Nazareth and Monty Python's Brian, the suggestion Monty Python's Life of Brian prevailed.

In January 1978, the six writers spent two weeks in a Barbados beach house finishing the script . The cast has also been fixed. Years later, Michael Palin recalled: " Brian's life was the last good group experience when it came to writing." Because everyone knew they were moving on sensitive terrain, Graham Chapman brought the finished script to a known canon of the Queen . The pythons noted with satisfaction that he had read it with pleasure and without objection.

Pre-production

Funding difficulties

The Monty Python members worked on the script without arranging funding. In fact, EMI employee Barry Spikings became interested in the project when he happened upon Eric Idle in Barbados. A little later he secured John Goldstone, who was chosen by the Pythons as their producer, the necessary funds. But two days before the planned departure for the filming in Tunisia , EMI board member Bernard Delfont rejected the project: he had read the script and found it offensive. At this point the production contract had not yet been signed; Funds equal to the budget of Monty Python's wonderful world of gravity had already been invested. On the one hand, Monty Python had to enforce his claims on the previous expenses in court, which the group was finally granted. The search for a new producer turned out to be difficult - probably because the material seemed too explosive to potential producers.

Eric Idle told his friend, ex-Beatle George Harrison , about the difficulties in finding the roughly four million dollars he needed. Harrison then made the money available from his own resources: he founded HandMade Films with his managing director Denis O'Brian to produce the film, "apparently only because he wanted to see the film."

Cast and direction

The Pythons agreed on the cast during the final writing phase. Often the writers played their own material unless there was something against it. “We were 80 percent writers and 20 percent actors, and as writers it was very important to us that the casting was right. […] We were less interested in our egos as actors, ”said John Cleese of the mostly uncomplicated casting process. At Life of Brian there were still major cast discussions. A difficult question was the adequate cast of the figure of Jesus. Finally, an agreement was reached on Ken Colley and, for example, George Lazenby suggested by John Cleese was rejected . Cleese sparked further discussion when he tried to take on the lead role. He justified this with his desire to "hold out a character from the beginning to the end of a film". Michael Palin suspected that Cleese had "sacrificed" himself and wanted to prevent Graham Chapman from taking over the title role. For years the collaboration with Chapman suffered from his alcoholism. But especially Terry Jones favored Chapman: In the previous production, he had noticed his credible charisma in the role of Arthur . “That was hugely important to me in comedy - more important than the lead character being funny.” For his part, Graham Chapman decided to face his addiction problem and went through rehab. It was not just his now concentrated way of working as an actor that had a positive effect on the shooting: the medical graduate took care of the health of his colleagues on the set after the shooting ended. Eric Idle summarized: "Graham became a downright saint."

In the previous production, The Knights of the Coconut , the group decided to have Terry Jones and Terry Gilliam co-direct. However, irreconcilable artistic differences between the two had put a lasting strain on the working atmosphere. Therefore, this time the Pythons agreed on Jones as sole director. The visually savvy Gilliam, who had always been responsible for the animations , took on the production design . Gilliam, who worked with “real actors” at Jabberwocky and started his career as a feature film director, was very satisfied with this solution. Terry Jones later also spoke of an ideal combination under which he would work again at any time.

Production design

From the beginning, the Pythons had ambitious goals with The Life of Brian . Michael Palin: “[We] wanted to not just have a few jokes in front of painted scenes at Shepperton Studios on Brian's life, we wanted to use extras that really looked like Jews or Arabs and some real heat to make it more authentic . There were so many bible hams that looked like they had been shot in the north of England. ”Jones and Gilliam chose Tunisia as the location. There they were able to benefit from Franco Zeffirelli's multi-part series Jesus of Nazareth (1978), which was also created in Monastir , Tunisia : A large part of Zeffirelli's sets, costumes and props were available for the shooting. Further Roman costumes and props for Life of Brian came from the fund of the Tirelli costume rental and the Cinecittà in Rome . Charles Knode and Hazel Pethig, who had already worked in this role at Monty Python's Flying Circus , acted as costume designers . Maggie Weston, Terry Gilliam's wife, was part of the production team as a makeup artist .

The new buildings under the direction of Gilliam were essentially a hypocaust , through which the resistance fighters were supposed to break into Pilate's palace, some statues that were formed from Styrofoam like the stones for the stoning sketch , and some additions, for example near the ruins an amphitheater that was used as a Coliseum . Gilliam seemed particularly proud of the design of Pilate's audience hall: "[...] they showed how the Roman order tried to defeat the Jewish chaos." To Gilliam's bitterness, one could hardly see the elaborate and expensive setting in the finished film, what led to renewed resentment between him and Terry Jones.

Filming

After the rehearsals, the five-week filming began in Tunisia on September 16, 1978. When working on a Monty Python film, the group usually made decisions after discussions. Pythons that were not in front of the camera gave helpful criticism as viewers. The fact that the actors were the authors of their texts helped with the filming. Eric Idle: "You don't have to learn anything because you've read it all the time."

The first scene filmed was the stoning, which was filmed on the fortress walls of the Ribat in Monastir and thus at the same place where Zeffirelli had staged the stoning scene for Jesus of Nazareth . John Cleese later fondly remembered the working atmosphere that was efficient at the beginning: “Visitors to the set could have believed we were in the fifth week of shooting.” Terry Jones' intensive preparation won the critical Pythons respect, even if Jones, like everyone else played several roles, sometimes in women's clothes or stark naked had to give stage directions. Michael Palin looking back: "You don't take [stage directions] very seriously."

In terms of camera technology, the work was very uncomplicated. According to Terry Jones, 50 to 60 percent of the film was filmed with a 35 mm handheld camera in order to save the time and effort involved in assembling and disassembling the tripod. The only shot that was difficult to achieve turned out to be the scene with Michael Palin as an ex- leper who wanted to get a handout from Brian , even though Jesus miraculously cured his illness. He follows Brian from the city wall to his apartment - a path through the bustle of the market square, which the cameraman John Stanier had to film in reverse in the scorching heat with a heavy camera in hand.

After intensive work on the script, hardly any dialogue changes or improvisations took place during the shoot . One of the exceptions was the scene in which the revolutionaries were supposed to hide from the legionnaires during the house search. Eric Idle and Terry Gilliam as speech-impaired prison guards who harass Michael Palin as a patient, lovable centurion , also made room for extensive improvisation in their scene.

The pythons came as a big surprise when Spike Milligan appeared . The veteran comedian ( The Goon Show ) accidentally stayed at the same hotel to visit the battlefields where he fought in World War II for the first time after the war . The Pythons offered their role model, with whom they had to do closer for the first time, a small role in the film. In the scene in which Brian's supporters argue about the meaning of the lost sandal, Milligan gave the prudent old man who the obsessed group carelessly passes by. To the astonishment of the pythons, Milligan himself left the filming location during the lunch break to continue his vacation, although further recordings were planned. George Harrison also took on a small role when he visited the team and looked at previously filmed material: John Cleese introduces him in the film as the man who “gives Brian his mountain for a sermon on Saturday”.

Crowd scenes

Terry Jones faced the lavish crowd scenes very early on. The shooting of Pontius Pilate's speech to the citizens of Jerusalem took place in the first week of shooting: Around 450 Tunisian extras were supposed to throw themselves to the ground laughing because of Pilate's speech defect. Terry Jones hired a local comedian, but hardly anyone laughed. So Jones did what he wanted from the extras, threw himself on his back and started yelling loudly with laughter. As Jones reported, the crowd enthusiastically imitated him. But because no camera was running, this spontaneous moment for the film was lost. "That was one of the craziest situations of my life."

The scene under Brian's window, which was filmed a few days later, managed with fewer extras, but was more complicated: the crowd had to have a dialogue with Brian's mother in unison . A handful of English vacationers were recruited as extras and placed in the front rows behind the actors. The other 200 or so extras were Tunisians who spoke no English. Terry Jones called out the sentences for the crowd to speak in unison. He intended to dub the scene, but “the crowd was perfect. They didn't know what they were calling. They just called back what they heard from me. And finally we used that. "

At the beginning of this sequence, as Brian, Graham Chapman unsuspectingly opens his bedroom window and stands naked in front of his fanatical crowd. Eric Idle reported that the Arab women were "shocked and upset". Terry Jones later explained that Chapman had to be filmed separately because the extras included mostly Muslim women, who are forbidden to see a naked man.

In October, the last scene, the Sermon on the Mount, was filmed, which required a particularly large number of extras. The shooting took place in Matmata south of Gabès , the desert in which the desert sequences of the first Star Wars film were made. Terry Jones tried to create the illusion of a huge audience in the vast desert landscape with only around 200 extras. Kenneth Colley in the role of Jesus stood on a hill, the camera was set up on another hill. The extras were distributed on both surveys; the valley in between remained deserted, but could not be seen by the camera. This should give the impression that the crowd would also fill the valley.

The scene at the Colosseum, which was shot in Carthage during the last few days of shooting , made up for the lack of costly extras, according to Terry Gilliam, with creativity: “It should be an afternoon show that nobody watches. [...] We always had small budgets. Instead of going straight to things, you have to think about something. And ultimately that's always more interesting. "

crucifixion

As expected, the three-day filming of the crucifixion scene was exhausting. Shortly before shooting began, it had rained heavily, it was windy and cold. The sick John Cleese was able to get himself wrapped in a thick blanket as a crucified person. Gilliam had a cross with foot rests and bicycle seats constructed for each actor: “So we had everything determined, but Terry [Jones] changed his mind and put everyone on the wrong cross. So it was really painful. "

The team argued a lot about the question of how authentic the depiction of the crucifixion could be. "There were some people in the group who were afraid it would be too realistic and that it would detract from the humor," said Terry Gilliam, who would have had no problem nailing his hands with the blood spattering. According to Terry Jones, the hesitation led to two versions being shot. Because those with the nails were shocked at the test demonstrations, Jones used the settings in which the hands were only tied for the final cut.

The closing song Always Look on the Bright Side of Life was changed by composer and performer Eric Idle while filming, after he had played the first seriously performed version on location: “Everyone liked it and everyone applauded, but I thought: 'Something That's not true yet. [...] '“Idle was soon sure that the song would have to be interpreted happily and carefree. In the hotel room, which was insulated with mattresses, he recorded the singing again. This main voice, sung in Tunisia, can be heard in the film alongside the professionally recorded and arranged orchestra.

Animations and special effects

Terry Gilliam was responsible for the visual effects. For example, he had a painted stencil made about four meters high for Jerusalem, which was photographed from a distance. The ruins of an amphitheater in Carthage were used for the Jerusalem Coliseum. The lack of imposing effect was compensated for by a matte painting with architecturally impressive arches - a film trick technique that was also used in a shot that shows Pilate's palace walls smeared with anti-Roman graffiti. Because the ancient walls were not allowed to be smeared, Terry Gilliam built a wall backdrop in front of them for recordings in which matte painting could not be used.

Gilliam's main role at Monty Python since its inception has been the creation of humorous animations that are supposed to connect individual skits. In The Life of Brian there was no need for these surrealist short cartoons due to the stringent plot. Instead, Gilliam animated an elaborate opening credits for The Life of Brian , as usual with cut-out characters and under his own direction . “You have to see it several times to see everything. There's a story in there. This little character sits in heaven, in God's land, and is struck on earth and goes through some adventures. ”Despite all the pride in his animation, Gilliam saw his future in real film for a long time. With the decision to incorporate a science fiction sequence staged by Gilliam into the film, the pythons not only accommodated Gilliam's ambitions: the pythons' humor should always be characterized by unpredictability.

In the highly acclaimed sequence, the escaping Brian falls from a tower when a spaceship that accidentally rushes by catches him to save him. The aliens, with Brian on board, engage in a wild space battle with an enemy spaceship, before their spaceship rushes to Earth and hits Jerusalem, where Brian emerges unharmed from the wreck. When the rubble had to be built, the film budget was exhausted. Gilliam improvised with no longer needed parts of the scenery and found objects from the junkyard.

The shots with Brian in the spaceship were made in London, two months after filming in Tunisia ended. “The whole thing was shot in a room measuring six and a half by eight and a half meters. There we built the interior of the spaceship, shook it up and created these crazy creatures. ”It was not only because of the confined space that the work for Graham Chapman brought some stress. He was living in Los Angeles at the time and was not allowed to be in England for more than 24 hours for tax reasons. He spent about eight of them in the box before flying back exhausted.

Gilliam approached the subsequent work on the space battle in a playful way. Because he had no special effects experts to realize the spacecraft explosion when it hit an asteroid, "we went to a joke shop and bought all the exploding cigars they had, scraped out the powder and made a small bomb." For the sound effects he picked up a motorcycle while accelerating. “We learned how to do these things with these films,” said Terry Gilliam, who says he felt like a well-paid film student.

post processing

At the end of the shooting there was a film that was over two hours long. The planned opening scene with shepherds swarming with sheep and Pontius Pilate's wife, who gives the revolutionaries a wild chase, have been cut out.

One of the most controversial scenes was also removed: Eric Idle wrote and played Otto, leader of the suicide squad of the "Judean Popular Front", who is looking for Brian to be the "leader" who will "free Israel from the scraps of non-Jewish people" in order to found a thousand-year-old Jewish state. Finally, Eric Idle himself suggested cutting out the scene: in his opinion, the character was introduced too late and upset the balance of the film. Director Terry Jones and John Cleese agreed with him, only Terry Gilliam assumed idle fear of the Jewish producers in Hollywood: "I said: 'We have offended the Christians, now it's the turn of the Jews.'" Robert Hewison pointed out in his book Monty Python: The Case Against also points out that with the "Jewish Nazi Otto" problems with the Jewish lobby in the United States were predetermined, which could have led to problems in distribution. In an interview, Terry Jones later regretted editing this "prophetic" scene.

Otto's last appearance could not be eliminated: When Brian's mother and Judith visit the crucified Brian, the corpses of the "flying suicide squad" can be seen on the ground and with bobbing feet during the final song. Nevertheless, the pythons were exceptionally satisfied with the finished film. Michael Palin summarized: "We actually had the feeling that we had climbed one step with The Life of Brian ."

synchronization

The German synchronization was created in 1980 in the studios of Berliner Synchron . Arne Elsholtz was responsible for the script and dubbing . When casting the individual voices, Elsholtz refrained from assigning only one German speaker to each of the actors, who usually act in several roles. This decision led to John Cleese being dubbed in his various roles by a total of three speakers, who in turn spoke several roles of other actors (see table below). Some pythons in the stoning scene played women disguising themselves as men. In the German version, the male female actors are also spoken by women. Pontius Pilatus, who cannot articulate the "r" in the English original, struggles with the "B", "D" and " Sch " sounds in the German version .

| actor | Voice actor | Roll) |

|---|---|---|

| Graham Chapman | Uwe Paulsen | Brian / Schwanzus longus |

| Graham Chapman | Harry Wüstenhagen | 1. Wise men from the Orient |

| John Cleese | Thomas Danneberg | Reg / Jewish officer / centurion |

| John Cleese | Hermann Ebeling | Arthur |

| John Cleese | Uwe Paulsen | 2. Wise men from the Orient |

| Michael Palin | Harry Wüstenhagen | Pilatus / Turnip Nose / Francis / Ex-Leper / Ben / Boring Prophet / Disciple / Nisus Wettus |

| Michael Palin | Thomas Danneberg | 3. Wise men from the Orient |

| Michael Palin | Mogens von Gadow | Eddie |

| Eric Idle | Arne Elsholtz | Loretta / Singer Crucified / Bargainers / Warris / Otto |

| Terry Jones | Ulrich Gressieker | Brian's mother / crucifixion assistant |

| Terry Jones | Arne Elsholtz | Simon, the saint in the pit |

| Terry Gilliam | Joachim Tennstedt | spectator |

reception

Resistance before publication

During the filming, a ruling in the United Kingdom caused a sensation and subsequently a cause for concern among all those involved in the project: the religious organization Nationwide Festival of Light won its first conviction for blasphemy in 55 years in the country's courts. Not only was the publisher of the homosexual magazine Gay News sentenced to nine months in prison for publishing a blasphemous poem (the sentence was later commuted to a fine): the highest legal authorities confirmed the legal opinion that there is no need to commit blasphemy, in order to be condemned for acts of blasphemy against religion and God.

Work on the film was ongoing when the Nationwide Festival of Light acquired several script pages. Under the leadership of chairwoman Mary Whitehouse was mobilized against Life of Brian . A letter to the chairman of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) warned: "You yourself know the consequences of insidious abuse of God, Christ and the Bible." An opinion from attorney John Mortimer, with whom the Pythons finally put the film for examination The BBFC considered the possibility of a lawsuit to be slim. In addition to the basically harmless script, Mortimer also highlighted the popularity of the comedian troupe. The passage, according to which the scenes of the ex-leper and the question of Mandy's virginity could hurt religious feelings, he edited at the request of the Pythons in his assessment submitted to the BBFC.

The book on the film, which, in addition to the script, contained a few deleted scenes and was supposed to be sold in time for the premiere, offered a much larger target than the finished film. Publishers in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada long struggled with the decision of whether and how the book could be published. Above all, experts described the scene with the ex-leper complaining about Jesus as a “damned benefactor” as problematic, and a scene in the appendix to the book: In it a woman has to explain to her boyfriend that she has slept with someone who appears to be " Holy Spirit " issued. After consultation, the pythons regularly refused to make changes. When the film was released in the United States and Canada, later also by the BBFC, with no further concerns about possible blasphemous content, the publishers decided to publish Monty Python's Life of Brian (of Nazareth) / Montypythonscrapbook in view of the upcoming premieres . However, the commissioned English printer refused to print the controversial appendix, which is why the English first edition had to be produced by two printers.

Premieres

controversy

United States

The first performance of the film, which was controversial for insulting religion even before it was released, took place on August 17, 1979 in New York's Cinema One . The film was only released for children under the age of 17 when accompanied by an adult (“ Restricted ”). The reason for holding the premiere in the USA was not least due to the constitutionally enshrined freedom of expression .

Immediately after the publication, there were some angry reactions from Jewish , Catholic and Protestant associations. Orthodox Rabbi Abraham Hecht , president of the Rabbinical Alliance of America , expressed concern two days after the premiere of the film that the film was so offensive that "further performances could lead to outbreaks of violence." The fact that the first clear comments came from the Jewish side surprised the pythons, who had excluded attacks on Judaism in the final film. According to Terry Jones, it turned out that the main reason for this was the use of a Jewish prayer shawl that John Cleese wears in the stoning scene as a high priest . Other representatives of Judaism, on the other hand, described Hecht's statements as "a danger to freedom of thought".

Christians soon began to express dislike of the film: in a national radio commentary, Protestant Robert E. A. Lee described Life of Brian as "a heinous and disgusting attack on religious sentiments." The New York Archdiocese of the Roman Catholic Church considered the comedy to be an "act of blasphemy" for deriding the person of Christ. Father Sullivan of the Roman Catholic Office for Film and Broadcasting had expected a youth ban and considered it a sin for Catholics to watch the film.

Attempts by the Citizens Against Blasphemy Committee to initiate criminal prosecution were unsuccessful. To this end, Jews and Christians of various denominations met on September 16 in front of the Warner Bros. headquarters for a protest march to the premiere cinema, Cinema One . Posters read that Life of Brian was "a vicious attack on Christianity". In a speech, Rev. Roger Fulton commented on the “amoral aspects” of the film: “In direct contradiction to the Holy Scriptures, the mother of the Messiah (Brian) is portrayed by a man in women's clothes, [...] Male desires are repeatedly expressed given to transform into a woman. "

After Richard Schickel stated in his benevolent film review in Time Magazine that this aggressive satire was good for questioning one's own convictions and values, columnist William F. Buckley countered him with the question in the New York Post : “Does Mr. Schickel mean , we need a holocaust every now and then ? Or, should we just have to do without a Holocaust, should the people of Monty Python at least make a comedy about Auschwitz ? [...] "

The sometimes sharp debate broke away from the content of the film itself in that most of the critics and activists had not seen Life of Brian and trusted the accounts of others. According to Hewison, it was even rumored that a child was mistreated while filming.

When the film was released nationwide in September and October, some cinema operators did not include the comedy in their programs out of consideration for protests. Life of Brian caused a lot of excitement especially in the states of the so-called " Bible Belt " in the southeast of the United States. In Columbia , South Carolina , Republican Senator Strom Thurmond campaigned to have the film disappear from local theaters. The dismissal was followed by angry protests with placards such as "Resurrect Brian, crucify the censors". In most cities in Louisiana , Arkansas and Mississippi , screenings were canceled or canceled after prosecutors threatened lawsuits against cinema operators or the pressure of religious protests became too great.

Other church associations, on the other hand, took a markedly liberal stance. Whether protests took place and how the cinema operators reacted to them mostly depended on local sensitivities. The vast majority of the country's cinemas were able to show the film without any problems and, thanks to protests that attracted the attention of the media, enjoyed high revenues. The premiere cinema Cinema One, for example, recorded record revenues.

United Kingdom

At the end of August 1979, when the film was already running in the United States, the BBFC made its decision to release Life of Brian from the age of 14 without further complaints (certificate 'AA'). However, the recommendations of the BBFC do not have to be adopted by the respective English municipalities. With regard to the recommended age rating, which can be determined by each local council itself, the film distribution company CIC decided on a strict regulation: The film would not be shown in communities that banned the film from young people.

Meanwhile, the Festival of Light tried to prevent or at least severely limit screenings. So that the income from the "sick" film, which constantly fluctuated between "sadism and utter stupidity", did not increase because of public protests, as in the United States, the method chosen was to convince local bodies of a film ban. A complaint of blasphemy was also no longer in the room for the time being: the chances of success in court seemed too low. For the premiere on November 8, 1979 at the Plaza Cinema in London , demonstrators gathered in front of the cinema and sang hymns. On November 9, the Archbishop of York , Stuart Yarworth Blanch , called on all Christians and concerned citizens to warn local authorities about the film, “as in other cases where a film appears to be the Humanity devalues [...] ”.

On the evening television program Friday Night Saturday Morning on November 9, John Cleese and Michael Palin discussed in a studio audience with the Bishop of Southwark , Mervyn Stockwood , and Malcolm Muggeridge , a noted writer and revivalist . Muggeridge described how the film mocked the " Incarnation of God " as "cheap and flabby" ; Stockwood called any claim that Brian did not refer to Jesus "bullshit" from the start. Muggeridge was particularly outraged by the "repulsive" final scene in which "a lot of crucified [...] sings a revue number". Palin was visibly taken and irritated by the statements. He insisted that comedy did not want to divert people from faith, but only wanted to entertain: “Many leave the cinema happily and laugh at it. . Without that their faith has been shaken, "Bishop Stockwood played yet in his closing remarks to the Judaslohn to:" You get your 30 pieces of silver, I'm sure. "

It wasn't until the beginning of 1980 that Life of Brian hit cinemas nationwide. The rental company CIC hoped in advance that by then the accusation of blasphemy would be sufficiently invalidated. In addition, a collision with the Christmas holidays should be avoided. However, as in the United States, the national distribution controversy took off again. Bishops of several English cities protested, and the Festival of Light provided the Church of England with material against the film, which was distributed.

Several English municipalities have banned the performance of young people without having seen the film, such as in West Yorkshire or East Devon , where a city council justified itself: "You don't have to go to a pigsty to know it stinks." The bans were followed by protests against censorship and for freedom of expression. In the end, ten of the more than 370 municipalities were in favor of a ban and 27 for an X rating , which means that the film could not be shown due to the requirements of the distributor. This only harmed the spread of the comedy to a limited extent: again other neighboring communities allowed the comedy, mostly even without having checked it beforehand. As in the United States, the controversy fueled the box office success of Life of Brian .

Other states

In Canada , the coming conflicts first began to appear in June 1979 when a radio show about the making of Life of Brian was banned from being broadcast. The film itself passed the censors with no further blasphemy concerns. However, for the first time on the advertising material for the film, in addition to the age rating ("Restricted" - from 17 years accompanied by an adult), the additional warning that the film could offend religious feelings. The Sault Ste. The prosecutor did not allow Marie to be heard by a clergyman against the local cinema.

In Australia , Life of Brian kept parliament busy after a Roman Catholic priest in Queensland tried to get the censors to ban the film, but they refused. The Minister of Culture confirmed the legal opinion of the censorship authority, but said that the "grubby and tasteless" film should not be widely used if possible. Not least thanks to the excitement, Brian became one of the ten most successful films in the country. In Ireland , according to Hewison, attempts to get Brian through the censorship authorities failed to materialize from the start. However, the soundtrack, a radio play version of the film edited by the Pythons, could be introduced without any problems due to a legal loophole. When a popular television preacher drew attention to the record by saying, "Anyone who finds this record [...] funny must be disturbed", the sales department was forced to stop imports after newspaper reports, protest letters and threatening phone calls.

In Italy , the film did not hit theaters for unknown reasons. In his exact chronology of the controversy in Monty Python: The Case Against, Hewison could only guess whether this can be explained by the country's Catholic tradition . In Spain , France and Belgium , also strongly Catholic, there was no major resistance to the performance. The film was also approved in Austria , Germany , Switzerland , Greece , Denmark , Sweden and Israel without any problems.

The Norwegian censorship agency made a novelty when it banned a comedy for the first time in the country's history, Life of Brian . As a result, cinemas in neighboring Sweden advertised: “The film is so funny that it was banned in Norway.” In fact, the Norwegian censors justified their decision with the fact that the mass crucifixion at the end, but also the Sermon on the Mount at the beginning of the film could offend religious feelings. The surprising ban caused a stir in the media, and the film censors themselves tried to find a compromise together with the Norwegian film distributors. The Pythons did not agree to the suggestion to fade out the image during the crucifixion scene and only let the sound track run. Six months later, the unchanged film was finally allowed to be shown, as usual, in the original version with Norwegian subtitles - with the only restriction not to translate contentious passages.

Secular criticism

Film reviews in the secular press were also largely devoted to the controversy, for which many film critics showed understanding. Richard Schickel said that Life of Brian was anything but a "tame parody" and speaks of an "attack of the pythons on religion". Roger Ebert , for example , who joined Stanley Kauffmann of the New Republic , expressed contradicting views , according to which Christ would have enjoyed the film very much: " Life of Brian is so amusingly harmless that it is almost blasphemous to take him seriously."

Many film critics agreed that Life of Brian made fun of Bible films rather than Jesus. But when it came to assessing the quality of the comedy, the opinions of the film critics differed greatly. Americans not only seemed to have problems with British accents, as complained about by the industry journal Variety . The American critic Roger Ebert also said: "The strange, British humor of the troupe is sometimes difficult for Americans to access."

Regardless of this, Richard Schickel (Time) and Vincent Canby ( New York Times ) enjoyed the comedy: “The film is like a hovercraft, filled with strange energy”, which sweeps over some weak spots regardless.

In the Canadian magazine Maclean’s, Lawrence O'Toole agreed with those who found the film insulting, but “more because of its banality than its blasphemy.” In his review in Der Spiegel , Wolfgang Limmer expressed himself similarly: The religious excitement was too much for “a weak person Movie. Because the once wicked and bizarre joke of the Monty Pythons has degenerated into flawed, boring slapstick. ”With gags on the“ level of pubescent toilets ”, Life of Brian is “ a sad obituary for the Monty Pythons ”.

aftermath

As a direct result of the film's good reception by the audience, the comedy Wholly Moses! which was released in 1980 with Dudley Moore in the lead role. The Pythons themselves took advantage of the offer to produce their next film for the Hollywood studio Universal . While working on Monty Python's Meaning of Life , they had four times the budget they spent on Life of Brian , but the team spirit that had recently rekindled could no longer materialize; it remained the last joint film project of the style-forming comedian troupe.

Even decades after its completion, Life of Brian's audience success is considerable. In 2006, a Channel 4 poll showed Life of Brian as "the best comedy of all time". An online poll conducted by the British television magazine Radio Times in 2007 named the comedy “the best British film of all time”. The British Film Institute voted The Life of Brian # 28 in 1999 for Best British Films of All Time . Phrases and quotes - such as "Everyone only has one cross" or "He said Jehovah" - found their way into everyday culture.

Eric Idle's final song developed a successful life of its own: Always Look on the Bright Side of Life , as far as can be ascertained, made its way from English football stadiums to the hit parade: In 1991 the song took second place in the UK. The song also reached number two in the Austrian charts. Instead of pictures of the crucified, which are still taboo, the music video shows scenes from Monty Python's Flying Circus . In a 2007 interview, Eric Idle stated: "The song is one of the ten most requested funeral songs of the last 15 years." Together with the composer John Du Prez , Eric Idle created the oratorio Not the Messiah . The work is based on the film, includes the famous song, and premiered in June 2007 at the Luminate Festival in Toronto.

The extraordinary success and the controversy surrounding Mel Gibson's film The Passion of the Christ offered the Pythons a good opportunity to Life of Brian to get back into the cinemas of 2004. The satire was found refreshing by critics after 25 years: "Exactly what The Passion of the Christ was missing: More singing and dance numbers." The New Yorker expressed that in Life of Brian there was "not a bit of blasphemy." The online magazine kath.net , on the other hand, described Life of Brian as a film that makes fun of the suffering of Jesus and is considered “blasphemous” by many Christians.

The Welsh town of Aberystwyth has long believed that there was a performance ban. When actress Sue Jones-Davies (Judith), who was elected mayor of the city in 2008, campaigned for this alleged performance ban to be lifted, it turned out that although a committee in County Ceredigion was reviewing the film in 1981 and parts of it were "all." unacceptable ”, but the performance was still allowed. This was followed by a special performance in Aberystwyth with the participation of Terry Jones and Michael Palin.

Life of Brian occupies a prominent place in public debates about the freedom of art and especially satirical humor . In 2001, the British comedian Rowan Atkinson protested against stricter penalties for criticizing religion, which are contained in the new anti-terror law, with reference to the comedy of the Pythons.

In the 2006 debate in Germany about the satirical cartoon series Popetown , the media and those involved also referred to Life of Brian . Some observers and commentators have drawn parallels to the controversy surrounding the Life of Brian and the Mohammed cartoons . The Pythons themselves are skeptical as to whether a film like Life of Brian could be made these days. "Today everyone would think twice about it."

In October 2011, the BBC commissioned television film Holy Flying Circus , which satirically tackles the 1979 controversy, was broadcast.

A member of the Religious Freiheit im Revier initiative has been organizing a public performance of the film on Good Friday in Bochum since 2013 . In the opinion of the Hamm Higher Regional Court, this is a violation of Section 6 of the Public Holidays Act in North Rhine-Westphalia . It therefore imposed a fine against which the person concerned had lodged a constitutional complaint. This was rejected by decision of December 6, 2017 because the applicants failed to apply for an exemption. The film is still classified by the Voluntary Self-Control of the Film Industry (FSK) as “not free of public holidays”.

Film analysis

Staging

dramaturgy

The life story of Jesus Christ known from the Gospels serves as the framework and subtext of Brian's story: "Both stories begin with a birth in the stable and head towards the crucifixion at the behest of Pontius Pilate." According to W. Barnes Tatum, Life of Brian can thus lead to Tradition of the Jesus films are counted, the motifs of the New Testament narrative reflected and reinterpreted. Unusually, this alternative story runs parallel to that of Jesus. Jesus himself only appears at the beginning of the film, also to make it clear that Brian does not mean Jesus, although there are clear parallels between the two.

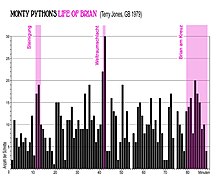

Life of Brian is considered to be the best structured film from comedian group Monty Python. In contrast to previous or subsequent productions, the individual Python-typical skits are subordinate to the course of the story. In this, Brian is first involved in a Jewish resistance group, is then arrested, and is then most of the time on the run - first from the Romans, then from his spiritual supporters. The final, about 20-minute long crucifixion sketch interweaves several smaller skits in which all the main characters appear. The only irritation within the otherwise coherent dramaturgy is the sudden appearance of a spaceship occupied by aliens. To Tatum it seems as if "the troops could no longer hold back". James Berardinelli, however, sees Brian's sudden rescue by a spaceship parodying the usual deus-ex-machina conventions of common film dramaturgy. In the opinion of many film scholars, the closing song Always Look on the Bright Side of Life , which the crucified ones sing, expresses the philosophical attitude of the film and the entire work of the Monty Pythons in the text.

Visual style

In his review of the revival, Rob Thomas (Capital Times) states that Life of Brian looks so much like a classic Bible epic that one is "almost shocked to see John Cleese's eyes flash out from under a Roman helmet". In fact, the team headed by production designer Terry Gilliam went to great lengths to capture the most realistic and believable atmosphere of the time. Dirt and grime are just as important a creative means as the laundry on the clothesline, which is often present in the scene, and which should convey activity in the settings.

The ambition to shoot a “heroic epic”, however, had its limits. It is true that director Terry Jones attached importance to the genre-typical aesthetics of rich colors and also broke with the idea of photographing comedies as brightly as possible: The sketch in which a centurion catches Brian smearing the palace walls and giving him tutoring in Latin grammar takes place in the dark instead of. Apart from that, original or epic-looking recordings were largely avoided in order not to distract from the comedy. "The camera was positioned like on a television show," said production designer Gilliam with discomfort, because his elaborate sets are hardly visible.

Terry Gilliam also tried to get around this “limitation by comedy” as much as possible by taking as far as possible camera positions of the surroundings on his own initiative in order to convey a feeling of grandeur: “If you get the big settings right, they have an effect and you can concentrate on the story… ”Close-ups were avoided as a matter of principle, because in comedies you have to see the relationship between the characters in as one shot as possible. Terry Gilliam: “We don't zoom in on everything. We don't make extraordinary attitudes. It's a comedy. At least that's our theory of comedy, and we're sticking to it. "

style

To this day, the Pythons do not share the view of many film critics that Life of Brian was a parody of Bible films or the like. In the film magazine Schnitt, Florian Schwebel agrees with this view: "Actually obligatory plot elements perfect for pasties such as temptations, betrayal by a disciple or the resurrection are not even made fun of." Terry Jones suspects that Life of Brian seems parodistic because the characters in it In contrast to classical Bible epics, maintain an emphatically everyday manner of speaking. Even in the development phase, Eric Idle described the project as a “biblical comedy”: The group wanted to deal with the biblical myth that shaped the western world in a humorous way.

James Berardinelli describes the typical Python style as a mixture of "clever, insightful humor with pithy dialogues and blatant silliness." The different styles that the six authors and actors bring to the table often seem to make it difficult for critics and film scholars to describe the effect . The Capital Times read: “Some of the jokes are on a fairly pubescent level, such as Pontius Pilate's speech impediment. Others are remarkably witty, for example when a crucified man does not want a Samaritan in the 'Jewish area'. "

Andrea Nolte notes in her review for Reclam a “lack of subtlety”, but at the same time praises the “range of comical characters, some of which are among the most subtle and best that the pythons have ever invented.” For example the ex-leper, the complained about the miracle of his healing because it deprived him of his source of income as a beggar. Or the centurion who gives Brian a tutorial in Latin instead of arresting him for his anti-Roman graffiti .

According to Michael Palin's observation, the typical “school humor” of the pythons comes into play in the aforementioned scene: teachers and other persons of authority are often the target of ridicule in the work of the Monty Pythons. John Cleese, who mainly wrote this sketch, himself worked as a Latin teacher for two years. “This is John as he lives and breathes. He has the wonderful ability to be able to write scenes from his emotional life that actually have a meaning, "said Idle, who sees the strengths of the other authors more in dealing with foolishness. John Cleese, on the other hand, suspected that he had adopted a lot of the style of Jones and Palin in this sketch, who often discussed absurd arguments about completely unimportant things.

Many discussions speak of “obscene disrespect”. But in the center of the satire, which apparently shows so much joy in breaking taboos, there seems to be just as much seriousness: "[...] the otherwise so gifted blast Graham Chapman plays nothing but confusion and suffering until the last Homeric laugh ."

Themes and motifs

Bible

The depiction of Jesus in two short scenes at the beginning of the film is strongly based on Christian iconography : The resistance fighters left the literal Sermon on the Mount angry because Jesus was too peaceful for them: "Obviously, pretty much everyone is blessed who has a personal interest in maintaining it of the status quo […] “Beyond the respectful portrayal of Jesus, the film does not suggest, in the opinion of most of the recipients, that there is no God or that Jesus is not God's Son. The appearance of a leper healed by Jesus confirms the Gospels, according to which Christ performed miracles.

After the introductory scenes, any direct reference to Jesus disappears, but his life story partly serves as a framework and subtext of Brian's story. The fact that Brian is the illegitimate son of a Roman could allude to the polemical legend that Jesus was the son of the Roman soldier Panthera . Brian himself speaks when he has to pretend to be a prophet, of the "lilies in the field" or articulates clearly: "Do not judge others that you will not be judged." The assumption that Brian repeats incoherently what he says about Picked up on Jesus is obvious.

In addition to Jesus, there is another person named in the Gospels : Pontius Pilate degenerates into “an absolute joke” in the film. Although there are allusions to Barabbas in the run-up to the crucifixion , there is no figure in Life of Brian that corresponds to Judas or Kajaphas . “Whether intended or not, the decision not to play Kajaphas prevents the possibility of viewing the film as anti-Semitic.” That the crucifixion, a main motif of Christian iconography, is viewed from its historical context within the narrative of the film and as routine mass crucifixion carried out is staged, caused irritation among devout Christians.

Faith and Dogmatism

According to consistent observations by film scholars and statements by the pythons, the declared aim of the satire is not Jesus and his teaching, but religious dogmatism. The Sermon on the Mount at the beginning of the film makes this approach clear: It is not just the poor acoustics that make it difficult to understand what Jesus said. The audience failed to interpret what was said correctly and meaningfully: When Jesus said “Blessed are the peacemakers”, the audience understood the phonetically similar “Cheesemakers” and interpreted this in turn as Metaphor and beatification of all who “produce dairy products”.

For the purposes of the philosopher David Hume satirizes Life of Brian the strong tendency of people to believe in the extraordinary and fantastic. When Brian breaks off his sermon and turns away from the audience, the crowd takes it to mean that Brian does not want to reveal the secret of eternal life and follows him every step of the way. In their need to submit to an authority, the crowd proclaims Brian a prophet and then a messiah. The faithful gather en masse under Brian's window to receive a divine blessing. Here Brian expresses the core message of the film according to consistent information: “You shouldn't follow anyone. You should think for yourself. ”When many believers protested against Life of Brian after the publication , the pythons saw this core statement of the satire confirmed.

Terry Jones said that Life of Brian “is not blasphemy, but heresy ” because it goes against church authority while believing in God remains intact: “Christ says all these wonderful things about peace and love, but bring them for two thousand years People turn to each other on his behalf because they can't agree on how or in what order he said it. ”When the followers argue over the correct interpretation of a sandal that Brian lost, Terry Jones said“ the story of the Church in three minutes. ”Kevin Shilbrack was also of the opinion that one could actually be“ pious and still be completely happy with the film. ”

The fact that dogmatism in the ranks of the political left is the target of ridicule has mostly been overlooked in the controversy. According to John Cleese, an unmanageable number of left-wing organizations and parties emerged in the United Kingdom that fought each other rather than their political opponents - because it was so important to them that “their teaching was pure”. The leader of the “Popular Front of Judea” makes it clear in the film: “The only ones we hate even more than the Romans [...] are those from the shit“ Judean Popular Front ”” idiot revolutionaries ”ended up presenting Brian on the cross with an elaborate explanation instead of saving him. So they indirectly accept the occupiers and their methods of execution as a fate to be endured.

Little attention was paid to the swipe at the women's movement that began to attract attention in the 1970s. Resistance fighter Stan wants to use - in the language of political activists - "his right as a man" to be a woman. Because no one should be deprived of the right to have babies, the group now continuously accepts him as “Loretta”. In addition, as a result, “siblings” instead of “brother” or “sister” prevailed as the new language rule.

Individualism and futility

Brian's large following followed him to the bedroom window. Irritated by the veneration she shows him, he explains to the faithful crowd: “You don't need to follow me. You don't need to follow anyone. You are all individuals. [...] Don't let anyone tell you what to do. "

According to Edward Slowik, this much-received scene is “undoubtedly one of those rare moments” when the pythons “openly and directly express a philosophical concept”. The television series Monty Python's Flying Circus , for which the comedian group formed in the late 1960s, was based in its understanding of humor on individualism and maladjustment. Life of Brian sums up the existentialist view that everyone has to give meaning to their own life.

Brian can therefore be described as an existentialist in the tradition of Friedrich Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre : He is sincere towards himself and others and leads, as best he can, an “authentic life”. However, Brian is too naive to be considered a hero in the spirit of Albert Camus . In Camus' view, the search for the meaning of one's own life takes place in a deeply absurd, meaningless world. The "absurd hero" rebels against this pointlessness and remains true to his goals, although he knows that his struggle will have no effect in the long term. Brian, on the other hand, is unable to see the pointlessness of his situation and therefore cannot triumph over it.

Kevin Shilbrack in Monty Python and Philosophy is sure that the world is absurd and that every life has to be lived without a superordinate meaning is the basic conception of the film. The penultimate verse of the popular song Always Look on the Bright Side of Life would clearly express this message:

“For life is quite absurd

and death's the final word

You must always face the curtain with a bow.

Forget about your sin - give the audience a grin

Enjoy it - it is your last chance anyhow. "

"Life is absurd.

Death is the last word . Curtsy

when the curtain falls.

Forget the burden of sins - give the audience a grin.

Enjoy the last chance in this world."

The finale expresses that the executions are pointless. There is "no indication that their deaths have any meaning or that a better world awaits them."

At this level it could be said that Life of Brian represents a worldview that contradicts that of religion fundamentally: "The universe responds to the human search [for meaning and happiness] with silence." But Life offers a counterbalance to nihilism of Brian , according to Kevin Shilbrack, humor, which in turn is compatible with religion: "You can't fight senselessness, but you can laugh at it."

literature

Primary literature

- Monty Python: The Life of Brian. Screenplay and apocryphal scenes . Wilhelm Heyne Verlag (paperback edition), Munich 1994, ISBN 3-453-07154-9

Secondary literature

- Darl Larsen: A Book about the Film Monty Python's Life of Brian. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2018, ISBN 978-1-5381-0365-4

- Joan E. Taylor: Jesus and Brian. Exploring the Historical Jesus and his Times via Monty Python's Live of Brian . Bloomsbury T&T Clark, London u. a. 2015, ISBN 978-0-567-65831-9

- Gary L. Hardcastle and George A. Reisch (Eds.): Monty Python and Philosophy . Carus Publishing Company, Illinois 2006, ISBN 0-8126-9593-3

- Heinz-B. Heller and Matthias Steinle (eds.): Film genres: Comedy . Philip Reclam, Stuttgart 2005, pp. 381-384, ISBN 3-15-018407-X

- Monty Python, Bob McCabe: The Autobiography of Monty Python . Verlagsgruppe Koch GmbH / Hannibal, Höfen 2004, pp. 272–307, ISBN 3-85445-244-6

- W. Barnes Tantum: Jesus at the Movies . Polebridge Press, Santa Rosa 1997, revised and expanded 2004, pp. 149-162, ISBN 0-944344-67-4

- Andreas Pittler: Monty Python. About the meaning of life . Wilhelm Heyne Verlag, Munich 1997, pp. 152-162, ISBN 3-453-12422-7

- Kim “Howard” Johnson: The first 200 years of Monty Python . Plexus Publishing Limited, London 1990, pp. 205-213, ISBN 0-85965-107-X

- Robert Hewison: Monty Python: the case against . Eyre Methuen Ltd, London 1981, pp. 58-95, ISBN 0-413-48650-8

Web links

- Life of Brian in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Life of Brian at Rotten Tomatoes (English)

- Life of Brian at Metacritic (English)

- Brian's Life in the online movie database

- Brian's life in the German dubbing file

- Complete text script (German)

- Sound carrier with the film music

- Some scenes of the film on the Monty Python Channel on YouTube (in English original version: Romans Go Home , He's Not The Messiah , Stoning, Biggus Dickus, Hermit and Always Look On The Bright Side of Life ).

Individual evidence

- ^ Certificate of Approval for The Life of Brian . Voluntary self-regulation of the film industry , March 2003 (PDF; test number: 51 508 V / DVD).

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 59.

- ↑ See Michael Palin's commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 1.

- ↑ John Cleese's Commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 1.

- ↑ Michael Palin in Autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 279.

- ↑ a b See autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 280.

- ↑ Michael Palin's commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 28.

- ↑ a b c Terry Jones' Commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 21.

- ↑ Michael Palin in Autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 284.

- ↑ See Graham Chapman in Autobiography of the Monty Pythons , pp. 286f and Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 63.

- ↑ a b See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 64

- ↑ a b See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 65

- ↑ "[...] apparently for no more reason than that he wanted to see the film." Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 65.

- ↑ John Cleese's Commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 10

- ↑ See John Cleese's commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 3

- ↑ a b c See autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 281.

- ↑ Terry Jones in Autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 281.

- ↑ Eric Idle in Autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 290.

- ↑ See Terry Gilliam in Autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 286.

- ↑ a b Terry Jones' Commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 3.

- ↑ Michael Palin in Autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 290.

- ↑ a b c d e See Johnson, The first 200 years of Monty Python , pp. 206-212.

- ↑ a b Terry Gilliam's comment on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 13.

- ↑ See Terry Gilliam's commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapters 5, 7, 11.

- ↑ a b Terry Gilliam in Autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 287.

- ↑ Eric Idle's commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 10.

- ↑ " If anybody had walked on the set, they could have thought it was the fifth week. “Quoted in Johnson, The first 200 years of Monty Python , p. 207

- ↑ Michael Palin's commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 20.

- ↑ a b Terry Jones in Autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 294.

- ↑ Terry Jones' Commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 5.

- ↑ Michael Palin's commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 13. Michael Palin's suppressed laugh can be seen at around 0:40:00.

- ↑ Michael Palin's commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 10.

- ↑ See Terry Gilliam's commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 27.

- ↑ Quoted from Das Leben Brian , paperback edition, p. 91. Because George Harrison said nothing in the role, Michael Palin later dubbed a 'hello' - cf. Autobiography of the Pythons , p. 294.

- ↑ See page no longer available , search in web archives: Kim "Howard" Johnson's shooting report on pythonline.com (accessed on February 9, 2008); In his earlier book The first 200 years of Monty Python , Johnson writes of 750 extras (p. 208), which seems greatly exaggerated.

- ↑ Eric Idle's Commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD , Chapter 21.

- ↑ See Terry Jones' commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 21.

- ↑ Terry Gilliam's commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 7.

- ↑ a b Terry Jones' Commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 30.

- ↑ Terry Gilliam's Commentary on Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 30.

- ↑ See Eric Idle's commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 32.

- ↑ a b See Terry Gilliam's comment on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 9

- ↑ See Terry Gilliam's commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 7

- ↑ Terry Gilliam's comment on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 2

- ↑ a b c Terry Gilliam in Autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 293

- ^ Graham Chapman in Autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 291. See also Johnson, The first 200 years of Monty Python , p. 211

- ↑ Terry Gilliam's commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 9.

- ↑ a b See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 69.

- ↑ Quoted from Monty Python, Das Leben Brian , paperback edition of Heyne Verlag, p. 92.

- ↑ Terry Gilliam in Autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 298.

- ^ " I think what it addressed is extremely relevant today, with what's going on in Israel. Eric put his finger on something; it was quite prophetic. "(" Dt: I think what we were talking about back then is extremely relevant today to what is going on in Israel today. Eric [Idle] put his finger on something; it was very prophetic. ") Terry Jones in The Telegraph (accessed September 23, 2008). These and other scenes are available on the latest DVD edition of the film ( The Ultimate Edition ) . See article on fanonite.org ( Memento of August 4, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed September 23, 2008).

- ↑ Michael Palin in Autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 306.

- ↑ Thomas Bräutigam: Lexicon of film and television synchronization. More than 2000 films and series with their German dubbing actors etc. Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-89602-289-X , p. 264 / in the German dubbing index (accessed December 2, 2007).

- ↑ a b See Pittler, Monty Python , p. 158.

- ↑ https://www.synchronkartei.de/film/1908

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 61.

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 66.

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 67

- ^ Letter of February 19, 1979 to James Ferman, quoted in the documentation The Story of Brian , chapter 3

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 68

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , pp. 72-76.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Cf. Tatum: Jesus at the movies , pp. 151–162.

- ↑ "This film is so grievously insulting that we are genuinely concerned that its contiued showing could result in violence." Quoted in Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 78.

- ↑ See autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 300.

- ^ "Any attempt by any central group to impose a boycott is very dangerous for the freedom of ideas." Rabbi Wolfe Kelman, quoted in Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 79.

- ↑ "[...] a disgraceful and distasteful assault on religious sensitivity." Robert E. A. Lee, cited in Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 78

- ↑ "[...] holds the person of Christ up for comic ridicule and is, for Christians, an act of blasphemy." Quoted in Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 78

- ↑ a b See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 78.

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 79.

- ↑ "'The Life of Brian' [...] a vicious attack by Warner Bros. upon Christianity!" S. Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 79 and Johnson, The first 200 years of Monty Python , p. 212

- ^ "The mother of Messiah (Brian) is a man in woman's clothing, in direct violation of the Holy Scriptures. […] Several times male desires to change into a female are expressed. ”Cf. Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 80.

- ↑ See Richard Schickel's film review on time.com (accessed on February 18, 2008).

- ↑ "Is Mr Schickel saying that we should have an occasional Holocaust? Or is he saying that if we go for a stretch of time without a holocaust, at least we ought to engage the Monty Python players to do a comedy based on Auschwitz? With the characters marching into the gas chamber dancing, say, the mamba? Led by Anne Frank? ”Quoted in Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 81.

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 81. In his commentary on the film on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Terry Jones emphasized that there was no baby in the crib when Mandy beats it (Chapter 1 the DVD).

- ↑ It all started with a cinema operator in Brooklyn, cf. Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , pp. 81, 83.

- ^ "Resurrect Brian, Crucify Censors", cf. Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 82.

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 82

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 75

- ↑ a b c See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 86

- ↑ "Its theme is sick, its story veering unsteadily between sadism and sheer silliness." Raymond Johnston, director of the Festival of Light, in the Church of England Newspaper, Nov. 23, 1979, cited in Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , 84

- ↑ "[...] as in other cases where it seems that a film has been made which devalues humanity [...]." Quoted in Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 86.

- ↑ a b c Excerpts from the debate can be found e.g. B. in the documentation The Story of Brian , chapters 3–4.

- ↑ “You don't have to see a pigsty to know that it stinks.” Quoted in Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 89

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 90

- ↑ Robert Hewison names the amount of 4 million GPB, see Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 91

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 71.

- ^ "Warning - contents of this film may be offensive to those who have religious beliefs." Quoted in Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 72.

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 83.

- ↑ a b See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 92.

- ↑ "Anybody who buys the record and finds it funny must have something wrong with their mentality." Brian D'Arcy, quoted in the Irish Independent January 15, 1980, reproduced in Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 91

- ↑ a b c See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 91

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , pp. 92 f.

- ↑ “[…] this is no gentle spoof, no good-natured satire of cherished beliefs. The Pythons' assault on religion is as intense as their attack on romantic chivalry in Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975). " Richard Schickel in Time Magazine on September 17, 1979, p. time.com (accessed February 18, 2008).

- ↑ " Life of Brian is so cheerfully inoffensive that, well, it's almost blasphemous to take it seriously." Roger Ebert on rogerebert.com (accessed February 20, 2008).

- ↑ See e.g. B. Roger Ebert on rogerebert.com (accessed February 20, 2008) and Vincet Canby on movies.nytimes.com (accessed February 20, 2008).

- ↑ "[...] the troupe's peculiarly British brand of humor is sometimes impenetrable to Americans." Roger Ebert on rogerebert.com (accessed February 20, 2008).

- ^ "The film is like a Hovercraft fueled by comic energy. When it comes to a dry patch, it flies blithely over with no reduction in speed. " Vincent Canby on movies.nytimes.com (accessed February 20, 2008). Richard Schickel writes synonymously: "[...] the audience is always confident, even when things are running a bit thin, that good stuff will be along shortly." S. criticism time.com (accessed on 18 February 2008).

- ↑ "[... insulting] for reasons of banality rather then blaphemy." Quoted in Tatum: Jesus at the Movies , p. 161.

- ↑ Bastard on the cross . In: Der Spiegel . No. 33 , 2008 ( online ).

- ↑ See Hewison, Monty Python: The Case Against , p. 84.

- ↑ Oh, Moses! Internet Movie Database , accessed June 10, 2015 .

- ↑ See autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 311 ff.

- ↑ See the message on the BBC news website, news.bbc.co.uk (accessed March 23, 2008).

- ↑ See message on filmstarts.de ( memento of March 14, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed on January 31, 2008).

- ↑ See article about Life of Brian on the occasion of the revival in 2004 on heise.de (accessed on April 4, 2008). Even Tony Blair was referring unequivocally during a parliamentary debate on the well-known content of the film satire. A MP previously converted the film quote “What have the Romans ever done for us” to the government. See minutes of the June 2006 debate on theyworkforyou.com (accessed April 4, 2008).

- ↑ austriancharts.at, Austrian Charts: Always Look on The Bright Side Of Life (accessed on September 10, 2012)

- ↑ See autobiography of the Monty Pythons , p. 298.

- ↑ Eric Idle in The Story of Brian , Chapter 2.

- ↑ See message page no longer available , search in web archives: from May 28, 2007 on macleans.ca (accessed on March 29, 2008).

- ^ “See, this is what The Passion of the Christ needed. More song-and-dance numbers. " Rob Thomas, in the Capital Times of July 15, 2004, or on uk.rottentomatoes.com ( July 28, 2009 memento in the Internet Archive ) (accessed March 14, 2008).

- ↑ " Life of Brian contains not a shred of blasphemy." Anthony Lane, on newyorker.com (accessed March 14, 2008).

- ↑ See message on kath.net (accessed on March 17, 2008).

- ^ A b Carl Yapp: Python stars for special showing (with "Editor's Note", addendum from April 2009) ( English ) In: BBC News . February 27, 2009. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ From a report in the Frankfurter Rundschau dated October 17, 2001, accessed on March 17, 2008 at ibka.org .

- ↑ See e.g. B. tv diskurs 37, accessed on March 17, 2008 at fsf.de ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) as well as a comment in the Hamburger Abendblatt , s. Abendblatt.de (accessed on March 17, 2008).

- ↑ See reports and comments from February 8, 2006 on spiegel.de , February 6, 2006 on handelsblatt.com, February 17, 2008 on faz.net , as well as on qantara.de (all accessed on March 17, 2008) .

- ↑ Terry Jones in an interview for the documentary The Story of Brian , Chapter 4.

- ↑ Law on Sundays and Holidays ( National Holidays Act) in the version published on April 23, 1989. On :recht.nrw.de, accessed on April 14, 2017

- ^ Andreas Stephan: OLG Hamm: The life of Brian on Good Friday inadmissible. On: justillon.de, April 14, 2017

- ↑ Good Friday bans - cultural property or paternalism?

- ↑ "Both Jesus 'and Brian' stories begin with a lowly birth in a stable. Both stories move toward a crucifixion at the behest of Pontius Pilate […] “Tatum, Jesus at the Movies, p. 151.

- ↑ See Rob Thomas, in the Capital Times of July 15, 2004, or at uk.rottentomatoes.com (accessed March 14, 2008).

- ↑ a b See James Berardinelli on reelviews.net (accessed on March 14, 2008).

- ↑ a b c d e Reclam, Filmgenres: Komödie , pp. 382–384.

- ↑ "The one deviation, as though the troupe could contain themselves no longer, occurs midway through the film with a Star Wars moment when a spaceship suddenly rescues Brian." Tatum, Jesus at the Movies , p. 152.

- ↑ "The production values are so convincing that it's sometimes a bit of a shock to see John Cleese's beady eyes underneath a centurion's helmet, or Michael Palin's twinkle under a flowing beard." Rob Thomas, in the Capital Times of July 15, 2004, or at uk.rottentomatoes.com (accessed March 14, 2008).

- ↑ Terry Jones' Commentary on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 12.

- ↑ See Terry Gilliam's comment on the Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 1.

- ↑ Terry Gilliam's commentary on Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 21.

- ↑ Terry Gilliam's Commentary on Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 11.

- ↑ a b c Florian Schwebel in section - Das Filmmagazin # 47, March 2007, pp. 27, 28.

- ↑ Terry Jones' Commentary on Ultimate Edition DVD, Chapter 13.

- ^ "As always, the Pythons mix smart, insightful humor with pithy dialogue and outrageous silliness." James Berardinelli on reelviews.net (accessed March 14, 2008).