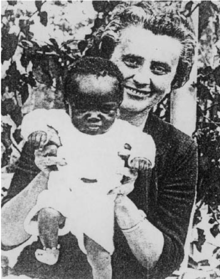

Johanna Decker

Johanna Maria Katharina Decker (born June 19, 1918 in Nuremberg ; † August 9, 1977 in front of St. Paul's Busch Hospital) was a German Catholic missionary doctor . She was murdered by terrorists on August 9, 1977 during the civil war in Rhodesia (today: Zimbabwe ).

Life

Johanna (nickname: Hanna) Decker was born as the daughter of the customs finance councilor Ignaz (1876–1947) and Maria-Anna Decker, née. Jäger (* 1884) born in Nuremberg . In 1922 her father was transferred to Amberg , where she attended elementary school and from 1928 to 1934 the Lyceum of the Poor School Sisters , which today bears her name: Dr. Johanna Decker Schools . She was an above-average student, was artistically gifted, was good at drawing and played the piano. In 1937 she graduated from secondary school in Amberg with her Abitur.

Decker was active in church youth work. Since then, she must have had the idea of joining the medical missionary service with which she came into contact in Würzburg , where she joined the Medical Mission Institute in 1939 . On the feast of Epiphany (January 6th) 1946, she made the oath to "dedicate herself to the missions in the heathen lands for at least 10 years after completing her medical studies".

After studying medicine in Würzburg and Munich, she trained as a specialist in neurology in Mainz . In 1950 she was sent from the Medical Mission Institute in Würzburg to Bulawayo in Rhodesia (today: Zimbabwe ). First she completed a long period of acclimatization in the hospital of the Fatima Mission. In 1960 she was then commissioned to set up the new Busch Hospital in St. Paul’s in the Lupane district of southwestern Zimbabwe (northern Matabeleland).

In collaboration with the Mariannhill missionaries , who took on the pastoral and economic care, Decker took care of the hospital. As the only doctor within a radius of 100 km, she and her team also looked after the seven outstations. Her presence on site also meant service in the clinic, and there was practically no private life. Within a few years a modern hospital with the associated infrastructure (apartments for the employees and student nurses) was built.

On August 9, 1977, early in the afternoon, there was a raid on St. Paul's. Two heavily armed terrorists entered the hospital through the main entrance. The two drunk blacks had previously murdered a chief on the way to the hospital, gouged out a man's eyes and beat patients on the hospital premises. In the ambulance room, they found Decker, who was examining and treating patients. She was supported by Sr. Ferdinanda Ploner ( CPS ), 53, who was born in Austria and had a South African passport. The two guerrillas asked for money and Decker gave them the contents of the cash register. However, this was not enough for the two insurgents. Decker told them she had more money in her house and went to get it. On the way to their house, the rebels opened fire from their Kalashnikovs without warning . Decker and Sr. Ferdinanda immediately collapsed dead. Decker had only received one fatal shot while Sr. Ferdinanda was hit by eight bullets.

Johanna Decker is buried in the city cemetery in Bulawayo .

Background and consequences of the act

Decker had always remained true to her calling and never strayed from the path. However, she must have had a vague premonition of the terrible events. As has been testified by many people, she cried a lot when she last said goodbye to Europe in autumn 1976 at the airport in Rome.

This was related to the murder of the diocesan bishop of Bulawayo Adolph Gregor Schmitt in December 1976. During the civil war, the (white) missionaries' facilities were a preferred target for terrorist attacks. The mission order of the Mariannhiller recorded a total of nine religious sisters killed in the period up to 1985.

The crime itself could never be solved and the perpetrators were never caught. R $ 400 (approximately £ 400) was reported to have been stolen in the raid. During the robbery, there are said to have been attacks on the black hospital staff. The sisters are also said to have been threatened with rape and around 130 patients are said to have been driven out of their beds. After Zimbabwe gained independence in 1980, a general amnesty was agreed for all crimes during the civil war in the Lancaster House Agreement . So the terrorist attack was never atoned for.

The hospital had to be closed after Decker and Ploner were murdered. A few months later it was looted and destroyed. After that, the site lay fallow for a long time. Today St. Paul's is run as the outstation of St. Luke's Mission Hospital. There are said to be plans to rebuild the Decker-built church on the site.

Meaning / awards / honors

She has earned an excellent reputation through her years of exceptional commitment and the great care with which she ran the hospital. In the literature she is also referred to as the martyr of the Medical Missions . But her death had neither medical nor theological causes. She paid for her job as a missionary doctor with her life because, for the sake of her job, she took a calculated risk in a weighing of interests: (medical) care for the people entrusted to her was more important to her than her own safety. She is still considered a great role model for all aspiring missionary doctors and is known beyond the borders of Zimbabwe and Germany.

Decker also made a name for herself as a scientist through a number of scientific articles in prestigious medical journals in South Africa , the UK and Germany. On November 29, 1979, she was posthumously awarded the Noristan Prize by the Pretoria Science Council. The University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland , which later became the University of Rhodesia and what is now the University of Zimbabwe , regularly sent young doctors and families to their hospital for training.

In 1981 a street was named after her in her hometown Heimstetten / Kirchheim near Munich . In 2006 a building of the Medical Mission Institute in Würzburg was officially renamed the Hanna Decker House .

Johanna Decker was included as a witness of faith in the German martyrology of the 20th century and in the ecumenical list of martyrs Witnesses of a Better World .

swell

Diaries, letters and other documents from Decker's estate are kept in the archive of the Mariannhill Missionaries in Rome, including numerous conversations and interviews with people who knew Decker (recorded by Adalbert Ludwig Balling and deposited in the CMM archive in Rome).

Fonts

- Central nerve diseases after peripheral injuries - with special reference to syringomyly, spinal muscular atrophy and amyotr. Lateral sclerosis . Diss. Uni. Munich, 1942.

- The mission doctor . In: Hippocrates 14/1963.

literature

- Adalbert Ludwig Balling : Dr. Johanna Decker . In: Helmut Moll (ed.): Witnesses for Christ. The German martyrology of the 20th century. Volume II. 7th, updated and revised edition, Schöningh, Paderborn u. a. 2019, ISBN 978-3-506-78012-6 , pp. 1707-1711.

- Adalbert Ludwig Balling: Johanna Decker . In: Karl-Joseph Hummel , Christoph Strohm (Hrsg.): Witnesses to a better world. Christian martyrs of the 20th century . Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Butzon & Bercker, Leipzig / Kevelaer 2000, ISBN 3-374-01812-2 / ISBN 3-7666-0332-9 , pp. 459–472.

- Adalbert Ludwig Balling, Heinrich Karlen: Johanna Decker . In: Mission magazine “mariannhill” , 6/1977.

- Adalbert Ludwig Balling, Helmut Holzapfel: Johanna Decker . In: Würzburger Sonntagsblatt , August 1977.

- Adalbert Ludwig Balling: No gods who eat bread, but builders of bridges between black and white . Missionsverlag Mariannhill, Würzburg 2001.

- Adalbert Ludwig Balling: Johanna Decker. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 19, Bautz, Nordhausen 2001, ISBN 3-88309-089-1 , Sp. 174-175.

- Wolfgang Leischner: Medical Missions in Rhodesia / Zimbabwe. On the history of the mission hospitals in the Archdiocese of Bulawayo and the biographies of their leading doctors . Dissertation, Julius Maximilians University of Würzburg , Würzburg 2004 ( full text ).

- Andreas Mettenleiter : Testimonials, memories, diaries and letters from German-speaking doctors. Supplements and supplements II (A – H). In: Würzburg medical history reports. 21 (2002), pp. 490-518, here: p. 499 ( Decker, Hannah ).

Web links

- Contemporary English language newspaper article in the Guardian (London) and Daily Telegraph (London) about the crime

- Barnabas Stephan: Dr. Johanna Decker ( biography )

- Short directory in the online version of the German Martyrology of the 20th Century ( Archdiocese of Cologne ).

Individual evidence

- ^ Andreas Mettenleiter: Personal reports, memories, diaries and letters from German-speaking doctors. Supplements and supplements II (A – H). Würzburg medical history reports 21 (2002), pp. 490-518; P. 499

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Decker, Johanna |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Decker, Hanna |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Catholic missionary doctor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 19, 1918 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Nuremberg |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 9, 1977 |

| Place of death | in front of St. Paul's Bush Hospital Zimbabwe |