La Noria

| La Noria | ||

|---|---|---|

|

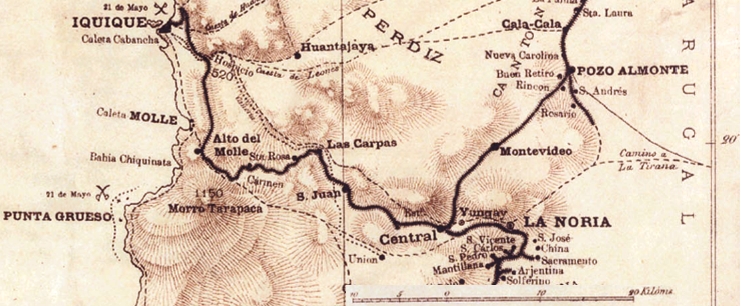

Coordinates: 20 ° 23 ′ S , 69 ° 51 ′ W La Noria on the map of Tarapacá

|

||

| Basic data | ||

| Country | Chile | |

| region | Tarapacá region | |

| Commune | Pozo Almonte | |

| Residents | 0 | |

| Detailed data | ||

| height | 983 m | |

| Children and residents on a street in La Noria around 1910 | ||

La Noria is a ghost town in the Atacama Desert near Iquique in northern Chile . It was the housing estate of the Oficina La Noria saltpeter works established in 1826 , which developed into a regionally important urban center with communal facilities and the seat of a civil administration. There were numerous mines and refineries in their immediate vicinity. It is one of the oldest factory settlements of the saltpetre industry, the ruins of which are still preserved.

geography

The ruins of the former mining settlement of La Noria are about 56 km southeast of the port city of Iquique . Today the place belongs to the municipality of Pozo Almonte ( 20 ° 15 ′ S , 69 ° 47 ′ W ) in the Región de Tarapacá , northern Chile.

La Noria is located in the Atacama Desert , in a valley on the eastern edge of the coastal cordillera. It is an inhospitable place with an extreme, hostile climate. It is very hot during the day, very cold at night, and often no rain falls for years. It is an extremely arid area, but it was relatively easy to get to groundwater. Hence the toponyms “noria” Spanish. Bucket wheel and “pozo almonte” Spanish fountain of Almonte . The capillary rising water evaporates quickly in the arid climate and over time left behind powerful salt crusts containing nitrates, the raw material for mining in the zone. In the absence of plants that would otherwise have consumed it like manure, the saltpetre could accumulate. The British naturalist William Bollaert described the place as follows in the mid-19th century:

“La Nueva Noria, 3227 feet [984 m] above the sea. Water boils at 206 ° F [96.6 ° C ]. Here there are two cities built from the salt of the Salare , one called La Noria and the other El Salar. Countless nitrate quarries can be seen in the sloping base of the hills and rolling terrain 50 to 150 feet above the salars, and obviously older than the salt in the salars. There is no nitrate in the salars. You can see the chimneys of the boiler smoking; the norias, for drawing water from the well. The scene is absolutely sterile, with piles of skeletons of mules and donkeys around the oficinas, or nitrate refineries. The water here has to be distilled to drink, but the animals drink from the well. If nitrate accidentally or deliberately gets into the drinking troughs, the animals are poisoned, swell up and perish. … In summer, when iron pieces are exposed to the sun, they get too hot to handle and dark stones are about the same temperature. This strong and radiant summer heat causes the stones to expand noticeably during the day and when they cool down at night they burst and their surfaces break off. … In the month of June, ice was observed 1/8 of an inch [approx 3 mm] thick. March 29, 1854, during the night it rained a little ... "

Around La Noria there are numerous historical saltpeter works, called oficina (Spanish: "office"). For example, the Oficina La China (laid out by Demetrio Figueroa in 1856), Oficina Limeña (laid out by George Smith in 1857 as Nueva La Noria), Oficina San José de La Noria (by Pedro Devéscovi and Arredondo), Oficina Santa Beatriz (operated by Pedro Elguera until 1881) and Oficina Paposo (1872–1931, created by Fölsch & Martín). There are considerations to develop the place for tourism, such as the Humberstone and Santa Laura saltpeter works , which are northeast of it at a distance of about 20 km as the crow flies.

Four kilometers south-east of La Noria there is still an open mine in operation .

history

Pre-industrial situation

Starting with the colonial history before the settlement was built, it can be said that the administration of the Spanish viceroyalty of Peru first became aware of the saltpeter deposits at La Noria in 1556. At first, however, silver mining in nearby Huantajaya ( 20 ° 14 ′ S , 70 ° 4 ′ W ) was much more interesting, so that in 1680 a Spanish mine operator named Juan de Loayza used the area around La Noria only to keep llamas . It was only after Thaddäus Haenke had invented a process for extracting potassium nitrate that a number of smaller saltpeter plants were set up in the region from 1810. The oldest were around 60 km further north in Negreira ( 19 ° 50 ′ S , 69 ° 52 ′ W ) and the second oldest in La Noria. The saltpeter obtained was known as Nitrato de Sosa or Nitrato de Iquique and was used for gunpowder production in Lima .

First saltpetre boom

In the turmoil of the Wars of Independence , many saltpetre factories were destroyed or abandoned. From 1821 La Noria belonged to the newly created state of Peru . The country opened up to foreigners. European naturalists and entrepreneurs began to be interested. The French trader Héctor Bacque († 1832) took the opportunity to rebuild the industry and founded the saltpeter factory Oficina La Noria in 1826 . After his sudden death, Irishman John O'Connor took over the management of Bacque's companies.

Provincial Governor Ramón Castilla commissioned the Englishmen William Bollaert (1807–1876) and George Smith (1802–1870) with the first systematic geographical and geological exploration of the Tarapacá region. Both came to La Noria in 1828 and reported that the place was infested with swarms of green flies and bed bugs . They registered a considerable salt crust there, which was only interspersed with other rocks on its surface.

The saltpetre factories in the region exported 900 tons of saltpetre in 1830. In the same year, a saltpeter ship set sail for Europe for the first time in the port of Iquique . Ironically, there were not enough buyers, so most of the cargo was dumped into the sea . But from 1834 the Chile nitrate became a sought-after raw material in Europe. In the beginning of the boom, George Smith acquired the La Noria plant in 1835 and ran it with a monthly saltpetre production of 23 to 27.6 tons.

In La Noria, the saltpeter works - like all the others - operated according to a simple but inefficient method. The crust of salt to be mined was a hard 7 to 8 foot thick layer of petrified sand, clay, and salt ( nitronatrite ). Some of the rock was blown up so that it could be recovered. It was broken into small pieces and treated with hot water on the spot in kettles until only the insoluble parts remained. The solution, the so-called nitrate liqueur , which contained sodium nitrate as its main ingredient, was then decanted into another vessel and concentrated either in the sun or over a fire . The solution was then allowed to cool and crystallize . The mineral so isolated was dried in piles in the sun. The dry powder was finally packed in sacks and transported on mules to the port in Iquique. In 1854 there were 100 such saltpeter works in the La Noria district. When the salt crust in one plant was broken down, the refinery was moved to the next salt station. Until 1850, the workers who raised and processed the natural resources were only housed in simple, small camps with no roads or supply facilities on the edge of the works. For shopping and entertainment, they went to the few places like La Noria that had shops, food stalls, canteens and brothels.

George Smith was an innovative entrepreneur and first introduced a new mechanical process in La Noria in 1856, in which the nitrate mineral was dissolved with hot water vapor. With this new technology, which required more complex installations, but delivered up to ten times better yield, the previously quite mobile saltpetre refineries became stationary plants to which the raw material was carted off even from a great distance.

A year later, Smith built a new saltpeter plant next to La Noria, called La Nueva Noria ("The New Noria"). In 1860 the La Noria plant was the largest of 40 in the Tarapacá region. In 1865 Smith sold everything he owned in Tarapacá. With it he mainly paid off accumulated debts. Englishman William Gibbs became the new owner of La Noria and Smith acquired a minority stake in the company. In the same year Gibbs was the first outside Europe to establish an iodine production facility in La Noria.

In July 1871 a railway line between Iquique and La Noria was completed. At that time there were around 25 saltpeter works in and around La Noria. The new transport option allowed the La Noria plant to increase production. In previous years the annual production was 9,200 to 10,150 tons, in 1871 and 1872 it was 13,800 tons each.

In 1872, the Fölsch & Martín company opened the Oficina Paposo plant next to La Nueva Noria . This extraordinarily successful company run by a Hamburg entrepreneur expanded with a further seven plants by 1881 and finally also took over overseas transport with its own shipping company.

In November 1873, La Nueva Noria was renamed La Limeña . That year La Noria had a population of 1,151, and the Limeña and La Noria plants supplied more than 46,000 tons of saltpetre.

Where there was so much to be earned, the dispute over control of the white gold , as it was called saltpetre , soon flared up . In May 1876, numerous saltpeter works were nationalized, including Paposo. In 1879 the so-called saltpeter war broke out between Chile, Bolivia and Peru. Chile prevailed and annexed the south of Peru and the coastal regions of Bolivia and thus incorporated La Noria into its territory.

urbanization

For La Noria and its 1154 inhabitants, the war was over in 1879. This year only three saltpeter works were still working there: Oficina Cholita (owner: Manuel Morales), Oficina Paposo (owner: Fölsch & Martín) and Oficina San Enrique . With the arrival of the Chilean administration, there were important innovations for the population and a new upswing in the saltpeter boom for entrepreneurs.

In 1880, the first public school in the entire province of Tarapacá was established in La Noria. It was a mixed school where the boys were taught in the morning and the girls in the afternoon. Mercedes Arantes was hired as the first headmistress and only teacher, with an annual salary of 800 pesos at the time. In the first year there were 50 students (35 girls, 15 boys) with an average attendance of 60%. Due to a change of residence and absenteeism for other reasons, only 20 of them completed the school year. In the second year the number of students increased to 85 and in the third to 155.

Also in 1880 a church was built in La Noria, but it was not officially consecrated until 1889. In this epoch the settlement reached the zenith of its development: It had become an important small town with a school, civil and criminal court, civil register, mine register, church, cemetery and train station.

The first downturn occurred with the discovery of more distant saltpeter deposits. As a result, La Noria gradually lost its role as the center of saltpeter mining and the terminus of the railway network. The rails were extended further south and north where the new saltpeter deposits were located. The nearby, rapidly growing settlement of Pozo Almonte became the new hub in saltpeter mining. The neighboring Oficina Paposo also had its own, well-organized factory settlement.

The 1885 census lists La Noria and Pozo Almonte as the two most important settlements in the saltpeter district of the Tarapacá province. The La Noria district had 4629 inhabitants (2918 male, 1711 female), of whom 1560 lived in urban areas and 3069 at other works. La Noria is not included in statistics from the same year, which recorded 165 workers for the Oficina Paposo. At that time there was probably no more work in La Noria itself, but the settlement still existed.

In 1897 there were 1,741 residents and in 1900 the civil registry for the La Noria district recorded 19 marriages, 20 births and 19 deaths.

Downfall

In November 1900, a fire destroyed several houses, including the no longer inhabited rectory. In 1901 production sank because the saltpetre content in the rock decreased. The workers were gradually laid off, who then left the place with their families. So La Noria was gradually depopulated and increasingly disintegrated. In 1902 the church was abandoned and the rectory was moved to the up-and-coming Pozo Almonte, where a new church had already been built. The church bells were given away to La Tirana ( 20 ° 20 ′ S , 69 ° 39 ′ W ).

While the church was halfway documenting their move, the school apparently broke up unnoticed. There is only an indirect indication of its closure from statistics from 1904 in which the school is no longer listed. It may have been closed many years earlier. It is known that the teacher Mercedes Arantes was in the village for over 15 years, i.e. left it after 1895.

In 1907 there were 9,938 inhabitants (2/3 men, 1/3 women) in the La Noria administrative district, more than twice as many as 22 years earlier. But all were classified as rural, that is, La Noria was no longer an urban district, but only a housing estate. In La Noria, 345 people were still counted. The population of the La Noria district was divided among the numerous saltpeter works. Oficina Cholita (383 people), Oficina San José (574 people), Oficina Sebastopol (244 people) were in the vicinity of La Noria. For comparison: 1064 people lived in neighboring Pozo Almonte.

The saltpetre industry suffered a drastic economic slump due to the First World War and the emerging production of synthetic saltpetre . The number of works decreased. While La Noria apparently disappeared unnoticed, the neighboring Oficina Paposo expanded. It was modernized and sold to the USA's Grace Nitrate Company in 1916. In 1920 Paposo was one of 31 working saltpetre factories. The police registered 880 people there, while La Noria is no longer mentioned in the same statistics. It looks like Oficina Paposo has absorbed the work and settlement of La Noria.

The Great Depression of 1929 caused the saltpetre industry to collapse and the Chilean state slid into its first and so far only national bankruptcy. This sealed the fate of the La Noria district. In 1931 operations in Paposo were discontinued, the associated factory settlement was abandoned and the school relocated to Macaya ( 20 ° 8 ′ S , 69 ° 11 ′ W ).

Decay and pillage

La Noria suffered the fate of many mining settlements that were built up during the boom and abandoned during the recession: abandoned by the owners, everything in the factories and settlements was looted that could still be used. According to a legend, two treasure chests are buried in La Noria, which have been lost there since the Saltpeter War, still inspires the imagination of looters to this day. Equipped with a pick and shovel, they don't even stop at the graves.

So the already forgotten place became known as the site of the Atacama humanoid . It is an extremely small human mummy that was excavated by a looter in La Noria in 2003 and finally sold to a so-called ufologist via a few fences . Since then, wild speculations have grown up about the place: extraterrestrials are said to come by there regularly, and the dead in the local cemetery come out of the graves at night.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ A b William Bollaert (1807–1876): Antiquarian, Ethnological, and Other Researches in New Granada, Equador, Peru and Chili. With Observations on the Pre-Incarial, Incarial and Other Monuments of Peruvian Nations . Tübner & Co., London 1860, p. 263-265 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ a b c Guillermo Billinghurst (1851-1915), Sergio González Miranda: Los capitales salitreros de Tarapacá . Biblioteca Fundamentos de la construcción de Chile, Santiago de Chile 2011, ISBN 978-956-8306-08-3 , pp. 109 ( cchc.cl [PDF; 9.1 MB ; accessed on May 19, 2013]). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ A b Ian Thomson: La Nitrate Railways Co. Ltda. La pérdida de sus derechos exclusivos en el mercado de transporte de salitre y su respuesta a ella . In: Historia . tape 38 , no. 1 , June 2005, ISSN 0073-2435 , p. 85-112 ( scielo.cl [accessed May 19, 2013]).

- ↑ Grau, Guillermo Thorndike: 1878 crimen perfecto . Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú, Fondo Editorial del Banco de Crédito del Perú, 2008, p. 524 ( books.google.de [accessed on May 22, 2013]).

- ↑ Chile. Ministerio de Hacienda (ed.): Memoria del Ministerio de Hacienda presentada al Congreso nacional . 1883, LCCN 10-024226 ( books.google.de [accessed May 22, 2013]).

- ^ A b Robert Krieg, Monika Nolte: Oro blanco - La historia . ( krieg-nolte.de [accessed on May 19, 2013]).

- ^ A b Miguel González P .: Maestros de la cirugía chilena: Dr. Oscar Contreras Tapia . In: Revista Chilena de Cirugía . tape 47 , no. 1 , February 1995, ISSN 0379-3893 , p. 8–12 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ a b c d According to Google Earth, May 12, 2013.

- ^ A b Edwin Gonzalo Lopez Pavez: El pozo de Almonte. (No longer available online.) Formerly in the original ; Retrieved May 20, 2013 (Spanish). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c d Juan Ricardo Couyoumdjian (1939 -): Una ciudad, una industria y un fotógrafo . In: Biblioteca Nacional (ed.): Album de las salitreras de Tarapacá / by L. Boudat y Ca. Santiago de Chile 2000, p. 4-7 ( memoriachilena.cl [accessed May 13, 2013]).

- ^ A b Mariano Eduardo de Rivero Ustariz: Noticia sobre el salitre y el borato de cal de Iquique. Extracto de las memorias de agricultura y economía rural de Paris. Año de 1854 . In: Colección de memorias scientificas agricolas é industriales publicadas en distintas epocas . H. Goemaere, Brussels 1857 ( books.google.de [accessed on May 12, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c d Ronald D. Crozier: La industria del Yodo 1815-1915 . In: Historia . N ° 27, 1993, ISSN 0717-7194 , p. 141–212 ( revistahistoria.uc.cl [accessed May 14, 2013]). revistahistoria.uc.cl ( Memento of the original from January 8, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Jaime B. Rosenblitt: El comercio tacnoariqueño durante la primera de vida década republicana de Perú, 1824-1836 . tape 41 , no. 1 , June 2010, ISSN 0717-7194 , p. 79–112 ( scielo.cl [accessed May 19, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c William Bollaert (1807–1876), Horacio Larrain B .: Descripción de la Provincia de Tarapacá . In: Norte Grande . tape 1 , no. 3 -4 (March to December). Santiago de Chile 1975 ( ucb.edu.bo [PDF; 6,6 MB ; accessed on May 19, 2013]). ucb.edu.bo ( Memento of the original from May 18, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Eugenio Garcés Feliú: Las ciudades del salitre - un estudio de las oficinas salitreras en la región de Antofagasta . Impresos Esparza, Santiago de Chile 1999, ISBN 956-7643-04-0 , p. 145 ( memoriachilena.cl [accessed May 12, 2013]).

- ↑ a b Ingrid Garcés M .: Evolución de la tecnología de la industria salitrera. Desde la olla del indio hasta nuestros días. (PDF; 1.0 MB) Accessed May 20, 2013 (Spanish).

- ↑ a b c d Paul Spaudo Vasquez: Pozo Almonte. La ciudad del futuro en busca de su identidad . Pozo Almonte ( liceoasgg.cl [PDF; 1.3 MB ; accessed on May 19, 2013]).

- ^ A b Sergio Fernández Larraín (1909–1983), Guillermo Izquierdo Araya (1902–1988), Rodrigo Fuenzalida Bade: Departamento de Tarapacá. Aspecto jeneral del terreno, su clima i sus producciones . In: Boletin de la guerra del Pacifico, 1879–1881 . Editorial Andrés Bello, Santiago de Chile 1979, p. 1205 ( books.google.de [accessed on May 19, 2013]).

- ↑ Alejandro Bertrand (1854–1942): Departamento de Tarapacá. Aspecto jeneral del terreno, su clima i sus producciones . 1st edition. Imprenta de la República, Santiago de Chile August 1879, p. 32 ( memoriachilena.cl [accessed May 19, 2013]).

- ↑ Comité del Salitre [Chile] (ed.): Historias de la pampa salitrera - primer Certamen Literario del Comité del Salitre . Ediciones Colchagua, 1988 ( books.google.de [accessed May 19, 2013]).

- ↑ a b Benjamin Silva: Registros sobre la infancia. Una mirada desde la escuela primaria y sus actores (Tarapacá, Norte de Chile 1880–1922) . In: Revista de Historia Social y de las Mentalidades . El Norte Grande de Chile. tape 13 , no. 2 , 2009, ISSN 0717-5248 ( revistaidea.usach.cl or PDF [accessed on May 19, 2013]). revistaidea.usach.cl ( Memento of the original from August 11, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ A b c Edwin Gonzalo Lopez Pavez: Pozo Almonte. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on December 27, 2009 ; Retrieved May 20, 2013 .

- ↑ Oficina Central de Estadistica en Santiago (Ed.): Sesto Censo Jeneral de la Población de Chile - levantado el 26 de noviembre de 1885 . tape 1 . Imprenta de “La Patria”, Valparaíso 1889 ( memoriachilena.cl [accessed May 19, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c Sergio González Miranda: Del refugio a la globalización. Reflections sobre el aymara chileno y la escuela pública en el siglo XX . In: Educación y Pueblo Aymara . Primera Parte (El Ciclo del Salitre). Universidad Arturo Prat, Instituto de Estudios Andinos "Isluga", Iquique 2000, p. 52 ( unap.cl [ MS Word ; 235 kB ; accessed on May 19, 2013]). unap.cl ( Memento of the original from April 30, 2003 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Enrique Espinoza (1848–): Jeografía descriptiva de la República de Chile arreglada según las últimas divisiones administrativas, las más recientes esploraciones i en conformidad al censo jeneral de la República levantado on 28 de noviembre de 1895 . Imprenta i Encuadernación Barcelona, Santiago de Chile 1897 ( memoriachilena.cl [accessed May 10, 2013]).

- ^ Pastoral diocesana. Parroquia San José de Pozo Almonte. (No longer available online.) Diocesis de Iquique, formerly in the original ; Retrieved May 21, 2013 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Sergio González Miranda: La escuela en la reivindicación obrera salitrera (Tarapacá, 1890–1920) un esquema para su análisis . In: Revista Ciencias Sociales . tape 4 , 1994, ISSN 0718-3631 , p. 19–37 ( revistacienciasociales.cl [PDF; accessed on May 19, 2013]). revistacienciasociales.cl ( Memento of the original from March 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c d Chile. Comisión Central del Censo (ed.): Censo de la República de Chile levantado el 28 de November 1907. Memoria: presentada al Supremo gobierno por la Comisión del Censo . Santiago de Chile 1908, p. 1320 ( memoriachilena.cl [accessed May 19, 2013]).

- ↑ Juan Ricardo Couyoumdjian (1939–): Chile y Gran Bretaña durante la Primera Guerra Mundial y la postguuerra, 1914–1921 . Editoria Andrés Bello, Santiago de Chile 1986, LCCN lc86-222403 , p. 340 ( books.google.de [accessed on May 19, 2013]).

- ↑ Luis Castro: Uns escuela fiscal ausente, una chilenización inexistente: La precaria escolaridad de los Aymaras de Tarapacá durcante el ciclo expansivo del salitre (1880-1920) . In: Cuadernos Interculturales . No. September 3 , 2004, ISSN 0718-0586 .

- ^ A. Lobo, P. Cofré, L. Vieyra: Fiebre de tesoros. Buscan baúles llenos de oro en ex oficina salitrera . In: La Cuarta . El diario popular. September 30, 2005 ( lacuarta.com [accessed May 19, 2013]). lacuarta.com ( Memento of the original from January 12, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Paul Spaudo V .: No descansan en paz . In: La Estrella de Iquique . Iquique August 29, 2005 ( estrellaiquique.cl [accessed May 19, 2013]).

- ↑ Descubren extraña criatura en una salitrera . In: El Mercurio de Antofagasta . No. 34,463 . Empresa Periodística El Norte SA, October 9, 2003 ( mercurioantofagasta.cl [accessed May 19, 2013]).