Laura Wheeler Waring

Laura Wheeler Waring (born May 16, 1887 in Hartford ; died February 3, 1948 in Philadelphia ) was an African-American artist and educator best known for her portraits of prominent African-Americans from the Harlem Renaissance period . She taught art at Cheyney University of Pennsylvania for over 30 years .

Family and childhood

Laura Wheeler was the fourth of six children to Mary (nee Freeman) and the Reverend Robert Foster Wheeler. Her mother's parents were leading members of the American Movement for the Liberation of Slaves , including helping out on the Underground Railroad in Portland, Maine and Brooklyn , New York. Her father was a pastor at the Afro-American Talcott Street Congregational Church , the first Connecticut church to treat all churchgoers equally.

Education and study

In 1906 she graduated from Hartford Public High School in Hartford, Connecticut . Thereafter, it was from the art school Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania was added. In addition to her studies, she taught art and music part-time at the Cheyney Training School for Teachers in Philadelphia , the oldest college for African-Americans in the United States, now known as the Cheyney University of Pennsylvania . There she also worked in the boarding school area in the evenings and on weekends and therefore had little time to devote to her own development as an artist.

When she graduated in 1914, she was a member of the sixth generation of her family to graduate from college. She then received a travel grant , the William E. Cresson Memorial Scholarship of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts , with which she was able to travel to Europe.

Travel to Europe

As an African American, Waring highly valued the social freedoms she experienced in Europe. Her more conventional style, however, was little influenced by modern European art movements. The trips made for a wider awareness in American art circles and brought them in contact with active representatives of the Harlem Renaissance .

She came to Europe three times in her life and each time she stayed in Paris for a long time . With the travel grant, she traveled to Europe for the first time in 1914 for two and a half months. From 1924 to 1925 she spent fifteen months in the company of friends in France, and after their marriage to Walter Waring, the couple stayed in Paris for two and a half months in 1929.

1914

Waring first traveled to Great Britain by ship and went to London , where she visited museums and attractions. Then she drove on to Paris and moved into a room in the bohemian Rive Gauche district . At the Louvre she was particularly interested in the works of the Impressionists such as Edgar Degas , Claude Monet , Édouard Manet , Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot and Paul Cézanne . In her October travelogue for the Pennsylvania Academy , she wrote:

"I thought again and again how little of the beauty of really great pictures is revealed in the reproductions which we see and how freely and with what ease the great masters paint."

Although she did not paint very much at the time, she made notes and drawings. Inspired by her frequent visits to the Jardin du Luxembourg , she later painted the oil painting Le Parc Du Luxembourg (1918).

In Paris, she met other African Americans, including Henry Ossawa Tanner , an artist who was from Pennsylvania but who had settled in Paris in 1895 because of racism in the United States .

Although Waring had planned to travel on to Switzerland, Italy, Germany and the Netherlands, these plans were prevented by the outbreak of the First World War . She left France in mid-August and made a short trip through cities in England and Scotland .

1924 to 1925

In June 1924, Waring traveled directly to France with the Afro-American opera singer Lillian Evanti and the artist Helen Wheatland . Through the friendship with Tanner and his wife, she got to know again cultural workers who were close to the Harlem Renaissance, such as Alain LeRoy Locke and Langston Hughes . Encounters also included activist and historian Rayford Logan , composer Henry Thacker Burleigh , opera singer Roland Hayes , Jamaican poet Claude McKay and Frenchman René Maran , the first black writer to win the Prix Goncourt .

The second stay marked a turning point not only in her artistic style, but also in her professional career. She herself described this time as being exclusively focused on art, as "the only period of undisturbed life as an artist in an environment next to like-minded people who constantly provided stimulation and inspiration." During this time she immersed herself in French culture and way of life. Encouraged by Tanner, she painted many portraits and took painting courses at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière . Instead of soft pastel tones, she now chose a more lively and realistic method. According to art historians, the oil painting Houses at Semur, France (1925) is indicative of this turn .

In addition to painting, Waring wrote and illustrated a short story called Dark Algiers and White with her friend Jessie Redmon Fauset , who played an important role as a publicist in the Harlem Renaissance.

1929

During their belated honeymoon, Waring found inspiration again in the Louvre. For example, she worked on illustrations for the Christmas edition of The Crisis, based on the theme of the Adoration of the Baby Jesus by the Three Wise Men , in which the black Balthasar is highlighted, and also took part in an exhibition in a Paris gallery.

Professional commitment and success as an artist

After her return from Europe in 1914, Waring received orders for illustrations in publications related to the Harlem Renaissance. She contributed many illustrations to the official monthly magazine of the civil rights organization National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), The Crisis , founded in 1910 . She designed several book covers for the youth books of Mary White Ovington , a co-founder of the NAACP, as well as for works by Afro-American authors such as Cordelia Ray and Paul Laurence Dunbar .

From 1920 to 1921 she illustrated for the children's magazine The Brownies' Book , the aim of which was to strengthen the self-confidence of African American children. In line with the philosophy of the New Negro Movement , it was always important for her to present her subjects in a realistic, nuanced and uplifting manner.

After her second stay in Paris, she also provided illustrations for The Crisis and corresponded regularly with WEB Du Bois .

From 1926 her reputation as an artist grew and this earned her recognition and prizes. Her works were selected for the first national exhibition of African American art, organized by the philanthropic Harmon Foundation in 1927 .

Today Waring is best known for her portraits of leading African Americans, including key figures of the Harlem Renaissance, which she painted with Betsy Graves Reyneau in 1943 for the Harmon Foundation. Designed to counter the prevailing stereotypical depictions of African Americans, these images were shown in 32 US cities through 1954. Today a selection of these portraits hangs in the National Portrait Gallery (Washington) .

Some of her works found their way into art collections such as the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC , the Brooklyn Museum, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art .

Private life

On June 23, 1927, Laura Wheeler married Walter Waring, a French and Latin teacher who worked in the Philadelphia state school system. For financial reasons, they had to postpone their honeymoon for two years and then spent over two months together in France. The couple remained childless. Laura Waring's great niece, Madeline Murphy Raab, is an art collector and privately owned some of Waring's works.

death

Wheeler-Waring died on February 3, 1948 at home in Philadelphia after a lengthy illness. Just a year later , an exhibition was dedicated to her in the art gallery of Howard University in Washington, DC, the most famous American university for African-Americans.

Important works

- Anna Washington Derry (1927)

- A Dance in the Round (1935)

- Nude in Relief (1937)

- Heirlooms (watercolor) (1916)

- Portrait of Alma Thomas (1945)

Selected portraits

|

|

|

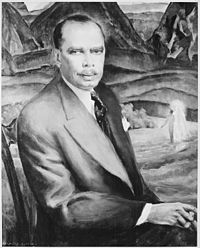

| WEB you Bois | James Weldon Johnson | Anna Washington Derry |

literature

- Michael Rosenfeld: African American art: 200 years: 40 distinctive voices reveal the breadth of nineteenth and twentieth century art . Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York, NY 2008, ISBN 9781930416437 .

- Lisa E. Farrington: Creating their own image: the history of African-American women artists . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2011, ISBN 0199767602 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Arna Alexander Bontemps, Jacqueline Fonvielle-Bontemps: African-American Women Artists: An Historical Perspective . In: Sage: A Scholarly Journal on Black Women . tape 4 , no. 1 , 1987, pp. 17-24 ( google.com ).

- ↑ Laura Wheeler Waring. In: Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame. Retrieved June 15, 2019 .

- ^ Abyssinian Congregational Church. Congregational Library & Archives, accessed May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Sara Jane Cedrone: Faith Congregational Church: 185 Years. Connecticut Explored, March 31, 2016, accessed May 25, 2019 .

- ↑ Laura Wheeler Waring. Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame, accessed May 5, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Theresa Leininger-Miller: A Constant Stimulus and Inspiration . Laura Wheeler Waring in Paris in the 1910s and 1920s. In: Source: Notes in the History of Art . tape 24 , no. 4 , 2005, p. 13-23 , JSTOR : 23207946 .

- ↑ Amy Helene Kirschke: Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance ( en ). University Press of Mississippi, Aug 4, 2014, ISBN 9781626742079 , 77.

- ^ A b James A. Porter: The Work of Laura Waring . In: James A. Porter and James Herring (Eds.): In Memoriam. Laura Wheeler Waring 1887-1948: An Exhibition of Paintings . Howard University Art Gallery, Washington, DC 1949, p. unmarked Bl .

- ↑ John Welch: Article # 2 (Laura Wheeler Waring). In: International Review of African American Art. Hampton University, accessed May 7, 2019 .

- ^ Art and Culture: Exploring Freedom / Laura Wheeler Waring , African American World, PBS-WNET

- ↑ a b Lacinda Mennenga: Laura Wheeler Waring (1887-1948). Black Past.org, January 28, 2014, accessed May 25, 2019 .

- ↑ Amanda Cleary Eastep: Creating a Life's Work in African-American Art. In: Illinois Tech Magazine. Illinois Institute of Technology, 2016, accessed May 7, 2019 .

- ↑ Laura Wheeler Waring. American artist. Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed May 25, 2019 .

- ↑ Anna Washington Derry by Laura Wheeler Waring / American Art .

- ^ Alma Thomas, Fort Wayne Museum of Art: Alma W. Thomas: A Retrospective of the Paintings ( en ). Pomegranate, 1998, ISBN 9780764906862 , p. 22.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wheeler Waring, Laura |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wheeler, Laura (maiden name); Waring, Laura (married name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American painter and teacher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 16, 1887 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hartford, Connecticut |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 3, 1948 |

| Place of death | Philadelphia , Pennsylvania |