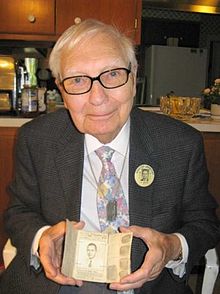

Lee Davenport

Lee L. Davenport (born December 31, 1915 in Schenectady , New York State , † September 30, 2011 in Greenwich , Connecticut ) was an American physicist. During the Second World War he was a member of the MIT Radiation Laboratory , where he was responsible for the development and use of the AN / SCR-584 radar system.

Lee Losee Davenport was born on December 31, 1915 in Schenectady, New York State ( USA ). His father Harry was a math teacher in a secondary school . Davenport showed an early interest in electrical engineering and built electric motors out of paper clips and copper wire.

In 1937 Davenport received his bachelor's degree from Union College , a private college in Schenectady. Three years later he received a masters degree in physics from the University of Pittsburgh . In a postgraduate course , he worked there on his doctoral thesis at the age of 25. During this time he was appointed to the Radiation Laboratory of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he was responsible for developing the radar program for the AN / SCR-584, a precise automatic fire control radar that uses about 85 percent of V1 attacks were shot down on London.

In his capacity as a research fellow at the Radiation Laboratory, Davenport worked closely with General Electric , Westinghouse and Bell Laboratories . By the end of the Second World War, more than 3000 radars of this type had been delivered.

The AN / SCR-584 was technically excellent, but it required skilled operators. Davenport recognized this as a possible problem on a trip to England because some of the gun operators did not know how the radar system worked. In one of the positions, the American soldiers were still reading the operating manual while a V1 was flying over. In the 1996 book The Invention That Changed the World: How a Small Group of Radar Pioneers Won the Second World War and Launched a Technological Revolution by Robert Buderi, he published an interview with Davenport in which he recalled that during this stay in England flew seven or eight of these V1s past the position without the crew being able to fire a single shot.

Davenport was back in England two months before landing in Normandy to check the thirty-nine trailers with the AN / SCR-584 that were destined to be brought ashore in Normandy to control the anti-aircraft fire. Davenport was one of the few people who knew the date of the planned invasion.

Shortly after the invasion began, Davenport was a few miles behind the front to test the capabilities of the AN / SCR-584. He was wearing papers that identified him as captain of the communications troops if he were to be captured. The AN / SCR-584 was also used in the Pacific theater of war, for example to retake the Philippines.

After the war, Davenport completed his PhD in 1946 at the University of Pittsburgh. The content of the dissertation was the construction of a radar-guided missile , which was practically the first automatic guided missile . From 1946 to 1950 he worked at Harvard University , where he directed the construction of what was then the second largest (92-inch) cyclotron and taught physics at Radcliffe College .

After Harvard, Davenport became chief engineer for the development of a guided bomb system for the B-47 bomber at PerkinElmer . This guided bomb system included an analog computer . He became Managing Director of Perkin-Elmer, then Vice President, Director and Chief Engineer of Sylvania Electric Products . In 1962 he was named President of General Telephone & Electric Corporation .

Davenport survived a plane crash on July 2, 1963. He then recommended, during a United States congressional hearing, that seat belts be installed in the aircraft to increase the safety of passengers.

Davenport was a member of the American Physical Society and was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 1973 for "Contributions to the Development of Radar, Infrared Analytical Instrumentation and Guidance in the Development of Communication Technology" .

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c d e f g Richard Goldstein, "Lee Davenport Dies at 95; Developed Battlefront Radar," The New York Times, September 30, 2011 at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/01/science /01davenport.html

- ^ A b c Anne W. Semmes, "Lee Davenport, researcher at the Radiation Laboratory during World War II, dies at 95," MIT Press Release, October 4, 2011 at http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2011 /obit-davenport.html

- ↑ a b c d e f g Frank MacEachern and Anne Semmes, "Lee Davenport, developer of anti-aircraft radar, dies at 95," Greenwich Time, October 4, 2011 at http://www.greenwichtime.com/news/ article / Lee-Davenport-developer-of-anti-aircraft-radar-2201112.php

- ↑ Robert Buderi, "The Invention That Changed the World: How a Small Group of Radar Pioneers won the Second World War and Launched a Technological Revolution," Touchstone, March 23, 1998, 576 pages (via Amazon) at http: // www .amazon.com / INVENTION-THAT-CHANGED-WORLD-PIONEERS / dp / 0684835290 /

- ↑ Dr. Lee L. Davenport, National Academy of Engineering Web Site at http://www.nae.edu/MembersSection/Directory20412/29514.aspx

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Davenport, Lee |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Davenport, Lee L. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American physicist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 31, 1915 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Schenectady , New York State |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 30, 2011 |

| Place of death | Greenwich , Connecticut State |