Teaching of Amenemhet

The doctrine of Amenemhet is an ancient Egyptian literary work that is based on the formal model of the doctrine of life and private autobiography . The central passage depicts an assassination attempt on the king ( pharaoh ) Amenemhet I. Although the text has only come down from manuscripts of the New Kingdom , its origin undisputedly dates to the 12th dynasty of the Middle Kingdom . Either it was commissioned by Amenemhet I himself to justify a co-reign of his son Sesostris I or it was written down at the instigation of Sesostris I to justify his successor.

Lore

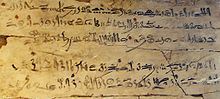

The teaching of Amenemhet has only come down to us from copies from the New Kingdom. With three quarters of the entire text, the Millingen papyrus was the most complete known text witness. This comes from the 18th dynasty , but has disappeared since the middle of the 19th century and there is only one hand copy of it. It is complemented by the Ramesside papyrus Sallier II. Other text witnesses are three papyrus fragments, a leather scroll, three wooden panels and numerous ostraca .

In his most recent edition from 2006, Faried Adrom noticed that since the groundbreaking edition by Wolfgang Helck in 1969, with the 68 known text witnesses at the time, the number of documents has almost quadrupled. In particular, there are still many unpublished ostraka from Deir el-Medina .

The heavily corrupted Ramessid manuscripts often cause difficulties in understanding the text. They are largely structured in the same way: red bullets separate 87 verses , red line beginnings divide the text into 15 sections .

content

The text begins with the usual introductory scheme of the doctrines of life, which contains the generic name, addressee and circumstances: The late Amenemhet I addresses his son and heir to the throne Sesostris I in his teaching. He urges him to listen to his advice since he is now King of Egypt is:

- You will be king of the land!

You will rule the banks!

You will increase the good!

The following section with a chain of requests and prohibitions for correct behavior corresponds most closely to the classical teachings. Amenemhet calls on Sesostris to be suspicious of the environment. He should not trust anyone, because that would not lead to anything. Especially at night, he should only rely on himself - and not on his bodyguards.

After that, the style of teaching is abandoned and in the following three sections the late king boasts of his good deeds in the style of a private autobiography (ideal biography). In particular, he emphasizes his benefits towards the socially disadvantaged. At the same time, however, he complained that all good deeds were useless, because nobody thanked him with loyalty.

Now he turns to all of his descendants. You should prepare a funeral and a keepsake for him like no one has ever heard.

The king vividly describes the initial situation of the assassination attempt, but many details of the fight and the outcome are left in the dark.

- It was after supper and night had come.

I gave myself an hour of refreshment

by lying on my bed because I was tired

and my heart began to indulge in my sleep.

The weapons were turned against me for protection

while I acted like a snake in the desert.

- I woke up to the fight by being with myself immediately

and found it to be a scuffle between the guards.

I hurried, weapons in my hand,

and so I drove the cowards back into (their) lair.

But there is no one who can fight alone,

and a successful deed cannot be achieved without helpers.

Amenemhet also reports that the assassination attempt took place when he was without Sesostris I, which is reminiscent of the story of Sinuhe , in which it is described that Sesostris I was on a campaign in Libya when this took place. He worries about the failure to introduce his son to government in a timely manner:

- You see, the attack happened when I was without you,

without the court having heard that I was bequeathing to you,

without my sitting (on the throne) with you.

Oh, if I could take care of your matter now,

because I had not prepared or considered it.

My heart did not notice the servants' unreliability.

Apparently, the king fell victim to a harem conspiracy that he could not have foreseen, which had never happened before and is an incredible act:

- Had women ever raised troops?

Are rebels raised in the palace?

In the following, again in the style of an ideal biography, the good deeds that Amenemhet performed are listed. This is how his acts as a war hero and peacemaker are summed up. He fulfilled the commandments of the Maat and the Nile god Hapi showed himself to be praised by regularly sending him a regular flood of the Nile and the grain god Nepri prepared him rich harvests.

The king cites the slanderous talk in the street , by which the stupid is only too easily influenced, as an explanation for the fact that the monstrous deed could still come about.

In the following sentences he expresses the unity of the union with his son, says goodbye to him and appoints him posthumously as the last official act as his successor:

- The white crown is placed on the offspring of God,

and (all) things are in the right place, as I started for you.

The conclusion returns to the style of the teaching, but is very poorly preserved. It contains actions that Amenemhet calls upon the new king, the last of which concerns the protection of the wise man.

Authorship

In a later tradition one finds a possible reference to Cheti as an author , to whom the teaching of Cheti and the Nile hymn are ascribed:

- Resurrection and sight of the sun for the scribe Cheti, and a dead sacrifice made of bread and beer before Wennofer ( Osiris ), libations , wine and linen for his spirit and his pupils, for the effective with the exquisite sayings! I will call his name forever. It is he who made a book with the teaching of King Sehetibre after he fell asleep, after he had united with the necropolis and had come under the lords of the necropolis.

It is noteworthy that the New Kingdom teaching was viewed as the creation of a famous "sage" rather than that of a fictional writer. The numerous student manuscripts also indicate the appreciation this was shown.

Co-regency of Amenemhet I with Sesostris I

According to some Egyptologists , Amenemhet I installed his son Sesostris I as co-regent in his 20th year of reign and both ruled together on the Egyptian throne for ten years. The question of coregences in ancient Egypt in general, and especially that of Amenemhet I with Sesostris I, is one of the most controversial questions in Egyptology. According to the theology and “royal ideology” of the ancient Egyptians, the king is a singular, divine being and can therefore only be presented as the sole ruler. He reigns as the embodiment of Horus on earth and, after his death, merges with Osiris , the ruler of the underworld. With this concept it is hardly compatible that two Horus falcons suddenly rule. On the other hand, for pragmatic reasons, co-membership certainly had many advantages:

- A change of throne, and thus a change of power, in Egypt, as in other oriental monarchies , must have been staged very often through harem intrigues , murders and overturns, undoubtedly much more often than the few times our sources say or suggest such things. [...] In connection with the change of throne, violent action was more the rule than the exception. The early coronation of the designated successor, while the old king was still alive, offered a certain degree of security against these dangers: at the death of the old ruler, if you wanted to make someone else than the legitimate heir king, you would have had to eliminate an already crowned monarch.

As evidence for or against a coregence, some passages of the text of the teaching of Amenemhet have been brought into the field and the existence of such is crucial for the interpretation of the teaching.

Interpretation of the attack

The teaching does not explicitly say whether the attack on Amenemhet I was really successful. This question is closely related to the question of Amenemhet I's co-reign with Sesostris I and central to the history of the 12th Dynasty, for the interpretation of this work and for the historical background of the story of Sinuhe: If the king was actually murdered , the beginning of this story, where the death of Amenemhet I and the somehow related flight of Sinuhes is reported, refers to the same event .

According to one opinion, Amenemhet did not die by an assassination attempt in his 30th year of reign, but escaped such an attack about 10 years before his (natural) death and as a consequence established the office of co-ruler for his son Sesostris. Accordingly, Amenemhet commissioned the teaching and it describes a "what-if" situation to justify the position of co-ruler.

According to another view, the story of Sinuhe and the teaching of Amenemhet both portray the historical circumstances of Amenemhet's death. The doctrine was commissioned by Sesostris after Amenemhet's death to legitimize his succession.

literature

Editions

- Aksel Volten: Two Ancient Egyptian Political Writings. The lesson for King Merikarê (Pap. Carlsberg VI) and the lesson of King Amenemhet. In: Analecta Aegyptiaca (AnAe) No. 4, 1945, pp. 3-103.

- Wolfgang Helck : The text of the "Doctrine of Amenemhet I for his son". In: Small Egyptian Texts. (KÄT) No. 1, 1969.

- Faried Adrom: The teaching of Amenemhet (= Bibliotheca Aegyptiaca . (BAe) Bd. XIX). 2006.

Translations

- Wolfgang Kosack : Berlin booklets on Egyptian literature 1 - 12. Part I. 1 - 6 / Part II. 7 - 12 (2 volumes). Parallel texts in hieroglyphics with introductions and translation. Book 9: The teaching of King Amenemhet I to his son. Christoph Brunner, Basel 2015, ISBN 978-3-906206-11-0 .

- Miriam Lichtheim: Ancient Egyptian Literature. Vol. I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms. 1973, pp. 135-139.

- Hellmut Brunner: Ancient Egyptian wisdom. Lessons for Life. The library of the old world. 1988, pp. 169-177.

- Richard B. Parkinson: The Tale of Sinuhe and other Ancient Egyptian Poems 1940-1640 BC (= Oxford World's Classics ). Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 1997, ISBN 0-19-814963-8 , pp. 203-211.

- Edward Wente, William Kelley Simpson (eds.), Vincent A. Tobin, Robert K. Ritner (both translators): The Literature of Ancient Egypt. an Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry. 2003, pp. 166-171.

General literature

- Elke Blumenthal: Teaching Amenemhets I. In: Wolfgang Helck (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Ägyptologie. (LA) Vol. 3, Col. 968-971.

- Günter Burkard, Heinz J. Thissen: Introduction to the ancient Egyptian literary history I, Old and Middle Kingdom. 3rd ed., 2008, pp. 107-114.

- Gabriele Höber-Kamel: Didactic poetry of the Middle Kingdom - The teaching of Amen-em-hat for his son Sesostris. In: Kemet. No. 3, 2000.

- Antonio Loprieno (Ed.): Ancient Egyptian Literature. History and Forms. 1996

- Richard B. Parkinson: Poetry and Culture in Middle Kingdom Egypt. A dark side to perfection. 2002, pp. 241-248.

Individual contributions

- Elke Blumenthal: The teaching of King Amenemhet. Part I and II, In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Archeology. 111, 1984, pp. 85-107 and 112, 1985, pp. 104-115.

- A. de Buck: La composition littéraire des enseignements d'Amenemhat. In: Le Muséo n 59, 1946, pp. 183-200.

- Günter Burkard: "When God appeared he spoke." The teaching of Amenemhet as a posthumous legacy. In: Jan Assmann, Elke Blumenthal (ed.): Literature and politics in Pharaonic and Ptolemaic Egypt. (= Bibliothéque d'étude. Vol. 127). 1999, pp. 153-173 ( digitized version ).

- Günter Burkard: "The king is dead." The teaching of the Egyptian king Amenemhet I. In: Martin Hose (Ed.): Large texts of ancient cultures. Literary journey from Giza to Rome. 2004, pp. 15-36 ( digitized version ).

- Andreas Dorn: Further fragments on Ostrakon Qurna TT 85/60 with the beginning of the teaching of Amenemhet I. In: Göttinger Miszellen . 206, 2005, pp. 25-28.

- John Foster: The Conclusion to the Testament of Amenemmes, King of Egypt. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology. 67, 1981, pp. 36-47.

- Karl Jansen-Winkeln: The assassination attempt on Amenemhet I and the first Egyptian co-regency. (= Studies on Ancient Egyptian Culture. Vol. 18) 1991, pp. 241-264.

- Georges Posener: Littérature et politique dans l'Égypte de la XIIe dynastie. 1956, pp. 61-86.

Web links

- The Teaching of King Amenemhat I English translation, background information, ostraca of the Petrie Museum

- Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae transcription and German translation

- British Museum: A poem on papyrus description of the Sallier II papyrus

Individual evidence

- ↑ Faried Adrom: The teaching of Amenemhet. 2006, SV

- ↑ G. Burkard, HJ Thissen: Literaturgeschichte I. S. 109; for a list of all text witnesses see publication by Wolfgang Helck: The text of the "Amenemhet I teachings for his son". Pp. 1-6.

- ↑ Amenemhet is clearly identified as the deceased by the designation m3ˁ ḫrw (= the justified ).

- ^ Teaching of Amenemhet I. Id-e, translation: G. Burkard, HJ Thissen: Literaturgeschichte I. S. 114

- ^ Doctrine of Amenemhet VI-VII. Translation: Elke Blumenthal: Teacher of King Amenemhet. In: ZÄS 111, 1984 , p. 94.

- ↑ Doctrine of Amenemhet VIII. Translation: Blumenthal: Doctrine of King Amenemhet. In: ZÄS 111, 1984 , p. 94.

- ↑ Doctrine of Amenemhet IX. Translation: G. Burkard, HJ Thissen: Literary History I. S. 112

- ↑ Doctrine of Amenemhet XV. Translation: Blumenthal: Doctrine of King Amenemhet. In: ZÄS 111, 1984 , p. 95.

- ^ Table of contents after submission of the table of contents and translation by E. Blumenthal: Doctrine of the King Amenemhet. In: ZÄS 111, 1984, p. 86 ff; G. Burkard, HJ Thissen: History of Literature I. S. 107 ff .; Gabriele Höber-Kamel, in: Kemet 3/2000 , p. 36 ff.

- ↑ Papyrus Chester Beatty IV, vso. VI, 11 ff., Translation: G. Burkard, HJ Thissen: Literaturgeschichte I. S. 109.

- ↑ E. Blumenthal: Doctrine of Amenemhet. In: LÄ III , Sp. 970 f.

- ↑ Michael Höveler-Müller: In the beginning there was Egypt. 2005, p. 152.

- ^ Karl Jansen-Winkeln: On the coregences of the 12th dynasty. In: SAK 24 , 1997.

- ↑ Jansen-Winkeln: The assassination attempt on Amenemhet I and the first Egyptian coregenthood. In: SAK 18 , p. 241.

- ↑ Michael Höveler-Müller: In the beginning there was Egypt. 2005, p. 153.

- ↑ G. Burkard, HJ Thissen: Literaturgeschichte I. S. 113