Mother's song Courage

The Song of Mother Courage , also known as Mother Courage's business song , is a song sung by the title character in the drama Mother Courage and Her Children by Bertolt Brecht . The stanzas of the song are spread over several scenes of the piece and characterize the protagonist of the piece, the mother Courage. It is their performance song in the first picture and at the same time marks the end of the plot in the last picture, thus creating a framework for the drama.

Bertolt Brecht probably wrote the text of the song at the end of 1939 while in exile in Sweden; He made some changes and additions for the performance of the drama. The music that is binding today comes from Paul Dessau , for the world premiere of Mother Courage in 1941 in Zurich, Paul Burkhard has already put in a setting. However, the melody used by both composers has a longer history. Brecht has already backed it up with his ballad of the pirates , which he published in 1927 in the Hauspostille , including song notes in a sheet music appendix. However, he did not compose it himself, but adopted it from a French chanson : L'Étendard de la Pitiéas he himself states.

The mother's song Courage was very popular, especially in the post-war period. Brecht was not entirely happy with this popularity, however, because he said this was the case for the wrong reasons: the stage character Courage was perceived too positively. Paul Dessau used the melody of the song, which was inextricably linked to Brecht after the success of Mother Courage and her children , one more time, namely as the cantus firmus in his instrumental work In memoriam Bertolt Brecht .

History of origin

Brecht probably wrote Mother Courage's song in September / October 1939 in Swedish exile on Lidingö , according to his close colleague Margarete Steffin . On the occasion of the first Danish performance of the drama, he stated in the program booklet that the play had been written in his home in Svendborg , Denmark, before the start of the Second World War ; however, there is no confirmatory evidence for this.

The song is already mentioned in an early overview of scenes from the development phase of the piece, which cannot be dated exactly. For the first scene, Brecht noted the beginning of the later refrain (“Spring is coming”) and the biblical quote “Let the dead bury the dead” (cf. Mt 8.22 EU , Lk 9.60 EU ), which refers to the progress of the Refrains refers ("The snow is melting away / The dead rest / And what has not yet died / This is getting on your socks now"). This he accompanied with the word "pirates", which on its own, in the 1927 Hauspostille published Ballad of the pirates points.

Origins of the melody: pirate ballad and pity standard

According to Hanns Otto Münsterer's testimony, the ballad of the pirates must have been written by 1918 at the latest. Münsterer, a childhood friend of Brecht, remembers hearing the work this year, performed in two voices by Bertolt Brecht and his brother Walter Brecht and accompanied by both of them on guitar. It was first published in print in the Berlin Börsen-Courier on April 1, 1923, but without any information about the music. Finally it found its way into the pocket postil and the house postil (1926 and 1927), and this time also with music: the notes attached to these volumes of poetry contained two slightly different versions of the melody.

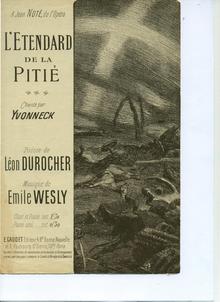

In the instructions for using the individual lessons , his introduction to the house postil , Brecht stated that the musical elaboration did not come from himself. He wrote: “The melody is that of L'Etendard de la Pitié.” This source, which has remained unknown for a long time, was only found in 2012: it is a chanson printed in Paris in 1905, the title correctly reproduced by Brecht can be understood translate as "The Standard of Compassion ". The melody comes from the journalist and composer Émile Wesly , who was born in Maastricht and lives in Brussels, and the text is from the French writer and Breton bard Léon Durocher . The piece is a hymn to the humanitarian achievements of the Red Cross on the battlefield. The Breton bard Yvonneck was the first to interpret it. There are at least two contemporary recordings on shellac ; The song is sung there by the Belgian opera singer Jean Noté (recorded in 1905 by Odéon Paris) and by the French chansonnier Marcelly (recorded in 1908 by Pathé ).

How Brecht came across this melody is unknown. In any case, he took it over from the pirates for the ballad , albeit with a few changes, especially in the later part of the verse. Elements of the melody can also be found in other early songs by Brecht, in particular the characteristic opening motif, namely in the first setting of the Barbara song (for which Brecht and Franz Servatius Bruinier were jointly responsible) and in the song of the roses from the Schipkapass (one melody for one von Brecht is available). Wesly's melody was eventually taken over, with certain changes, in the setting of Mother Courage's song.

Text history

Brecht revised the lyrics several times in the course of the piece's creation. There are roughly three versions: a typescript of the drama, written in 1939; the first stage manuscript that was written for the world premiere in Zurich in 1941; and finally the print in Brecht's series of attempts , which again exists in two slightly different versions, written before and after the Berlin premiere, which Brecht himself directed. In addition, there are two separate publications of the song in collections of the Courage songs in 1948 and 1949, which in turn reflect slightly different editing states.

The first stanza of the song has hardly changed, with one exception: The salutation, which was originally in the singular (“Herr Hauptmann, let the drum rest”), was probably put in the plural for technical reasons (“Ihr Hauptleut”). In the second stanza, Brecht replaced a few verses after the first typescript in order to give them a sharper outline; The same applies to the final stanza.

The most drastic change, however, was the insertion of a new half-stanza before verse 3. It does not fit into the stanza model that is otherwise consistently observed, because it is to be sung to the melody of verses 5 to 8, so it starts in the middle of the song, so to speak. It is missing in the separate prints of the song; it was apparently only intended for the performance of the piece, but it was intended to be binding for these. In this case, Brecht himself justified the addition: The half-strophe in the 7th picture should counteract an overly positive assessment of the Courage figure. Essential for this are the lines: "War is nothing but business / And instead of cheese, it's lead."

History of the settings

First, Brecht approached the Finnish composer Simon Parmet about a setting of his drama. He attached great importance to the fact that Parmet used the melody of L'Etendard de la Pitié for the setting of the song of the mother Courage . Parmet reported on this later in 1957 in the Swiss music newspaper :

- “He [Brecht] had fallen so much in love with an old French soldier's style that he absolutely persisted in demanding that it go into the new work as a kind of leitmotif song. He sang the tune to me repeatedly, whistled and drummed it, and each time he became more enthusiastic about its hulking beauty. "

Parmet's setting has never been performed, the score is believed to have been lost.

Paul Burkhard wrote the incidental music for the Zurich premiere of the drama in 1941. For the song of his mother, Courage , he was guided by notes that he apparently received indirectly from Brecht. It is not clear whether it was Parmet's missing setting or a compilation of various melody models made by Brecht himself. In any case, Burkhard took over the melody of the pirate ballad for the stanzas of the song, but composed a new, considerably different melody for the refrain. Among other things, he changed the key ratio of verse and chorus. He also wrote out the instrument parts for the stage music.

In 1943 Brecht met Paul Dessau in American exile and in 1946 performed songs from Mother Courage for him. For the song of Mother Courage, he used the published melody of the pirate ballad. Dessau was irritated by Brecht's “polite” hint that he “wanted to have used” the Dessau melody by L'Étendard de la Pitié for the song of Mother Courage - “this kind of plagiarism” was completely alien to him at the time. However, he followed Brecht's wishes and set the entire piece to music "in close collaboration with Brecht".

In August 1946, Dessau completed a first version of the drama, the so-called “American version”, which comprised a total of twelve musical numbers and was dedicated to Helene Weigel . In 1948 he began to revise this composition for the Berlin premiere of Mother Courage , which also took into account the text changes made by Brecht in the meantime.

Dessau did not change anything in the pitch order of Brecht's original in the song of the mother Courage , but did intervene strongly in meter and rhythm . He took the play to start (the melody now sat downbeat one) and put the three-quarter time with irregularly scattered two quarter cycles. In consultation with Brecht, he also prescribed a prepared piano for the instrumentation, the so-called bug piano or guitar piano with tacks on the felt hammers.

Brecht's conception of music and songs

Song form: music as part of the work

When conceiving and writing his texts, Brecht often had the lecture in mind. Above all, poems and songs were often conceived from a musical structure. This also applies to the mother Courage . The importance of the songs and their performance in Brecht's eyes can already be seen in the production history. An overview of the scenes from an early stage of the development history hardly contains any details of the plot, but does contain information about the songs that correspond to the individual scenes. In the first scene there are individual snippets of text from the later song of the mother Courage and the word "Seeräuber" - a reference to Brecht's own ballad about the pirates , written in the early 1920s , which had long been set to music in the notes attached to the house postil with the note: “The melody is that of L'Etendard de la Pitié .” The song by Mother Courage was therefore intended from the start as a counterfactor to this melody. Accordingly, it uses the meter of the pirate ballad , an iambic four-lifter with a caesura after the second foot of the verse . Brecht often used such subdivided verse forms that he had already found (for example in the memory of Marie A. ); they gave him the opportunity to use the caesura as a turning point or to play it over freely.

Over the entire history of the creation of the piece, Brecht gave his composers considerable freedom, but insisted on certain melodic, rhythmic or general stylistic elements. This is especially true of the song by Mother Courage , the melody of which he strongly recommended to all composers involved. It was all about the character of recognizability.

Structuring through the songs

Since Brecht wants to do without the tension curve of the classic drama and the individual scenes do not follow a strict structure, Brecht uses other means to structure the drama. The repetition of the song of courage from the beginning at the end of the piece forms a kind of framework, which in the Berlin production supported the repetition of the open horizon of the set. The two pictures show a clear contrast. If the first picture shows the family united on the intact wagon, the impoverished courage in the end pulls the empty wagon alone to war.

Analysis of the song

The song of the mother Courage serves as a framework for the entire piece and characterizes the protagonist and her development. It has a stanza - refrain structure, the refrain is never changed.

The first two stanzas of the song answer the sergeant's question: “Who are you?” Mother Courage first answers “business people” and then begins to sing. She addresses the officers directly and offers them their goods.

In the original of the song, Brecht's ballad from the pirates from the 1920s, the melody always begins with an upbeat , initially with the signal-like falling minor triad in eighth notes. While the stanzas are obviously based on D minor as the key, the refrain changes to the parallel major key of F major. This change also corresponds to a change of mood and tempo for the pirates : from the quick stanza with the dangers of pirate life to a much broader, emphatic hymn to heaven, wind and sea ("O heaven, radiant azure"). It ends in a four-fold repetition of the note, which remains 'above', on the D, and is only brought back to the root note in the following stanza. Brecht's childhood friend Hanns Otto Münsterer commented that the chorus sang the “Song of Songs for the instinctual, unrestrained life of the anti-social”.

This dichotomy is introduced into the song of Mother Courage by adopting the rhythm and melody of the pirate ballad . Here, too, the stanzas provide the gloomy backdrop and partly also the progression of the plot, the refrain celebrates anarchic life again, unconcerned about the threat of death, as was already the case with the pirates . The style level is of course much lower: Here it is the unbearable life that, in the spring, if it has “not yet died”, “picks up” again.

The use of the Hauspostille material reflects Brecht's re-evaluation and re-appropriation of his hymns from the early 1920s. In 1940 he noted in his work journal on the Hauspostille poems: “Here literature reaches that degree of dehumanism that Marx sees in the proletariat, and at the same time the hopelessness that inspires it. Most of the poems are about doom, and the poetry follows declining society to the ground. the beauty is established on wrecks, the last fragments become delicate. the sublime wallows in the dust, the senselessness is welcomed as a liberator. the poet no longer even shows solidarity with himself. ”Brecht does not abandon his anti-social figures, but he changes their assessment and transfers them to a new context. Matthias Tischer comments on what this transmission could have made for the audience: “The verses of the song, reinforced by the memorability of the melody, must reflect many that had just emerged from bunkers and cellars and, bit by bit, the extent of the devastation of war and Fascism were brought to mind, have become sayings and leitmotifs in times of total loss of meaning. "

Dessau has adopted the melody practically unchanged, especially in the pitch sequence, but has set new accents through metrics, rhythm, harmony and instrumentation. Instead of the up-bar eighth note, his composition begins with full-bar quarters, underlaid with continuous staccato quarters from the accompanying guitar piano with its metallic timbre. The "graceful folds" of the template are eliminated, it gets a certain "clunkiness", a pounding, march-like appearance. Of course, this march has something dubious, “clumsy rumbling” about it due to the recurring, irregular insertions of two-quarter bars and the noticeable shortening and widening of the metric cells. It is not easy to march after this march. The chorus is dominated by a composed slowing down of the melody by hemioli , i. H. the continued three-quarter time of the accompaniment is actually opposed to a three-half time in the melody. In the finale, the tempo is broadened again until whole notes form the beat; it gives the impression of stretching, in line with the text (“the war, it lasts a hundred years”).

In addition, there is an idiosyncratic rhythm: the long note values in the stanzas are on unstressed final syllables (rest, better), the result is a declamation like in bänkelsang with "wrong", senseless emphasis on the dispatch, as Brecht does with his own Also used song recitals in the 1920s.

The harmony is peculiarly obscure, as Fritz Hennenberg noted. The minor triad of the first melody phrase in the bass foundation is by no means subject to the actually required tonic in E minor, but rather a subdominant chord in A minor with the root note A, which rubs against the melody tones. This chord is repeated incessantly for 13 bars, while different harmonic functions alternate in the treble of the accompaniment (tonic, subdominant parallel, dominant ). This simultaneous harmonic function creates the impression of a “wrong” accompaniment. The harmonic functions actually required of it are withheld from the melody. The resulting “multiple thirds” are a characteristic of Dessau's song compositions. This means, too, contributes to the impression of the infinity of the march; there is no longer a regular course of tension and relaxation.

Dessau also built trumpet signals into the movement, which stand out because of their "penetratingly constant". In the last chorus there are two piccolo flutes that play falling small seconds - “ chains of sighs ”, a motif from the baroque tonal speech that expresses emblematic pain (for example in Johann Sebastian Bach ). Of course, they are stripped of their baroque beauty by being led at a seventh interval, which results in violent friction (Tischer speaks of the “screeching of the piccolo flutes”). The instrumentation has a very pictorial character: the never-ending march accompanied in pounding quarters, albeit stumbling, the trumpet signals as commands, the flutes as Landsknecht instruments.

Matthias Tischer interprets these characteristics as “symbols and emblems of the simultaneous questionability and immutability of the war”, and Gerd Rienäcker specifies that one hears “the infinite marching step, in which the gruesome words of the war, which still lasts for the 'hundred years' to find their symbolic confirmation ”.

Other uses of the melody

Immediately after completing the “American version” in 1946, Paul Dessau began to work on converting the incidental music into a purely instrumental piece in the form of a suite . On May 8, 1948, he completed the score for the suite. It was intended for 15 instruments: two flutes, three horns, three trumpets, three trombones, harmonica, prepared piano and timpani. The autograph has survived but has not been published. The first movement is titled March Fantasy and uses the song of Mother Courage . In 1956/1957, after Brecht's death, the piece was included in the second movement of Dessau's composition In memoriam Bertolt Brecht . This sentence is accompanied by a courage quote The war shall be cursed! named; the melody of Mother Courage's song here forms a kind of cantus firmus . The counterpoints on this theme are also composed of parts of the incidental music.

Sources

Simon Parmet's setting is lost. Parmet himself claims that he destroyed everything but one piece. His estate cannot be found, and the documents are no longer available from the Kurt Reiss theater publisher or from the participants in the premiere.

Paul Burkhard's version has not been published. However, there is a copy (piano reduction), presumably made by his wife, which is accessible in the Paul Burkhard Archive and various libraries and is also cited in the literature in excerpts. The autograph has not yet been found; the Paul Burkhard Archive, however, is still waiting for systematic processing.

Paul Dessau's American version from 1946 is only available as a manuscript. In 1949 he published two piano reductions of songs from Mother Courage ( seven songs for "Mother Courage and Her Children" and nine songs for "Mother Courage and Her Children" ), which represent two different stages of editing Mother Courage's song . A complete score of the stage music has existed since 1957, published by Henschel Verlag Kunst und Gesellschaft, but is only available as loan material for the stage and is not accessible in libraries.

literature

swell

Text output

- Bertolt Brecht: Mother Courage and her children. A chronicle from the Thirty Years War . In: Attempts , Issue 9 [2. Edition] (attempts 20–21), Suhrkamp, Berlin 1950, pp. 3–80 (20th attempt, modified text version).

- Mother Courage and her children . Stage version by the Berliner Ensemble, Henschel, Berlin 1968.

- Bertolt Brecht: Mother Courage and her children . In: Works. Large annotated Berlin and Frankfurt editions (Volume 6): Pieces 6 , Suhrkamp, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 978-3-518-40066-1 , pp. 7–86.

grades

- Brecht / Dessau: 7 songs to Mother Courage and her children . Verlag "Lied der Zeit", Berlin 1949.

- Brecht / Dessau: 9 songs. Mother Courage and her children . Thüringer Volksverlag, Weimar 1949.

- Fritz Hennenberg (ed.): Brecht song book . Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-518-37716-7 .

Others

- Bertolt Brecht: Courage model 1949 . Henschelverlag, Berlin (GDR) 1961.

Secondary literature

- Gerd Eversberg : Bertolt Brecht - Mother Courage and Her Children: Example of Theory and Practice of Epic Theater. Hollfeld (Beyer) 1976.

- Kenneth R. Fowler: The Mother of all Wars: A Critical Interpretation of Bertolt Brecht's Mother Courage and Her Children. Department of German Studies, McGill University Montreal, 1996 (dissertation).

- Werner Hecht : Materials on Brecht's “Mother Courage and Her Children” Frankfurt am Main 1964.

- Fritz Hennenberg : Dessau - Brecht. Musical work. Published by the German Academy of the Arts . Henschelverlag, Berlin (GDR) 1963.

- Fritz Hennenberg (ed.): Brecht song book. Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-518-37716-7 .

- Fritz Hennenberg: Simon Parmet, Paul Burkhard. The music for the premiere of “Mother Courage and Her Children” In: notate. Information sheet and bulletin from the Brecht Center of the GDR. Volume 10, 1987, No. 4, pp. 10-12. (= Study No. 21.)

- Fritz Hennenberg: poet, composer - and some difficulties. Paul Burkhard's songs for Brecht's “Mother Courage” In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung , March 9, 2002.

- Helmut Jendreiek: Bertolt Brecht: Drama of Change. Bagel, Düsseldorf 1969, ISBN 3-513-02114-3 .

- Jan Knopf : Brecht manual. Theatre. Metzler, Stuttgart 1986, unabridged special edition, ISBN 3-476-00587-9 , notes on Mother Courage, pp. 181–195.

- Gudrun Loster-Schneider: From women and soldiers: Balladesque text genealogies from Brecht's early war poetry. In: Lars Koch, Marianne Vogel (eds.): Imaginary worlds in conflict. War and history in German-language literature since 1900. Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-8260-3210-3 .

- Joachim Lucchesi : “Emancipate your orchestra!” Incidental music for Swiss Brecht premieres. In: Dreigroschenheft . 18th year, issue 1/2011, pp. 17–30 (previously published in: dissonance. Swiss music magazine for research and creation, issue 110 (June 2010), pp. 50–59).

- Krisztina Mannász: The epic theater using the example of Brecht's mother Courage and her children: The epic theater and its elements in Bertolt Brecht. VDM Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-639-21872-5 .

- Mautpreller, Joachim Lucchesi: The standard of compassion - found. In: Dreigroschenheft. 19th year, 2012, issue 1, pp. 11–20.

- Franz Norbert Mennemeier: Mother Courage and her children. In: Benno von Wiese (Ed.): The German Drama. Düsseldorf 1962, pp. 383-400.

- Joachim Müller: Dramatic, epic and dialectical theater. In: Reinhold Grimm: Epic Theater. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1971, ISBN 3-462-00461-1 , pp. 154-196.

- Klaus-Detlef Müller (Ed.): Brecht's "Mother Courage and Her Children" Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-518-38516-X (extensive anthology with essays and other materials).

- August Obermayer (Ed.): The dramaturgical function of the songs in Brecht's mother courage and her children. In: August Obermayer (Hrsg.): Festschrift for EW Herd. University of Otago, Dunedin 1980, pp. 200-213

- Teo Otto: sets for Brecht. Brecht on German stages: Bertolt Brecht's dramatic work on the theater in the Federal Republic of Germany. InterNations, Bad Godesberg 1968.

- Andreas Siekmann: Bertolt Brecht: Mother Courage and her children. Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-12-923262-1 .

- Dieter Thiele: Bertolt Brecht: Mother Courage and her children. Diesterweg, Frankfurt 1985.

- Günter Thimm: The chaos was not gone. An adolescent conflict as a structural principle of Brecht's plays. (= Freiburg literary psychological studies , Volume 7). 2002, ISBN 978-3-8260-2424-5 .

- Friedrich Wölfel: Bertolt Brecht - The song of the mother courage. In: Rupert Hirschenauer, Albrecht Weber (ed.): Paths to the poem. Volume II: Interpretation of Ballads. Schnell and Steiner, Munich / Zurich 1963, pp. 537–549.

Web links

- Bertolt Brecht. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Mother Courage and her children (synopsis) (PDF; 50 kB) Proseminar at the University of Würzburg

- Manfred Wekwerth: What does reality actually mean on stage? or The real chances of the theater. In: Marxistische Blätter , 4/2009

- detailed text on lit.de.

Individual evidence

- ↑ cf. Jan Esper Olsson: Bertolt Brecht: Mother Corage and her children . Historical-critical edition. 1981. Liber Läromedel, Lund; Suhrkamp, Frankfurt, p. 112.

- ^ Hanns Otto Münsterer: Bert Brecht. Memories from the years 1917–1922 . Berlin 1977, p. 28.

- ↑ Mautpreller, Lucchesi: The standard of compassion - found .

- ↑ Mautpreller, Lucchesi: The standard of compassion - found . For the Barbara song cf. Fritz Henneberg: Brecht Liederbuch , p. 375. For the song of the roses from the Schipkapass cf. Albrecht Dümling: Don't let yourself be seduced! P. 25.

- ^ Fritz Hennenberg: Brecht song book , p. 431.

- ↑ Simon Parmet: The original music for "Mother Courage". My collaboration with Brecht . In: Schweizerische Musikzeitung , vol. 97 (1957), issue 12, p. 466.

- ↑ Lucchesi: “Emancipate your orchestra!” , P. 22. Hennenberg: poet, composer - and some difficulties . 2002.

- ↑ Lucchesi, Shull: Music with Brecht . 1988, pp. 54f.

- ^ Hennenberg: Brecht song book , p. 430

- ↑ See e.g. B. Joachim Lucchesi: Sung Texts. Questions to the new Brecht research. In: Dreigroschenheft , 2/2007, pp. 26–33.

- ↑ The scene overview is printed in: Jan Esper Olsson: Bertolt Brecht: Mother Courage and her children. Historical-critical edition . Liber Läromedel, Lund; Suhrkamp, Frankfurt. 1981. p. 112.

- ↑ Dümling: Don't let yourself be seduced, p. 457.

- ↑ Quoted from Hennenberg: Brecht Liederbuch , p. 368 f.

- ↑ Cf. Dieter Baacke, Wolfgang Heydrich: Glück und Geschichte. Notes on the poetry of Bertolt Brecht . In: Text and criticism : Bertolt Brecht II, 1979, pp. 5–19, here: p. 11.

- ↑ Quoted from: Hennenberg: Brecht Liederbuch , p. 361.

- ^ Matthias Tischer: Composing for and against the state , p. 107.

- ^ Hennenberg: Brecht - Dessau , p. 227.

- ↑ Albrecht Dümling: Don't let yourself be seduced , p. 553.

- ^ Hennenberg: Brecht - Dessau , p. 227.

- ↑ See especially: Hennenberg: Brecht - Dessau , pp. 225–228.

- ↑ See for example Hennenberg: Brecht-Liederbuch , p. 367 (commentary on the ballad “Apfelböck or the lily on the field” from the same period).

- ^ Hennenberg: Brecht - Dessau , p. 227f and p. 406.

- ^ Gerd Rienäcker: Analytical remarks on orchestral music "In memoriam Bertolt Brecht" by Paul Dessau . In: Mathias Hansen (Ed.): Musical analysis in discussion . Berlin 1982, pp. 69-81; quoted here from: Tischer: Composing for and against the State , p. 108.

- ↑ Cf. Rienäcker, quoted from Tischer: Composing for and against the State , p. 108.

- ^ According to Tischer: Composing for and against the State , p. 108f.

- ↑ Tischer: Composing for and against the state , p. 108.

- ↑ Rienäcker, quoted from Tischer: Composing for and against the State , p. 109.

- ^ Daniela Reinhold: Paul Dessau. Documents on life and work . 1995, p. 73 (documents 97 and 98), see also Figure 22, which shows the title page of an early version of the suite. On In memoriam Bertolt Brecht and the processing of stage music there: Matthias Tischer: Composing for and against the state , in particular pp. 107–113.

- ↑ Cf. on Parmet and Burkhard in particular: Lucchesi: "Emancipate your orchestra!" .

- ^ Hennenberg: Dessau - Brecht , p. 449.