Martial

Marcus Valerius Martialis (German Martial ; * March 1, 40 AD in Bilbilis ; † 103/104 AD ibid) was a Roman poet who is best known for his epigrams .

Life

Most of the information about Martial is taken from his works. Since the author does not always agree with the people appearing in the poem, but the lyrical ego expresses itself in completely different characters, these dates should be treated with caution. The only source of the biography outside of his work is the obituary written by the younger Pliny (ep. 3,21).

Martial was born around 40 AD in Bilbilis (on the Cerro de Bambola near present-day Calatayud , northern Spain ). He attended a rhetorician and grammar school, where he discovered his literary talent. Between 63 and 64 AD he went to Rome and initially lived in rather poor conditions. At the beginning of the 80s AD, the literary production that we can understand begins, which extends approximately to the year 102 AD. In a poem he himself refers to his youthful poetry, of the existence of which we receive no reference outside of the epigram corpus.

Like many poets of his time, Martial was dependent on his friends and patrons , who mainly supported him financially. In his poems he likes to flirt with his penniless social status and thus creates the image of the “beggar poet”, which has not remained without consequences in literature. The name is probably an ironic exaggeration, because as early as 84 AD he owned an estate in Nomentum , later in Rome, and according to his own statements, he owned slaves and secretaries.

Martial also managed to gain a certain reputation among the emperors Titus (79–81) and Domitian (81–96) through poems of praise, which helped him to lead a relatively prosperous life. He was appointed to the military tribune and eques and had the right to three children . Despite this right, Martial's family circumstances remain unknown.

Under the emperors Nerva (96–98) and Trajan (98–117) the political situation in Rome changed. Both rejected panegyric and excessive praise. Probably for this reason Martial decided to return to his homeland around 98-100 AD. Once again he was supported by his patrons so that he could continue working on his works. However, it seems that his initial joy about returning soon turned into a longing for Rome. At least he writes in the Praefatio of the twelfth book that he lacks the inspiration from the audience in Rome. Martial died around 104 AD in his place of birth, Bilbilis.

Patrons and friends

Martial's important patrons and friends included Seneca , Pliny the Younger , Quintilian , Juvenal, and the emperors Titus and Domitian . Above all through the financial support, but also through the reputation that these contacts brought him, Martial managed to become one of the most important Roman poets.

However, his sometimes exaggerated flattery caused a few problems after Domitian's death. Emperor Nerva, who was involved in the murder of his predecessor, asked Martial to rewrite or destroy his poems of praise for Domitian. Martial obeyed this order only reluctantly (and only partially).

Even his departure from Rome was financed by patrons. So Pliny the Younger paid for his trip home while his patroness Marcella made an estate available to him.

Works

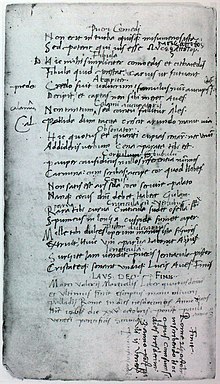

Martial's works are almost exclusively limited to epigrams. Models for his poetry were Catullus and Horace .

His main work comprised twelve epigram books.

Liber Spectaculorum (80 AD)

A collection of poems that were published under Emperor Titus for the opening of the recently completed Colosseum and with which Martial is likely to have started his career as a creator of epigram books.

Barbara pyramidum sileat miracula Memphis,

Assyrius iactet nec Babylona labor;

nec Triviae templo molles laudentur Iones,

dissimulet Delon cornibus ara frequens

aere nec vacuo pendentia Mausolea

laudibus inmodicis Cares in astra ferant.

Omnis Caesareo cedit labor Amphitheatro,

unum pro cunctis fama loquetur opus.

Silence the strange Memphis of the miracle of the pyramids ,

nor does Assyrian toil brag about Babylon ;

Soft Ionians, do not boast of the temple of Trivia (Trivia = nickname of Diana),

and the horned altar often hides its Delos !

The mausoleum that juts out into the airy void,

Karer, does not lift it up to the stars in excessive praise!

Any achievement dwindles in front of the emperor's amphitheater In the

future, one work alone will celebrate fame instead of all.

The book is incomplete in a medieval floral manuscript and by no means has come down to us in the original order of the poems. In the 30 or so surviving epigrams, the author praises the emperor and the building, and the “sights” in the arena (punishments for crimes, fights between gladiators ) are extensively described - often with frightening indifference or even malicious glee for the modern audience .

Xenia and Apophoreta (84/85 AD)

These works are poems accompanying small gifts that were given to friends and guests, especially at the Saturnalia Festival. The Xenia refer almost without exception to culinary delights and in this way offer an insight into Roman gastronomy, while the Apophoreta have all possible points of contact (including literary associations).

Epigrammaton libri duodecim (approx. 85–103 AD)

A collection of twelve books with a total of 1557 epigrams. Often the works mentioned above are also included, which is why 14 or 15 books are also spoken of.

Martial described in most of his epigrams the everyday life of the Romans and presented it ironically, satirically and sometimes vulgar. Important topics are the difference between poverty and wealth, righteousness and vice as well as the light and dark sides of life. He also characterizes and mocks conspicuous Roman types with a few words and pointed puns, such as incompetent doctors, untalented poets, betrayed husbands and vain beauties, although he does not address anyone personally, but uses meaningful names. An example:

Uxor, vade foras aut moribus utere nostris:

non sum ego nec Curius nec Numa nec Tatius.

Me iucunda iuvant tractae per pocula noctes:

tu properas pota surgere tristis aqua.

Tu tenebris gaudes: me ludere teste lucerna

et iuvat admissa rumpere luce latus.

Fascia te tunicaeque obscuraque pallia celant:

at mihi nulla satis nuda puella iacet.

basia me capiunt blandas imitata columbas:

do mihi the aviae qualia mane soles.

Nec motu dignaris opus nec voce iuvare

nec digitis, tamquam tura merumque pares:

masturbabantur Phrygii post ostia servi,

Hectoreo quotiens sederat uxor equo,

et quamvis Ithaco stertente pudica solebat

illic Penelope semper habere manum.

Pedicare negas: dabat hoc Cornelia Graccho,

Iulia Pompeio, Porcia, Brute, tibi;

dulcia Dardanio nondum miscente ministro

pocula Iuno fuit pro Ganymede Iovi.

Si te delectat gravitas, Lucretia toto

sis licet usque die: Laida nocte volo.

Wife, get away if you don't accept my customs:

I'm not a Numa after all, Curius , not Tatius .

I am delighted to spend the night at the cup in lust:

you drink, sad people, water, and hurry away.

You love the dark: But I want to float by the light of the lamp,

which allows a free view of bodies while enjoying love.

Tunics , coats and bandages envelop you, dark in color:

on the other hand, one girl is never enough for me naked.

I am delighted by the kisses that tender doves give:

What I receive from you was once upon my grandmother.

Motionless you lie in bed, not a word, not caressing fingers

as wanted incense you burn, and sacramental wine sacrifice to:

Behind the door masturbated the Phrygian servants when riding

like a horse of Hector's wife was sitting,

and liked her Ithaker also in bed enormous snore,

withdrew Penelope not yet a helping hand to him.

What do you refuse me: It offered Cornelia the Gracchus ,

Julia the Pompei , and Brutus the Porcia .

Ere the Dardanian cupbearer mixed the sweet Cups,

the Jupiter to services was Juno , instead Ganymede .

If you are so delighted by honesty, you may always be

a Lucretia during the day : I want a Lais at night.

Although there are many names in Martial's epigrams, it is likely that many of the people addressed were invented or the names were changed, although he retained the number of syllables, because Martial treated at least the powerful of his time with great caution. Often, however, there is praise for the emperors Titus and Domitian.

meaning

Martial is considered the master of epigram poetry, which he made socially acceptable in Rome. His works offer a good insight into everyday life in Rome at the time. In particular, the epigrams about social discrepancies met with a great response during the poet's lifetime. They were also very popular in late antiquity , the Middle Ages and the Renaissance .

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729–1781) took Martial's works as a model for his epigrams. Martial's reception history in the Romance literatures is even more important.

The term plagiarism is said to go back to an epigram in which Martial insulted a poet who had pretended to be the author of his “little book” as plagiarius (literally “ robber ”, “slave trader”).

Editions and translations

- DR Shackleton Bailey (Ed.): M. Valerii Martialis epigrammata . Teubner, Stuttgart 1990 (critical edition)

- M. Valerius Martialis: epigrams . Selected, imported and come by Uwe Walter . Schöningh, Paderborn 1996.

- Martial: epigrams . Translated from Latin and edited by Walter Hofmann. Insel, Frankfurt / Leipzig 1997

- M. Valerius Martialis: epigrams . Latin-German, ed. and over. by Paul Barié and Winfried Schindler. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 1999. (3rd, fully revised edition Akad.-Verl., Berlin 2013)

- Marcus Valerius Martialis: Martial for contemporaries. Selected, translated into German and provided with drawings by Fritz Graßhoff . Eremiten Presse, Düsseldorf 1998. ISBN 3-87365-315-X .

- Christian Schöffel: Martial, Book 8. Introduction, text, translation, commentary . Steiner, Stuttgart 2002.

- Martial: epigrams . Lat./Dt., Transl. and ed. by Niklas Holzberg . Reclam, Stuttgart 2008.

literature

Overview display

- Michael von Albrecht : History of Roman literature from Andronicus to Boethius and its continued effect . Volume 2. 3rd, improved and expanded edition. De Gruyter, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-026525-5 , pp. 877-892

Introductions, overall presentations, investigations and comments

- Farouk Grewing: Martial, Book VI. A comment . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1997.

- Walter Burnikel: Quintilian and Martial . In: Ders .: Quintilian. Pedagogical texts from antiquity (Exemplary Series Literature and Philosophy; Vol. 34). Sonnenberg, Annweiler 2013, ISBN 3-9332-6474-X , pp. 88-95.

- Christian Gnilka : Martial about his art . In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie / NF ; Vol. 148 (2005), pp. 293-304, ISSN 0035-449X ( online ; PDF; 57 kB).

- Fiona Pitt-Kethley : Martial . In: Dies .: The literary companion to sex . Arcadia Books, New York 2014, ISBN 978-1-85619-127-2 .

- Otto Seel : Approach to a martial interpretation . In: Antike und Abendland , Vol. 10, 1961, pp. 53-76, ISSN 0003-5696

- Paul Barié: Martial. Reality reflected in the Roman epigram (Exemplary Series Literature and Philosophy; Vol. 17). Sonnenberg, Annweiler 2004 ISBN 3-933264-34-0

- Niklas Holzberg : Martial and the ancient epigram. An introduction . 2nd Edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2002, ISBN 978-3-534-25137-7 .

- Peter Howell: Martial . Bristol Classical Press, London 2009, ISBN 978-1-85399-702-0 .

- Herrmann Mostar : Cheeky and frivolous according to Roman custom M. Val. Martialis' epigrams . Ullstein, Frankfurt / M. 1992, ISBN 3-548-22671-X (EA Stuttgart 1971).

- Helmut Offermann (arr.): Martial Epigrams. “Parcere personis, dicere de vitiis” (Antiquity and the present; Vol. 17). 2nd Edition. Buchner, Bamberg 2007, ISBN 978-3-7661-5967-0 .

- Carsten Schmieder: For the constancy of erotic experience: Martial, Juvenal, Pasolini . Hybris, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-939735-00-7 .

- John Patrick Sullivan: Martial. The unexpected classic. A literary and historical study . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1991, ISBN 0-521-26458-8

reception

- Patricia Watson, Lindsay Watson: Martial (Marcus Valerius Martialis). Epigrammata. In: Christine Walde (Ed.): The reception of ancient literature. Kulturhistorisches Werklexikon (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 7). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2010, ISBN 978-3-476-02034-5 , Sp. 523-536.

Web links

- Literature by and about Martial in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Martial in the German Digital Library

- Martial epigrams (Latin)

- Martialis epigrammata (Latin)

- Martial translations

Remarks

- ↑ Martial, Epigrams 11,104.

- ↑ Kurt-Henning Mehnert: "Sal Romanus" and "Esprit Français". Studies on martial reception in France in the 16th and 17th centuries (= Romanistic attempts and preparatory work , vol. 33). Romance Studies Seminar, Bonn 1970 (also dissertation, University of Bonn 1969).

- ↑ Martial, Epigrams 1.52.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Martial |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Martialis, Marcus Valerius |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | roman poet |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 40 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bilbilis |

| DATE OF DEATH | at 103 |

| Place of death | Bilbilis |