Migration in South Korea

Migration in South Korea refers to immigration and emigration in that state since the end of the Pacific War .

Between the armistice in the Korean War in 1953 and around 1985, South Korea had a significantly negative migration balance . Immigration by foreigners did not begin on a larger scale until the 1990s. From 1987 tourist travel was allowed for people over the age of 44; South Koreans have only had full tourist freedom since the Olympic Games in Seoul in 1988 . The migration surplus remained low for a long time, and South Korea is still not a country of immigration, which is also due to the restrictive immigration legislation.

Korean diaspora

Koreans abroad do not have an automatic right to return home. B. Jews to Israel or Germans from Eastern Europe according to Art. 116 GG. The provisions of the Overseas Migration Act for returnees and the Legislation on Immigration and Legal Status of Overseas Koreans ("Overseas Korean Act") regulate the relationship between the state and its citizens living abroad if they emigrated after 1948.

It was estimated in 2011 that there are approximately 7.25 million people of Korean origin or ancestry worldwide outside of South Korea. A good 60 percent have received the citizenship of their host country. Around 1.1 million had permanent residence permits and a good 1.6 million temporary residence permits. The last two groups have been allowed to vote in Korea since 2012.

In 2011, the Foreign Ministry estimated that the diaspora was distributed as follows: 56% (4 million) in Asia, of which 2.7 million in China and 950,000 in Japan; 34% in America (2.5 million), of which 2.1 million in USA, 230,000 in Canada and 112,000 in Latin America; 9% in CIS (535,000) and 121,000 in the rest of Europe.

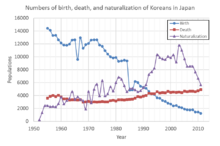

Japan returnees and Zainichi

After Korea became part of the Japanese Empire in 1905/10 , its inhabitants were subjects. The Japanese nationality depends on the place where the Koseki family register is kept. From 1895 to 1947 a distinction was made between “inner” (for real Japanese of the main islands) and “outer” for colonial subjects in Formosa and Korea, etc. At the end of the war in September 1945 there were about 2.4 million Koreans on the main Japanese islands.

After massive discrimination was systematically practiced by the Japanese administration soon after the end of the Pacific War, around 650,000 Koreans remained in Japan in 1947. Their descendants are called Zainichi ( 在 日韓 国人 ). As soon as the Japanese government regained its sovereignty through the peace treaty of San Francisco , it finally revoked the Japanese citizenship from all persons with “external” family registers. Residence permits were only issued under minor conditions. For example, anyone who had only briefly visited Korea in 1945–51 was expelled as “illegal immigrants who came after 1945”. In the early 1950s, " social parasitic campaigns " followed repeatedly . They went further and initially excluded local Koreans from the state, then rudimentary health system and, for years, from attending state schools. Until the reform of the law of residence in 1989, most Zainichi had to apply for an extension of their residence permit every six months. Only since then have they been able to obtain permanent residence rights. Anyone who declares their home in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), which is not recognized by Japan , still has the status of a stateless Chōsen-seki ( 朝鮮 籍 ). Around 30,000 people were affected in 2017.

The repressive state measures resulted in hundreds of thousands "voluntarily" returning to Korea, both in the south and a good 93,000 in the north of the devastated peninsula, particularly in the 1950s. The expulsion represented a particular hardship for the large group of people who came from the island of Cheju . There the dictator Rhee Syng-man, appointed by the Americans, organized a massacre in 1948 in which 270 of 400 villages and their inhabitants were destroyed.

The politically correct Korean name for Koreans living in Japan is jaeil gyopo ( 在 日 僑胞 / 재일 교포 ).

Manchuria

After the founding of the Manchukuo state in 1936, the Japanese government massively encouraged the immigration of its subjects, including, of course, numerous Koreans to Manchuria .

After the hostilities in the Pacific War ended in September 1945, the repatriation of Japanese from there was chaotic and slow; Koreans were not officially bothered at all. The Manchurian provinces were also fiercely contested when the Chinese nationalists withdrew in 1948/49. 63,000 Koreans fought in the ranks of the People's Liberation Army, especially the 4th Army. Others supported the liberation in local militias.

The former Japanese subjects of Korean origin who remained in the region form the basis of the population group known as Chosŏnjok , along with a few who have lived here since the 1860s . After the liberation, they became Chinese citizens, but in the following generations they mostly knew the Korean language.

Siberia

The Korean population known as Korjo-Saram lives primarily in the Primorye ( Primmorskii krai ) region. Most of them are descendants of emigrants from the northern Hamgyŏng province . Soviet censuses found just under 87,000 Koreans in 1926, 91,450 in 1959, 101,400 in 1979 and 2010 (Russia only): 146,000.

A smaller group lives on Sakhalin . They came from the southern provinces of Kysngsang and Chŏlla at the time of the Japanese administration of South Sakachalin through Japan as Karafuto Prefecture . Of the Sakhalin Koreans, around 150,000 at the end of the war, around 43,000 remained after 1945. Their number is estimated today at 38,000–55,000.

As part of the Soviet nationality policy, many Koreans were resettled to Central Asia in 1937. Korean nationality remained on the national passports. Some returned from 1956. But their number remained low at 8900 until 1989.

Like many Russian- Germans, these ethnic Koreans have little or no knowledge of their “mother tongue.” Insofar as members of these population groups migrate to South Korea, they are normally included in the statistics as citizens of the successor states of the Soviet Union. So lived z. B. 2005 about 15,000 Koreans with Uzbek citizenship in South Korea.

Marriages and adoptions

As in other conquered countries, the presence of thousands of young American men, supposedly wealthy, resulted in "fraternization", which until well into the 1970s often led to weddings for Korean women for reasons of propriety.

The number of marriages with foreigners and subsequent emigration has been decreasing continuously since 1981. In that year there were 6187, in 1991 only 2365, in 2001 then 1197 and in 2010 only 89.

The status of people marrying into South Korea was not regulated until 2009 by the Support for Multicultural Families Act .

On the other hand, as a result of the war, thousands of orphans remained in the country from the mid-1950s. Thousands were adopted mainly to the United States. Due to the military presence, a number of “occupation children” remained behind for decades. In the traditionally conservative Korean worldview, single mothers are not envisaged, so many babies have been put up for adoption.

Before 1999, adopts abroad were only allowed to stay in Korea with status F-1 or F-2 (family or sponsor visa). Since 1999, Koreans abroad (F-4) have been able to stay in the country for up to three years under easier conditions and can receive health insurance coverage after 90 days. However, they are not allowed to take on low-skilled jobs.

The number of international adoptions fell sharply after 1988 and has been limited to a few western countries since 2006.

Emigration Act from 1962

At the end of the 1950s, cases of “hidden emigration” ( wijang imin ) occurred e.g. B. under a false name or by fake marriage. In order to steer this into controlled channels and at the same time to reduce the number of unemployed, which had risen due to rural exodus, an emigration law was passed in 1962 that allowed people to leave the country in an orderly manner and at the same time regulated intermediaries. Potential emigrants had to meet certain conditions, such as military service. They were only allowed to take out a limited amount of money. These rules were defused in 1981.

A relevant department in the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs was responsible for promoting emigration. As the first group, 17 families with 92 people were sent to Brazil as farm workers. The government bought land for peasant new settlers in Paraguay, Bolivia and Argentina. This area also includes special cases such as the recruitment agreement between the Federal Republic of Germany and South Korea , which brought miners first, then nurses to the FRG as contract workers. Together, especially from 1962 to 1965, there were almost 9,900 people.

After a slow start, and as a result of a change in US immigration laws in 1965, there was a rapid increase in the number of emigrants, so that in the 1970s around 30,000 people moved to the USA annually. The popularity of Canada as a target country increased after 1985, at the same time Australia became popular, which for a few years increasingly opened up to Asian immigration. Around this time, Latin America's popularity as a destination declined significantly. In Argentina, 85% of Koreans now live in the province of Buenos Aires, especially the Koreatown of the capital, Buenos Aires . Paraguay and Brazil had also accepted thousands of immigrants.

Responsibility was transferred to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1984. Since the first half of the 1980s, when 30,000–35,000 Koreans emigrated annually, the numbers have been falling continuously. Ten years later, 15,000 Koreans left their country permanently. In 2005 there were 8,200, five years later the number fell to under a thousand.

Korean international students

South Korean students have only been allowed to go abroad since 1980. Since the higher education system in South Korea is paid for on the one hand, and on the other hand, as in Japan, remains closed due to difficult entrance exams, numerous Koreans study in America. Especially among students who achieve higher degrees in natural sciences (3,000–4,000 Korean doctorates annually), it has been shown that a good half do not return home, which is a brain drain that damages the economy.

Immigration

Entry, exit and registration requirements for foreigners were first regulated by a law in 1949. The provisions of the frequently amended Immigration Control Law, issued in 1963, are much more detailed .

POWs from the north

When the end of the fighting in the Korean War was foreseeable from 1952, numerous North Korean prisoners of war, most of them in the Koje prisoner-of-war camp, were subjected to strong psychological pressure to prevent them from returning to their homeland, where they were urgently needed for reconstruction . In the south, at least 102,000 of the former soldiers (forcibly) remained.

Refugees from the Democratic People's Republic of Korea

When the economic situation in North Korea deteriorated in the 1990s, more and more people from the north left illegally.

The People's Republic of China does not recognize republic refugees from North Korea. They are deported back to their homeland as illegally entered. In order to get to South Korea, they have to turn to commercial intermediaries or charitable organizations that will clandestinely bring them to a third country.

Under international law, North Korean refugees ( talbukja ) are not eligible for recognition under the 1951 Refugee Convention . However, the UNHCR has seen them as a “group of concern” since 2003, so that they can be accepted as “mandate refugees”.

Those who came from North Korea are first questioned intensively by the state security organs. If they are allowed to stay, they will be given a 12-week integration course in a re-education camp set up in Hanawon in July 1999 . You will also receive welcome money, the amount of which in 2016 was at least € 14,500.

Many of the people from the north complain about a lack of promotion opportunities or discrimination. For many, it is a reason to move to third countries and try to be recognized as political refugees there.

Chosŏnjok

Chosŏnjok ( Joseonjok ) is the name for Koreans living in China. They were the Autonomous District Yanbian Koreans in eastern Manchuria province of Jilin set up (jap. Kirin). Their share of the local population is over 35%.

Since the normalization of relations with the People's Republic of China in 1986/92, orderly travel has been possible. Before 1990, Chosŏnjok had the option of facilitated permanent residence and citizenship if they could prove that their ancestors were anti-Japanese fighters.

From 2002 to 2007, ethnic Koreans were able to work in Korea for two years for over 40 years. You should especially positions in building cleaning, care for the elderly and the like. fill out similar services.

These Koreans with Chinese citizenship (including those from the CIS countries) can today, if they are 25 years old, receive a work permit (H-2) called Bangmun chuieop for training in 26 defined industries (including construction), the is valid for a maximum of five years, but must be extended after three years. The award is dependent on a language test and an annual quota, if necessary the lot will decide. After the expiry, the journey home is compulsory; a new application can be submitted after one year of absence at the earliest. In times of economic boom the rate was 280,000–300,000 per year, about a quarter of all foreign workers. During economic crises, around 2012, it was cut back sharply.

Many of those recruited in this way try to change their residence status from H-2 to E-7 (“special professions” since 2011) in order to avoid leaving the country.

Guest workers

Before the economic boom of the 1990s, there were hardly any non-Korean immigrants, apart from well-qualified specialists, teaching staff or business people. The labor requirements of the export-oriented industrialization program, which was started around 1960, could be met by rural refugees.

A “trainee” program was created in 1991 and expanded in 1993, which did not recognize guest workers as full-fledged workers. A system of work permits was formalized only in 2003 and then in 2007 by working visas for ethnic Koreans (H-2).

The practice of awarding work and residence permits is used to control the demand on the labor market. In some sectors, the employment of foreigners is completely prohibited. This includes the construction industry as well as the nightlife sector. This is probably also because the influence of Korean mafiosi ( geondal or jopok ) is great here. Family reunification is not planned.

The different types of work and residence permits are very differentiated. Highly qualified people receive categories E-1 to E-5. There is also category E-6 for “artists and entertainers.” The latter is mainly used by women from (South) East Asia and is often misused in the entertainment industry for prostitution and similar illegal activities. In 2006 about 145,000 Han Chinese were working in the country.

Employment contracts are usually concluded for one year, then extended accordingly. In most cases, a change of job, especially to another branch, requires approval. Employers have to pay the repatriation costs. a. guarantee in the form of insurance. Almost all categories of work permits are limited in time and are difficult to extend, especially for low-skilled jobs. So z. B. the “general worker visa” E-9, which is only granted to citizens of 15 selected Asian developing countries, for three years. It can be extended once for 22 months. At the end of 2010, 217,000 workers had this residence permit, which corresponds to around a tenth of the guest workers in the country.

Especially in smaller factories, guest workers are paid far less than local workers at 65–70%. Although Chosŏnjok are preferred because of their more flexible work permits and language skills, it is precisely those “to be qualified” (category D-3 or D-4) that are often exploited.

Guest workers have had the right to join trade unions since 2009. In the various branches of social security they are insured like locals, but there are special regulations depending on the residence status.

Foreigners with a residence permit for more than 91 days usually have to register and receive a corresponding ID-like card. You must then apply for a re-entry permit before traveling abroad .

Illegal immigration

Most illegal immigrants have not left the country after their (tourist) residence permit has expired. Especially in the entertainment industry, which is closed to foreigners (ie primarily entertainment venues, "massage" salons, etc.), the proportion of people from Southeast Asia is particularly high. Employers face fines or up to three years in prison.

From China in particular there is illegal entry every year, mostly with small fishing boats. This smuggling of people, the number of people seized has fallen sharply since 2005, is well known and is tolerated by not looking too closely for political reasons.

Foreign children living in the country are allowed to attend elementary and secondary schools, i. H. attend up to 9th grade without asking about the parents' residence status.

There are always campaigns to reduce illegal aliens in the country. So in 2003 and again in 2017-18, when it was assumed that one tenth of guest workers were illegal. One such program was the "voluntary departure program" ( Jajin guiguk program ) aimed at Chosŏnjok without papers in 2005 , which guaranteed the hitherto illegals that they could come back for three years after their return home and proper application. As a rule, generous departure deadlines or amnesties are granted.

The 2018/19 amnesty is aimed primarily at Southeast Asians. They are only guaranteed the possibility of trouble-free departure and only if they did not work in construction or in the entertainment industry. Before leaving the country, it is also checked whether the foreigner is suspected of having committed a crime.

The advantage of facing up for the foreigner is that he is not considered a deported person who is forbidden to re-enter for life.

naturalization

→ Main article: Korean citizenship

Students and Working Holiday

Foreign students (visa D-2 or D-4) can work up to 20 hours after a certain waiting time and with the permission of the institute.

South Korea has concluded an agreement on working holidays for young people with some western countries (visa H-1). With this status, which is usually limited to one year, only a few hundred people reside in the country. Here, too, employment bans apply to the entertainment industry and in areas that require higher qualifications (i.e. visa category E).

Asylum seekers

South Korea joined the 1951 Refugee Convention. The number of asylum applications (apart from North Koreans who have fled the republic) is and remains low, as is the recognition rate: of 2915 applications in 1994-2010, 423 pending cases, only around 12% were approved (222 recognitions (8.9%) and 136 Permits to stay on humanitarian grounds (5.5%)).

Many applicants use the possibility of visa-free entry to the holiday island of Jeju . The majority of the population is opposed to asylum seekers, especially from Muslim countries.

See also

literature

- Chang-Gusko, Yong-Seun; Unknown diversity: insights into Korean migration history in Germany; Cologne 2014 ( DOMiD )

- Freemann, Caren; Making and Faking Kinship: Marriage and Labor Migration between China and South Korea; Ithaca 2011 (Cornell University Press); ISBn 9780801449581

- Hahm hanhee; Migrant Laborers As Social Race In The Interplay Of Capitalism, Nationalism, and Multiculturalism: A Korean Case; Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic, Vol. 43 (2014), No. 4, pp. 363-99

- International Organization for Migration; Migration Profile of the Republic of Korea; IOM MRTC Research Report Series, No. 2011–01 (Jan. 2012)

- Kang Ui-seon; Changes in South Korean Emigration Policy in the 1970s - Focusing on Emigration to North America; Seoul 2015

- Kim Hee-Kang; Marriage Migration Between South Korea and Vietnam: A Gender Perspective; Asian Perspective, Vol. 36 (2012), No. 3, pp. 531-563

- Oh, Arissa; New Kind of Missionary Work: Chrisitians, Christian Americanists, and The Adoption of Korean GI Babies, 1955–1961; Women's Studies Quarterly, Vol. 33 (2005), No. 3/4, pp. 161-88

- Park Hyun-gwi; Migration Regime among Koreans in the Russian Far East; Inner Asia, Vol. 15 (2013), No. 1, pp. 77-99

- Kyeyoung Park; A Rhizomatic Diaspora: Transnational Passage And The Sense of Place Among Koreans in Latin America; Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic, Vol. 43 (2014), No. 4, pp. 481-517

- Jeongwon Bourdais Park; Identity, policy, and prosperity: border nationality of the Korean diaspora and regional development in Northeast China; Singapore 2018; ISBN 978-981-10-4849-4

- Seol Dong-hoon; Skrentny, John; Ethnic return migration and hierarchical nationhood: Korean Chinese foreign workers in South Korea; Ethnicities, Vol. 9 (2009), No. 2, pp. 147-174

- Song, Doyoung; The Configuration of Daily Life Space for Muslims in Seoul: A Case Study Of Itaewon's "Muslims' Street;" Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic, Vol. 43 (2014), No. 4, pp. 401-40

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d International Organization for Migration; Migration Profile of the Republic of Korea; IOM MRTC Research Report Series, No. 2011-01 (Jan. 2012)

- ↑ Summarized from the introduction by: Morris-Suzuki, Tessa; Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan's Cold War; Lanham 2007; ISBN 9780742554412 .

- ↑ General: Park Hyun-gwi; Migration Regime among Koreans in the Russian Far East; Inner Asia, Vol. 15 (2013), No. 1, pp. 77-99

- ↑ Oh, Arissa; New Kind of Missionary Work: Chrisitians, Christian Americanists, and The Adoption of Korean GI Babies, 1955-1961; Women's Studies Quarterly, Vol. 33 (2005), No. 3/4, pp. 161-88

- ^ Onward Migration: Why Do North Korean Migrants Leave South Korea? (2018-02-26).

- ^ Act on Foreign Workers' Employment

- ^ Tough South Korean immigration screening causes social media furore (2017-05-18).

- ↑ Half a million South Koreans sign petition against immigration policy (2018-07-03).

Web links

- Korea Immigration Service (출입국 · 외국인 정책 본부)

- Emigration Act (Act No. 1030, Mar. 9, 1962), as amended, engl. Practice

- English law database

- South Korea Immigration Detention Profile