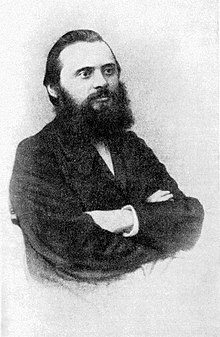

Mili Alexejewitsch Balakirew

Mili Alexeyevich Balakirev ( Russian Милий Алексеевич Балакирев , transliteration Mily Balakirev Alekseevic ; also Mily Balakirev ; * December 21, 1836 . Jul / 2. January 1837 greg. In Nizhny Novgorod , † May 16 jul. / 29. May 1910 greg. In Saint Petersburg ) was a Russian composer , pianist and conductor .

Life

Balakirev, the son of a civil servant and a pianist, received his first piano lessons from his mother. Through his teacher Karl Eisrich , he made the acquaintance of the music-interested landlord Alexander Ulybyschew around 1850 , who hired him as a pianist and conductor. In 1853 he and his friend, the later writer Pyotr Boborykin , attended the University of Kazan as a non-matriculated mathematics student, made a name for himself in Kazan as a pianist and gave some piano lessons. In 1855 Ulybyshev took him to St. Petersburg, where Balakirew got in touch with Mikhail Glinka and was enthusiastic about his vision of national Russian music. Glinka's intercession opened up wider circles of St. Petersburg musical life for Balakirew, so that in the following years he was able to get to know the later members of the so-called Mighty Heap . After joining Alexander Borodin in late 1862 , the formation of the Group of Five was complete. Balakirew took on the function of a teacher and mentor and supervised his compositional inexperienced friends by giving them instructions on how to write symphonies . In the same year he founded the Free Musical School as a competing institution to the Saint Petersburg Conservatory . At the free school he became assistant to the director Gawriil Lomakin . He also undertook in the 1860s several trips through the Caucasus and the Volga region to, folk songs to collect. From 1867 to 1869 he led the concerts of the Russian Music Society as the successor to Anton Rubinstein .

Due to a lack of public recognition and the increasing emancipation of his students, Balakirew fell into a deep crisis of meaning around 1870, which was expressed, among other things, in religious fanaticism. In addition, he stopped giving concerts and composing, in 1873 gave up the management of the musical free school to Rimsky-Korsakov and took a job as a railway official. It was not until 1876 that he turned back to music. In 1881 he was commissioned to publish the newly harmonized Russian Orthodox liturgy and in the same year he took over the management of the free musical school, which he held until 1908. Two years later he also became the conductor of the Hofsängerkapelle, which he remained until 1894. This year he had his last public appearance as a pianist in Żelazowa Wola , the birthplace of Chopin , on the occasion of the inauguration of a monument to the Polish composer. A pension of 3000 rubles annually from the court choir enabled Balakirev to live a largely carefree life. In the last years of his life he was very productive as a composer and completed some works, some of which he had started several decades ago.

His grave is in the Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg. In his honor, the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union named the Balakirev Glacier in Antarctica after him in 1987 .

Audio language

As a trained pianist, Balakirew initially followed the example of Frédéric Chopin and composed brilliant salon pieces. The encounter with Michail Glinka caused a change of heart. From now on he turned to the creation of an original Russian national style, which v. a. distinguished by the use of Russian songs and dances. This brought about a previously unknown use of church modes and unusual harmonies . In addition, a preference for orientalisms catches the eye, especially for melodies from the Caucasus. He was also based on Franz Liszt , whose influence was less stylistically than in the design, i.e. H. in the choice of genre, in the processing of themes and in the piano setting. So Balakirew developed a deeply Russian music based on Mikhail Glinka, which saw itself in contrast to Western (and especially Italian) music. Due to his quality as the leading figure of the “Mighty Heap”, Balakirew was able to pass on his ideals to other composers, with whom he was to decisively shape Russian music. The problem with his teaching was v. a. the renunciation of technical exercises and music theory . Balakirew himself had never received composition lessons, but acquired his knowledge by reading scores , etc. Anyway, he believed that technical exercises were a hindrance to inspiration and would "westernize" the music. However, the lack of technical skills sometimes caused considerable problems for his students.

meaning

Balakirew is of great importance as the founder of an entire epoch. The composer Balakirev is hardly represented in the concert halls today, although his works show great originality and good technique. The reason for this neglect can be seen historically: In the 1860s, Balakirew mainly turned to promoting his fellow campaigners, but composed only a little himself and mostly left his compositions unfinished. In the following years he got into the above. Crisis, and it was not until the 1880s that he began composing again. Now he went back to his incomplete works, but his style did not change. As a result, his works, which were only now completed and performed, were no longer up to date. Had Balakirev performed them as early as the 1860s, they would have gone down in history as revolutionary pioneering acts. But that left him with the lot of the late arrival. Most of his quite remarkable compositions have therefore received little attention to this day.

One of his most popular and most played compositions today is the piano fantasy Islamej , which demands extremely virtuoso dexterity from the concert pianist and is even considered to be one of the most technically demanding piano pieces of all. There are also transcriptions for orchestra of these compositions (by Sergei Lyapunow, among others).

Works

- Orchestral works

- Symphony No. 1 in C major (1864–66, 1893–97)

- Symphony No. 2 in D minor (1900-08)

- Suite in B minor (1901-08, completed by Sergei Lyapunow )

- Overture on a Spanish Marching Theme, Op. 6 (1857, rev. 1886)

- Russia ( Russian Русь ), symphonic poem (1862–64 under the title 1000 years , rev. As Russia 1884)

- In Bohemia , Overture (1866/67)

- Tamara , symphonic poem (1867–82)

- Piano Concerto No. 1 in F sharp minor op.1 (1855/56)

- Piano Concerto No. 2 in E flat major (1861/62, 1909/10, completed by Sergei Lyapunow)

- Grande fantaisie on Russian folk song themes for piano and orchestra in D flat major op.4 (1852)

- Incidental music

- King Lear , music to Shakespeare's tragedy (1857–61, rev. 1902–05)

- Vocal music

- Cantata for the unveiling of the Glinka monument in Petersburg for soprano, choir and orchestra (1902-04)

- Choirs

- Songs

- Folk song arrangements

- Piano and chamber music

- Sonata in B flat minor, Op. 5 (1855/56)

- Sonata in B flat minor (1900-05)

- Islamej , oriental fantasy (1869, rev. 1902)

- Toccata in c sharp minor (1902)

- 7 mazurkas

- 7 waltzes

- Nocturnes, Scherzi and other pieces

- Octet for flute, oboe, horn, violin, viola, violoncello, double bass and piano in C minor, Op. 3 (1850–56)

- Romance in E major for cello and piano (1856)

literature

- Sigrid Neef : The Russian Five: Balakirew - Borodin - Cui - Mussorgsky - Rimsky-Korsakov. Monographs - documents - letters - programs - works . Ernst Kuhn Verlag, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-928864-04-1 .

Web links

- Catalog raisonné

- Piano Society - Balakirev - Free recordings

- www.kreusch-sheet-music.net - Sheet music in the public domain by Mily Alexejewitsch Balakirew

- Sheet music and audio files by Mily Balakirew in the International Music Score Library Project

Remarks

- ↑ The word " Русь " in the original title can be translated as " Rus " or " Russia " depending on the context . Russia is also often used as a work name .

Individual evidence

- ^ Helmut Scheunchen : Lexicon of German Baltic Music. Harro von Hirschheydt publishing house, Wedemark-Elze 2002. ISBN 3-7777-0730-9 . P. 62

- ↑ See, for example: Mily Balakirev, Complete Piano Works in 5 Volumes. Koenemann Music Budapest.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Balakirew, Mili Alexejewitsch |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Бала́кирев, Ми́лий Алексе́евич (Russian); Balakirev, Milij Alexeevič (scientific transliteration); Balakirev, Mili |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian composer, pianist and conductor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 2, 1837 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Nizhny Novgorod |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 29, 1910 |

| Place of death | St. Petersburg |