Modulation (music)

In music theory , the word modulation describes the prepared transition from one starting key to another basic key and thus also the transition to a new tonic . Modulations one often detects notation technically the appearance of the typical for a certain key accidentals (accidents) in the course of the song. A modulation that has taken place can be recognized even better by the accidentals - these are usually accompanied by vertical double lines to emphasize the musical caesura in a complementary way. These accidentals do not always appear (as in many of Scarlatti's sonatas, as well as in many later sonata expositions, such as that in Mozart's Sonata No. 16 in C major).

If the target key is fixed by a cadence, one speaks of a real modulation ; if it is left immediately after it is reached , it is called a vague modulation . A series of modulations taking place immediately one after the other - with or without consolidation of temporary tonal centers - is called a modulation chain .

If the key change takes place without preparatory or transitional steps, this is not called modulation, but shifting . A modulation that occurs without a final cadence and does not lead out of the original key is called evasion .

In musical practice and theory, a distinction is made between several types of modulation:

- Diatonic modulation

- Chromatic modulation

- Enharmonic modulation

- Sound center introduction

- Direct modulation (in German-speaking countries mostly called backward movement and often viewed rather distantly from the term 'correct modulation')

Modulation in the melody

With many folk songs or chorals, modulation is already given by the melody.

Example:

The modulation description here is just an example of what modulation can be expected. A composer has many possibilities to interpret the harmonies in a polyphonic setting.

Modulation scheme

First, the original key is consolidated. This can be done through a cadence or simple dominant tonic combinations. This is followed by the actual modulation step, the transition to the target key. Finally, the target key is confirmed if it is a real modulation .

Modulation techniques

A distinction is made between the following modulation techniques:

Diatonic modulation

The diatonic modulation makes use of the fact that different keys have common triads. These triads are used as mediators between the keys.

1st example: From D major to A major

Here a D major cadence with the functions tonic-dominant-tonic sounds first . The dominant of D major in the second bar is reinterpreted as the tonic of A major. This key is then consolidated by the A major cadence tonic-subdominant-dominant-tonic. The movement could now be continued in A major or proceed to further modulations; here he returns to the original key after the break with the D major cadence tonic-subdominant-dominant-tonic.

This "dominant modulation" is the most common of all modulations. It is so common as a form of evasion that the dominant of the dominant is referred to as the double dominant or DD for short. This means that the functions of the chords in the example can also be described as follows:

D major: TDT | DT DD | D | TSD | T

2nd example: From F major to A minor

Here an F major chord sounds first (this key could be consolidated with a cadence TSDT, which is not shown here). The second chord df'a'd '' is the tonic parallel T p of F major, in the following it is reinterpreted as the subdominant of A minor. The D minor triad can therefore be used as a modulator between F major and A minor. The change in function of this triad only becomes plausible for the listener in retrospect, when it is followed by a cadence or at least a dominant-tonic connection in the target key of A minor.

Enharmonic modulation

In enharmonic modulation, a harmonic reinterpretation takes place in that notes of a sound are confused enharmonically , which changes the tendency of the chord to dissolve. The diminished seventh chord is often used for this, as it can be reinterpreted in many ways. The usual dominant seventh chord on the 5th scale is also often used for enharmonic modulation. B. to (tonally identical, but different from the tendency to dissolve) excessive fifth sixth chord is reinterpreted.

example

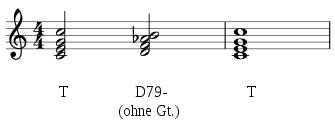

Here the enharmonic modulation is explained on the basis of the diminished seventh chord on the 7th scale or the shortened dominant seventh chord (shortened = without a chord root) with a minor ninth , the D 7 9− (the crossed out D should indicate that the root is missing). In contrast to the diatonic modulation, this chord is not reinterpreted functionally here, but always remains the dominant . However, its notes can be reinterpreted in such a way that it becomes the dominant of a different key : The dominant in C major is reinterpreted as a dominant in A major.

More detailed explanation

The starting point is an ordinary TD 7 -T connection (in steps: IVI, and specifically in our example key of C major the chords CG 7 -C :):

The dominant seventh chord (D 7 ) in the key of C major consists of:

- g - chord root g

- h - third

- d - fifth

- f - seventh

Here the D 7 is arranged as a third quarto chord for reasons of voice guidance ; So nothing changes in the tonal material of the dominant sound, it remains with the function that cannot be reinterpreted: Dominant to C. A high alteration with subsequent enharmonic reinterpretation of the fundamental g to the minor ninth a, however, turns the D 7 into a D 7 9− , which is also among the Designations Dv (v from "diminished") as well as the fully diminished seventh chord is known and has the ability to appear as the dominant of four different keys (see below). After this measure, regardless of whether you actually want to use this sound for modulation or not, you have to deal with a dominant that sounds a bit sharper, more compelling and more "dramatic" than the usual D 7 :

- Fifth d

- Seventh f

- small ninth as (instead of the chord root g)

- Third h

A dominant seventh chord D 7 tends to dissolve into the tonic. While the seventh of D 7 points towards a half-tone step down, to the third of the tonic triad (here: from f to e), the third of D 7, as a leading tone , tends to move up a half-step to the root of the key (here: from h to c). The question of why the D 7 9− sounds even more tense than the normal D 7 can be answered as follows: With the small ninth, the tritone content has risen to 2, and this tone also strives in a certain direction, namely down by a semitone on the fifth of the tonic triad (here: from a flat to g).

The reason that the D 7 9− can serve as the dominant of four different tonic triads is that the distance between any chord tone and its neighbors is always equal to a minor third.

Therefore, the chord tones can switch roles without depriving the chord of its dominant character. Each chord tone can be a minor ninth, third, fifth, or seventh. Such a role reversal also causes a change in the target key - exactly what a modulation should do.

In equal mood :

In a pure mood :

In this example, the dominant of C major, represented by D 7 9− , is reinterpreted as the dominant of A major. First of all, it consists of the tones

- Fifth d

- Seventh f

- small ninth as (instead of the chord root g)

- Third h

which do not change either. After their reinterpretation, however, they play different roles and are now sometimes referred to differently:

- Seventh d

- small ninth f (instead of the chord root e)

- Third g sharp (the former a flat)

- Fifth h

The note a / g sharp deserves special attention here: As a flat, as a small ninth above g, it showed tendencies towards resolution down to g, to the fifth of the tonic of C major. As a G sharp, as a third over E, on the other hand, it acts as a leading tone that tends towards the fundamental tone of the new tonic (A major triad).

Enarmonic modulation is a very elegant way to change the key quickly. In the following example, the key of the Christmas carol “ O you cheerful ” changes from E flat major to D major using D 7 9− . In one fell swoop, the distance of at least 5 fifths is bridged:

Here, however, the reinterpreted chord is not used as a direct dominant to the desired target key D major, but as a double dominant (i.e. as the dominant of the dominant to the actual target key D major).

Chromatic modulation

With chromatic modulation, root tones are altered in order to gradually achieve root tones of the target key. The altered tones are often leading tones . So here too:

This example shows a chromatic modulation from C major to A minor. At the beginning there is an ordinary cadence in C major (just to make it clear that we are initially in C major). After the tonic has been reached again, it appears a second time, but no longer with the fifth g, but with the fifth g sharp. This is only a small change, but with a big effect: the G sharp acts as a leading tone and strives towards the a. Nothing stands in the way of an immediate cadencing in the direction of A minor. A second cadence (blue color) consolidates and confirms the new key of A minor.

Another example should show that the chromatic modulation also works without a leading tone effect. Starting key is A minor, target key is G minor:

Here, too, a cadence ensures the starting key. Then the tonic appears twice, once normal and then with a lower fifth: it becomes e. This sound could be interpreted several times, but we take it as a subdominant with added sixth (c-es-ga, where the g is missing) and lead it to the tonic of the target key (appears with a third in the bass for reasons of voice control ). The following cadence finally leads to G minor, an additional cadence (in blue color) consolidates the new key of G minor.

Modulation by sequence

Especially in baroque pieces one finds modulations that are achieved by tonal fifth case sequences . According to the order of the keys in the circle of fifths , the characterizing accidentals of a key are changed during the sequence . Starting from the key of C major (unsigned), on the way to A major (three sharps) first the f sharp, then the c sharp, then the g sharp is added. This also happens with the key of E flat major, which uses the three bs as accidentals: First the b is added, then the es, then the a flat. If you want to modulate from a sharp key to a flat key, the sharps are gradually added first dismantled, then added the bs in the usual order. From G major to E flat major, first the f sharp would have to be made to f, then the b to b, then the e to es, then the a to a flat.

When modulating by sequence , it should be noted that especially in the minor keys, a cadence is necessary before and after the modulation process to acoustically clarify the original and target keys. In addition, modulating into more distant keys can take more time than is good for the composition. Theoretically, you can modulate through the entire circle of fifths in this way, always one key after the other, in practice this possibility is through keyboard and the like. limited.

Sound center introduction

Another particularly simple means of changing between two keys is the key-centered introduction of a new key. A note from the chord of the original key is held or continuously repeated in order to then appear as a note within a new chord. The new chord can also have a very large distance from the chord of the original key, because the previous key is temporarily canceled due to the absence of any other reference tones. Musically, one sometimes finds a ritardando in front of such passages in order to make the entry of the new key all the more clear.

After the modulation, the target key must be consolidated by a cadence with characteristic consonances and dissonances.

In this example, the note g determines what happens: In the soprano it is repeated steadily in a steady rhythm (always eighth notes), in the bass, too, only g appears, but here with a constantly repeating rhythmic motif (dotted quarter - eighth - quarter). The g in the outside voices acts like a canvas on which the harmonic events are applied. G is the "red thread" in a disjointed sequence of chords (distance G minor - E minor: 3 fifth steps; distance E minor - E flat major: 4 fifth steps; distance E flat major - C major: 3 fifth steps) .

use

Modulation is considered to be one of the most important tools in composition and an important element in musicology . However, all of the above steps only serve as material and means for the composition process, which does not necessarily have to be guided by these rules. It prepares the listener for the next part of the piece. Often the key and dynamics are already brought into the next form in order to ensure a better transition. The clearly separated combination of several types of modulation is just as possible as a gradual transition. In-depth knowledge of the modulation process is provided by studying music in the subjects of composition and harmony .

Web links

- Lehrklänge | Modulation by Markus Gorski

- Ulrich Kaiser : What is a modulation? Tutorial on musikanalyse.net

literature

- Heinz Acker: Modulation theory. Exercises - analyzes - literature examples. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2009, ISBN 9783761821268 .

- Reinhard Amon: Lexicon of harmony. Reference work on major minor harmony with analysis codes for functions, levels and jazz chords. Doblinger et al., Vienna et al. 2005, ISBN 3-900695-70-9 .

- Christoph von Blumröder : Modulatio / Modulation . In: Concise dictionary of musical terminology . Vol. 4, ed. by Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht and Albrecht Riethmüller , editor-in-chief Markus Bandur, Steiner, Stuttgart 1972–2006 ( online ).

- Michael Dachs , Paul Söhner: Harmony. Volume 1. 16th edition, revised and supplemented. Kösel, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-466-30013-4 .

- Michael Dachs, Paul Söhner: Harmony. Volume 2. 10th unchanged edition. Kösel, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-466-30014-2 .

- Doris Geller: Modulation Theory. Breitkopf and Härtel, Wiesbaden et al. 2002, ISBN 3-7651-0368-3 .

- Clemens Kühn : Modulation compact: Explore - experience - try out - invent . Bärenreiter, Kassel 2013, ISBN 978-3-7618-2334-7 .