Northern rockhopper penguin

| Northern rockhopper penguin | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Northern rockhopper penguin in the Berlin Zoological Garden |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Eudyptes moseleyi | ||||||||||||

| Mathews & Iredale , 1921 |

The northern rockhopper penguin ( Eudyptes moseleyi , English: Northern Rockhopper Penguin, Moseley's rockhopper penguin, Moseley's penguin) is a penguin species that has only been recognized as a separate species since 2006. It is very similar to the rockhopper penguin ( Eudyptes chrysocome ), but lives in a different range and shows genetic and slight physical differences.

A 2009 study revealed that the northern rockhopper penguin population has declined by 90% since the 1950s. Therefore, the IUCN has added the northern rockhopper penguin to the Red List of Endangered Species as Endangered.

Taxonomy

The rockhopper penguins were traditionally understood as a broad species with three subspecies, the southern Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome (Forster, 1781), the eastern Eudyptes chrysocome filholi Hutton, 1879 and the northern Eudyptes chrysocome moseleyi Mathews & Iredale 1921. The three subspecies were based on the The length of the tufted feathers, the extent and color of the skin of the feet, the color pattern of the lower wings and the size of the eye stripe differed. In addition, the northern rockhopper penguin is larger than the other two subspecies. In addition to morphological differences, a significantly different mating call of the northern subspecies, i.e. a behavioral characteristic, had been known since 1982.

Two genetic examinations in 2006, which examined the relationship of the subspecies on the basis of the sequence comparison of different regions of the MtDNA , showed all three or the northern versus the two southern ones as separate, respectively monophyletic units. This was confirmed in later studies. Even in the first investigation, the southern and eastern subspecies were much more closely related to each other than to the northern. The authors of the first study suggested that all three subspecies should be considered as species, while those of the second only separated the northern subspecies as a separate species. This view has become widely accepted, but is not yet recognized by all taxonomists.

As an additional argument for separation, and thus reproductive isolation , differences in their parasites could also be demonstrated. The penguins are parasitized by a total of 15 species of pine lice from two genera. In rockhopper penguins, the species Austrogoniodes keleri occurs only in the southern, Austrogoniodes concii only in the northern and Austrogoniodes hamiltoni only in the eastern populations. The lice can only be transmitted through direct physical contact.

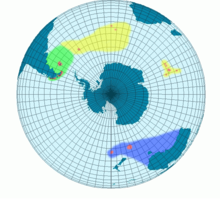

A major factor in the separation of the northern and southern rockhopper penguins could be the Antarctic convergence , a front that separates cold Antarctic (about 7 ° C) from warmer subtropical (about 12 ° C) water in a sharp gradient and which acts as an important sheath in the distribution of many marine life is proven. The northern species lives north, the southern south of this. Dating of the species splitting using the molecular clock method suggest that the two separated about 0.9 million years ago when convergence shifted south. The populations of rockhopper penguins on the northernmost islands now lived north of it, under completely different ecological conditions, and evolved separately from their southern relatives, resulting in a vicarious distribution pattern. The Amsterdam Island , which emerged from the sea much later, about 0.25 million years ago , was then populated by animals from the northern population, i.e. animals from the appropriate climatic zone, not from the much closer southern islands. In 2007, a single northern rockhopper penguin was first reported, which was found in the distribution area of the southern species, on the Kerguelen . Genetic markers suggested it came from Gough Island , 6,000 km away. This leads to the conclusion that both species are now genetically clearly separated units, since even occasional stray visitors no longer lead to genetic introgression, which would otherwise have to be clearly recognizable in the genome.

features

The Northern Rockhopper penguins reach a height of 45 to 62 centimeters. The weight varies considerably over the course of a year, generally they are heaviest shortly before moulting and can then weigh up to 3.8 kilograms. Less well fed rockhopper penguins occasionally weigh as little as two kilograms. Basically, they are among the smallest penguins ever. There is no noticeable sexual dimorphism , but females tend to be somewhat smaller. The plumage shows no seasonal variations. Young birds can be distinguished from adult rockhopper penguins up to an age of two years by their plumage.

Adult birds have a narrow yellow stripe over the eyes, the feathers of which are greatly elongated and stick out behind the eye; Further towards the back of the head, these feathers are striped lengthways with yellow and black, where they form a loosely attached tuft. The eyes are red, the short, strong and bulging beak is reddish-brown, feet and legs are pink, the soles are black. The head and face are otherwise black. The top of the body is dark slate gray. Freshly moulted plumage has a bluish shimmer. Worn plumage shortly before moulting looks brownish. The underside of the body is white and sharply set off from the black throat. The wings are transformed into fins and are blue-black on the top and white on the underside.

Young birds are smaller than adult birds. Their chin and throat are gray. The beak is smaller and more dull in color. They either do not have any elongated feathers or they are significantly shorter than those of the adult birds. The plumage of the chicks is completely black and without any markings, as is the beak. Immature animals can be recognized by a dull yellow line over the eye and a red-brown beak, but a lack of tufts.

distribution and habitat

More than 99% of the northern rockhopper penguins breed on Tristan da Cunha and the surrounding archipelago and Gough Island in the southern Atlantic Ocean . There are other breeding records for the Amsterdam and Saint Paul Islands . After the breeding and moulting season, the animals live in the open ocean for up to six months. Occasionally animals have been sighted north to South Africa.

Stranded in Australia

Far away from the natural habitat, two male individuals - stranded and injured - were found once in November 2016 on two beaches on the Australian east coast. They were cared for and came to the Schönbrunn Zoo in Vienna in October 2017 and, after quarantine, were added to the group of around 50 conspecifics in the Polarium there.

Ecology and behavior

food

The penguins are food generalists; they eat everything they can catch and consume. Investigations have shown crustaceans (e.g. Euphausia , Thysanoessa , Themisto ), squids ( Gonatus , Loligo , Onychoteuthis , Teuthowenia ) and various small fish in different proportions. Mostly they hunt in groups, rarely to depths below 100 m.

behavior

Although the animals are relatively small, they are considered to be able to defend themselves against much larger attackers. Rockhopper penguins indiscriminately attack any animal that comes near their nest, whether other penguins, albatrosses or humans. On the other hand, the animals are extremely affectionate towards their partners and social plumage care is common.

Multiplication

The birds breed on their islands in colonies in all possible areas from sea level up in cliffs and even in the interior of the islands, sometimes in stocks of the tall growing grass species Spartina arundinacea . The mating ritual also differs from the subspecies of the southern rockhopper penguin: the mating calls and the use of the feather heads differ significantly. The animals mate immediately after returning to the breeding island, in late July or August, usually with the same partner as in the previous year. Then the female scratches out a small nest hollow, for which the male provides cushioning material such as grass and feathers. The pairs defend the immediate nest area within the breeding colony as territory. The female lays two eggs, the first of which is always noticeably smaller than the second. The first egg is usually lost and is only seldom incubated, even if two cubs hatch, as a rule only the larger one survives. There are seldom nests with three eggs, whether this is due to additionally laid or smuggled in by foreign females is unknown. The breeding season lasts about 32 to 34 days, with both parents incubating alternately. After hatching, initially only the female feeds, later both parents. The young become adults with the moult, after about 9 to 10 weeks, independently. The adult animals feed their young with smaller pieces of prey than what they would prey for themselves. During the breeding season, the animals first feed on krill and then add fish to their diet.

Enemies

Adult animals have no natural enemies on land, but in the sea they are prey to orcas and sea lions. Eggs and chicks are eaten by skuas , gulls and vulture falcons . On some islands, enemies (cats, rats) have also been introduced by human hands.

Population and threat

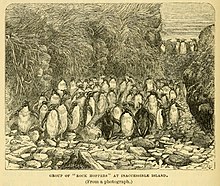

The current population is estimated at 100,000–499,999 breeding pairs on Gough Island, 18,000–27,000 pairs on Inaccessible Island, and 3,200–4,500 on Tristan da Cunha. The decrease in the number of individuals is approx. 2.7% annually; The loss on Gough Island has been calculated at a loss of 100 animals per day since the 1950's.

This means that the population has declined by 90% since the 1950s, possibly due to climate change , changes in the ecosystem, and human overfishing of squid. additional factors are pollution and disturbances from ecotourism and fisheries, as well as egg collectors and hunting and food competition from sub-Antarctic fur seals ( Arctocephalus tropicalis ). Also house mice ( Mus musculus ) were brought by humans to the islands. The mice are an invasive species and, among other things, feed on the eggs of penguins and also prey on chicks. Therefore, catching actions for mice were planned.

Due to the population decline, the northern rockhopper penguin is classified as "endangered".

Population developments by year and island

| island | year | estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Gough | 1889 | "Millions" |

| 1956 | ~ 2 million | |

| 1979 | 78,300 | |

| 1984 | 142,800 | |

| 2004 | 32,400 | |

| 2006 | 64,700 | |

| Tristan | 1824 | > 200,000 |

| 1873 | > 200,000 | |

| 1923 | > 12,600 | |

| 1955 | 5,000 | |

| 1973 | 7,000 | |

| 1984 | 4,300 | |

| 1992 | 3,343 | |

| 2005 | 3,421 | |

| Inaccessible | 1955 | > 25,000 |

| 1989 | 22,000 | |

| 1999 | 27,000 | |

| 2004 | 18,000 | |

| Nightingale | 1973 | 25,000 |

| 2005 | 19,500 | |

| Middle | 1973 | 100,000 |

2011 tank accident

On March 16, 2011, the freighter MS Oliva , which ran under the Maltese flag, ran aground off Nightingale Island , with many tons of heavy fuel oil spilling. The crew was rescued, but the ship broke up and the island was surrounded by a film of oil that threatened the penguin population. Fresh water is not available on Nightingale Island. Therefore, the penguins were brought to Tristan da Cunha to purify them.

In pop culture

- Cody Maverick , a seventeen-year-old penguin, stars in the 2007 films Kings of the Waves and 2017 Kings of the Waves 2-Wave Mania.

- Secret Agent Buck Rockgut , is one of the penguins from Madagascar .

- In Happy Feet and Happy Feet 2 , Lovelace, a Barry White -like love guru, is a rockhopper penguin who reveals his wisdom in return for rock compensation. Lovelace is originally voiced by Robin Williams .

- One of the penguins of the Penguin Palooza mascots of the Newport Aquarium in Kentucky , United States , "Rocky", is a Northern rockhopper penguin.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Eudyptes moseleyi in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2016 Posted by: BirdLife International, 2016. Accessed February 1, 2017th

- ^ Higgins PJ Marchant S: Handbook of Australian, New Zealand, and Antarctic Birds. . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1990.

- ↑ Pierre Jouventin: Visual and Vocal Signals in Penguins, their Evolution and Adaptive Characters. (Advances in Ethology 24) Paul Parey, Berlin and Hamburg 1982.

- ^ J. Banks, A. Van Buren, Y. Cherel, JB Whitfield: Genetic evidence for three species of Rockhopper Penguins, "Eudyptes chrysocome" . Polar Biology 2006, 30: 61-67. doi: 10.1007 / s00300-006-0160-3

- ↑ a b c P. Jouventin, RJ Cuthbert, R. Ottvall: Genetic isolation and divergence in sexual traits: evidence for the Northern Rockhopper Penguin "Eudyptes moseleyi" being a sibling species . Molecular Ecology 2006, 15: 3413-3423. doi: 10.1111 / j.1365-294X.2006.03028.x

- ^ RD Price, RA Hellenthal, RL Palma: World Checklist of Chewing Lice with Host Associations and Keys to Families and Genera. In RD Price, RA Hellenthal, RL Palma, KP Johnson, DH Clayton (editors): The chewing lice. World checklist and biological overview. Illinois Natural History Survey Special Publication, 24. Champaign, IL 2003: 1-448.

- ↑ Louse-host associations | Phthiraptera.info . Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- ^ Marshall group: The Ecology of Ectoparasitic Insects . Academic, London 1981.

- ↑ M. de Dinechin, R. Ottvall, P. Quillfeldt, P. Jouventin: Speciation chronology of northern rockhopper penguins inferred from molecular, geological and palaeoceanographic data . Journal of Biogeography 2009, 36 (4): 693-702. doi: 10.1111 / j.1365-2699.2008.02014.x

- ↑ M. de Dinechin, G. Pincemy, P. Jouventin: A northern rockhopper penguin unveils dispersion pathways in the Southern Ocean . In: Polar Biology 2007, 31 (1): 113-115 doi: 10.1007 / s00300-007-0350-7

- ^ Williams, p. 187

- ^ Williams, p. 185

- ↑ a b c d e f BirdLife International (2008). Species factsheet: Eudyptes moseleyi . Retrieved January 16, 2009.

- ^ A b c Richard J. Cuthbert: Northern Rockhopper Penguin. In: Pablo Garcia Borboroglu, P. Dee Boersma: Penguins: Natural History and Conservation. University of Washington Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-295-99906-7 .

- ↑ New beginning for stray penguins in Schönbrunn orf.at, December 14, 2017, accessed December 14, 2017.

- ↑ Cindy L. Hull, Mark Hindell, Kirsten Le Mar, Paul Scofield, Jane Wilson, Mary-Anne Lea: The breeding biology and factors affecting reproductive success in rockhopper penguins Eudyptes chrysocome at Macquarie Island . In: Polar Biology . 27, No. 11, July 22, 2004, ISSN 0722-4060 , pp. 711-720. doi : 10.1007 / s00300-004-0643-z .

- ↑ P. Jouventin, RJ Cuthbert, R. Ottvall: Genetic isolation and divergence in sexual traits: evidence for the northern rockhopper penguin Eudyptes moseleyi being a sibling species . In: Molecular Ecology . 15, No. 11, October 1, 2006, ISSN 0962-1083 , pp. 3413-3423. doi : 10.1111 / j.1365-294X.2006.03028.x . PMID 16968279 .

- ↑ Higher trophic level price does not represent a higher quality diet in a threatened seabird: implications for relating population dynamics to diet shifts inferred from stable isotopes . Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ↑ msnbc.com. Northern rockhopper penguins near extinction . January 16, 2009.

- ^ BirdLife International. Penguins are walking an increasingly rocky road . January 16, 2009.

- ↑ RM Wanless, N. Ratcliffe, A. Angel, BC Bowie, K. Cita, GM Hilton, P. Kritzinger, PG Ryan, M. Slabber: Predation of Atlantic Petrel chicks by house mice on Gough Island . In: Animal Conservation . 15, No. 5, October 1, 2012, ISSN 1469-1795 , pp. 472-479. doi : 10.1111 / j.1469-1795.2012.00534.x .

- ↑ MS Oliva runs aground on Nightingale Island . The Tristan da Cunha website. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ Oil Spill Menaces Penguins . In: Science . 331, March 25, 2011, p. 1499. doi : 10.1126 / science.331.6024.1499-b .

- ↑ BBC News Oil-soaked rockhopper penguins in rehabilitation

- ↑ Surf's Up at IMDb

- ↑ Happy Feet at IMDb . IMDb. Retrieved October 26, 2015.