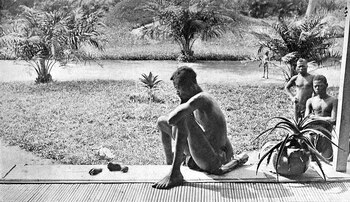

Nsala of Wala in the Nsongo District (Abir Concession)

Under the title nsala of Wala in the Nsongo District (Abir Concession) (English for "nsala of Wala in district Nsongo ( Abir -Konzessionsgebiet)") was published in 1904 in the work of King Leopold's Rule in Africa by Edmund Dene Morel , a photo , the Congolese one named Nsala when looking at a severed foot and a severed hand of his five-year-old daughter Boali. The photo was taken by Alice Seeley Harris , the wife of a missionary, in the town of Baringa on May 14, 1904. The photo was a means of the media fight against the inhumane situation in the Congo Free State, which was largely characterized by rubber exploitation .

It is part of the Harris Papers , a collection owned by Anti-Slavery International .

description

The picture shows a man wearing only a loincloth sitting in the center of the picture on the edge of a veranda , photographed from the veranda. His gaze is directed in front of him, to the lower left of the picture, at the severed hand and foot of a child lying on the veranda. In the right half of the picture, further back in the picture, standing in front of the veranda, two other equally clothed male people can be seen with their gaze directed towards the viewer of the picture. A fourth person stands in the background of the picture, also in the right half of the picture (the picture was printed in different excerpts and partly mirror-inverted, the position and direction information refer to the print by Morel).

Historical background

In 1885, as a result of the Congo Conference, the Congo Free State was de facto assigned to the Belgian King Leopold II as personal property. During the Free State era, the population was systematically forced to harvest rubber . Enforcement resulted in numerous ill-treatment and numerous deaths. At the end of the 19th century there was a strong demand for rubber , so that this form of exploitation was very lucrative for Leopold; the consequences were initially negated or even concealed.

On the basis of assessments by witnesses and later censuses, estimates of the number of fatalities from colonial policy in the time of the Congo Free State come about, which start at around 2.2 million. Higher estimates put a population decline of up to 21.5 million. In 1998, Adam Hochschild believed that around 10 million deaths were realistic.

The coercive measures were again enforced by the Force Publique , the army of the Free State, and by private guards from the rubber companies involved, such as the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company (ABIR) . Workers recruited both in the area of the Free State and from other African areas were deployed.

From 1877 missionary activities began with the first Baptist missionaries from Great Britain in the area that would later become the Free State . Later American and Belgian groups of different denominations were added. In the self-portrayal of Leopold and missionaries, colonialism in the Congo serves a “civilization” and is largely driven by conversion to Christianity. It was emphasized that this was linked to the fight against slave trade , cannibalism and polygamy .

At the beginning of the 20th century, reports about the conditions in the Congo Free State increasingly came into the consciousness of the western world public, which led to public criticism of Leopold's politics. The Congo Reform Association, co-founded by Edmund Dene Morel , is seen as particularly influential . Missionaries and missionary societies also publicly criticized and delivered reports from the Congo Free State. The technology of photography also played a role, which had an impact on the public through newspapers and magazines as well as at lantern shows , favored by the then relatively new possibilities of mass reproduction of photos via print grids and the development towards faster, lighter, smaller and less expensive Cameras. An attempt was made to counteract the criticism through lobbying and public relations work and the appointment of an investigative commission by Leopold. In 1908 Leopold sold the Congo Free State to the Belgian state.

The ABIR had a concession to exploit all raw materials of the forest in the area of the Lopori-Maringa basin . Baringa, the location where the photo was taken, is on Maringa, southeast of the city of Basankusu , where Maringa and Lopori merge and ABIR has had its headquarters since 1893. Since the company was restructured in 1898, half of ABIR has belonged to the Congo Free State, with other larger shareholders being a Belgian banker and Société Anversoise , another rubber company in the Congo. The rubber was obtained in the ABIR region as the juice of certain tendrils, mostly of the subspecies landolphia owariensis gentilii . Repeated cutting for this purpose dried out the tendrils and sometimes died. The rubber sufferers also died if they were completely severed for tapping. In 1904, the year the photo was taken, it was reported that rubber was almost completely exhausted within 50 miles of most of the ABIR posts; the amount of rubber exported by ABIR fell from 1903 to 1904 by about half.

Before the beginning of the rubber exploitation, most of the residents of the Lopori-Maringa Basin were farming, alongside there were also fishermen and hunters. Even before the time of the Congo Free State, there had been armed conflict in the region through the nineteenth century, which was accompanied by enslavement . In the 1880s it was repeatedly raided by traders from Irebu for slaves and ivory .

The ABIR had posts across the area responsible for one region each, for each of which one or two European employees were responsible, who received commissions on the rubber delivered and whose salary was reduced if a quota was not met. Based on the number of men in a village, the guards in turn imposed rubber quotas on the individual villages, which the ABIR guards were responsible for collecting. If the quotas were not met, they faced wage cuts, layoffs, imprisonment or flogging. While a smaller number of the guards ("post sentries") were equipped with comparatively modern Albini Braendlin rifles , the guards stationed in the villages ("village sentries") used muzzle-loaders . The guards were sometimes required to show a right hand for each cartridge used as proof of their work. The ABIR was able to fall back on the support of the state army, which sent troops stationed in Basankusu in the event of strong resistance in the population to suppress it, and was also supported logistically and with weapons licenses.

The men forced to collect were paid for the rubber. The company had prisons where men who didn't meet their quotas were detained and forced to work. Instead, wives or other close relatives were often held hostage, which had the advantage that the affected man could continue to collect rubber. If villages did not meet their quota, the respective chiefs were often taken hostage.

The village of Wala belonged to Nsongo Mboyo, a group of villages in the ABIR concession area, now groupement , which, according to data from the state Réferentiel Geographique Commun (RGC), is east of Baringa north of the Maringa. In 1903, over 1,000 of the Nsongo Mboyo people who tried to escape the concession area were taken to Lireko labor camp. In May 1904, 83 people are said to have been murdered by the ABIR guards in Wala alone.

Assessment of the missionaries from Baringa on the local situation

John Harris, Alice Harris' husband , testified to the investigative commission established by Leopold in 1904 into crimes in the Congo: “ […] so far as we are aware, no single sentry had ever been punished by the State till 1904 for the many murders committed in this district ”(German:“ […] as far as we are aware, not a single guard [of the ABIR] was ever convicted by the state for the many murders that were committed in this district until 1904 ”). Edgar Stannard, a medical missionary in Baringa, told the commission that the ABIR guards had used Albini rifles, which they were legally prohibited from wielding, to quell unrest in Nsongo. Harris and Stannard also reported ABIR administrators whipping guards when they hadn't killed enough people. According to John Harris in 1905, the guards in Nsongo District were known for cannibalism. Edgar Stannard gives statements from residents of Nsongo that guards originally from the area were deployed, but were relieved of their duties and disarmed by “ the white man ” because they were not “ their own” people ”(German:“ their own people ”), whereupon they were replaced by guards from areas known for cannibalism. Robert M. Burroughs sees in Harris' characterization of guards as " ignorant, uncivilized and to a large extent cannibal " (German: "uneducated, uncivilized and largely cannibal") an example of how a comparatively progressive person under certain circumstances Circumstances fall back on idioms of the defenders of the Free State, and problematizes the stories of the missionaries of statements of local people as an expression of the position of the missionaries against the background of their opposition to many expressions of cultural autonomy.

The missionaries' account of the creation of the picture

Events that form the background of the picture are described in letters from the Harrises and Stannards: Alice Harris wrote on May 15, 1904, to Raoul Van Calcken, the head of the ABIR post at Baringa. Baringa missionaries John Harris and Edgar Stannard wrote to the founder and then leader of the Baptist Congo-Balolo Mission that paid for the Harrises and co-founder of the Congo Reform Association Henry Grattan Guinness on May 19 and 21, respectively. If you follow Stannard's letter, the following sequence of events results:

On May 14, 1904, the day of the admission, John Harris had left for a meeting in Jikau . Shortly after eight in the morning, when Alice Harris and Edgar Stannard were at Harris's house, two boys on the mission reported that guards had killed several people and that two men were out and could show their hands as evidence. The boys were asked to alert Harris and Stannard when the men returned. Shortly afterwards, the men came to Harris and Stannard and were asked to show their hands. They showed a hand and foot that Stannard reckoned fresh and that could have belonged to a child five years old or less. One of the two men, Nsala from Wala, introduced himself as the father of the killed Boali, who had heard the limbs. They reported that fifteen guards had come to Wala the day before to collect rubber, although the delivery date was not scheduled for three days. Two of them carried Albini rifles. In addition to Boali, Nsala's wife Bonginganoa and a boy named Esanga were shot and then cut up and cooked. Three other people were gunshot wounds, one of whom, Eikitunga, fell into a river and drowned while trying to escape. In addition, the guards took ten prisoners, nine of them women who, according to Stannard's account, were not responsible for collecting rubber because of their gender, confirmed by a judge named Bosco. Eight of the women were then released against payment.

According to himself, Nsala had secretly picked up his daughter's hand and foot in order to be able to use them as evidence. When asked whether he had cut it off himself, he denied this. Finally Alice Harris took the picture on the porch of the house. She used one of their photos dry plate camera company Kodak . Edgar Stannard described Nsala as “ dazed with grief ” (German: “dazed by grief”), “ horror-stricken ” (German: “struck by gray”) and “ sorrowing ” (German: “suffering”).

Historian Kevin Grant suspects that Alice Harris resorted to an interpreter during the conversations due to the insignificance of her knowledge of the Lomongo used in the region .

Before meeting Harris and Stannard, the men had already met Raoul Van Calcken from ABIR. After Harris and Stannard pointed out the incident, he claimed, contrary to the testimony of the two men from Wala, that he had not been shown the hand and foot. Two days later, Bompenju and Lofiko, Nsalas brothers, went to the mission and confirmed what had happened in Wala. On that occasion, Botondo, who works for the mission, reported seeing Van Calcken's hand and foot shown. House worker Bokalo said that the two men, with their hand and foot, before meeting Harris and Stannard, when asked to show their limbs to the mission, expressed fear because, according to their testimony of the " rubber white man " ( Rubber whites ) were asked not to do so. Harris and Stannard were also told that a person whose name was deleted from Morel's edition of Stannard's letter asked guards to kill some people. After learning that the British missionaries knew of killings, he told the guards not to kill any more people. Other people told Stannard the following day that some women detained had been held outside ABIR prison to prevent British missionaries from finding out about the arrests of women.

From May 24th to 26th, Stannard visited Wala. He learned that one of the wounded had since died, examined the body and attested a gunshot wound. Even with the injured chief Elisi, whom he treated the next day, he found that the wounds must have come from a bullet. Elisi said that the Lifinda / Lifunda guards first took some prisoners when they arrived. When he asked their leader Lifumba, pointing out that the rubber delivery was only due in three days, for the reason, he was shot at by him with an Albini rifle. Others, including chief Mpombo, said that the killings and feasting had taken place afterwards, Boali was shot by Likilo, Bondingangoa by Mboyo and Esanga by Lomboto.

The guards also reportedly stayed one night in Wala and returned to Lifinda the next morning. On the way back, when asked for a reason again, referring to the delivery date, the guard shot Bokumgu Isekolumbo. At Stannard's request, he was also shown alleged pieces of bones from people who had been eaten: One piece is said to have belonged to Boalis's forearm, another to the leg of a woman named Balengola.

According to Stannard, John Harris and Edgar Stannard reported the events to Judge Bosco, who had been asked in writing to visit, on June 4th, and Stannard signed a statement on some aspects.

More photography five days later

Edgar Stannard also reports in his correspondence about another testimony of the Nsalas brothers and another photograph: After John Harris returned on May 19, Bompenju and Lofiko visited the mission again the following day with a third man and reported three other dead. One had been eaten, and the other two, Bolengo and Lingomo, showed their hands. Alice Harris took a photo of the three men with hands, John Harris and Edgar Stannards. John Harris and the men went to Van Calcken. Alice Harris and Edgar Stannard spoke to other residents of Wala, who said that the killings had taken place three days earlier and that it was a woman, a man and a boy.

Use of the image

In his letter to Guinness, dated five days after the picture, John Harris wrote of this:

"The photograph is most telling, and as a slide will rouse any audience to an outburst of rage, the expression on the father's face the horror of the by-standers the mute appeal of the hand and foot will speak to the most skeptical."

“The photography is extremely telling and will enrage any audience if you watch a slide show; the expression on the father's face, the horror of those standing by, the silent complaint of the hand and foot will appeal to even the most skeptical. "

Furthermore, he wrote, “ [it] might be useful to the government ” (German: “it could be useful to the government”).

Alice Harris sent the photo to the Marquess of Bath , an acquaintance of her father. British parliamentarians from the father's circle of friends also received the photo.

The picture appeared in newspapers and other periodicals . After their return to Great Britain in July 1905, the Harrises presented their slides both in Europe and in North America, among other things in a compilation Lantern lecture on the Congo atrocities , which contains the picture under the title Nsala with his child's hand and foot . According to T. Jack Thompson from the theological faculty of the University of Edinburgh , however, due to the loss of the slides, it can no longer be determined whether Guinness also used the photo in his presentations.

Edmund Dene Morel took the picture and attached Stannard's letter to Guinness describing how it came about in his work King Leopold's Rule in Africa from 1904.

In Mark Twain's work King Leopold's Soliloquy ( English King Leopold's Soliloquy ) , an ironically written from the perspective of Leopold the Free State to critical polemic of 1905, the picture was also printed with the following caption:

“Foot and hand of child dismembered by soldiers, brought to missionaries by dazed father. From photograph taken at Baringa, Congo State, May 15, 1904. See Memorial to Congress, January, 1905 ”

“Foot and hand of a child dismembered by soldiers, brought to missionaries by a dazed father. From a photograph taken in Baringa, Congo State, May 15, 1904. See Memorial to Congress , January 1905 "

To point to a Memorial to Congress , a speech to the US Congress in January 1905. The picture also illustrates the successful book shadow over the Congo ( English King Leopold's Ghost ) by journalist Adam Hochschild from the year 1998 on the Free State.

In October 1905, Alice Harris signed a statement that she took her pictures in good faith as they were authentic after allegations of forgery were brought against pictures created by missionaries. Contemporaries also criticized the images as ideologically motivated by the Harrises' Protestantism.

Modern assessments of the picture

According to Robert M. Burroughs' assessment, the picture emphasizes an active use of the victim Nsala as a witness instead of a performance by the photographer. According to T. Jack Thompsons, the images of the Harrises differed from earlier photographs of missionaries, whose main concern was the " European civilization " (German: "European civilization") of the " African savagery " (German: "African savagery") to contrast the “ Christian light ” (German: “Christian light”) with the “ heathen darkness ” (German: “Heidnischen Finsternis”).

Sharon Sliwinski from the Faculty of Information and Media at the University of Western Ontario described the picture as “ formally posed, almost peaceful ” and further:

“Painful scrutiny is required to make out the items in front of Nsala. The object closest to him appears to be his daughter's foot, lying on its side, severed end tipped towards the camera; the object furthest is Boali's little hand, resting palm side down. These tiny body parts explode the peaceful composition of the image and illustrate an uncanny inversion of the typical representation of the injury: rather than picture a child with missing limbs, here Nsala poses with the remains of his missing child. Missing is not really the right word - Boali is more than simply absent from the scene - but perhaps there are no words which could appropriately describe the devastating affect of her nonexistent presence. "

“A painful examination is necessary to identify the objects in front of Nsala. The object closest to him seems to be his daughter's foot, lying on its side with the cut end tilted towards the camera; the farthest object is Boali's little hand, palm down. These small body parts blow up the peaceful composition of the picture and illustrate an eerie inversion of the typical depiction of an injury: instead of depicting a picture of a child with missing limbs, Nsala poses with the remains of his missing child. 'Missing' is not really the right word - Boali is more than simply absent from the scenery - but perhaps there are no words that adequately describe the devastating effect of her non-presence. "

Wayne Morrison of Queen Mary University's law school described the picture as “ [o] ne of the most dramatic ” (German: “one of the most dramatic”) of the images that made it abroad from the Free State. Robert M. Burroughs rated the picture as Alice Harris' " most famous photograph " (German: "most famous photography"). T. Jack Thompson described the picture as “ haunting ” (German: “hauntingly, deeply moving”).

literature

To the picture

-

Edmund Dene Morel : King Leopold's Rule in Africa . W. Heinemann, London 1904 ( openlibrary.org ).

- Attachment: Letter from Mr. E. Stannard . To Dr. Guinness. May 21, 1904, p. 446 ( archive.org ).

- Kevin Grant: Christian critics of empire: Missionaries, lantern lectures, and the Congo reform campaign in Britain . In: The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History . tape 29 , no. 2 . Taylor & Francis, 2001, p. 27-58 , doi : 10.1080 / 03086530108583118 .

- Wayne Morrison: A reflected gaze of humanity . Cultural criminology and images of genocide. In: Keith J. Hayward, Mike Presdee (Eds.): Framing Crime. Cultural criminology and the image . Routledge, 2010, ISBN 0-203-88075-7 , pp. 200 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- Sharon Sliwinski: The Childhood of Human Rights: The Kodak on the Congo . In: Journal of Visual Culture . tape 5 , no. 3 . SAGE Publications, 2006, pp. 333–363 , doi : 10.1177 / 1470412906070514 ( jkdweb.biz [PDF; 2.6 MB ] with a foreword by Mark Sealy).

- T. Jack Thompson: Capturing the Image: African Missionary Photography as Enslavement and Liberation . 2007 ( library.yale.edu [PDF; 2.2 MB ]).

- Daniel Vangroenweghe: Rood rubber . Leopold II in the Congo. Van Halewyck, Leuven 2010, ISBN 978-90-5617-973-1 , p. 119-121 .

Further sources for backgrounds

- Robert M. Burroughs: Travel Writing and Atrocities . Eyewitness Accounts of Colonialism in the Congo, Angola, and the Putumayo. Routledge, New York 2011, ISBN 0-203-84916-7 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- Congo Reform Association (Ed.): Evidence Laid Before The Congo Commission Of Inquiry At Bwembu, Bolobo, Lulanga, Baringa, Bongadanga, Ikau, Bonginda, and Monsembe . Together with a summary of events (and documents connected therewith) on the ABIR Concession since the Commission visited the territory. 1905 ( openlibrary.org ).

- Robert Harms: The End of Red Rubber: A Reassessment . In: Journal of African History . tape 15 , no. 1 . Cambridge University Press, 1975, pp. 73-88 , JSTOR : 181099 .

- Robert Harms: The World Abir Made: The Maringa-Lopori Basin, 1885–1903 . No. 12 , 1983, p. 125-139 , JSTOR : 3601320 .

- Robert Harms: King Leopold's Bonds . The Financial Innovations that Created Modern Capital Markets. In: William N. Goetzmann, K. Geert Rouwenhorst (Eds.): The Origin of Value . Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-19-517571-9 , pp. 343–357 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Adam Hochschild: Shadows over the Congo . The story of a great, almost forgotten crime against humanity. 3. Edition. Klett-Cotta, 2000, ISBN 3-608-91973-2 (Original title: King Leopold's Ghost - A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa .).

- T. Jack Thompson: Light on Darkness? Missionary Photography of Africa in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2012, ISBN 978-0-8028-6524-3 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Morel 1904 , p. 145.

- ↑ a b c d Grant , p. 27.

- ↑ Thompson 2007 , p. 25.

- ↑ a b Hochschild , p. 483 (original: p. 362).

- ^ Matthew White: Source List and Detailed Death Tolls for the Primary Megadeaths of the Twentieth Century. February 2011, accessed November 15, 2013 .

- ↑ Hochschild , pp. 330–331.

- ^ Edouard Descamps : New Africa . An essay on government civilization in new countries and on the Foundation, Organization and Administration of the Congo Free State. St. Dustan's House, London 1903, p. 334-336 ( archive.org ).

- ^ Sliwinski , pp. 2, 8.

- ^ Ludovic de Moncheur : Conditions in the Congo Free State . In: The North American Review . tape 179 , no. 575 . University of Northern Iowa , Oct 1904, pp. 494 , JSTOR : 25105298 .

- ^ Henry Grattan Guinness: Congo Slavery . A brief survey of the Congo Question from the humanitarian point of view. R. B. M. U. Publication Department, London, pp. 29-31 .

- ↑ Hochschild , p. 152 (original: p. 106).

- ↑ a b Thompson 2007 , p. 3.

- ↑ a b c d Burroughs , p. 87.

- ↑ Ruth Kinet: "Light in the Darkness" . Colonization and Mission in the Congo, 1876–1908 - Colonial State and National Mission between Cooperation and Confrontation. Lit Verlag , 2003, ISBN 3-8258-7574-1 , p. 74 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ a b c d Harms , p. 349.

- ↑ a b Harms 1975 , p. 81.

- ↑ Harms 2005 , pp. 351-352.

- ↑ Harms 1983 , p. 125.

- ↑ Harms 1975 , p. 79.

- ↑ a b Harms 1983 , pp. 132-133.

- ↑ Harms 2005 , p. 350.

- ^ Arthur Conan Doyle : The Crime of the Congo . 4th edition. Hutchinson & Co, London 1909, pp. 49 ( kongo-kinshasa.de (PDF; 584 kB)).

- ↑ a b Harms 1983 , p. 134.

- ^ Nancy Rose Hunt: An Acoustic Register. Rape and Repetition in Congo . In: Ann Laura Stoler (Ed.): Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination . Duke University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8223-5348-5 , pp. 55, 65 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Données administratives ( Memento from December 22, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Harms 1983 , p. 136.

- ↑ Ben Kiernan: From Irish Famine to Congo Reform . Nineteenth-Century Roots of International Human Rights Law and Activism. In: René Provost, Payam Akhavan (Ed.): Confronting Genocide . Springer , Dordrecht 2001, ISBN 978-90-481-9840-5 , p. 40 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-90-481-9840-5 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ Congo Reform Association , p. 22.

- ↑ Burroughs , p. 84.

- ^ Congo Reform Association , p. 25.

- ^ Congo Reform Association , p. 23 and p. 29.

- ^ Congo Reform Association , p. 72.

- ↑ a b Letter from Mr. E. Stannard , p. 446.

- ↑ Burroughs , p. 82.

- ↑ Burroughs , p. 93.

- ↑ Hochschild , p. 357 (original: p. 253).

- ↑ Vangroeweghe , p. 101.

- ↑ a b Thompson 2012 , p. 231.

- ^ Joseph F. Conley: Drumbeats that Changed the World . A History of the Regions Beyond Missionary Union and the West Indies Mission, 1873-1999. William Carey Library, 2000, ISBN 0-87808-603-X , pp. 69 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ a b Grant , p. 53.

- ↑ a b c d Letter from Mr. E. Stannard , p. 444.

- ↑ a b Letter from Mr. E. Stannard , p. 445.

- ↑ Sliwinski , p. 340.

- ↑ a b Letter from Mr. E. Stannard , p. 447.

- ^ Letter from Mr. E. Stannard , p. 448.

- ↑ a b Letter from Mr. E. Stannard , p. 449.

- ^ Letter from Mr. E. Stannard , p. 451.

- ↑ Vangroenweghe , p. 121.

- ↑ Thompson 2012 , pp. 230-231.

- ^ T. Jack Thompson: Light on the dark continent: the photography of Alice Seely Harris and the Congo atrocities of the early twentieth century . In: International Bulletin of Missionary Research . October 2002 ( thefreelibrary.com ).

- ^ Brian Stanley: In Memory of Dr T. Jack Thompson. ( Memento from October 22, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) In: Ed.ac.uk , August 14, 2017 (English).

- ↑ a b Thompson 2012 , p. 230.

- ^ Letter from Mr. E. Stannard , p. 442.

- ↑ Mark Twain : King Leopold's Soliloquy . A Defense of His Congo Rule. The PR Warren Co., 1905, pp. 18 ( archive.org ).

- ↑ On January 16, 1905, a memorial from an association of American mission societies on the situation in the Congo comes from , in which Stannard's letter to Guinness appeared, describing the creation of the photo, see Edmund Dene Morel : Red Rubber . The story of the Rubber Slave Trade which flourished in the Congo for twenty years, 1890-1910. National Labor Press, Manchester 1919, pp. 68 ( archive.org ). Also: United States Senate (ed.): Conditions in the Congo State . January 17, 1905, p. 17th ff . (58th Congress, 3rd Session, Document No. 102, “Referred to the Committee on Foreign Relations and ordered to be printed”).

- ↑ Burroughs , p. 88.

- ↑ a b Morrison , p. 200.

- ↑ Burroughs , p. 90.

- ↑ Sharon Sliwinski Associate Professor ( Memento December 14, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Sliwinski , pp. 341-342.

- ^ Publications: Wayne Morrison. Queen Mary University , accessed December 22, 2013 .