Peter Andreas Munch

Peter Andreas Munch (born December 15, 1810 in Christiania , † May 25, 1863 in Rome ) was a Norwegian historian. He was an uncle of the painter Edvard Munch .

Life

Munch's parents were the provost Edvard Storm Munch (1780-1847) and Johanne Sophie Hofgaard (1791-1860). He grew up in Gjerpen (district of Skien ), where his father had become a pastor in 1813. He received his first lessons with other children from his father. In addition to his school work, he read books from his father's library. These included the Heimskringla in the Norrøner language , an Icelandic grammar and an Icelandic dictionary. With these books he taught himself the norrøne language early on. In 1823 he started second grade at the Latin school in Skien. There he had the later politician Anton Martin Schweigaard as a classmate. In 1828 he began studying. In 1834 he completed his legal studies, which he had started with a view to his historical interests.

He had an unusual memory, knew several books of Livy and Homer's hymns by heart, was musically gifted and spoke several languages: Norrøn, Anglo-Saxon, English, Spanish, Portuguese and Italian.

The Storting (parliament) had approved funds for the publication of the old Norwegian laws, and he took on this task together with Rudolf Keyser .

On April 20, 1835 he married Nathalie Charlotte Linaae (* February 5, 1812 - January 18, 1900), daughter of the manager Hans Henrik Linaae (1783-1842) and his wife Karen (“Kaja”) Fredrikke Baggesen.

In the same year he traveled with Keyser to Copenhagen for two years to copy manuscripts of the law. He then traveled to Lund and Stockholm for the same purpose. When Professor Steenbloch died in Christiania, Munch applied to be a lecturer in history at the university there and was appointed in 1837. October 16, 1841 he became a professor at the Philosophical Faculty. He was elected "Assessor" of the college of professors and held this office from 1842–1843 and 1849–1850, which involved a lot of administrative work and college meetings. Together with Keyser, he was also on the faculty committee that worked out the requirements for the final philological examination after the university reform of 1845. Old Norse was introduced as an optional subject as an alternative to Hebrew. He was also the examiner in the “examen artium” for many years.

His tireless work in the collection and printing of sources, which occupied him for months into the night, drained his strength and burned him out. 1845-1854 he made many trips abroad, including 1846 to Normandy, 1849 to Scotland, the Orkneys and the Hebrides, spent three months in Edinburgh and a few weeks in London, where he wrote off important diplomas and manuscripts. In 1857 he received from Storting a grant of 480 crowns a month for two years for his archival studies abroad. He traveled to Copenhagen and Vienna. In 1858 he came to Rome. The Storting extended the fellowship, and from 1859–1861 he worked in the papal archives in Rome. His meticulously precise copies were sent in parcels to the Friends of Det lærde Holland and from there came via Ludvig Daae to the Imperial Archives in Christiania and were included in the later volumes of the Diplomatarium. To oversee this work, he traveled home in 1861 and was appointed Reich archivist. But he left his family in Rome. For two years he worked tirelessly in Christiania on the publication of the sources. In between there was an investigation in Stockholm. He was now working on the "Union Period". In May 1863 he traveled to Rome again to meet his family. There he caught a cold, but initially recovered. Then he suffered a stroke at his desk, pen in hand.

His grave is in the evangelical cemetery in Rome at the foot of the cestus pyramid. In 1856 a memorial stone was unveiled on the grave, with Henrik Ibsen giving a speech. A statue of Munch by Stinius Fredriksen was erected on University Square in Oslo in 1933. The building of the University of Oslo, which houses the historical institute, is called "PA Munchs hus".

Research and Teaching

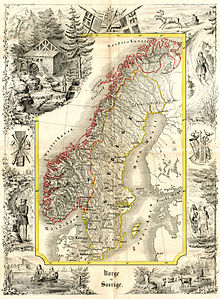

In the 1930s there was a change in cultural studies. The requirements for method and specialist knowledge increased. But the researchers were still generalists. Munch conducted research in the fields of history, linguistics, runology, myth research and geography. For the cartographic work he traveled in the summers of 1842, 1843 and 1846 through Norway to Telemarken , Numedal , Hallingdal , Hardanger and Voss . Only in the next generation, mostly students of Munch, did specialists develop for the individual areas. History remained the central area of research for him, collecting the results of the other disciplines, including fairy tales and folk tunes.

As a professor at the Philosophical Faculty, he held general lectures on general and European history as part of the compulsory study program. In 1845 there were a number of reforms in teaching. The subjects in the Studium Generale changed. History and Classical Philology were eliminated. This gave him the opportunity to concentrate more on his own interests in the lecture topics. He was now giving lectures on Norwegian history, which were also heard by Princes Gustaf and Oscar Frederik. His postponed lecture papers are characterized by a high level of care and accuracy.

Critical Research

His work was tied to the extensive research and development of a national culture that shaped his entire time and that also embraced many others, such as Ivar Åsen, Magnus Brostrup Landstad , Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe . Like all of his time, he was very committed to developing the life of the nation, and this was also the central concern of his research: the aim was to gain a richer and more reliable knowledge of the history of his own people. He was aware of the importance of his research for the Norwegian people. He wanted to present the values of the past to the present, and so he placed great emphasis on certainty. Thus the terms “criticism” and “critical research” became central research maxims. This critical orientation initially led him to ask about the durability of historical views on the basis of the sources. In addition, the sources were checked for their credibility and usefulness. This attitude had to be reflected in the presentation of the results, as the criticism became part of the presentation itself and gave the reader the opportunity to convince himself of the durability of the statements. This led to extensive source reproductions over several pages within the treatises.

His basic orientation was on the "people" or the "tribe" as the basic terms. According to the prevailing view of the time, “tribe” and “people” were collective units that were constituted by an inner cultural context in which all elements of life were integrated. His central problem was to determine the place of the Norwegian people within the Scandinavian or Germanic context. This point of view and question is the central point in the so-called “norske historiske skole” (The Norwegian historical school).

His aim to show Norwegian culture as independent was also expressed in his attack on the Danske Oldskriftselskap (Danish Society for Old Scripts) because of its tendency to declare Icelandic literature to be the property of the Old Norse and emphasized the special connection between these old texts with Norway.

The Immigration Theory

The linguistic historical view of the conditions within the Germanic peoples led to the "immigration theory" which Keyser had developed, but which he continued and re-established. After that, Norway was settled from the north. The basis was the idea of a dividing line between North and South Germans, i.e. between Scandinavians and Germans who immigrated in different ways and at different times from their home region between the Urals and the Volga in the time before the birth of Christ. The later southern Germans had moved west to the south coast of the Baltic Sea, the later northern Germans had taken the route north, partly via the Gulf of Bothnia to Sweden, partly via Finnmarken to northern Norway. He claimed that there were originally three ethnic groups and that the Goths had settled further south in Scandinavia including Norway. These immigrations took place later and in areas without prior settlement.

This theory was suitable to explain both the linguistic and the social differences between the Germanic peoples that he thought he had ascertained. Immigration from the north explained why the “purest” Norwegian language forms were found in northern Norway. The fact that the areas were previously uninhabited should explain the originally "democratic" forms of society in later Norway and Sweden, i.e. the relative equality between the inhabitants. The Nordic language and the social conditions in Denmark and southern Scandinavia could be explained by the fact that the Norwegians penetrated there from the north and subjugated the Gothic population, which is why the language there was not so pure and the democratic elements were weaker.

Munch dealt intensively with the settlement history and cited the very early sources about the Håløy empire in the region of today's Hålogaland as evidence of immigration from the north . But he differed from Keyser in that he placed a special emphasis on the clan aristocracies and their opposition to royalty. Their gradual weakening of this aristocracy should have been the beginning of Norway's decline in the late Middle Ages.

Language reform

His research was linked to a linguistic and linguistic political goal. He wanted a new Norwegian written language instead of the previous Danish. He was against a mechanical “vernorwegization” by simply introducing Norwegian words or orthography into the dominant written language, as favored by Wergeland . Rather, he meant that one had to transform the language from the knowledge of the inner connection between the language and the Norwegian dialects and their connection with the Norrønen written language and preferred an etymologically based spelling. He was therefore very impressed by Ivar Aasen's work on a Norwegian vernacular. In his endeavors there are elements of the evolutionism then in progress . The language of each epoch must be adapted to the given level of development. Therefore he was against a reconstructed written language.

plant

He wrote several language textbooks, including in Old Norse (Norrøn) and Gothic. His production encompasses thousands of printed pages over many areas, but these were focused on his main work, Det Norske Folks Historie (history of the Norwegian people), which he was able to keep in eight volumes from 1851 to 1397. The first booklet appeared in 1851. At the same time he collected and organized source material in transcripts and published them and sagas, legal texts and diplomas in printed form. It seemed Norges Gamle Love (Norway old laws) in three volumes, the first volume of Diplamatarium Norvegicum and a long series of sagas and other ancient manuscripts. His main task was to copy old documents from the papal archives in Rome. It served the continuation of his history beyond the year 1319, from which there were also written sources. He published a total of 14 source texts, including the Older Edda, Speculum regale (Königsspiegel), the land register of the Munkeliv monastery, Historia Norvegiae and Chronica Regum Manniae et Insularum. His small study, Aufschluss über die Papalarchiv , published in Danish, was translated into German by Samuel Löwenfeld in 1880 .

Honors

Munch belonged to the congregation Norske Videnskabers Selskab and the Norwegian Academy of Sciences as well as several foreign academies. He was awarded the Order of Saint Olav in 1857 and the Order of the North Star in 1862 .

literature

This article is essentially based on the article "PA Munch" in Norsk biografisk leksikon . Additions are supported by special notes.

- Ottar Dahl: PA Munch. In: Norsk biografisk leksikon. ( snl.no ).

- Editor: Peter Andreas Munch (historian). In: Store norske leksikon. ( snl.no ).

- Ole Arnulf Øverland, Edvard Bull: Munch [moŋk], Peter Andreas . In: Christian Blangstrup (Ed.): Salmonsens Konversationsleksikon . 2nd Edition. tape 17 : Mielck – Nordland . JH Schultz Forlag, Copenhagen 1924, p. 406-407 (Danish, runeberg.org ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Peter Andreas Munch in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Øverland, Bull: Salmonsens Konversationsleksikon. P. 406.

- ↑ At that time, all students had to go through this faculty before they could devote themselves to individual subjects. This course led to the exam “philologico-philosophicum” or “anneneksamen” (second exam). It has the function of a compulsory Studium Generale. It imparted knowledge in philosophy, Greek, Latin, history, mathematics, natural history and, for theologians, Hebrew.

- ↑ Examination for admission to studies. Corresponds to today's Abitur, but was accepted by the university.

- ↑ a b c d Store norske leksikon.

- ↑ a b Øverland, Bull: Salmonsens Konversationsleksikon. P. 407.

- ^ Peter Andreas Munch: Information about the papal archive. Translated from the Danish by Samuel Löwenfeld, Berlin 1880.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Munch, Peter Andreas |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Munch, PA (short form) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Norwegian historian |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 15, 1810 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Christiania , Norway |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 25, 1863 |

| Place of death | Rome |