Paraplacodus

| Paraplacodus | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

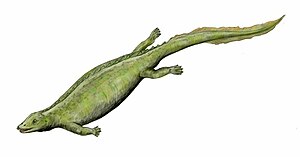

Paraplacodus , artistic representation of life |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Middle Triassic ( Anisium to Ladinium ) | ||||||||||||

| 247.2 to 235 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Paraplacodus | ||||||||||||

| Peyer , 1931 | ||||||||||||

| Art | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Paraplacodus is a genus of rather small marine reptiles of the purely fossil group of Placodontia from the Middle Triassic of Europe. To date only the type species , Paraplacodus broilli , is known.

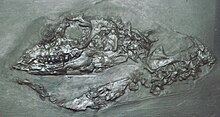

The first specimen of Paraplacodus was discovered on Monte San Giorgio in the canton of Ticino and described as a new genus by Bernhard Peyer in 1931 . Until the year 2000, the genus was only known from this locality, which also provided the most extensive and best-preserved material. Only then were some less well-preserved and partly very incomplete finds from the Netherlands ( Winterswijk ), Germany (several locations), Poland ( Tarnowskie Góry ) and Romania ( Brașov ) reported.

etymology

The name Paraplacodus (Greek παρα- para- , against, next to, in comparison with ') indicates the numerous similarities with the relatively closely related genus Placodus from Central Europe north of the Alps, which was first described in 1833 .

features

Paraplacodus belonged to the smaller genera of the Placodontier. It reached a head-to-tail length of about 1.2 meters, with the tail being about the same length as the rest of the body.

Like Placodus , Paraplacodus has three clearly protruding premaxillary teeth ("incisors"), but in Paraplacodus these are conical-pointed, while in Placodus they are chisel-shaped. The number of maxillary teeth ("molars") in Paraplacodus is about twice as high as in Placodus , whereby the crowns in Paraplacodus are stocky, but significantly higher and slimmer than in Placodus and sometimes taper in a pointed arch- like manner. The same goes for the teeth of the lower jaw. In Paraplacodus , the tooth-bearing bone of the lower jaw (dental), in contrast to Placodus, has an only poorly developed coronoid process (processus coronoideus), so that the coronoid (a non-tooth-bearing lower jaw bone adjoining the dental) is not covered by the coronoid process when viewed from the lip. The middle roof bone (palatinum) has three flat, massive teeth in Placodus and at least four in Paraplacodus , which in Placodus are each slightly larger and slightly narrower than in Paraplacodus . In both genera, the inner nostrils (choans) are fused to form a single opening, lying on the symmetry axis of the skull, framed by the front ends of the palatina. complete paragraph after

The trunk skeleton of Paraplacodus , like that of Placodus , is characterized by the fact that the lateral (lateral) end pieces of the abdominal ribs (gastralia) are characteristically bent upwards (dorsad) at approximately right angles. However, there are clear differences between the two genera in the trunk spine and associated structures: While Placodus has high spinous processes, each associated with an osteoderm , Paraplacodus has low spinous processes and no back osteoderms.

Distribution and way of life

Paraplacodus was native to the shallow coastal waters of the northwestern Tethys and in the Muschelkalkmeer in the Germanic Basin to the north . Finds of this genus make up only 5% of all placodont animal finds in the Germanic Basin, while in the north-western Tethys (especially on Monte San Giorgio) it is 29%.

Like Placodus , Paraplacodus is generally considered to be durophag, that is, its diet was based on hard-shelled marine animals such as mussels, snails and brachiopods, with the massive, flat palatal teeth serving in particular to crack the shell. Its coronoid process, which is less developed than Placodus , indicates less pronounced jaw muscles and therefore less specialization in this way of life. This is also suggested by the more “primitive” formation of the premaxillary and maxillary teeth compared to Placodus (see above ).

According to a controversial alternative hypothesis, placodon animals are seen as ecological counterparts of the manatees and Paraplacodus in their evolutionary series as the counterpart of the Eocene manatee Protosiren . He is said to have used his front teeth to pluck off and dig up seaweed-like aquatic plants (macroalgae) and his maxillary and palatal teeth to crush their thalli ("leaves") or rhizomes ("roots"). These algae meadows, for which there is no direct fossil record should focus on the submarine Ooid have extended sand barren, which, in the form of today oolitic limestone, including the so-called Schaumkalkzone Lower Muschelkalk distinguished.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bernhard Peyer: paraplacodus broilii nov. gen. nov. sp., a new placodon animal from the Ticino Triassic. Preliminary communication. Central Journal for Mineralogy, Geology and Paleontology. Department B: Geology and Paleontology. 1931, ZDB -ID 123992-2 , pp. 570-573.

- ↑ a b c d Olivier Rieppel: Paraplacodus and the phylogeny of the Placodontia. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. Vol. 130, No. 4, 2000, pp. 365-359, doi: 10.1006 / zjls.2000.0232 (Open Access).

- ↑ a b c d e Cajus G. Diedrich: Fossil middle triassic "sea cows" - placodont reptiles as macroalgae feeders along the north-western tethys coastline with pangea and in the germanic basin. Natural Science. Vol. 3, No. 1, 2011, pp. 9-27, doi: 10.4236 / ns.2011.31002 .

- ^ Hans Peter Rieber: Monte San Giorgio and Besano, middle Triassic, Switzerland and Italy. P. 83–90 in: Dieter Meischner (Ed.): European fossil deposits. Springer, 2000, ISBN 3-540-64975-1 , p. 88.

- ↑ a b Torsten M. Scheyer, James M. Neenan, Silvio Renesto, Franco Saller, Hans Hagdorn, Heinz Furrera, Olivier Rieppel, Andrea Tintori: Revised paleoecology of placodonts - with a comment on 'The shallow marine placodont Cyamodus of the central European Germanic Basin: its evolution, paleobiogeography and paleoecology 'by CG Diedrich (Historical Biology, iFirst article, 2011, 1-19, doi: 10.1080 / 08912963.2011.575938 ). Historical Biology. Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 257-267, doi: 10.1080 / 08912963.2011.621083 .

- ↑ Stephanie B. Crofts, James M. Neenan, Torsten M. Scheyer, Adam P. Summers: Tooth occlusal morphology in the durophagous marine reptiles, Placodontia (Reptilia: Sauropterygia). Paleobiology. Vol. 43, No. 1, 2017, pp. 114–128, doi: 10.1017 / pab.2016.27 .

- ↑ Andrea Tintori: Comment on “The vertebrates of the Anisian / Ladinian boundary (Middle Triassic) from Bissendorf (NW Germany) and their contribution to the anatomy, palaeoecology, and palaeobiogeography of the Germanic Basin reptiles” by C. Diedrich [Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology , Palaeoecology 273 (2009) 1-16]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. Vol. 300, No. 1–4, 2011, pp. 205–207, doi: 10.1016 / j.palaeo.2010.12.010 .

- ^ A b Cajus G. Diedrich: Palaeoecology of Placodus gigas (Reptilia) and other placodontids - Middle Triassic macroalgae feeders in the Germanic Basin of central Europe - and evidence for convergent evolution with Sirenia. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. Vol. 285, No. 3/4, 2010, pp. 287–306, doi: 10.1016 / j.palaeo.2009.11.021 .