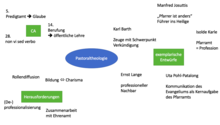

Pastoral theology

Pastoral theology is a special discipline in the canon of Christian theology . Their exact demarcation differs from one denomination to another. In Catholic theology , the term was coined in the 18th century by Franz Stephan Rautenstrauch and until the 20th century it was mostly understood as congruent with the entire practical theology ; It is only recently that the term practical theology has been used here as well. In Protestant theology , since Friedrich Schleiermacher , it has been understood as a sub-area of practical theology, namely the doctrine of nature, office, profession and role of the pastor.

Topic and task

Pastoral Theology studied on a solid doctrinal basis of the theological relevance of faith for the pastoral ( pastoral ) monitoring and care in the church ground full trains of " martyrdom " (testimony of the word), "Diakonia" (service of love, Diakonie ) and " Leiturgia " ( celebration of worship, liturgy ). In this way the shepherds (“pastores”) in particular, together with their other co-workers, are to be enabled “to seek the solution of human problems in the light of revelation, to apply their eternal truth to the changeable world of human things and to adapt it to the people of our time to communicate. "( Optatam totius , No. 16)

Pastoral theology needs interdisciplinary cooperation in order to achieve its goal, from which special disciplines such as pastoral anthropology, pastoral medicine , pastoral psychology , pastoral pedagogy and pastoral sociology are derived.

Pastoral theology as a professional theory of the parish office

Principles from the Confessio Augustana

Article 5 of the CA sees in the preaching office a possibility given by God to gain faith (according to the principle "fides ex auditu" - faith comes from hearing): "In order to attain this faith, God established the preaching office".

Article 14 stipulates that public teaching and sermon as well as the administration of the sacraments should take place through the church government or church office, for which a "proper calling" is required.

Article 28 formulates the principle "non vi sed verbo" for church leadership - not by force, but with the word. The management should not enforce anything by force, but always endeavor to win over with words.

Current practical theological reflection

Ulrike Wagner-Rau designs in her contribution to “Practical Theology. A textbook "(2017) under the heading" Pastoral Theology "vocational theory of parish office . Particularly challenging are the scarcity of resources, which requires conceptual thinking, the way of life in which private and professional life has to be balanced, the dissolution of the assignment of a pastor to only one parish and the mostly unpredictable familiarity of people with Christian religious practice, which is a theological and requires communicative competence.

The structural conditions of the pastor's profession include, above all, its peculiarity as a profession of conviction (tension between faith and doubt), public communication of the gospel as a central task with a lot of leeway, the residence obligation , lifelong ordination , academic training including further training in the vicariate and further offers for reflection , the privilege over other church professions and the management function in most church tasks (often church council, management of kindergarten , cemetery , ...). As different forms of parish service, there are parish parish offices with local parish activities, functional parish priests specializing in a certain task (e.g. hospital or prison chaplaincy, media work, ...), parish services in higher levels of church leadership (deans / superintendents / provosts), partial employment relationships and parish services on a voluntary basis . The challenge is the diffusion of roles: In the pastoral office it is sometimes not easy to distinguish between personal and professional roles because privacy cannot always be strictly separated from work.

From an empirical point of view, the image of church and pastor are closely related. For example, it becomes clear that personal contacts between church members and pastors are usually positively remembered, while members without contact with the pastor have a higher tendency to leave. The self-image of pastors largely corresponds to the expectations of the members: Pastoral care and preaching are usually the main focuses of work, which are often carried out with great satisfaction. The image of the pastor's profession has been culturally constructed in fiction since the 18th and 19th centuries, today also in film and television, which has a lasting impact on the public's expectations of the pastor.

In the New Testament there is a tension between the special calling of the followers of Jesus through special tasks (preaching, healing, forgiveness of sins, ...) and anti-hierarchical approaches (e.g. Jesus' attitude to the dispute over rank), which in a certain way continues in the Protestant understanding of the Reformation that on the one hand the ordination is lifelong and specifically qualified for the public communication of the gospel, but on the other hand the understanding of ministry is not sacramental (catholic), but functional (parish profession has the same position as all other professions). Due to the change in the understanding of the pastoral office during the Reformation, the pastor primarily became a “scribe” with the primary task of interpreting scriptures (in preaching, education, pastoral care, ...), who should therefore not only bring with him a vocation, talent and charisma, but also one Theological education, in which it is important to combine scientific-critical and pious approaches to reality in one person. In the 19th century, the pastor's profession became increasingly professional because the regular salary made it possible to concentrate on spiritual tasks, because the pastor no longer had to rely on economic income, for example from agriculture, whereas already from the second half of the 19th century A deprofessionalization can be observed in the 19th century, which goes hand in hand with the differentiation of professions and thus with the outsourcing of tasks (teaching, medical, nursing, socio-educational ...) to others. Due to subjectification and individualization, pastors in the 20th century have to adjust to the subjectivity of their counterparts and, due to the differentiation of society, the living and working worlds are less manageable, and there are new tasks for the pastors (adult educators, leisure entertainers, shapers of the community, ...) added. As far as gender issues are concerned, it should be noted that women have only had the opportunity to study theology since the Weimar Constitution, with the first ordinations of women only being carried out in the Confessing Church during the Second World War. The demand for equal rights for men and women, anchored in the Bonn Basic Law, ecumenical impulses and the “New Women's Movement” finally led to equal rights for men and women in the pastoral office in the 1960s / 1970s, which today in the EKD is about 33% women represented, with more women in part-time employment and still under-represented in management positions.

As spiritual leaders, pastors have overall theological responsibility, which they fulfill in the core tasks of worship, preaching, pastoral care and educational work - be it in the sense of Karl Barth's dialectical theology as a witness with the focus on preaching, or in the sense of Ernst Lange as a professional neighbor, who knows how to interpret life in casualia, who acts to help in diakonia and, overall, as a religiously sensitive dialogue partner, can convey orientating values. The quality of the pastor's profession can be seen both as a spiritual one, which is characterized by the reference to the power field of the saint (Josuttis), as well as a theological one, through the pastors self-reflective and critical biblical texts for contemporary issues, taking into account their own limitation and with a plurality competence that is open to different positions and styles of piety. Isolde Karle illuminates the pastoral office as a profession, i.e. as a special profession for certain tasks with corresponding educational requirements. Uta Pohl-Patalong sees the core task of the pastor in the communication of the Gospel, however not in the sense of a reduction to preaching, but with regard to the diverse areas of responsibility. Ulrike Wagner-Rau describes elsewhere the "task of public communication of the gospel 'on the threshold'". The ministry cannot be viewed in isolation from the person (as in the job description of dialectical theology), but they influence each other, so that Meyer-Blanck can say that the presence and authenticity of the pastor are essential for staging the gospel.

Currently discussed are the dissolution of the integral way of life of the rectory, which previously strongly linked professional and private life, but is subject to change due to social changes (employment of men and women in one family at the same time, same-sex partnerships, single households, ...), but is subject to changes in working hours the prioritization of priority areas of church work and the relationship between the pastor's office and other active members of the community (musicians, educators, deacons, volunteers), who are mostly structurally disadvantaged, but who are becoming increasingly important due to the lack of theological offspring.

For the future, the question arises, on the one hand, of how the attractiveness of the profession can be preserved for the currently too scarce offspring in view of the overall religious situation in Central Europe; on the other hand, the question from the 1980s arises again as to the extent to which the parish profession is also productive can relate to the local socio-spatial situation.

Literature (selection)

- Johann Michael Sailer : Lectures from Pastoral Theology , Munich 1793

- Walter Fürst , Friedemann Merkel : Pastoral Theology . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 26, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1996, ISBN 3-11-015155-3 , pp. 70-83.

- Herbert Haslinger: Pastoral Theology . Schöningh, Paderborn 2015. ISBN 978-3-8385-8519-2

- Christian Möller : Introduction to Practical Theology . Tübingen 2004. ISBN 3-7720-3012-2

- Norbert Mette : Introduction to Catholic Practical Theology . Darmstadt 2005. ISBN 3-534-15200-X

- Gerhard Rau: Pastoral Theology . In: Religion Past and Present (RGG). 4th edition. Volume 6, Mohr-Siebeck, Tübingen 2003, Sp. 996-1000.

- Heribert Wahl (Ed.): Dare to "leap forward" again. Pastoral theology "after" the council; Review and Outlook , Würzburg 2009 (= Studies on theology and practice of pastoral care, Volume 80).

- The largest Catholic specialist magazine for pastoral care and community work in the German-speaking area is the Anzeiger für die Seelsorge published by Herder, a publisher in Freiburg .

- The most important scientific Catholic journals are Diakonia ( published by Herder ) and Lebendige Seelsorge (published by Echter ).

- The most important Protestant journals are Pastoral Theology with Göttingen Sermon Meditations (PTh) and Paths to People (WzM), both published by Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen.