Paul Gruner (physicist)

Franz Rudolf Paul Gruner (born January 13, 1869 in Bern ; † December 11, 1957 there ) was a Swiss physicist .

Life

He attended the grammar school in Morges , the free grammar school in Bern , and passed the Matura at the municipal grammar school in Bern. He then studied at the universities of Bern , Strasbourg , and Zurich . He received his doctorate in 1893 under Heinrich Friedrich Weber in Zurich. Then (1893–1903) he taught physics and mathematics at the free grammar school in Bern. In 1894 he completed his habilitation in physics and became a private lecturer , from 1904 titular professor in Bern. There he was associate professor from 1906 to 1913 , and finally full professor for theoretical physics from 1913 to 1939 (first in Switzerland). From 1921 to 1922 he was rector of this university.

In 1892 he became a member of the Natural Research Society in Bern, in 1898 he was its secretary, from 1904 to 1906 and from 1912 to 1914 vice-president and president, from 1939 an honorary member. He was also a member of the Swiss Society for Natural Sciences , of which he was Vice President from 1917 to 1922. He was also a member of the Swiss Physical Society , of which he was Vice President from 1916 to 1918 and President from 1919 to 1920. He participated in the founding of the physics journal Helvetica Physica Acta , was president of the Federal Meteorological Commission, and in connection with his Christian worldview and his rejection of materialism , he became a member of the Keplerbund .

Gruner's estate is in the Bern Burger Library .

Scientific work

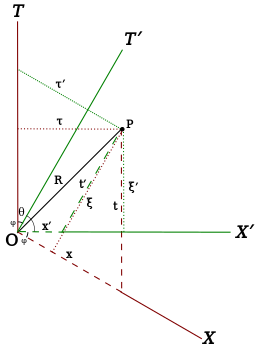

He has authored academic and popular science papers on a range of topics. Particularly known for his work were the optics of turbid media and dawn phenomena , but he also published in the fields of relativity and its graphical representation by means of special Minkowski diagrams , radioactivity , electron theory , kinetic theory of gases , thermodynamics , quantum physics .

Gruner and Einstein

Albert Einstein was introduced to the Natural Research Society in Bern in 1903 by a colleague at the patent office in Bern, Josef Sauter , where he met Sauter's friend Paul Gruner, who was then a private lecturer in theoretical physics. Einstein gave a few lectures in Gruner's house and from then on corresponded with him. In 1907 Einstein applied for his habilitation as a private lecturer and was supported by Gruner, now associate professor in Bern. In 1908 Einstein finally became a private lecturer in Bern.

Minkowski diagram

From May 1921, Gruner and Josef Sauter developed symmetrical Minkowski diagrams. In works from 1922 to 1924 he expanded his analyzes. (See Minkowski Symmetrical Diagram for math details).

In 1922 he explained that the construction of such diagrams allowed the introduction of a third reference system with orthogonal space and time axes, as in ordinary Minkowski diagrams. As a result, it is possible that the coordinates of the other two inertial systems and are projected onto these axes, whereby a so-called “universal reference system” with “universal coordinates” can be created for one system pair in each case. Gruner explained that there is no contradiction to the theory of relativity, since these coordinates are only valid for one system pair. He added that he wasn't the first to use universal coordinates, referring to two precursors:

Edouard Guillaume analyzed two inertial systems in 1918 and claimed to have found a universal time in the sense of Galileo-Newtonian mechanics, which he interpreted as a contradiction to the theory of relativity. For details on discussions with the relativity critic Guillaume, see Genovesi (2000).

Guillaume's mistake was revealed by Dmitry Mirimanoff (March 1921), who showed that there is no contradiction to the theory of relativity. Guillaume's universal time is derived from the time of a "mean system" between two inertial systems by applying a constant factor. According to Mirimanoff, a mean system is defined in that, from its perspective, two inertial systems are moved at the same speed in opposite directions. Consequently, this "universal" time only applies to a single system pair, since it depends on the respective relative speed of the two systems under consideration. It therefore has no further physical meaning. Gruner also came to the same conclusion as Mirimanoff and praised him for the correct interpretation of these "universal systems". Gruner also praised Guillaume as the first to grasp certain mathematical relationships, but criticized him for the incorrect interpretation and, related to it, his misguided criticism of the SRT.

Publications

- Paul Gruner: Astronomical Lectures . Nydegger Baumgart., Bern 1898.

- Paul Gruner: The radioactive substances and the theory of atomic decay . A. Francke, Bern 1906.

- Paul Gruner: Short textbook of radioactivity. A. Francke, Bern 1911.

- Paul Gruner: Guide to Geometric Optics . P. Haupt, Bern 1921.

- Paul Gruner: Elements of the theory of relativity . P. Haupt, Bern 1922.

- Paul Gruner, Heinrich Kleinert: twilight phenomena . H. Grand, Hamburg 1927.

- Paul Gruner: Human ways and God's ways in student life. Personal memories from the Christian. Student movement . BEG-Verlag, Bern 1942.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jost, p. 109.

- ↑ a b Mercier, p. 364.

- ↑ Jost, p. 112

- ↑ Hool & Graßhoff, p. 63

- ↑ Bebié, p. 230.

- ↑ Paul Gruner's estate in the catalog of the Burgerbibliothek Bern

- ↑ Jost, pp. 111-112

- ↑ Mercier, pp. 365–369 (detailed catalog of works)

- ^ Fölsing, pp. 132, 260, 273.

- ^ Paul Gruner, Josef Sauter: Representation géométrique élémentaire des formules de la théorie de la relativité . In: Archives des sciences physiques et naturelles . 3, 1921, pp. 295-296.

- ↑ Paul Gruner: An elementary geometric representation of the transformation formulas of the special theory of relativity . In: Physikalische Zeitschrift . 22, 1921, pp. 384-385.

- ^ Paul Gruner: Elements of the theory of relativity . P. Haupt, Bern 1922.

- ↑ Paul Gruner: Graphical representation of special relativity theory in four-dimensional space-time world I . In: Journal of Physics . 10, No. 1, 1922, pp. 22-37. doi : 10.1007 / BF01332542 .

- ↑ a b c Paul Gruner: Graphic representation of the special theory of relativity in the four-dimensional space-time world II . In: Journal of Physics . 10, No. 1, 1922, pp. 227-235. doi : 10.1007 / BF01332563 .

- ↑ a b c d Paul Gruner: a) Représentation graphique de l'univers espace-temps à quatre dimensions. b) Representation of the graphique du temps universel dans la théorie de la relativité . In: Archives des sciences physiques et naturelles . 4, 1921, pp. 234-236.

- ↑ Paul Gruner: The meaning of “reduced” orthogonal coordinate systems for tensor analysis and the special theory of relativity . In: Journal of Physics . 10, No. 1, 1922, pp. 236-242. doi : 10.1007 / BF01332564 .

- ↑ Paul Gruner: Geometric representations of the special theory of relativity, especially the electromagnetic field of moving bodies . In: Journal of Physics . 21, No. 1, 1924, pp. 366-371. doi : 10.1007 / BF01328285 .

- ↑ Edouard Guillaume: La théorie de la relativité en fonction du temps universel . In: Archives des sciences physiques et naturelles . 46, 1918, pp. 281-325.

- ↑ Angelo Genovesi: Il carteggio tra Albert Einstein and Edouard Guillaume: “tempo universale” e teoria della relatività ristretta nella filosofia francese contemporanea . FrancoAngeli, 2000, ISBN 88-464-1863-8 .

- ↑ Mirimanoff, Dmitry: La transformation de Lorentz-Einstein et le temps universel de M. Ed. Guillaume . In: Archives des sciences physiques et naturelles (supplement) . 3, 1921, pp. 46-48.

- ^ Paul Gruner: Quelques remarques concernant la theory de la relativite . In: Archives des sciences physiques et naturelles . 5, 1923, pp. 314-316.

literature

- Jost, W .: Prof. Dr. Paul Gruner: 1869-1957 . In: Communications from the Natural Research Society in Bern . 16, 1958, pp. 109-114.

- Mercier, André: Paul Gruner . In: Negotiations of the Swiss Natural Research Society . 138, 1958, pp. 363-364.

- Bebié, Hans: Gruner, Franz Rudolf Paul. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 7, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1966, ISBN 3-428-00188-5 , p. 230 ( digitized version ).

- Albrecht Fölsing: Albert Einstein. A biography . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-518-38990-4 .

- Alessandra Hool, Gerd Graßhoff: The foundation of the Swiss Physical Society: Festschrift for the centenary . Bern Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science, 2008, ISBN 978-3-9522882-8-3 .

Web links

- Paul Gruner in the catalog of the Burgerbibliothek Bern

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gruner, Paul |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gruner, Franz Rudolf Paul (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Swiss physicist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 13, 1869 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bern |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 11, 1957 |

| Place of death | Bern |