Article 8 of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany

Article 8 of the German Basic Law (GG) guarantees the freedom of assembly . It is part of the first section of the Basic Law, in which fundamental rights are guaranteed. Freedom of assembly is the right to freely assemble privately or in public, peacefully and without weapons. Art. 8 GG is of particular practical importance in connection with public demonstrations in which free assembly promotes participation in the formation of public opinion. Therefore there is a close connection between him and the freedom of expression guaranteed in Art. 5 GG and other fundamental rights of communication.

Freedom of assembly can be restricted by conflicting constitutional law. Of particular practical importance here is the state obligation to protect the life and limb of its citizens , which follows from Article 2, Paragraph 2, Sentence 1 of the Basic Law. In paragraph 2 of Art. 8 GG this is taken into account as follows:

“For meetings in the open air, this right can be restricted by statute or on the basis of a statute.”

Essentially, this is done by the assembly laws of the Federation and some federal states.

Normalization

Since the Basic Law came into force on May 24, 1949, Article 8 of the Basic Law has read as follows:

(1) All Germans have the right to assemble peacefully and without weapons without registration or permission.

(2) For meetings in the open air, this right can be restricted by statute or on the basis of a statute.

The freedom guaranteed by Art. 8 GG primarily serves to ward off sovereign interference by holders of fundamental rights , which is why it represents a right of freedom . As a collective form of forming and expressing opinions, the freedom of assembly is closely related to the fundamental rights of communication protected by Art. 5 GG. The Federal Constitutional Court therefore regards the freedom of assembly as well as the fundamental rights of communication as constituting the basic democratic order.

Art. 8 GG bindsthe three state powers executive , legislative and judiciary in accordance with Art. 1 Paragraph 3 GG. Citizens and associations of private law are therefore not bound by the fundamental right. Demarcation difficulties arise with regard to the fundamental rights obligation in companies organized under private law, in which both private and public authorities participate. The Federal Constitutional Court considers such companies to be fully bound by fundamental rights, provided that the public sector controls the company. This is true if more than 50% of the company is publicly owned.

History of origin

The basic right of Article 8 of the Basic Law goes back historically to § 161 of the Paulskirche constitution of 1848. This norm was created under the influence of state attempts to restrict political assemblies in particular, for example through the Karlsbad resolutions of 1819 or the repression following the Hambach Festival of 1832. Section 161 of the Paulskirchenverfassungs guaranteed all Germans the right to assemble peacefully and without arms . However, gatherings in the open air could be prohibited if there was an imminent danger to public safety or order. However, the Paulskirche constitution did not prevail due to the resistance of numerous German states, so that its § 161 had no legal effect. However, some states took up the guarantees of the failed constitution and as a result introduced the rights of assembly into their constitutions, the scope of which in some cases reached that of Section 161, and in some cases clearly lagged behind it.

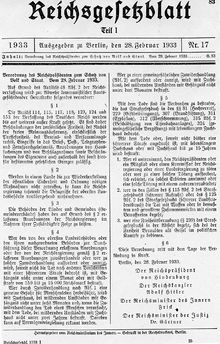

The Weimar Constitution (WRV) of 1919 guaranteed a right to freedom of assembly with Article 123. The scope of this guarantee corresponded to that of the earlier § 161 of the Paulskirche constitution. Art. 123 WRV was repealed under the ordinance of the Reich President for the protection of people and state of February 28, 1933.

After the Second World War , the Parliamentary Council developed a new constitution for the Federal Republic of Germany between 1948 and 1949. In the course of this, he decided to include freedom of assembly in the catalog of fundamental rights of the new constitution. It implemented this through Article 8 of the Basic Law. This provision has remained unchanged in its wording since the Basic Law came into force.

The legal dogmatics of freedom of assembly was significantly shaped by the Brokdorf decision of 1985. In the course of this procedure, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled for the first time on the admissibility of a ban on assembly . The complainants were demonstrators who demonstrated against the construction of the nuclear power plant in Brokdorf . The demonstration was banned , citing a violation of the registration requirement under Section 14 of the Assembly Act (VersammlG). The court found a violation of freedom of assembly and upheld the complaint. In this landmark ruling , the Federal Constitutional Court developed some basic guidelines for the interpretation of Article 8 and assessed the relationship between the fundamental right and the Assembly Act.

Protection area

Freedom of assembly protects citizens from restrictions on their right to assemble. To this end, it guarantees a sphere of freedom that sovereigns may only intervene under certain conditions . This sphere is called the protection area . If a sovereign intervenes in this and this is not constitutionally justified, he thereby violates the freedom of assembly.

Jurisprudence differentiates between the personal and factual areas of protection. The personal protection area determines who is protected by the fundamental right. The objective area of protection determines which freedoms are protected by the fundamental right.

Personally

All Germans are the bearers of the fundamental right under Article 8 (1) of the Basic Law. Pursuant to Article 116, Paragraph 1 of the Basic Law, all German citizens are deemed to be Germans . Persons who do not have German citizenship are therefore not protected by Art. 8 GG. However, they also have the right to assemble freely. Under constitutional law, this is anchored in the basic right of general freedom of action ( Art. 2 Paragraph 1 GG). As a result, only the differentiated system of rules does not apply to meetings of foreigners. Under simple law, everyone has a right of assembly from Section 1 (1) of the General Assembly Act.

Is controversial in the jurisprudence, whether citizens from other Member States of the European Union on Art. 8 can appeal 1 GG paragraph. According to one opinion, the prohibition of discrimination in Article 18 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) requires Union citizens to be treated as Germans within the framework of German rights . According to this, they would also be carriers of the fundamental right formulated in Art. 8 Paragraph 1 GG. The opposite view assumes that such an interpretation contradicts the unambiguous wording of German law. The equal treatment required by Art. 18 TFEU can be ensured by the fact that the evaluations of Art. 8 Paragraph 1 GG apply to EU foreigners when Art. 2 Paragraph 1 GG is applied. The Federal Constitutional Court has not yet taken a clear position on this question. This dispute, which also applies to other German rights, such as the freedom of occupation ( Art. 12, Paragraph 1 of the Basic Law), has little practical relevance for freedom of assembly, since the assembly laws are not restricted to Germans, but grant everyone the right to assemble.

Domestic associations of persons , in particular legal persons under private law, can be holders of freedom of assembly in accordance with Art. 19 Paragraph 3 GG. A legal person is domestic if its actual center of action is in the territory of the Federal Republic. In order for a fundamental right to be applicable to an association, it must, by its very nature, be applicable to it. For the freedom of assembly, the essential applicability results from the fact that associations of persons are able to organize and hold events.

In addition to the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany, the right of assembly is also the subject of German state constitutions . They grant different groups of people the right to assemble freely: The Berlin constitution gives it to “all men and women”, the Brandenburg constitution “all people” and the Hesse constitution “all Germans”.

Factual

The Basic Law does not define the term assembly. The Federal Constitutional Court understands this as a local meeting of several people for a common purpose.

There is disagreement in jurisprudence as to how many people a meeting requires at least. The prevailing view is based on the assumption that two people already form an assembly, since the protective function of Art. 8 GG can meaningfully come into play from this size . Other voices call for three or seven participants. The practical relevance of this issue is little, however, since more than seven people regularly form a congregation. Therefore, the Federal Constitutional Court has not yet taken a position on this.

The requirement of a common purpose distinguishes the gathering from the mere gathering of people that occurs, for example, in a group of onlookers . It is controversial in jurisprudence what quality the common purpose must have. The Federal Constitutional Court advocates the narrow concept of an assembly. According to this, Art. 8 GG only protects those assemblies that serve to form public opinion. It therefore did not evaluate the Love Parade as a gathering, for example , as it only served to collectively showcase an attitude towards life. The court argues that freedom of assembly is historically closely related to free political communication. The fundamental right therefore primarily aims to protect the collective formation and expression of opinion. Numerous legal scholars argue against this view that it restricts the scope of protection of Art. 8 GG too much. For a meeting to be worthy of protection, it is irrelevant whether it is aimed at the formation of public opinion. The purpose of freedom of assembly is to promote the collective development of personality through holding meetings. In addition, with the narrow approach, there is the risk that the concept of assembly is no longer used as flexibly and adaptably as would be necessary for an effective protection of fundamental rights. Therefore, the common purpose does not have to have a special quality.

The scope of protection of Article 8 GG does not depend on whether an assembly is subject to registration and is accordingly registered, but it ends with the lawful dissolution of the assembly.

Peaceful and unarmed

Since the freedom of assembly serves collective communication, Art. 8 GG only protects assemblies that are peaceful and unarmed.

A meeting is unarmed if its participants do not carry any weapons within the meaning of the Weapons Act or other objects that are suitable for the violation of foreign legal interests and are intended for this purpose. Protective weapons , such as shields and masks, are not weapons.

An assembly that is non-violent and does not endanger any foreign legal interests is peaceful. The Federal Constitutional Court interprets the criterion of peacefulness widely, since it is in the nature of large gatherings in particular to disrupt everyday life. In accordance with the Assembly Act, it only considers an assembly to be unpeaceful if it takes a violent or seditious course as a whole. This applies if acts of violence and dangers emanate from the assembly, for example aggressive rioting against people or property. Violence occurs when there is an active physical influence on someone else's legal asset. The concept of violence is thus more narrowly defined within the framework of Art. 8 GG than in criminal law. Therefore, a sit-down can indeed fulfill the objective fact of coercion with force ( § 240 StGB), but still count as a peaceful gathering. Violations of legal provisions do not necessarily lead to the assessment of an assembly as unpeaceful, since the criterion of peacefulness would otherwise be ineffective alongside the simple legal reservation of Article 8, Paragraph 2 of the Basic Law, which allows the restriction of freedom of assembly. This also includes violations of criminal law by individual participants.

The assumption of dissatisfaction also presupposes that the violence emanates from the majority of the meeting participants or is at least approved. Therefore, a meeting does not become unpeaceful just because individual participants behave unpeacefully. If an assembly is divided into peaceful and unpeaceful groups, the freedom of assembly in favor of the peaceful group is unrestrictedly effective.

The assumption of dissatisfaction is also possible if there is only a threat of violence. Because of the basic rights protection of assemblies, the Federal Constitutional Court demands a forecast that assumes a high probability of violence. The case law regards the masked appearance of meeting participants as an indication of this .

Protected behavior

The behavior protected by the freedom of assembly includes the preparation and follow-up of an assembly, the choice of the place and time of the meeting, the organization and its design. However, the right to free choice of location does not in principle establish the right to use someone else's property without the owner's permission. In the course of the G20 summit in Hamburg 2017 , the question arose whether and under what conditions protest camps are considered part of an assembly. This has not yet been conclusively clarified in law.

If, however, a place with otherwise restricted access and purpose, such as a cemetery, becomes a general communicative forum through a public memorial event, then the scope of protection of Article 8 also applies to counter-demonstrators at such an event.

Attending a meeting in order to harm it is not protected, as this behavior is not worthy of protection. Furthermore, the freedom of assembly does not serve to protect activities in the form of assembly that would be prohibited for individuals. After all, the basic right does not give rise to a foreign head of state's right to perform a political function in Germany. Otherwise the more specific foreign policy rules would be circumvented.

Fundamental rights competitions

If the area of protection of several fundamental rights is affected in one issue, these are in competition with one another.

As a special right to freedom, Art. 8 GG is more specific than the general freedom of action ( Art. 2 Paragraph 1 GG). On the basis of Art. 2 Paragraph 1 GG, assemblies only judge themselves to the extent that they do not fall under Art. 8 GG. This is particularly true of gatherings of foreigners.

The fundamental rights of communication of Art. 5 GG are due to their protection purpose different from Art. 8 GG in principle next to the freedom of assembly. Both fundamental rights are often protected during demonstrations. Insofar as an encroachment on fundamental rights is directed exclusively against a statement in connection with the assembly, only Article 5 of the Basic Law is affected.

Also in addition to the freedom of assembly is by virtue of their independent protected interest Art. 9 protected GG freedom of association .

Intervention

An encroachment occurs when the guarantee content of a basic right is shortened by sovereign action.

Art. 8 paragraph 1 GG names two typical forms of targeted interference with the freedom of assembly: The obligation to register and approve an assembly. Other frequently occurring interventions are the issuing of conditions against the meeting, the exclusion of participants and the dissolution of the meeting. Taking pictures of meeting participants is also of an encroaching nature, as this can have an intimidating effect on citizens, which can discourage them from using the freedom of assembly. Finally, purely actual obstacles to an assembly can also constitute an encroachment on fundamental rights, for example making it more difficult to access the location of the assembly.

Justification of an Intervention

If there is a sovereign interference with the freedom of assembly, this is lawful if it is constitutionally justified. According to Art. 8, Paragraph 2 of the Basic Law, the conditions under which a justification is possible are based on the circumstances under which a meeting is organized.

Simple legal reservation

Art. 8 GG

Article 8 paragraph 2 of the Basic Law contains a legal reservation that refers to meetings in the open air. Such gatherings may be restricted by law.

Assembly in the open air

With the concept of an open-air assembly, the constitutional giver described an assembly that is held in a location that is freely accessible to the public. This typically applies to those gatherings that take place in public paths and places. Meetings that take place inside buildings can also be held in the open air, provided they are open to the public. The Federal Constitutional Court affirmed this for a meeting at Frankfurt Airport , for example .

The fact that Art. 8, Paragraph 2 of the Basic Law provides a specific legal reservation to intervene in meetings in the open air, is based on the special need for regulation that exists in such meetings: Publicly accessible meetings tend to conflict with their surroundings more than those that are spatially different from their surroundings delimit. Hence, from the point of view of the state, there is a greater need to control the course of the gathering. An intervention can take place directly through a parliamentary act, for example through the Federal Assembly Act, or through a legal act that is enacted on the basis of a parliamentary act, for example an administrative act .

According to the quotation requirement standardized in Art. 19, Paragraph 1, Clause 2 of the Basic Law , a law that restricts the freedom of assembly must expressly state this, stating Art. 8 of the Basic Law. The citation requirement is intended to make it clear to the legislature that it is restricting a fundamental right. In the Federal Assembly Act (VersammlG), this was done, for example, through Section 20 Assembly Act.

Federal Assembly Act

The Federal Assembly Act of 1953 is a central source of law from which restrictions on the freedom of assembly result. This regulates the legal framework for assemblies. As a more specific law , it supersedes general police and regulatory law . Therefore, sovereign interventions, especially in ongoing meetings, can in principle only be based on the Assembly Act. This blocking effect of the right of assembly is referred to in jurisprudence as the police resistance of freedom of assembly. However, the primacy of the Assembly Act only extends to the extent that it contains its own regulations. In matters that it does not cover, it is therefore possible to resort to other laws. Therefore, among other things, regulations for the defense against dangers that are not specific to the assembly but, for example, are of a construction or health law nature are not blocked .

The Assembly Act was enacted on the basis of the earlier federal competence to regulate the right of assembly. In the course of the federalism reform of 2006, the federal government transferred this competence to the federal states. As a result, some states passed their own assembly laws, such as Bavaria, Lower Saxony, and Saxony. In the other countries, the right of assembly according to Art. 125a, Paragraph 1, Clause 1 of the Basic Law continues to be largely determined by the Assembly Act of the Federation.

Practically significant interventions in the freedom of assembly are the issuance of conditions, the obligation to register, the prohibition and the dissolution of assemblies.

Restrictions

Since the freedom of assembly is limited to the protection of peaceful gatherings, Section 2 (3) of the Assembly Act prohibits the carrying of weapons and other dangerous objects at a gathering. According to Section 27 (1) of the Assembly Act, this constitutes a criminal offense. It is also punishable to carry weapons against enforcement measures by a holder of sovereign powers contrary to Section 17a (1) of the Assembly Act. For example, masks, body pads and martial arts equipment are constitutive. Furthermore, from § 17a paragraph 2, § 29 paragraph 1 number 1 a VersammlG there is a criminal masking prohibition . According to this, it is forbidden to cover one's face and to carry objects that are suitable and intended to prevent the establishment of identity. For example, balaclavas and masks are not permitted .

Registration requirement

According to Section 14 of the General Assembly Act, the organizer of a meeting is obliged to register it with the competent authority under state law at least 48 hours before the announcement of its implementation . Often this is the regulatory authority .

The obligation to register collides with the express guarantee of Art. 8 Paragraph 1 GG that citizens may assemble at any time without registration or permission. The Federal Constitutional Court and the prevailing view in jurisprudence nevertheless consider § 14 of the General Assembly Act to be constitutional and carry out legal training in the form of a teleological reduction . According to this, spontaneous meetings are exempt from the obligation to register in advance, as prior registration is not possible due to the lack of a coordinating event manager. The 48-hour deadline does not apply to an emergency meeting, as it is in their nature to form within a particularly short period of time, so that a timely registration is usually not possible. The Federal Constitutional Court also considers the criminality of holding an unannounced meeting, which results from Section 26 of the General Assembly Act, to be constitutional because of the teleological reduction in Section 14 of the General Assembly Act.

Some legal scholars accuse the prevailing view of the handling of Section 14 of the General Assembly Act as exceeding the limits of interpretation: The wording of Section 14 of the General Assembly Act is too clear to allow for further legal training. Therefore, this is methodologically inadmissible, so that the norm must be assessed as unconstitutional.

Prohibition of assembly and the imposition of a condition or restriction

The right to prohibit an open-air meeting arises from Section 15 (1) of the General Assembly Act. According to this, the competent authority may prohibit a meeting or make it dependent on certain conditions or restrictions if, according to the circumstances recognizable at the time the order was issued, public safety or order is directly endangered when the meeting is held. There is a danger if, if things continue unhindered, there is a risk of damage to a protected item in the foreseeable future.

The public security interest includes the integrity of the legal system and individual legal interests as well as the functionality of public institutions. There is a danger, for example, if a meeting threatens to damage the body and property of third parties. The threat of committing criminal offenses, such as sedition ( Section 130 of the Criminal Code), is also a danger.

Public order as a protected asset encompasses all unwritten rules for the conduct of individuals in public, the observance of which is generally regarded as an indispensable prerequisite for a prosperous coexistence. What is disputed in jurisprudence is under what condition the endangerment of this legal interest is sufficient to proceed against a meeting. This issue is of great practical importance for the prohibition of right-wing extremist gatherings where sedition or other criminal offenses are not expected. In the absence of imminent criminal offenses, there was no danger to public safety. Therefore, authorities regularly based bans on a violation of public order. They argued that the purpose of these gatherings violated common decency. This assessment collided with the freedom of assembly and freedom of expression, since the allegation of violation of public order was directed against the thematic content of the assembly. The Federal Constitutional Court decided in several rulings that a threat to the extremely indeterminate legal interest of public order is usually not enough to restrict the freedom of assembly. As a result, the legislature created two new legal norms: Pursuant to Section 15 (2) VersammlG, assemblies may be banned that commemorate the victims of treatment under the National Socialist tyranny and arbitrary rule at a memorial of historical importance, which is determined as such by state law. This assumes that, according to the circumstances ascertainable at the time the order was issued, there are concerns that the dignity of the victims will be impaired by the gathering or the elevator.

The prohibition of a meeting is a serious interference with the freedom of assembly. Therefore, it is usually only proportionate if the acting authority has no other means of averting the danger. Government officials are therefore required to intervene with less intensity as far as possible. According to Section 15 (1) of the General Assembly Act, the authority can, in particular, make the holding of a meeting dependent on the fulfillment of a condition. This is an additional regulation, for example the obligation to use files or the recording of personal details.

Dissolution of a meeting

Section 15 (3) of the Assembly Act empowers the police to dissolve an ongoing gathering in the open air. The prerequisite for this is that the meeting is not registered, that it deviates from the details given in the registration, that it violates a condition or that the conditions for a ban are met. The fact that the breach of the notification requirement is sufficient for dissolution is generally viewed as disproportionate. Therefore, the prevailing view in jurisprudence interprets the norm in this regard in conformity with the constitution: A dissolution due to a breach of the notification obligation also requires that the meeting poses a concrete risk to an important legal assetdue to the failure to register. Failure to register for spontaneous and urgent meetings does not allow cancellation. If a prohibited meeting takes place, it must be dissolved in accordance with Section 15 (4) General Assembly Act.

As a result of a dissolution, the meeting participants are obliged to immediately move away from the meeting place. With the dissolution, the protection of the Assembly Act ends in terms of time, so that general police law is fully applicable again. For example, the obligation to remove can be enforced by issuing and enforcing a dismissal or detention .

According to the prevailing opinion in jurisprudence, Section 15 (3) of the General Assembly also authorizes the taking of other measures that are milder than dissolution. As such, the seizure of banners and bannerscomesinto question. This view argues that under the conditions that justify the dissolution of an assembly, the milder measures are all the more permissible.

Further measures

According to Section 18 (3) of the General Assembly Act, the police may exclude participants from a gathering who grossly disrupt order. Furthermore, according to § 19a VersammlG , authorities are allowed to make picture and sound recordings of meeting participants at or in connection with meetings. This poses a significant threat to public safety or order.

Art. 17a GG

Article 17a of the Basic Law contains a further legal reservation . According to this, the freedom of assembly may be restricted by laws on military service and alternative service for members of the armed forces and alternative service. A corresponding regulation contains, for example, Section 15 (3) of the Soldiers Act , which prohibits soldiers from participating in political events in uniform.

Constitutional barriers

Assemblies that do not take place in the open air are not subject to any legal reservation , with the exception of Article 17a of the Basic Law. However, the Federal Constitutional Court also recognizes the possibility of statutory restrictions for such assemblies. This can result from constitutional law that conflicts with freedom of assembly. This possibility of restriction is based on the fact that constitutional provisions, as rights of equal rank, do not displace one another, but are brought into a relationship of practical concordance in the event of a collision . This requires a balance between the freedom of assembly and the colliding good. The aim is to create a balance that is as gentle as possible and that gives every constitutional good as far-reaching validity as possible. An encroachment on the freedom of assembly based on the violation of a constitutional good also requires legal specification.

Intervention in an assembly that does not fall under Article 8 paragraph 2 of the Basic Law therefore presupposes that its implementation collides with a property of constitutional status. This comes into consideration, for example, in the event of a direct threat to the physical integrity of persons, which is protected by Art. 2 Paragraph 2 Sentence 1 of the Basic Law. For public gatherings in closed rooms, the Assembly Act contains in § 5 - § 13 VersammlG several provisions that allow interventions in public gatherings in closed rooms to protect constitutional goods. For example, Section 13 (1) No. 2 VersammlG allows the dissolution of a meeting that is violent or rebellious or that poses an immediate risk to the life and health of the participants.

The provisions of the Assembly Act do not apply to closed-door meetings that are not open to the public. However, based on general police law, freedom of assembly may be restricted.

The quotation requirement of Article 19, Paragraph 1, Sentence 2 of the Basic Law does not apply to unreservedly guaranteed fundamental rights such as the freedom of assembly of non-public assemblies.

literature

- Achim Bertuleit: Seated demonstrations between procedurally protected freedom of assembly and coercion based on administrative law . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-08184-4 .

- Hermann-Josef Blanke: Art. 8 . In: Klaus Stern, Florian Becker (Ed.): Basic rights - Commentary The basic rights of the Basic Law with their European references . 2nd Edition. Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-452-28265-1 .

- Otto Depenheuer: Art. 8 . In: Theodor Maunz, Günter Dürig (ed.): Basic Law . 81st edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-45862-0 .

- Christoph Gröpl: Art. 8 . In: Christoph Gröpl, Kay Windthorst, Christian von Coelln (eds.): Basic Law: Study Commentary . 3. Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-64230-2 .

- Christoph Gusy: Art. 8 . In: Hermann von Mangoldt, Friedrich Klein, Christian Starck (eds.): Commentary on the Basic Law. 6th edition. tape 1 . Preamble, Articles 1 to 19. Vahlen, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-8006-3730-0 .

- Wolfgang Hoffmann-Riem: § 106 . In: Detlef Merten, Hans-Jürgen Papier (ed.): Handbook of fundamental rights in Germany and Europe . Volume IV: Fundamental Rights in Germany - Individual Fundamental Rights ICH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-8114-4443-0 .

- Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 . In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- Hans Jarass: Art. 8 . In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Comment . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- Philip Kunig: Art. 8 . In: Ingo von Münch, Philip Kunig (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 6th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-58162-5 .

- Sebastian Müller-Franken: Art. 8 . In: Bruno Schmidt-Bleibtreu, Hans Hofmann, Hans-Günter Henneke (eds.): Commentary on the Basic Law: GG . 13th edition. Carl Heymanns, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-452-28045-9 .

- Helmuth Schulze-Fielitz: Art. 8 . In: Horst Dreier (Ed.): Basic Law Comment: GG . 3. Edition. Volume I: Preamble, Articles 1-19. Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck 2013, ISBN 978-3-16-150493-8 .

- Heinrich Wolff: Art. 8 . In: Dieter Hömig, Heinrich Wolff (Hrsg.): Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Handkommentar . 11th edition. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2016, ISBN 978-3-8487-1441-4 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , Rn. 4. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 124, 300 (320) : Rudolf Heß commemoration. BVerfGE 69, 315 (344) : Brokdorf.

- ↑ BVerfGE 128, 226 : Fraport.

- ↑ Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , Rn. 1-2. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , Rn. 3. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ Michael Kloepfer: Constitutional Law Volume II . 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59527-1 , § 63, Rn. 2.

- ↑ BVerfGE 69, 315 : Brokdorf.

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Preparation before Art. 1 , marginal no. 19-23. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Comment . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 . Friedhelm Hufen: Staatsrecht II: Grundrechte . 5th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-69024-2 , § 6, Rn. 2.

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Preparation before Art. 1 , marginal no. 19-23. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Comment . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 . Friedhelm Hufen: Staatsrecht II: Grundrechte . 5th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-69024-2 , § 6, Rn. 2.

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Art. 8 , Rn. 11. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Commentary . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ↑ Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , Rn. 50. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ^ Thomas Mann, Esther-Maria Worthmann: Occupational freedom (Art. 12 GG) - structures and problem constellations . In: Juristische Schulung 2013, p. 385 (386).

- ↑ Sebastian Müller-Franken: Art. 8 , Rn. 50. In: Bruno Schmidt-Bleibtreu, Hans Hofmann, Hans-Günter Henneke (eds.): Commentary on the Basic Law: GG . 13th edition. Carl Heymanns, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-452-28045-9 .

- ↑ Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , Rn. 52. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ Article 26 of the Berlin Constitution: "All men and women have the right to assemble peacefully and unarmed for purposes permitted by law."

- ↑ Article 23 of the constitution of the state of Brandenburg: "All people have the right to assemble peacefully and unarmed without registration or permission."

- ↑ Article 14 of the Constitution of the State of Hesse: "All Germans have the right to assemble peacefully and unarmed without registration or special permission."

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of July 12, 2001, 1 BvQ 28/01, 1 BvQ 30/01 = NJW 2001, p. 2459.BVerfG, decision of October 26, 2004, 1 BvR 1726/01 = NVwZ 2005, p. 80 .

- ^ Volker Epping: Basic rights . 8th edition. Springer, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-662-58888-8 , Rn. 32. Otto Depenheuer: Art. 8 , marginal no. 44. In: Theodor Maunz, Günter Dürig (ed.): Basic Law . 81st edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-45862-0 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 104, 92 : Sit-In Blockades III.

- ↑ BVerfGE 69, 315 (343) : Brokdorf.

- ↑ Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , Rn. 14. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of July 12, 2001, 1 BvQ 28/01, 1 BvQ 30/01 = NJW 2001, p. 2459.

- ↑ Christoph Möllers: Change of fundamental rights judicature. An analysis of the case law of the First Senate of the BVerfG , in: NJW 2005, p. 1973.

- ↑ BVerfGE 128, 226 (250) : Fraport.

- ↑ Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , Rn. 15-16. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 . Christoph Gusy: Art. 8 , Rn. 17-18. In: Hermann von Mangoldt, Friedrich Klein, Christian Starck (eds.): Commentary on the Basic Law. 6th edition. tape 1 . Preamble, Articles 1 to 19. Vahlen, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-8006-3730-0 .

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of the 3rd Chamber of the First Senate of June 20, 2014: 1 BvR 980/13 , Rn. 17th

- ↑ Michael Kloepfer: Constitutional Law Volume II . 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59527-1 , § 63, Rn. 12.

- ↑ Sebastian Müller-Franken: Art. 8 , Rn. 49. In: Bruno Schmidt-Bleibtreu, Hans Hofmann, Hans-Günter Henneke (eds.): Commentary on the Basic Law: GG . 13th edition. Carl Heymanns, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-452-28045-9 .

- ↑ Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , Rn. 29-30. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ a b BVerfGE 104, 92 (106) : Sit Blockades III.

- ↑ BVerfGE 73, 206 (248) : Sit Blockades I.

- ↑ a b Hans Jarass: Art. 8 , Rn. 9. Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: comment . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ^ Wilhelm Schluckebier: § 240 , Rn. 20. In: Helmut Satzger, Wilhelm Schluckebier, Gunter Widmaier (ed.): Criminal Code: Commentary . 3. Edition. Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-452-28685-7 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 73, 206 (249) : Sit-In Blockades I. BVerfGE 87, 399 (406) : Dissolution of the Assembly.

- ↑ Philip Kunig: Art. 8 , Rn. 23. In: Ingo von Münch, Philip Kunig (Ed.): Basic Law: Commentary . 6th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-58162-5 . Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , marginal no. 32. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ Achim Bertuleit: Seated demonstrations between procedurally protected freedom of assembly and coercion based on administrative law . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1994, ISBN 978-3-428-08184-4 , pp. 82 f .

- ↑ BVerfGE 69, 315 (361) : Brokdorf.

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Art. 8 , Rn. 10. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Commentary . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 69, 315 (360) : Brokdorf.

- ↑ VG Minden, judgment of May 3, 1983, 4 K 120/82 = NVwZ 1984, p. 331.

- ↑ BVerfGE 69, 315 (349) : Brokdorf.

- ↑ BVerfGE 69, 315 (343) : Brokdorf. BVerfGE 87, 399 (406) : resolution of the meeting.

- ↑ OVG Berlin-Brandenburg, judgment of November 18, 2008, 1 B 2.07 = NVwZ-RR 2009, p. 370.

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Art. 8 , Rn. 5-6. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Comment . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ↑ BVerwGE 91, 135 .

- ↑ Moritz Hartmann: Protest camps as assemblies within the meaning of Art. 8 I Basic Law? In: NVwZ 2018, p. 200.

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of the 3rd Chamber of the First Senate of June 20, 2014: 1 BvR 980/13 . Marg. 16, 18f.

- ↑ BVerfGE 84, 203 (209) : Republicans.

- ↑ Stefan Muckel: Comment on OVG NRW, decision of July 29, 2016, 15 B 876/16 . In: Legal worksheets 2017, p. 396.

- ↑ Michael Kloepfer: Constitutional Law Volume II . 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59527-1 , § 63, Rn. 68.

- ↑ BVerfGE 81, 236 (258) .

- ^ Lothar Michael, Martin Morlok: Grundrechte . 6th edition. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2017, ISBN 978-3-8487-3871-7 , Rn. 264.

- ↑ Michael Kloepfer: Constitutional Law Volume II . 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59527-1 , § 63, Rn. 69.

- ^ Michael Sachs: Constitutional Law II - Basic Rights . 3. Edition. Springer, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-662-50363-8 , Chapter 8, Rn. 1.

- ↑ Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , Rn. 56. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ Gerrit Manssen: Staatsrecht II: Grundrechte . 13th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-68979-6 , Rn. 504. Michael Kloepfer: Constitutional Law Volume II . 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59527-1 , § 63, Rn. 46.

- ↑ Michael Kloepfer: Constitutional Law Volume II . 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59527-1 , § 63, Rn. 46.

- ↑ Michael Kloepfer: Constitutional Law Volume II . 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59527-1 , § 63, Rn. 60.

- ↑ Christoph Gröpl: Art. 8 , Rn. 27. In: Christoph Gröpl, Kay Windthorst, Christian von Coelln (eds.): Basic Law: Study Commentary . 3. Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-64230-2 .

- ↑ a b BVerfGE 128, 226 (255) : Fraport.

- ↑ Hans Jarass: Art. 8 , Rn. 17. In: Hans Jarass, Bodo Pieroth: Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany: Commentary . 28th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66119-8 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Hoffmann-Riem: § 106 , Rn. 104. In: Detlef Merten, Hans-Jürgen Papier (ed.): Handbook of fundamental rights in Germany and Europe . Volume IV: Fundamental Rights in Germany - Individual Fundamental Rights ICH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-8114-4443-0 . Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , marginal no. 61. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Commentary . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 120, 274 (343) : Online searches.

- ↑ Wolfgang Hoffmann-Riem: § 106 , Rn. 101. In: Detlef Merten, Hans-Jürgen Papier (ed.): Handbook of fundamental rights in Germany and Europe . Volume IV: Fundamental Rights in Germany - Individual Fundamental Rights ICH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-8114-4443-0 . Judith Froese: The interaction between freedom of assembly and the law of assembly . In: Juristische Arbeitsblätter 2015, p. 679.

- ↑ Matthias Kötter, Jakob Nolte: What remains of the “Police Resistance of the Right of Assembly”? In: Public Administration 2009, p. 399.

- ^ Christian von Coelln: The restricted police strength of non-public meetings . In: NVwZ 2001, p. 1234.

- ↑ Kathrin Bünnigmann: Police Resistance in Assembly Law . In: Juristische Schulung 2016, p. 695. Johannes Deger: Police measures at assemblies? In: NVwZ 1999, p. 265 (266).

- ↑ Florian von Alemann, Fabian Scheffczyk: Current questions of the freedom of design of assemblies . In: Legal worksheets 2013, p. 407.

- ↑ Volkhard Wache: § 17a VersammlG , Rn. 3. In: Georg Erbst, Max Kohlhaas (ed.): Criminal law subsidiary laws . 217. Supplementary delivery edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-37751-8 .

- ↑ Volkhard Wache: § 17a VersammlG , Rn. 6-8. In: Georg Erbst, Max Kohlhaas (Ed.): Criminal law subsidiary laws . 217. Supplementary delivery edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-37751-8 .

- ↑ a b c Christoph Gröpl: Art. 8 , Rn. 36. In: Christoph Gröpl, Kay Windthorst, Christian von Coelln (eds.): Basic Law: Study Commentary . 3. Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-64230-2 .

- ↑ Helmuth Schulze-Fielitz: Art. 8 , Rn. 83. In: Horst Dreier (Ed.): Basic Law Comment: GG . 3. Edition. Volume I: Preamble, Articles 1-19. Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck 2013, ISBN 978-3-16-150493-8 .

- ↑ a b Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , Rn. 64. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ^ Volker Epping: Basic rights . 8th edition. Springer, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-662-58888-8 , Rn. 68.

- ↑ Thorsten Kingreen, Ralf Poscher: Police and regulatory law: with the right of assembly . 10th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-406-72956-0 , § 8, Rn. 2.

- ↑ Ulrike Lembke: Basic cases to Art. 8 GG . In: Juristische Schulung 2005, p. 1081 (1081-1082).

- ↑ Hannes Beyerbach: Extreme right-wing gatherings - (also) a dogmatic challenge . In: Juristische Arbeitsblätter 2015, p. 881 (883).

- ↑ Thorsten Kingreen, Ralf Poscher: Police and regulatory law: with the right of assembly . 10th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-406-72956-0 , § 8, Rn. 46.

- ^ Christoph Gusy: Right-wing extremist assemblies as a challenge to legal policy . In: JuristenZeitung 2002, p. 105. Hannes Beyerbach: Right-wing extremist assemblies - (also) a dogmatic challenge . In: Juristische Arbeitsblätter 2015, p. 881 (883).

- ↑ BVerfGE 69, 315 (353) : Brokdorf. BVerfG, decision of January 27, 2012, 1 BvQ 4/12 = NVwZ 2012, p. 749.

- ↑ Ulrike Lembke: Basic cases to Art. 8 GG . In: Juristische Schulung 2005, p. 1081 (1083).

- ↑ BVerfGK 6, 104 .

- ↑ Klaus Stohrer: The fight against right-wing extremist assemblies through the new § 15 paragraph II VersG . In: Legal Training 2006, p. 15.

- ↑ Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , Rn. 62. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ Otto Depenheuer: Art. 8 , Rn. 137. In: Theodor Maunz, Günter Dürig (Ed.): Basic Law . 81st edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-45862-0 .

- ↑ Markus Thiel: Police and regulatory law . 4th edition. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2019, ISBN 978-3-8487-4876-1 , § 19, marginal no. 10.

- ↑ BVerfGE 69, 315 (350) : Brokdorf.

- ↑ Volkhard Wache: § 15 VersammlG , Rn. 15. In: Georg Erbst, Max Kohlhaas (ed.): Criminal law subsidiary laws . 217. Supplementary delivery edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-37751-8 .

- ↑ Markus Thiel: Police and regulatory law . 4th edition. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2019, ISBN 978-3-8487-4876-1 , § 19, marginal no. 11-12.

- ↑ Jürgen Schwabe: Disaster in the right of assembly: Two misleading chamber decisions of the Federal Constitutional Court . In: The Public Administration 2010, p. 720. Matthias Hettich: Displacement and detention after the dissolution of the assembly: Reply to Jürgen Schwabe, DÖV 2010, 720 . In: Public Administration 2010, p. 954.

- ↑ Christoph Gröpl, Isabel, Leinenbach: Exam focus on the law of assembly . In: Legal worksheets 2018, p. 8 (13). Markus Thiel: Police and regulatory law . 4th edition. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2019, ISBN 978-3-8487-4876-1 , § 19, marginal no. 14th

- ↑ Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , Rn. 78. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ Wolfram Höfling: Art. 8 , Rn. 83. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ Tristan Kalenborn: The practical concordance in case processing . In: Juristische Arbeitsblätter 2016, p. 6 (8).

- ↑ Markus Thiel: Police and regulatory law . 4th edition. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2019, ISBN 978-3-8487-4876-1 , § 19, marginal no. 22nd

- ↑ Christoph Gröpl: Art. 8 , Rn. 33. In: Christoph Gröpl, Kay Windthorst, Christian von Coelln (eds.): Basic Law: Study Commentary . 3. Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-64230-2 .